by Matteo Pirola

in collaboration with Annalisa Ubaldi for archival research

To speak of museums is to speak of culture, because museums are those architectures that contain and preserve, promote and disseminate the “facts” of the natural, scientific and artistic history of mankind, through which individuals can learn, develop and progress. Each museum is built around a collection, a set of “documents” with which one surrounds oneself in order to give permanence to individual or social life.

In the pages of Domus, museums offer countless opportunities for presentation and debate, with exemplary projects and critical essays outlining their evolution over the last century of history. We have selected, reviewed, rewritten and organised 50 exemplary cases published by the magazine and available in the digital archive, ranging from fundamental projects of modern architecture to the most emblematic cases of the Italian school that opened a new path in international museography in the 1950s. Exceptional cases include design and architecture museums, where content and container often merge seamlessly into a total work of art. Unique are the museums dedicated to a single artist or collector, or those linked to art foundations that innovate in the methods of research and cultural communication of experimental content. Finally, there are the new iconic and symbolic museums, which, especially since the 1990s, have begun to systematically transform city centres and suburbs with attractive and evocative places that have a strong regenerative effect.

These selected examples illustrate some of the design characteristics that influence the interpretation of museum architecture. After the birth of a new isolated building, the theme of renovation and extension often arises. Museums are sometimes isolated, sometimes grouped together in a system that integrates parts of the city, and since the 1970s the mode of public competition has become the standard for selecting the best project to be realised.

Often these architectures are debut works, inaugurating young architects who, by virtue of their public scope and expressiveness, become recognisable and reference points. Light, especially natural light, is a constant theme that, in the best cases, has shaped the architecture for optimal enjoyment of the works, while the flow of the itinerary is another very important variable in the design of an exhibition space.Museums are therefore essentially “exhibition machines”, in which the activity of exhibiting is primary and in which, together with the architecture (permanent), the development of the exhibition (temporary) is fundamental.

One of the increasingly relevant issues to be considered in the interpretation of a museum, which contains history but is also a contemporary tool aimed at future generations, is the cultural mission and therefore the educational function of museums.

One of the increasingly relevant issues to be considered in the interpretation of a museum, which contains history but is also a contemporary tool aimed at future generations, is - as Gillo Dorfles already announced in Domus in 1955 - the cultural mission and therefore the educational function of museums, which must never be just a collection of documents or “artistic fossils”, nor a static and dusty display of past masterpieces. The museum should always be a living organism, like a dynamic cultural means of “actively influencing society”, like a “human nursery”, ideally populated by young people (from childhood) and a “secular” adult public, who attend (and therefore return) after lectures, debates and visits to collections and, above all, to new exhibitions dealing with the present. A museum is therefore a privileged place, a temple of worship and culture, where the social function of art is activated for the community, which, stimulated by artistic and scientific testimonies, reflects towards a common awareness of action in its own time.

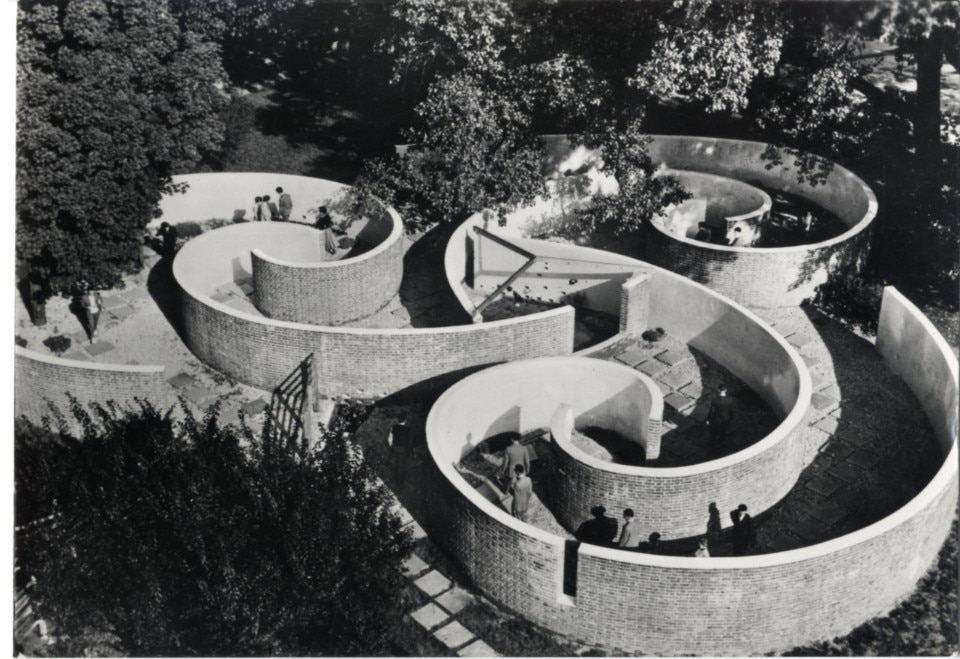

01

Triennale Milano

Milan, Italy, 1933

Domus 56, August 1932

View gallery

View gallery

Palazzo dell'Arte, Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Gianluca di Ioia © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

VI Triennale. Events and concerts in Parco Sempione

Photo Crimella

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

XIII Triennale (1964). Peppo Brivio, Vittorio Gregotti, Lodovico Meneghetti and Giorgio Stoppino, Kaleidoscope

Photo S.r.l. Ancillotti Fotografie

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Giorgio De Chirico’s Mysterious Baths in the Garden of the Milan Triennale (1973)

Courtesy © Triennale Milano - Archivi

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

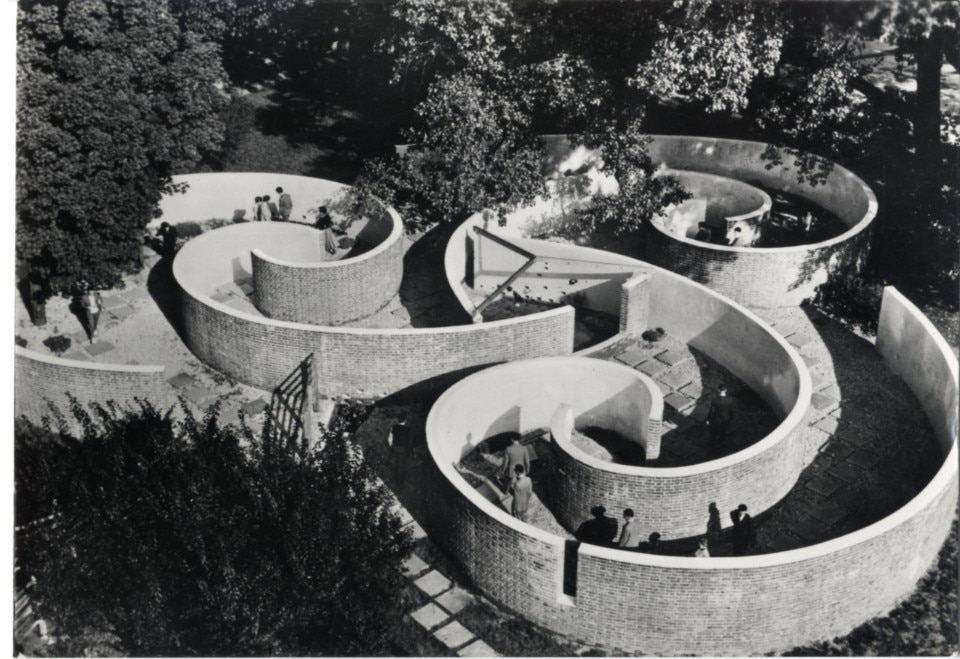

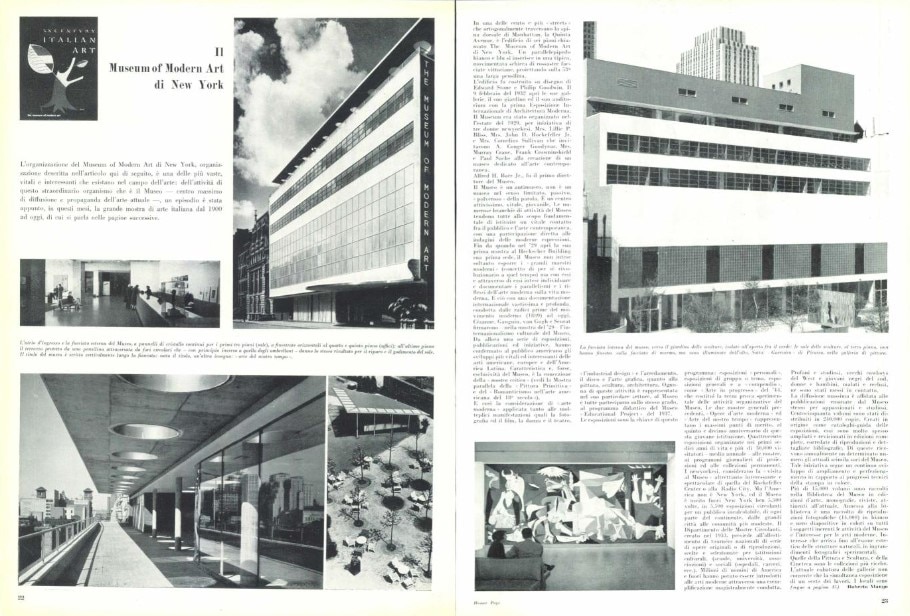

X Triennale (1954). Aerial view of the Children’s Labyrinth designed by B.B.P.R. and built in Parco Sempione for the X Triennale

Photo Fotogramma

Palazzo dell'Arte, Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Gianluca di Ioia © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani-DSL Studio © Triennale Milano

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

VI Triennale. Events and concerts in Parco Sempione

Photo Crimella

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

XIII Triennale (1964). Peppo Brivio, Vittorio Gregotti, Lodovico Meneghetti and Giorgio Stoppino, Kaleidoscope

Photo S.r.l. Ancillotti Fotografie

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

Giorgio De Chirico’s Mysterious Baths in the Garden of the Milan Triennale (1973)

Courtesy © Triennale Milano - Archivi

Triennale Milano, Italy, 1933

X Triennale (1954). Aerial view of the Children’s Labyrinth designed by B.B.P.R. and built in Parco Sempione for the X Triennale

Photo Fotogramma

Today, it is simply known as Triennale Milano, owing to the international exhibitions held every three years, which were the original purpose of this institution established in the early 1920s. However, the architecture once had a more significant and valuable name: Palazzo dell’Arte (at the Park). Here, “art” encompasses all aspects of human creativity, ingenuity, design, and beauty, spanning from design to architecture, and from visual and applied arts to stage and performance arts. The Museum, designed by Giovanni Muzio, is an original and extraordinary architectural work, an emblematic and innovative example admired throughout the world. It served as a cornerstone of Italian modernism, giving rise to an entire culture of design, nurturing its inception and evolution. The solitary architecture, characterized by a rounded arch reminiscent of an ark of art, boasts a compact yet dynamic morphology, at once monumental and organic. Inside, the museum offers diverse, modular, and flexible spaces tailored to accommodate various forms of artistic expression. The park is the primary site and raison d’être of the architecture: from the outset, the vision was to create, even before physical structures, works that would defy containment within any structure, no matter how vast, beautiful, or functional. Thus, even amidst nature, visitors could immerse themselves in art and architecture.

- Project:

- Giovanni Muzio

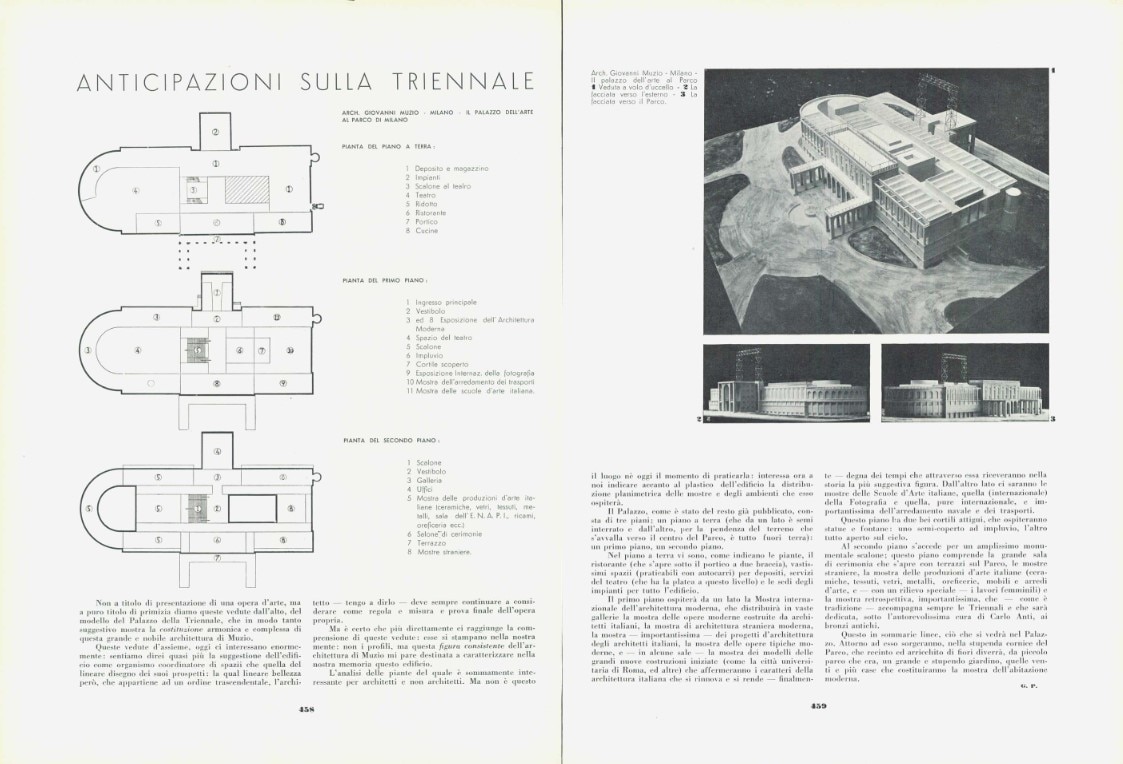

02

Museum of Modern Art (MoMa)

New York, USA, 1939

Domus 241, December 1949

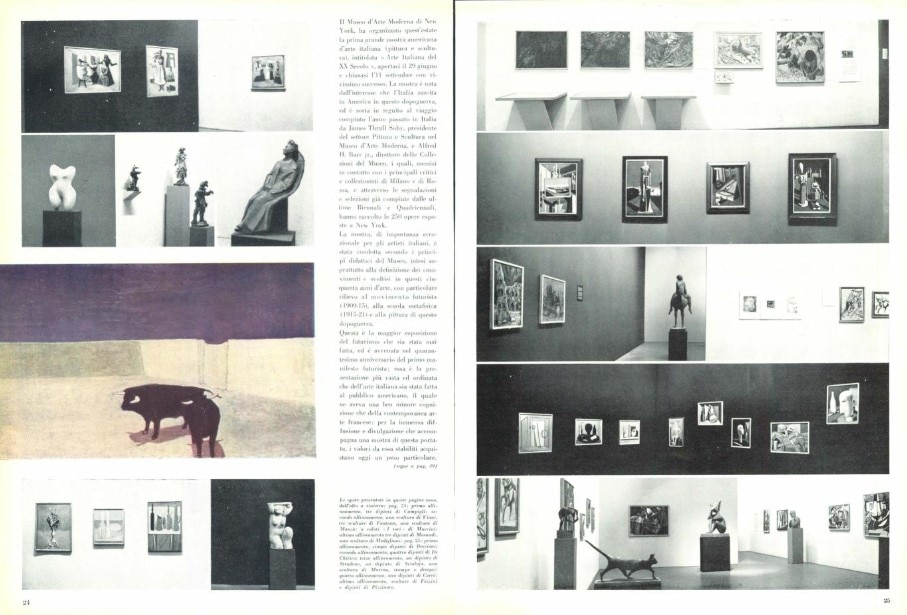

It stands as “the” Museum of Modern Art, conceived in the late 1920s by three visionary women: philanthropists and patrons Lillie Plummer Bliss, Mary Quinn Sullivan, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Its inception coincided with the rise of so-called modern art and reflected the emergence of a modern society that saw New York as a beacon of progress in all fields.

For a decade, the museum organized exhibitions in rented spaces until 1939, when it found a permanent home. Designed by Edward Durell Stone and Philip Goodwin, the building has remained part of an evolving community that has expanded throughout the century (and into the new millennium with a redesign by Yoshio Taniguchi), aiming to respond to evolving spatial needs while avoiding iconic or monumental tendencies.

Within this modern museum concept, art found expression in various new and diverse forms, including architecture (notable exhibitions include those dedicated to International Style in 1932 and the first Bauhaus exhibition in 1938), industrial design, photography, theater, as well as traditional media such as painting, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture. The museum’s original concept of providing a “proving ground for works” in direct relation to the public was evident in the outdoor display of artworks in a dedicated garden. This ethos extended to the pioneering approach of hosting “critical”, thematic, and comparative exhibitions of modern masters, as well as initiatives such as a “Department of Circulating Exhibitions”, a platform for publications, and a “Public Art Center”, where both children and citizens could engage in artistic creation.

- Project:

- Philip L. Goodwin, Edward Durell Stone

- Project of the Sculpture Garden:

- John McAndre, Alfred H. Barr Junior

- Renovation:

- Yoshio Taniguchi

- Extension:

- Diller Scofidio + Renfro e Gensler

03

Guggenheim Museum

New York, USA, 1959

Domus 671, April 1986

View gallery

View gallery

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Guggenheim Museum New York, USA, 1959

Foto David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

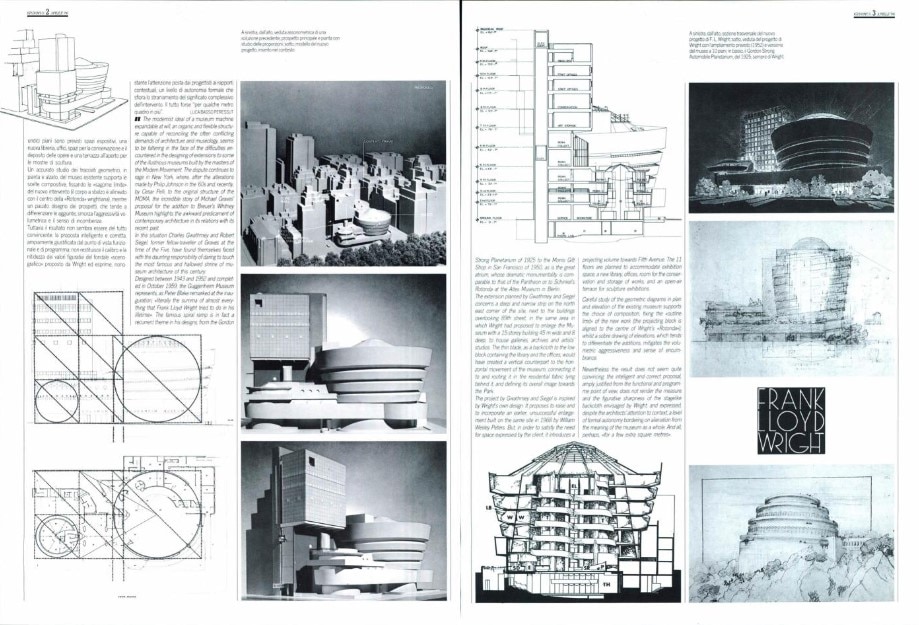

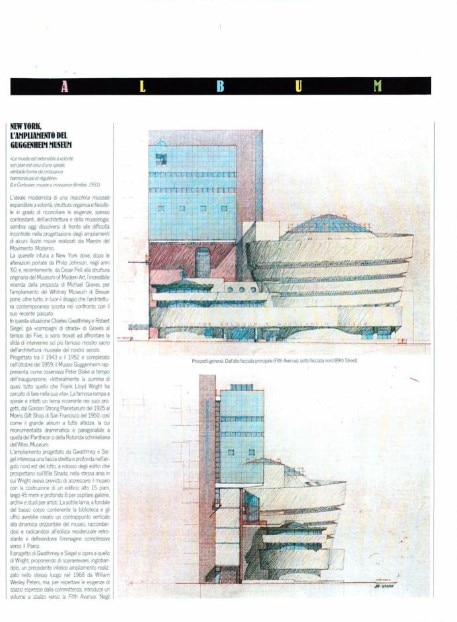

The only museum episode within Frank Lloyd Wright’s extensive body of work, this public masterpiece was completed posthumously after a long and tumultuous journey that began in 1943. This journey was intimately tied to its original and groundbreaking morphology, which served as a manifesto for Wright’s concept of “organic architecture”, nestled in the heart of the vertical city and overlooking its central green lung. The primary innovation was the museum’s sectional design, which took visitors directly up by elevator before gently guiding them down a spiral ramp. Along the way, they could admire artwork adorning the walls or look out over the interior void to a small central “square” illuminated by a large dome. Discussions of the impact of the architecture, which often overshadowed its content, as well as its functionality – questioned by the challenge of effectively displaying paintings on curved and sloping walls – enlivened both American and international artistic and architectural discourse. These debates underscored the complex yet extraordinary relationship between architect and client. In the mid-1980s, the museum underwent an expansion and integration on a small site that had been earmarked for growth since its original conception: amidst various postmodern proposals by Gwathmey & Siegel, the final iteration provided Wright’s iconic “rotunda” with an abstract backdrop, housing a service building with offices and additional exhibition galleries.

- Project:

- Frank Lloyd Wright

04

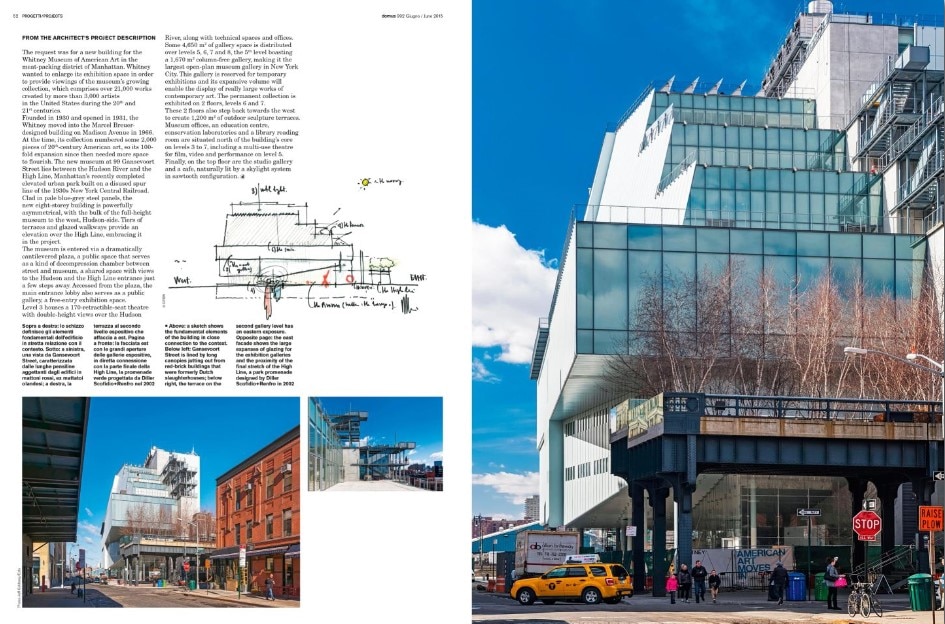

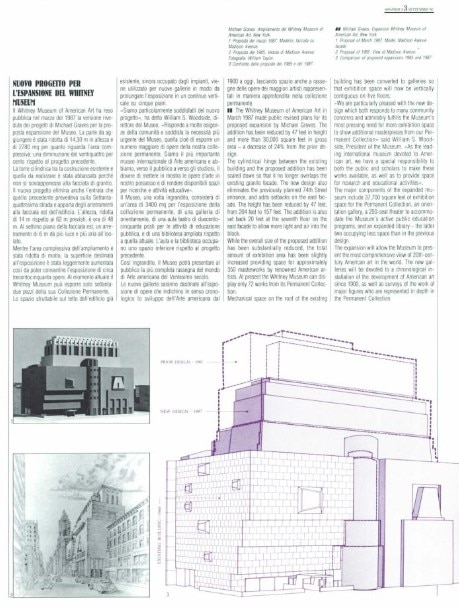

The Whitney Museum of American Art

New York, USA, 1966

Domus 632, October 1982

In the 1930s, the Whitney Museum emerged as New York’s third major center for modern art, alongside the MoMA and the Guggenheim. Founded by the visionary patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, it focused specifically on American-born artists. Marcel Breuer’s design for housing the museum’s initial collection of several thousand works, amassed over three decades, was nothing short of radical. His creation took the form of a large, inverted ziggurat, characterized by vast orthogonal spaces bathed in artificial and zenithal light. “Cubist” openings punctuated the structure to allow natural light to enter, with multiple openings distributed across the north side and a single iconic XL version adorning the main facade. Beneath this imposing mass, at street level, a sculptural, light cantilevered canopy extended over a suspension bridge leading to the entrance foyer and traversing the sculpture garden. The concept for the expansion began to take shape in the 1980s, after proposals by Graves and OMA were rejected. Finally, a change of location was decided upon and Renzo Piano was entrusted with the task. In 2015, the museum’s entire collection, numbering tens of thousands of works, found a new home in a building characterized by its anti-monumental and functional design. This new structure, articulated and permeable, was conceived as a “great factory” for art, a “social condenser” located in a burgeoning cultural and former industrial district.

- Project:

- Renzo Piano

05

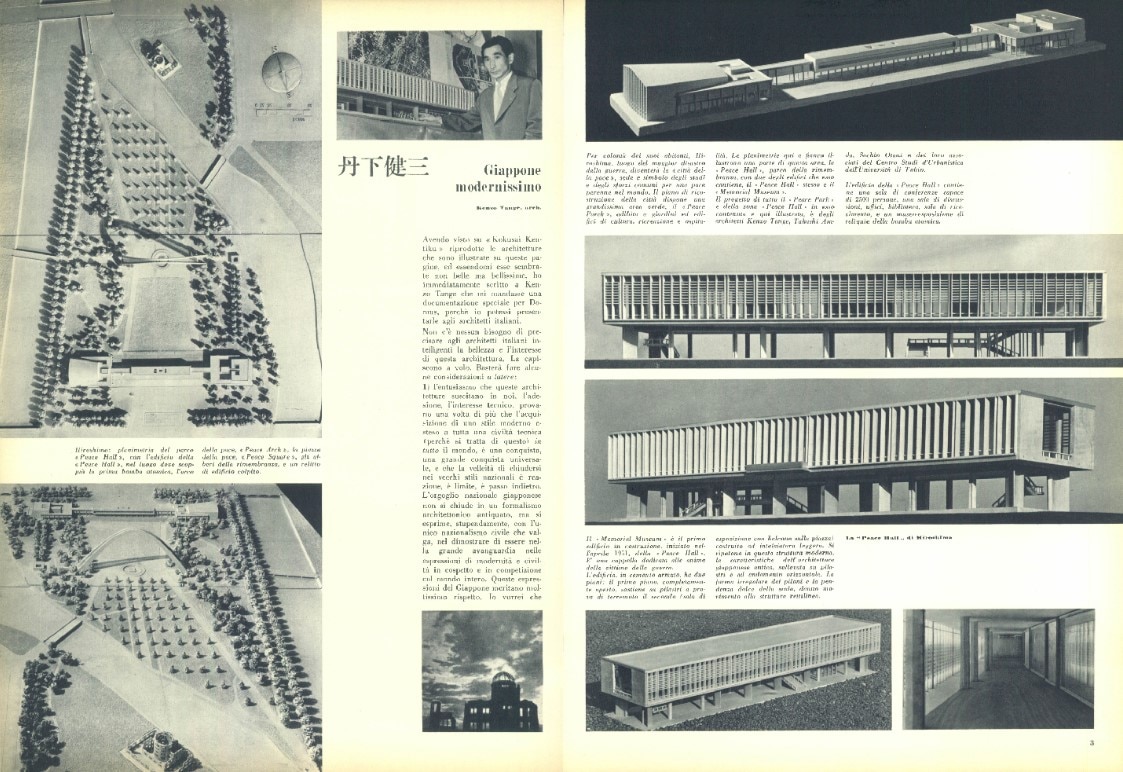

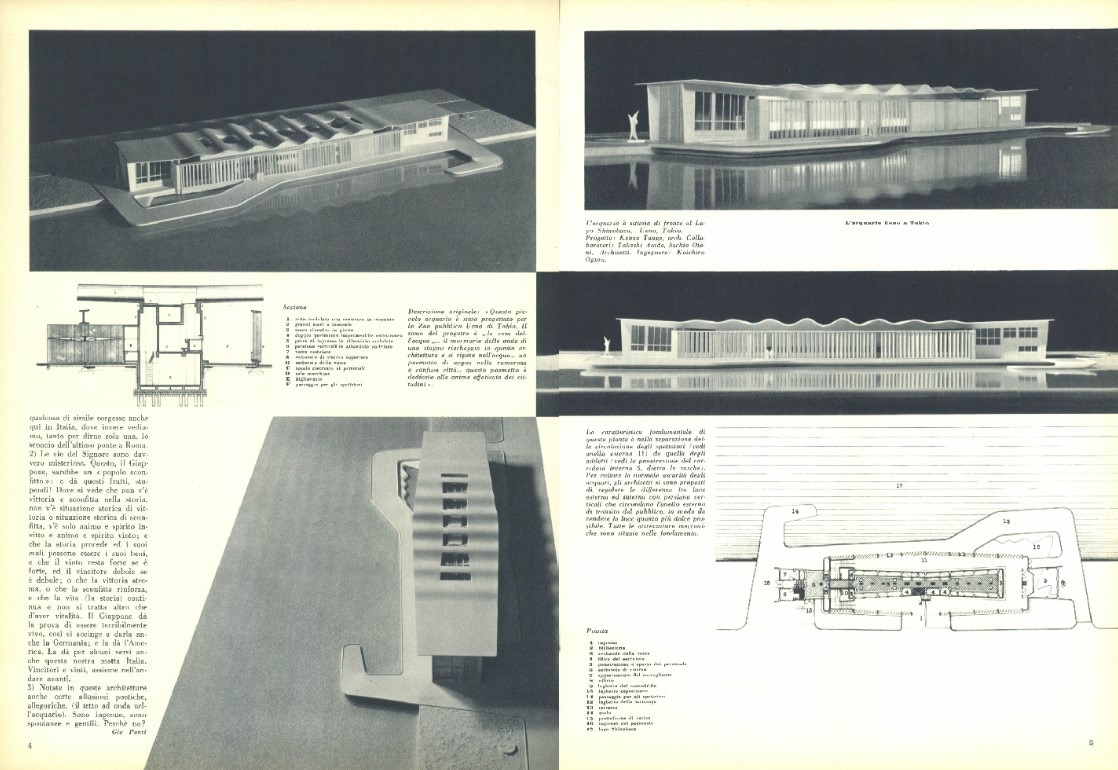

Peace Memorial Museum

Hiroshima, Japan, 1955

Domus 269, April 1952

Kenzo Tange’s first feature in Domus is also a bold statement of intent by its director, Gio Ponti. Attuned to the emergence of a new generation of Japanese architects in the postwar era, armed with a fresh, clear, and universally understandable architectural language, Ponti decided to present the project of a peace museum under construction on the very site where the atomic bombs ended World War II. In response to the devastation wrought by the atomic bombs, Japan embarked on the creation of a public and urban memorial incorporating various architectural elements, including the enduring ruins of the destroyed buildings, with the museum as its centerpiece. The linear architecture, supported by multifaceted columns, fronts onto an expansive park on two sides. Within its walls, it houses artifacts and tells the story of this tragic chapter in history, creating a space that is both “sacred” and secular – “a memorial chapel to the victims of the war”. In the critical analysis articulated in the publication, this project is interpreted as a rejection of nationalist formalisms, embodying instead a flawless celebration of a modern (as Ponti eloquently articulates it, “very modern”) and inherently international style capable of uniting all peoples through the art of architecture.

- Project:

- Kenzō Tange

06

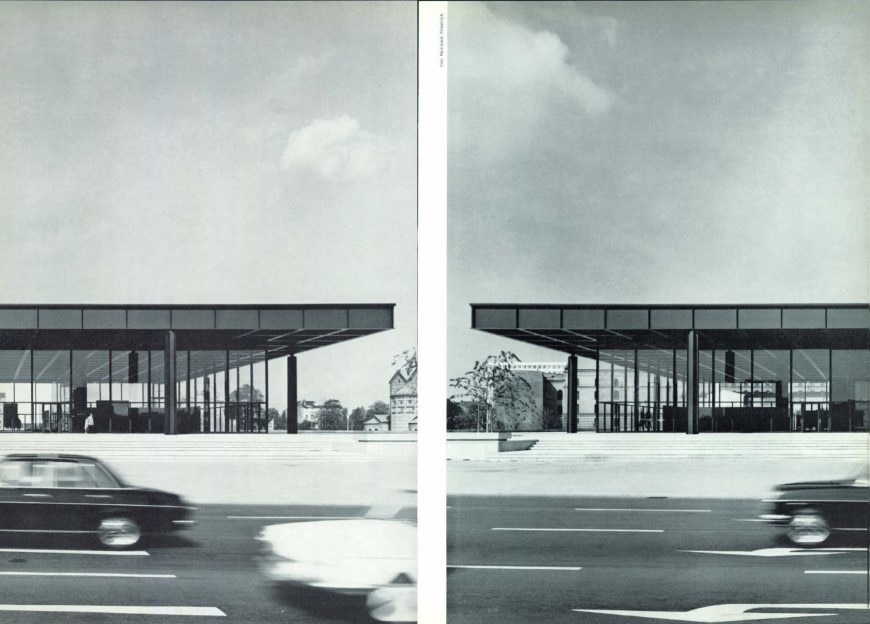

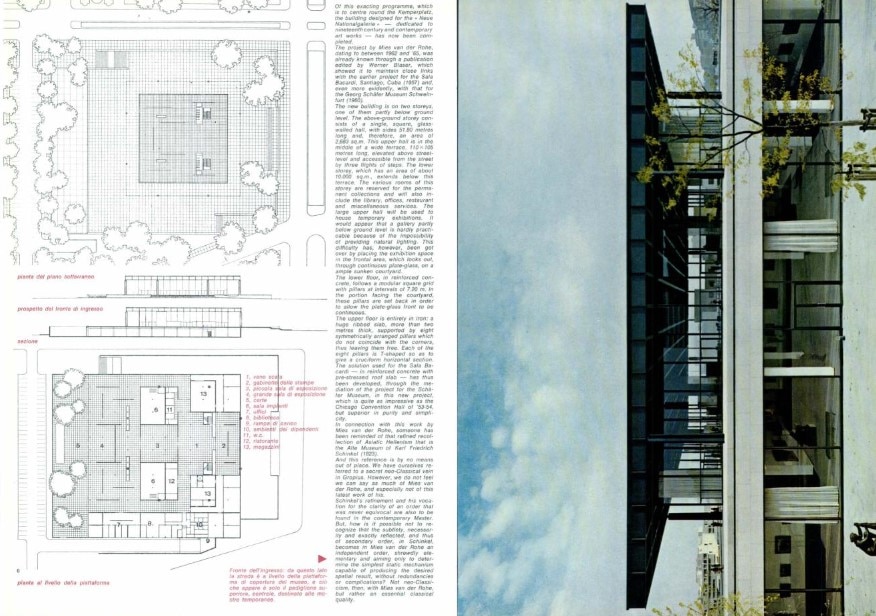

Neue National Galerie

Berlin, Germany, 1968

Domus 478, September 1969

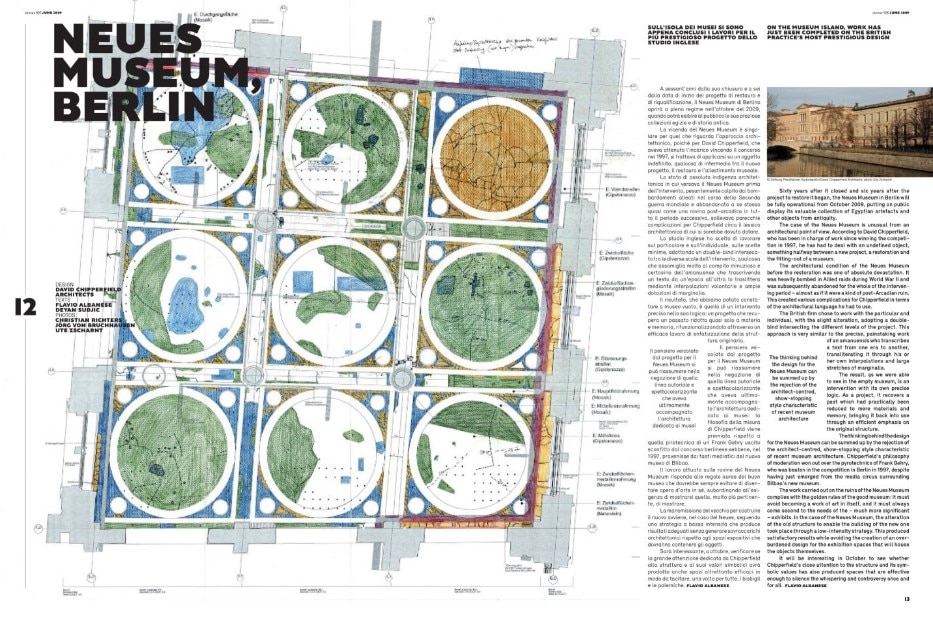

The Neue National Galerie is the crowning achievement of Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, marking his return to his homeland after leaving Germany as the last director of the Bauhaus to begin a legendary new chapter in his career in the United States. Emblematic of his entire architectural ethos, the Gallery embodies a modern architecture of “essential classicism”, paying homage to the neoclassical ideals of Karl Friedrich Schinkel and his Altes Museum, dedicated to ancient art. The Neue National Galerie stands at the heart of a new cultural forum conceived in the aftermath of World War II, in a city ravaged by destruction yet reborn with art in all its forms, including music and literature, with the Berlin Philharmonic and Hans Scharoun’s library. Elevated on a temple-like podium, the gallery houses the permanent collection in a basement container facing an open courtyard, protected by a towering wall. Upstairs, the entrance and temporary exhibitions are housed under a flat, square roof – pure and “ancient” in form, yet constructed of black steel with glazed, transparent curtain walls stretching 50 meters on each side. Eight imposing columns, made of industrial metal sections with a cross-shaped cross-section, punctuate the corners of the structure, leaving the volume unobstructed as they support a substantial slab that seems to float in space. Following a painstaking philological restoration of the modern, led by David Chipperfield Architects, completed in 2021, the museum has been restored to its original splendor, with every detail meticulously attended to.

- Project:

- Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe

- Restoration:

- David Chipperfield Architects

07

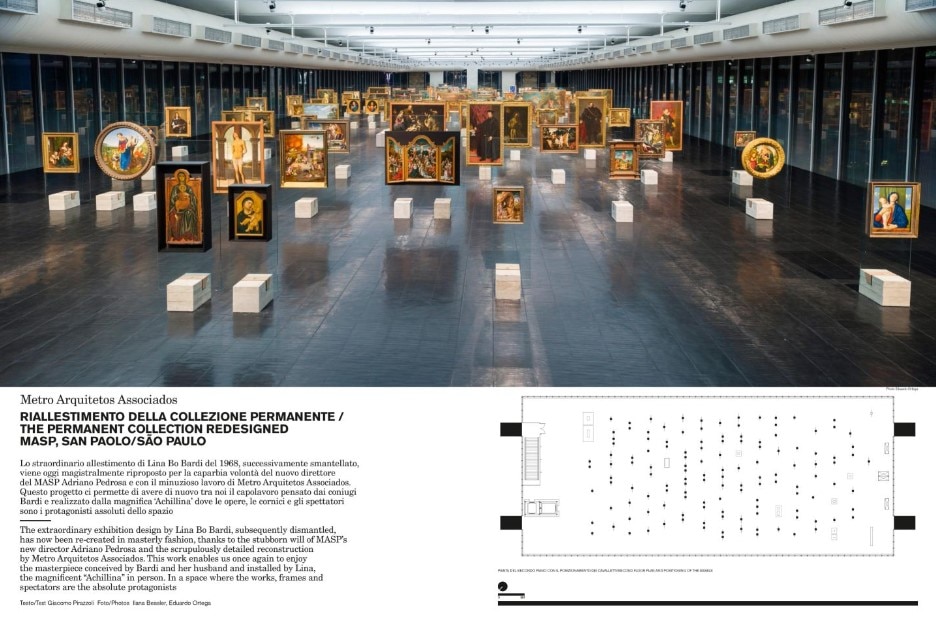

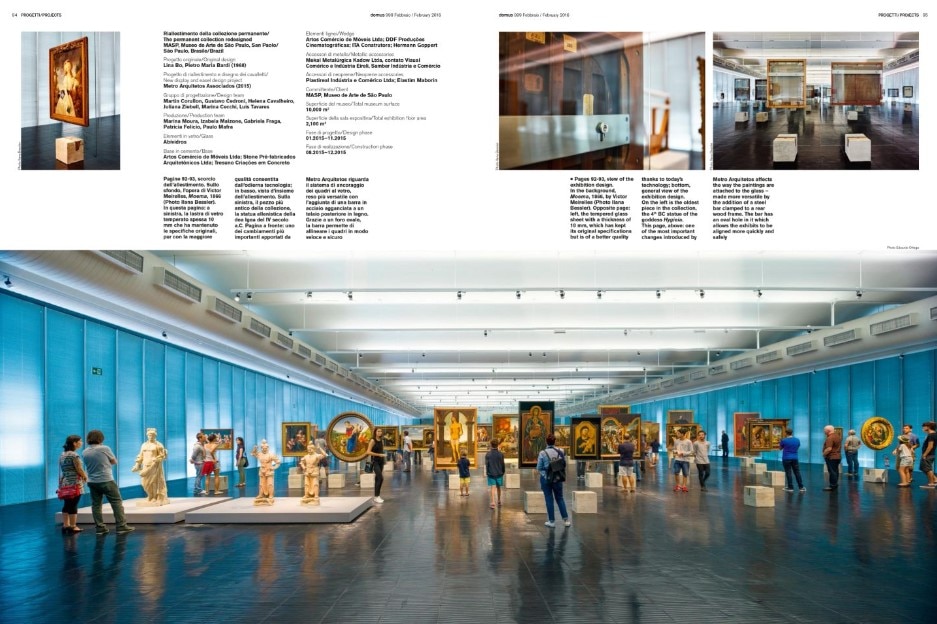

MASP, Museu de Arte de São Paulo

Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1968

Domus 999, February 2016

View gallery

View gallery

Lina Bo Bardi was a true pasionaria of modern architecture – an established and international author, known for being a radical and visionary figure, yet equally attuned to the social imperatives of design as a communal tool. Following the Second World War, she left Italy with her husband, the art critic Pietro Maria Bardi, for Brazil, where they settled, became naturalized citizens, and collaborated in the establishment of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) – the first museum dedicated to modern art and home to the largest collection of European art in South America. The project, spanning approximately a decade, drew upon Bo Bardi’s multifaceted experiences across various Brazilian contexts, resulting in the creation of a distinctive bridge-like structure that embraces an open public space beneath it. Challenging the conventions of traditional museum architecture, Bo Bardi conceived MASP as an “anti-museum”, eschewing static, compartmentalized spaces in favor of a brutalist concrete and glass edifice supported by two bold structural “trestles” painted red. Within this transparent two-story container, the floor plan remains unencumbered by internal obstacles, fostering an uninterrupted flow of movement. Bo Bardi also personally curated the arrangement of works within the museum’s permanent collection. Initially positioned to the sides of the space, the artworks have recently been returned to their original configuration, aligning with Bo Bardi’s vision of offering visitors a liberated, unguided experience – a departure from the traditional linear path, inviting active participation and free exploration.

- Project:

- Lina Bo Bardi

- Extension:

- Júlio Neves studio Metro Arquitetos Associados with Martin Corullon and Gustavo Cedroni

08

Louisiana Museum

Humlebæk, Denmark, 1958

Domus, February 2024

View gallery

View gallery

Situated in a picturesque park, the Louisiana Museum consists of an old neoclassical mansion – from which it takes its name – and a series of interconnected pavilions that form an organic whole centered around a continuous looping path that winds through a sculpture garden overlooking the North Sea.

Conceived and directed by Knud W. Jensen in the mid-1950s, the museum initially served as a vital platform for the promotion of Scandinavian modern art. But it quickly expanded its vision to become an international hub for contemporary art. Over the decades, the museum has undergone progressive evolution, marked by continuous additions masterfully designed by Jørgen Bo and Vilhelm Wohlert. The Louisiana’s architectural ensemble is home to a diverse range of art forms, from painting and sculpture to music, film and design. Characterized by its discreet architecture, the museum harmoniously coexists with its natural surroundings, drawing visitors into a seamless blend of indoor and outdoor spaces. Visitors find themselves immersed in an environment that strikes a delicate balance between tranquility and stimulation, offering moments of contemplation amidst moments of relaxation.

- Project:

- Jørgen Bo, Wilhelm Wohlert with Claus Wohlert

09

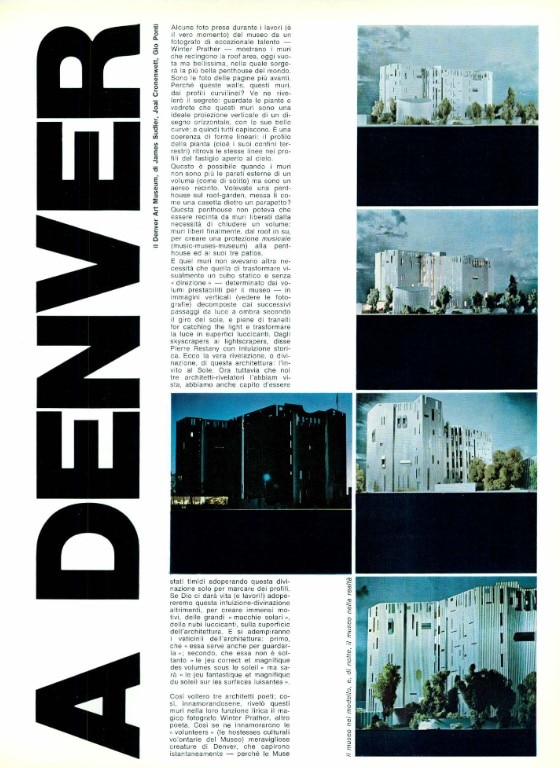

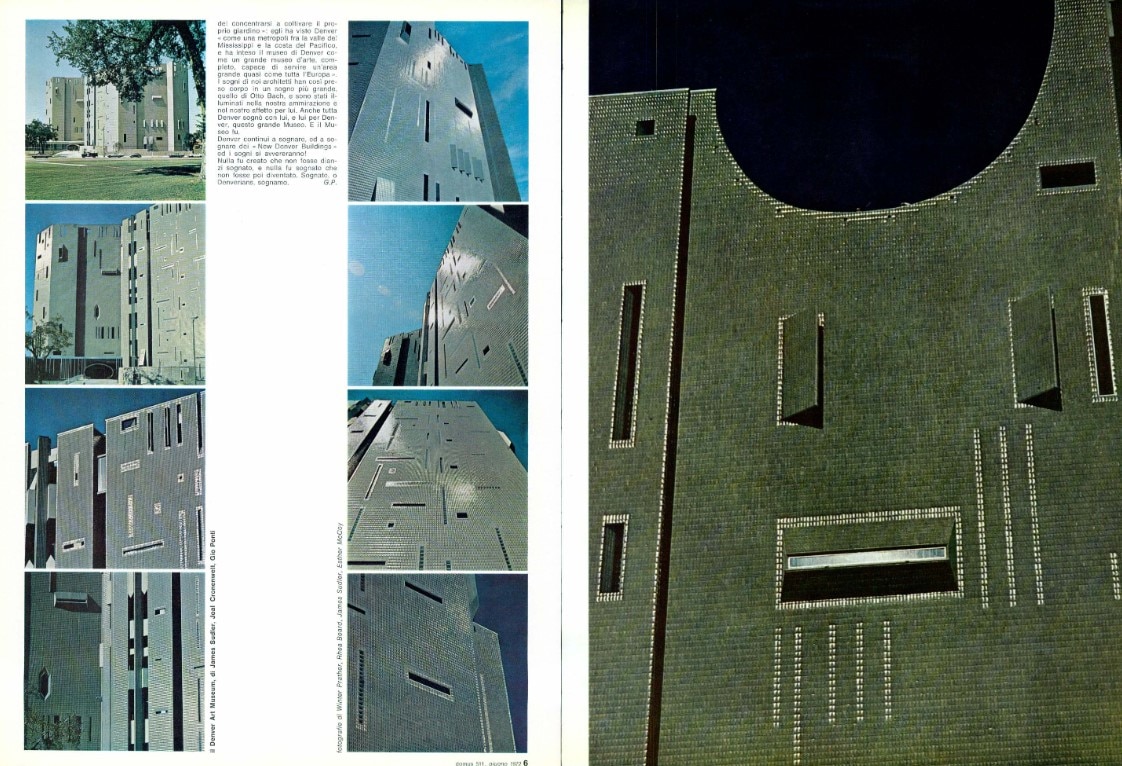

Denver Art Museum

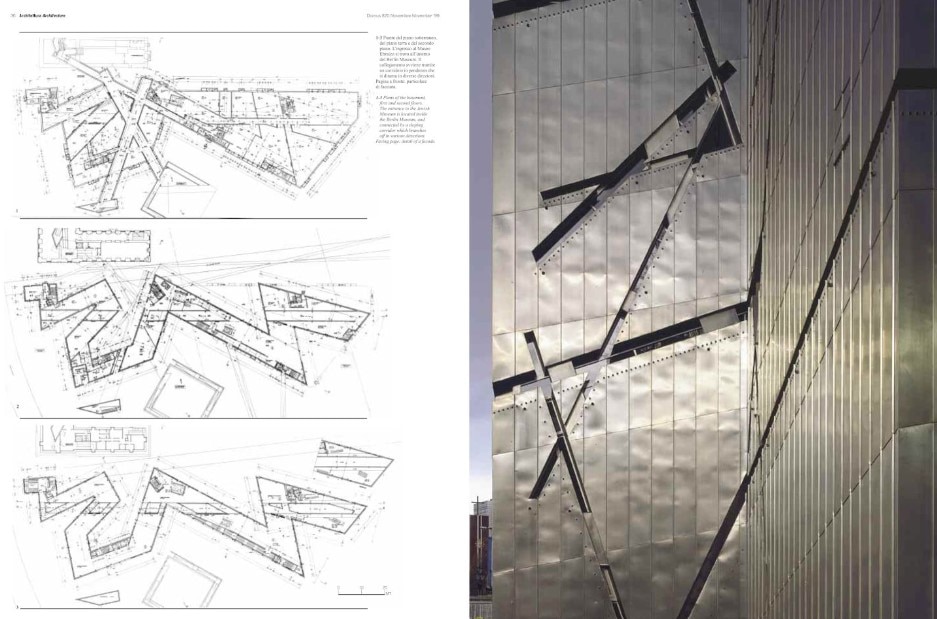

Denver, USA, 1971

Domus 511, June 1972

Emerging as one of the pioneering museums designed to rejuvenate areas beyond the traditional art hubs, the Denver Art Museum stands against the dramatic backdrop of the Rocky Mountains. At the age of 80, Ponti, alongside Joal Cronenwett and James Sudler, crafts an architectural manifesto that embodies his late-career philosophy – that “architecture is a crystal”. At the heart of the museum’s design is an asymmetrical seven-story tower, boasting twenty-four sides adorned with three-dimensional, polygonal tiles that create a mesmerizing play of light and shadow. These tiles, akin to “light-catching traps”, shimmer and reflect light, transforming mundane surfaces into luminous facades. There are no traditional windows, but long and narrow slats – both vertical and horizontal – that shield and modulate the intense natural light while framing vistas of the city and mountains. Bold and innovative, the museum purposefully diverges from the surrounding built environment – initially sparking controversy – preferring instead to engage in a dialogue with the sky, the sun, and the natural terrain. In Ponti’s vision, “art is a treasure to be defended”, and thus the museum is conceived as a sanctuary, a fortress of cultural heritage.

A striking, freeform aerial enclosure, shaped to interact with the winds, crowns the structure, evoking comparisons to a “musical (music - muses - museum)”. Ponti’s fervent declaration upon introducing the museum – “Nothing has come true that has not been dreamed of before” – captures the visionary spirit behind the project. In 2006, an extension by Daniel Libeskind connected sharp volumes to the original building for exhibition spaces, while a recent meticulous restoration and expansion introduced a new atrium and reception areas.

- Project:

- Gio Ponti

- Extension:

- Daniel Libeskind

- Second extension:

- Machado Silvetti Architects, Fentress Architects

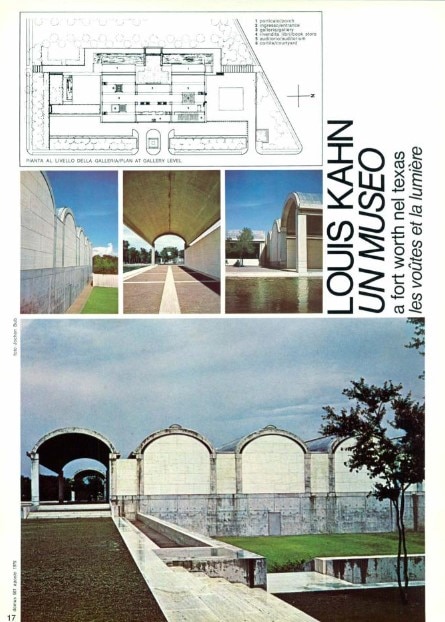

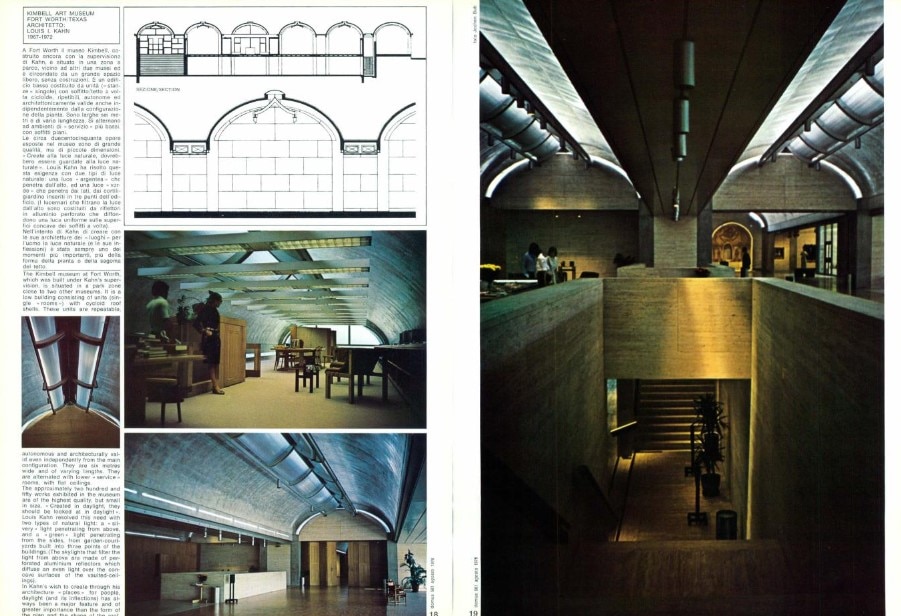

10

Kimbell Art Museum

Fort Worth, USA, 1972

Domus 561, August 1976

View gallery

View gallery

Louis Kahn’s design ethos culminates in the Kimbell Art Museum, where form and function, proportion, distribution, materiality, and light converge in perfect harmony.

Nestled within the confines of an urban park, the museum consists of a series of low, parallel, vaulted longitudinal spaces, each meticulously designed to harness the transformative power of light. Kahn’s vision was to create an environment that would elevate the works of art jealously housed within, in a setting that is at once classical and metaphysical. The museum’s primary source of illumination is pure zenithal light, emanating from the center of the exposed concrete vaults through openings filtered by undulating perforated aluminum reflectors. In addition, a more earthy, horizontal light infiltrates the space through subtle incisions in the facades of the open interior courtyards and from the exterior concrete and travertine perimeter. Surrounded by a wealth of significant museum architecture, including Philip Johnson’s Amon Carter Museum and Tadao Ando’s Museum of Art, the Kimbell remains a cornerstone of cultural significance. Renzo Piano’s 2013 expansion of the Kimbell Museum seamlessly integrates with Kahn’s original design, providing additional space for temporary exhibitions and an auditorium. Characterized by a more open layout with transparent perimeters, Piano’s intervention prioritizes the distribution of zenithal light to further enhance the viewing experience of the artworks on display.

- Project:

- Louis Kahn

- Extension:

- Renzo Piano (Rpbw Architects)

11

Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges Pompidou

Paris, France, 1977

Domus 503, October 1971

This project was immediately such an extraordinary case of typological innovation that it changed the fate of many new museums around the world. Nearly seven hundred designs were presented at the international competition. The winning project, by a group consisting of a very young Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers together with Gianfranco Franchini, proposed the radical idea of a brand new “display machine.” A gigantic spaceship landed in the ancient context of the city of Paris to openly deal with contemporary culture and the future, as a new “active information center” in conjunction with the whole world of arts, design, literature, music, and cinema. A wide, sloping plaza creating urban unity through spatial continuity leads to the entrance under the main façade, five stories high above ground. It’s a combination of the huge, exposed structures forming horizontal walkways and the characteristic diagonal sequence of everted flights of stairs. The building, and both its long gestation and realization process, sparked some initial controversies and protests for its unconventional program, which was intended to be quite disruptive at a time when culture demanded bold and forward-looking actions. So much so that even today, this museum admired all over the world is a very current “tool” in the service of art.

- Project:

- Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers with Gianfranco Franchini and Susan Jane Brumwell

12

Musée d’Orsay

Paris, France, 1986

Domus 679, January 1987

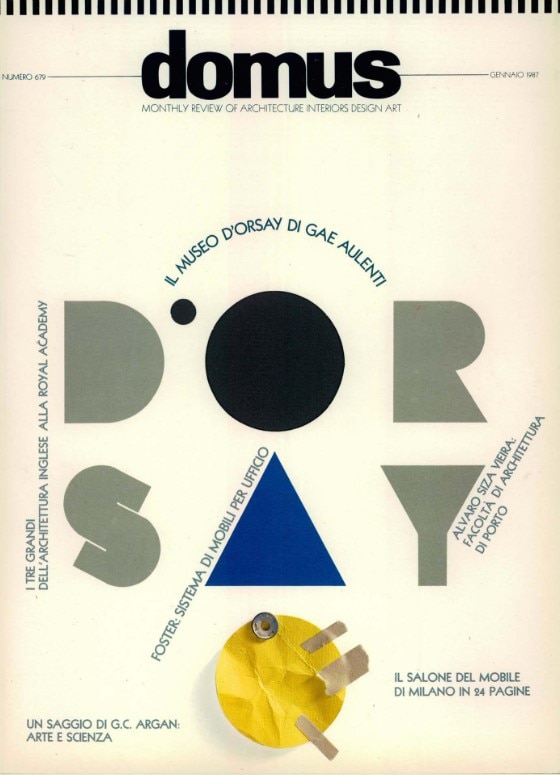

Another Parisian museum, another “Italian” architecture; however with opposite premises from the revolutionary Beaubourg. Designed by Gae Aulenti and repurposed from an old train station, the Musée d'Orsay is dedicated to showcasing 19th-century art, aiming to honor the era depicted in its collections through a language infused with postmodern nuances. With the artwork boasting a significant decorative element, the architecture opts for restraint and formal precision, aiming to transform the bustling crowds of passengers of the former station into an orderly flow of visitors within the new museum. Beneath the large illuminated and decorated vault, the once monolithic and static structure of the building's edges becomes three-dimensional and dynamic. This transformation is made possible by a unified distribution system, organized lengthwise along an inclined section with ascending steps. The art pieces are thoughtfully arranged within heterogeneous areas, fostering new connections between the myriad languages and techniques of the heroic industrial period that both preceded and inspired subsequent artistic avant-gardes.

- Project:

- Gae Aulenti

- Design of the original building:

- Victor Laloux

- Set-up project:

- Gae Aulenti, Valérle Bergeron, Monique Bonadei, Giuseppe Raboni, Luc Richard, Marc Vareille, Emanuela Brignone, Colette Chehab, François Cohen, Nasrine Faghi, André Friedli, Pietro Ghezzi, Francois Lemaire, Yves Murith, Margherita Palli, Italo Rota, Jean-Marc Ruffieux, Gérard Saint Jean, Takashi Shimura

- Lighting design:

- Piero Castiglioni

- Restaurant:

- Estudio Campana

13

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso

Genoa, Italy, 1949 - 1962

Domus 408, November 1963

View gallery

View gallery

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Daria Vinco

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Daria Vinco

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Jacopo Baccani

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Carlo Alberto Alessi

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Daria Vinco

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Daria Vinco

Gallerie Comunali di Palazzo Bianco e di Palazzo Rosso, Genova, Italia

Photo Jacopo Baccani

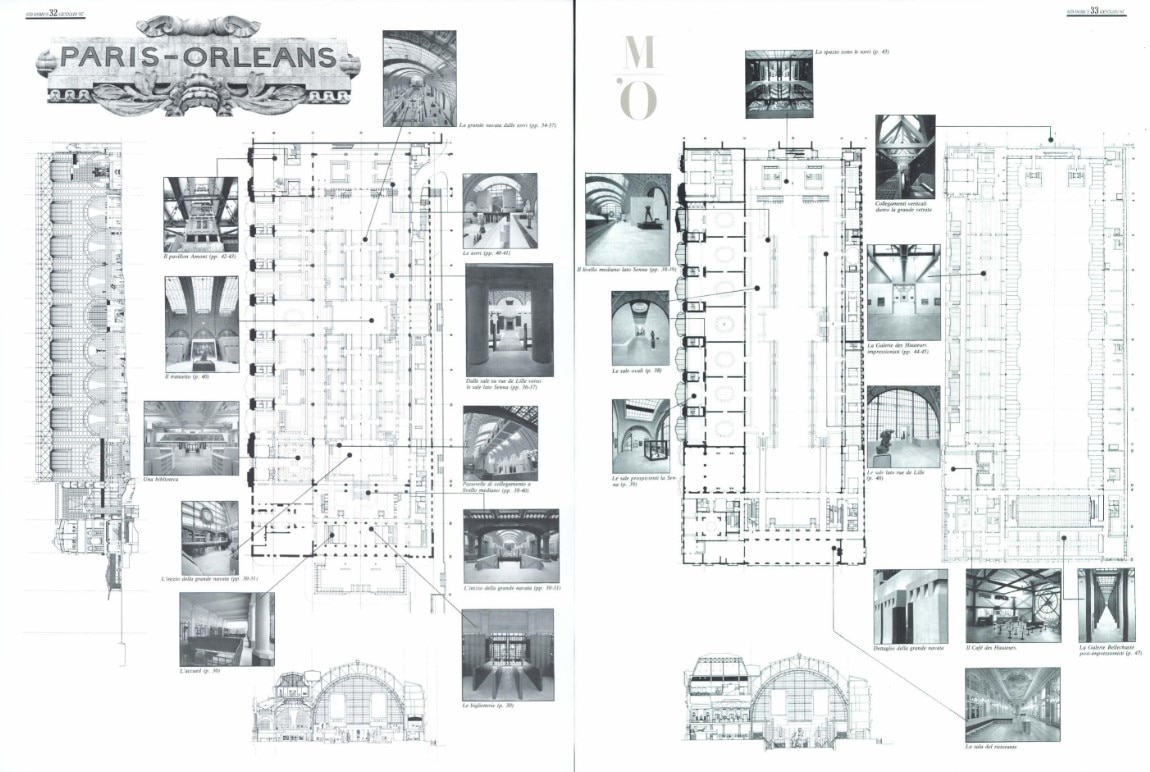

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy witnessed the emergence of an intellectual and cultural discourse involving architects, urban planners, historians, critics, and museum directors. This dialogue addressed critical topics such as the reconstruction of historic centers, the interplay between antiquity and modernity, and the adaptive reuse of monumental buildings as cultural institutions. Many of these edifices, which had been private residences for centuries, were repurposed for public use, serving as venues to exhibit artwork to the broader populace. Among the pioneers confronting the challenges of modern museography was Franco Albini, whose visionary projects remain unparalleled to this day. Starting in the late 1940s, Albini designed and revitalized three museums in Genoa, constituting a fundamental chapter in global interior architecture and exhibition design. These include the Galleries of the White Palace (Palazzo Bianco) and the Red Palace (Palazzo Rosso), two historic aristocratic structures facing each other in the city’s historic center, and the Treasure Museum of St. Lorenzo Cathedral nestled beneath the cathedral itself. Domus documented these masterpieces recently opened to the public using chronicles of the time, words filled with an awe that entering these places still generates. With minimal resources but clear, insightful concepts, Albini managed to work “miracles.” After all, the designer himself used to say that “there are no ugly objects.

- Project:

- Franco Albini

- Original design of the building:

- Pietro Antonio Corradi

14

PAC, Padiglione Arte Contemporanea

Milan, Italy 1954

Domus 408, November 1963

Milan never had a contemporary art museum, which technically could also be seen as a contradiction between the past and the present. However, the city boasts another kind of program: a free space without a collection. It could be called a Gallery, as in Europe it is called a Kunsthalle, and it is basically a flexible architecture dedicated to temporary and experimental exhibitions that investigate the present of the arts. Immediately after World War II, Ignazio Gardella was called to design the Padiglione Arte Contemporanea (P.A.C.) in the spaces occupied by the stables of the nearby Villa Reale, at the Porta Venezia Gardens. The solution proposed and realized, which is still perfect for the purpose, evokes values such as harmony, clarity, essentiality, and measure. The pavilion is an uninterrupted sequence of continuous spaces where there are three different zones at three different levels: the primary area made of tall, parallel, modular aisles with large movable casements and diffuse zenithal light, the upper gallery without openings and with natural light cascading on the walls, and the lower gallery with large windows overlooking the private garden. A refined interior architectural work produces a natural flow between the various areas, defined by polygonal surfaces that “unfold” the space.

- Project:

- Ignazio Gardella

15

Musei Civici al Castello Sforzesco

Milan, Italy, 1956

Domus 824, March 2000

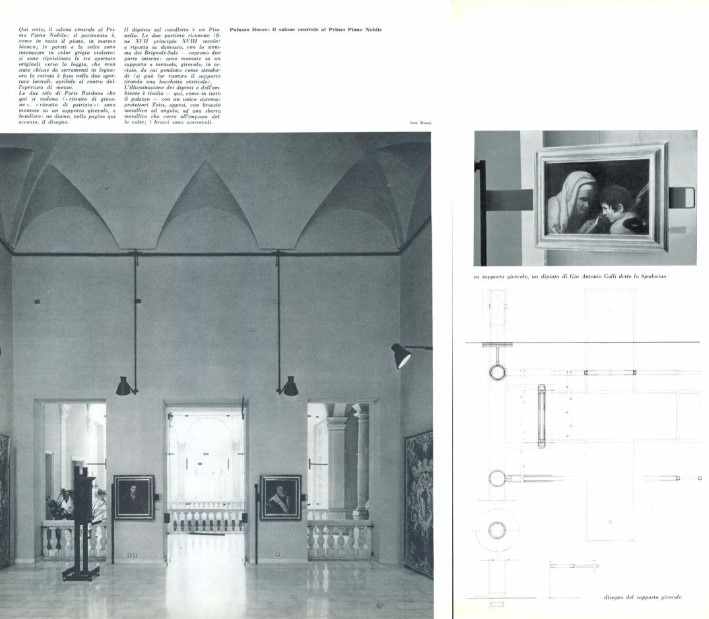

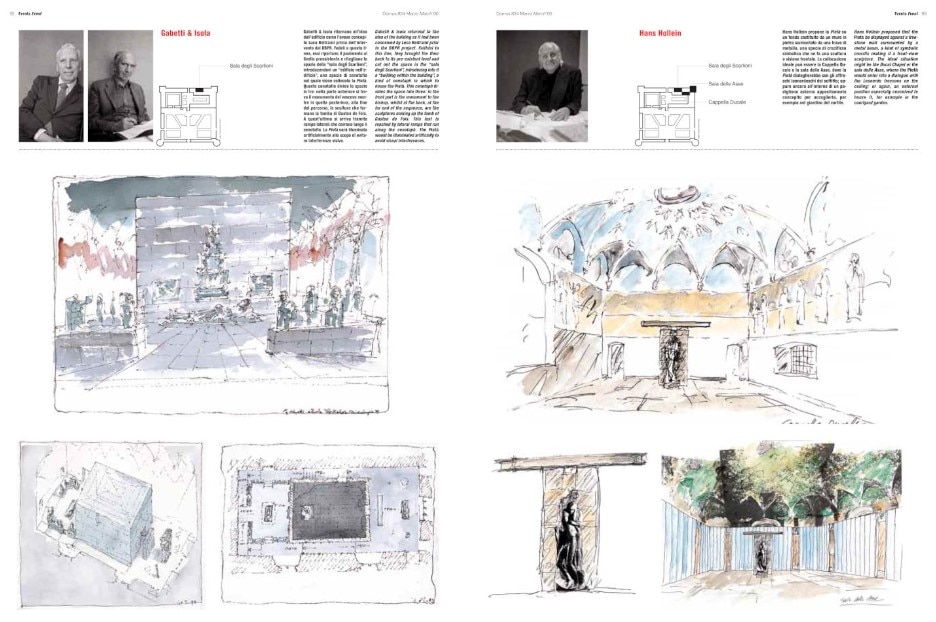

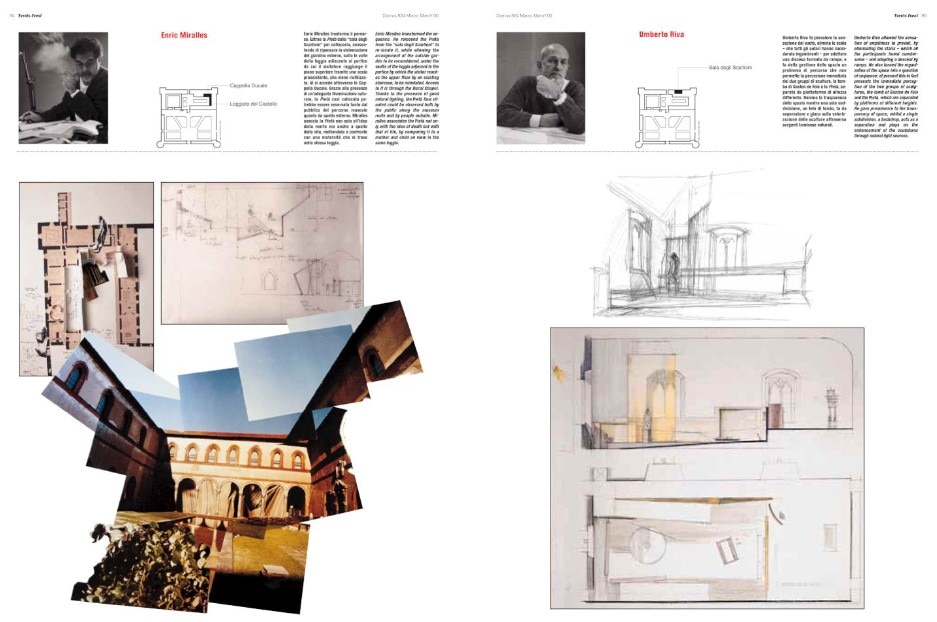

As part of the extensive reconstruction, renovation, and restoration efforts following the devastation of World War II, the Castello Sforzesco in Milan underwent a significant redevelopment and functional reassignment project, which included the reorganization of the Musei Civici galleries around the Cortile della Rocchetta and the Corte Ducale. The dialogue between the city’s rich historical collections and the architectural that envelops them, essentially a museum within a museum, generated, through a long sequence of objects, new spatial dynamics, offering moments of contemplation and fluid movement throughout the castle. At a time when Italian architecture and museography set global standards, the B.B.P.R. studio wrote a fundamental chapter with this project, crafting a narrative as complex as it was cohesive, focusing on the concept of “architecture within architecture,” epitomized by the revered Michelangelo’s Pietà Rondanini. The sculpture’s magnetic allure prompted an international competition in 1999 for its reinstallation, ultimately won by Alvaro Siza’s design, although it remained unrealized. Subsequently, in 2015, after protracted deliberations fraught with controversy and criticism, a decision was reached to relocate the Pietà Rondanini to an independent wing, the Spanish Hospital, as envisioned by Michele De Lucchi, constituting an independent museum made of a single work.

- Set-up project:

- B.B.P.R.

- Renovation:

- Michele de Lucchi

16

Museo di Castelvecchio

Verona, Italy, 1956

Domus 369, August 1960

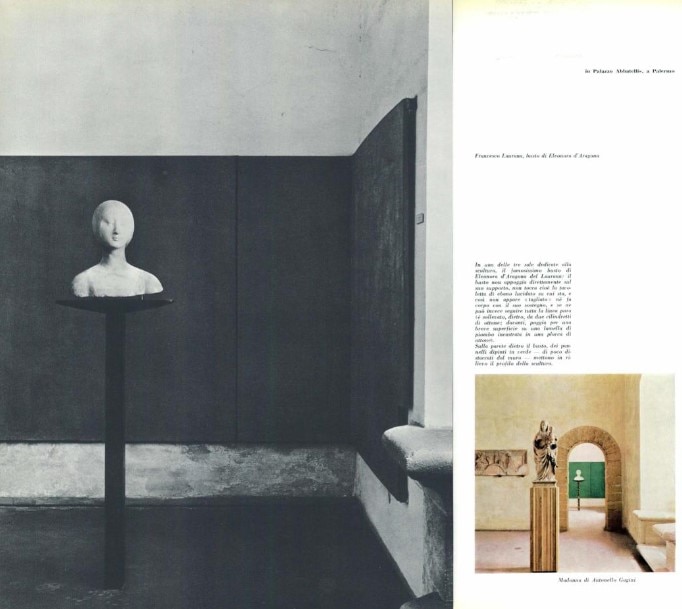

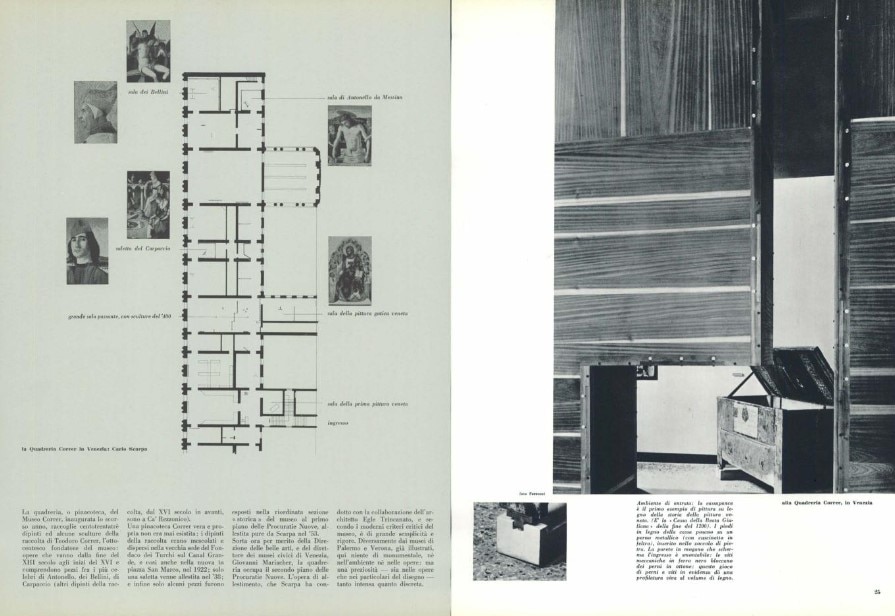

When Carlo Scarpa started his restoration and redevelopment project of the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, he had already demonstrated a refined practice and admirable ability to work in an existing historical context to set up temporary exhibitions and permanent galleries. Indeed, he had already done so for the National Museum of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo (1954) and the Gipsoteca Antonio Canova Museum in Possagno (1957). In this case, Scarpa immersed himself even more carefully, if possible, and for a long period, in the new museographic idea of the post-war era. A conception whereby, given an ancient container, contemporary architecture studies it, understands it, modifies it, and enhances it, even with concessions to new interventions and demolitions, which were criticized at the time but fortunately implemented. His work is still exemplary today, characterized by a few carefully thought out and designed elements down to the smallest detail to enhance the works and the container space. The path throughout the castle’s various sections is highly articulated, but the two main parts, near the new entrance, are identified on the ground floor with the sculpture gallery and on the first floor with the paintings, where every position – every base or support – is perfectly studied and restudied, set up and reset up, until finding the right spatial balance between contemplative stops and movement.

- Project:

- Carlo Scarpa with Arrigo Rudi and Carlo Maschietto

17

Scuderie Ducali and Galleria Nazionale della Pilotta

Parma, Italy, 1963 - 1983

Domus 429, August 1965

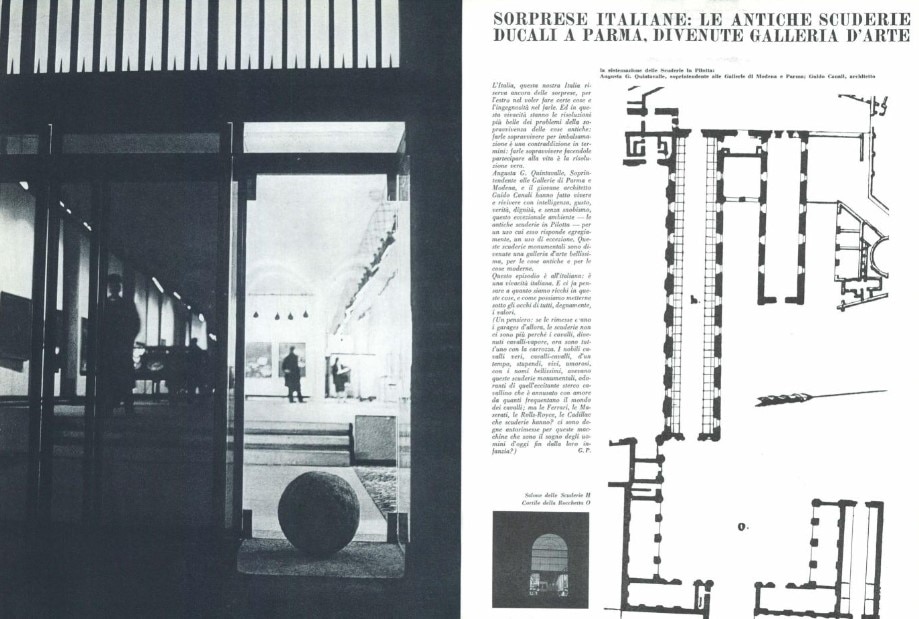

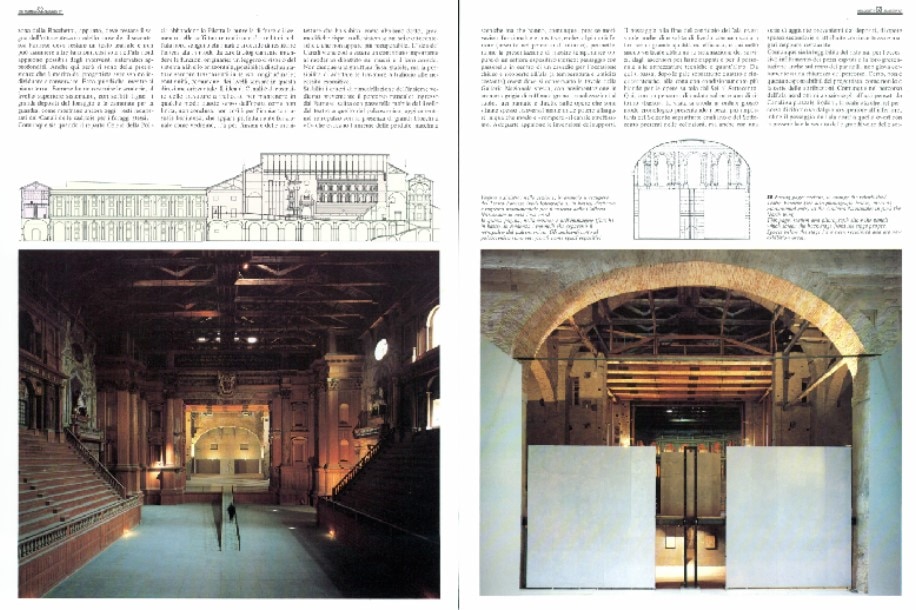

In years of reconstruction of Italy’s artistic and architectural heritage, the issue of musealization of ancient residences arose in Parma as well. The first intervention concerned the ancient stables of the Palazzo della Pilotta, which since the 19th century have seen a gradual entry of artworks replacing military and governors in the service of the Farnese family. The designer, a young Guido Canali, did not think of embalming an architectural monument but rather its participation in cultural life. The courageous arrangement of the stables into exhibition halls confronts the limitations imposed by numerous original elements from the 17th century, slowly deteriorated by misuse: a linear central platform is then adopted, isolated and elevated, containing installations and from whose edges exhibition panels and display case structures were anchored, along with all the equipment for point lighting. The exhibition surfaces, wooden panels covered with stretched canvas, were therefore detached from the existing perimeter.

In the mid-1980s, Canali returned for a much more ambitious and imposing project dedicated to the National Gallery, with large tubular lattice metal trusses, planks, tension cables, walkways, and mats to support all the exhibition elements and give a sensation of an unfinished work, in perpetual progression, an adaptable system to be able to meet all exhibition needs.

- Project:

- Guido Canali

18

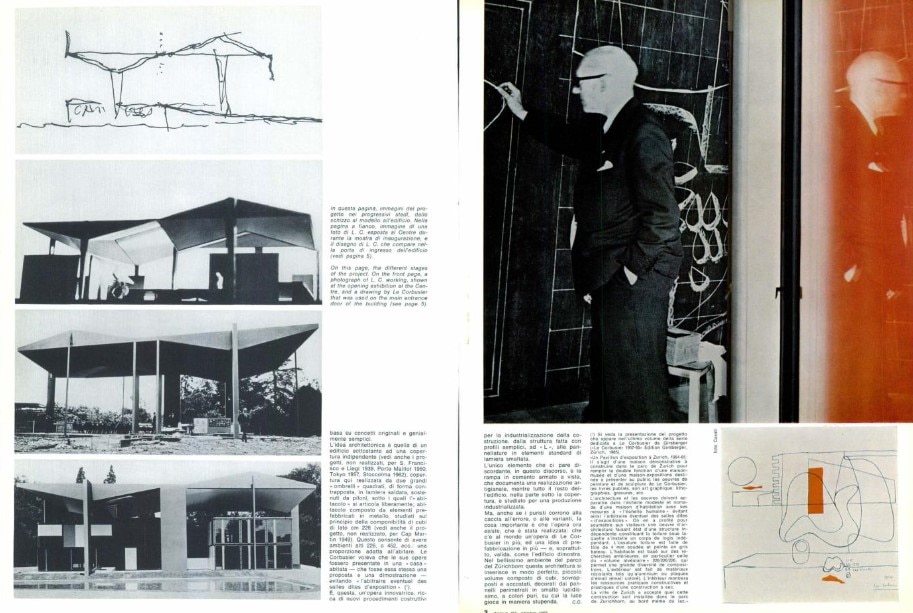

Pavillon Le Corbusier

Zurich, Switzerland, 1967

Domus 455, October 1967

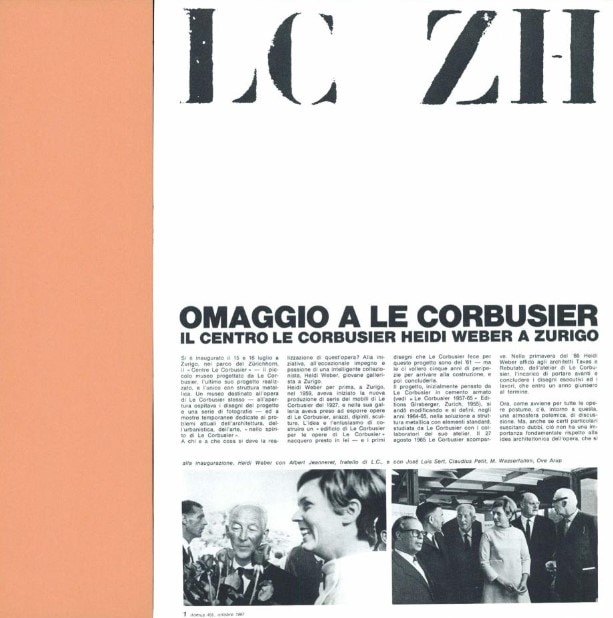

Originally conceived under the name ‘Maison de l’Homme’ and intended to exhibit his work in design and architecture, this museum is the last project realized by Le Corbusier, who unfortunately did not live to see its completion, and it was finished posthumously. Heidi Weber was a gallery owner who promoted his work and here she wanted to create an exhibition space set up like a residence, a place to live and inhabit, dedicated to the emerging problems of architecture, urban planning, and art at that time. Unique among the many works of the Swiss master, it is made up of a metal structure made solely of industrial profiles, sheet metal, and glass, which, around a core of reinforced concrete for the internal stairs, form a pavilion in Zurich’s Park overlooking the lake. Under a polygonal canopy with opposing pitches supported by slender pillars, there is an independent cubic volume made of prefabricated elements and proportioned according to the Modulor measurements. The glass panels alternate in a compositional interplay of opaque horizontal or vertical panels, painted with various fundamental and primary colors.

- Project:

- Le Corbusier

19

Aalto Museum

Jyväskylä, Finland, 1973

Domus, February 2024

View gallery

View gallery

In the heart of Finland, in a town that witnessed the birth and evolution of the architecture of one of the most important designers of the 20th century, stands a museum designed by the very same architect it is dedicated to: Alvar Aalto. Initially commissioned as an Art Museum and conceived by Aalto himself to establish connections between various contemporary arts and architecture, it complements the Museum of Central Finland, another exhibition building previously designed by Aalto. Visiting the museum bearing his name, and conceived for the specific purpose of showcasing his design thinking, not only means immersing oneself in his personal world among documents and history, or in his professional world between design and architecture, but it is also a spatial experience that immerses the visitor in a kind of totalizing work of art. A polygonal volume, clad in white ceramics tracing vertical moldings, houses services and an auditorium on the ground floor, while an exhibition gallery unfolds on the first floor. In 2023, the A-Konsultit studio completed extensive restoration and expansion work on the museum complex, adding an entrance and reception area with shared facilities, connecting the two previous museums, and integrating them into a single museum hub called Aalto2.

- Project:

- Alvar Aalto

- Extension:

- Arkkitehtitoimisto A-Konsultit

20

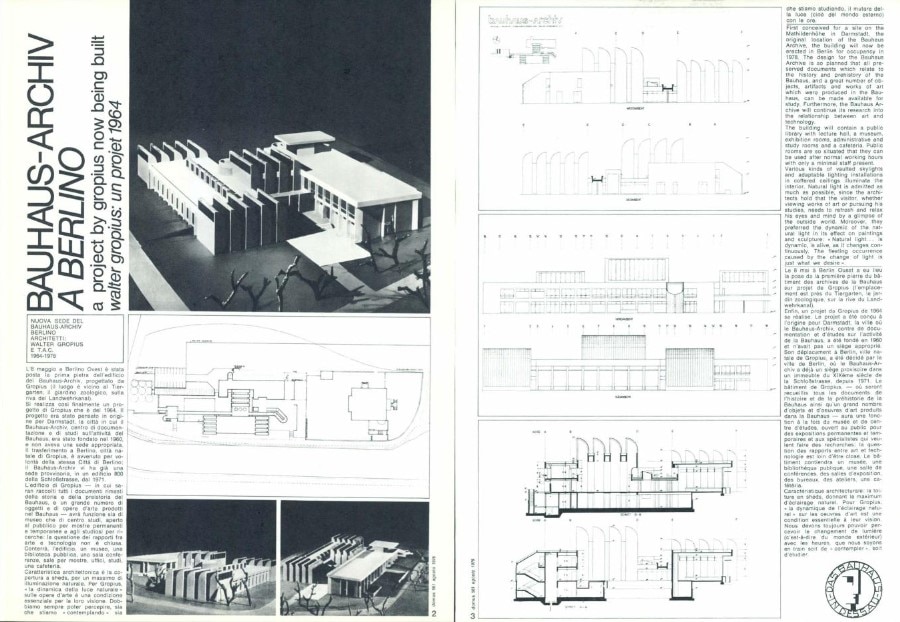

Bauhaus-Archiv

Berlin, Germany, 1979

Domus 561, August 1976

This archive-museum is a research center that celebrates the history of the Bauhaus, a revolutionary school that in a few years changed the course of 20th-century design culture. No one better than its inventor and director, Walter Gropius, could design this museum, returning at the end of his career to his fundamental creation and imagining a place, completed posthumously, to preserve the countless documents and objects that keep its memory alive.

Initially planned for the city of Darmstadt – which confirms the importance of the Bauhaus throughout Germany and not just in its three official locations – the building adapted for Berlin carries with it the language of industrial construction, here dedicated to the production of culture, with the characteristic profile of the shed roof designed to make the best use of natural light for the benefit of the exhibited works.

The exhibition spaces were limited compared to the archive storage spaces, but public interest was growing, so on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the school’s foundation, design competitions are announced to expand the Berlin site (winners Staab Architekten, ongoing) and build new museums in the other two fundamental cities, Weimar where it all began (Heike Hanada, 2019), and Dessau where it all developed (addenda architects, 2019) and where still stands – perfectly preserved museum of itself – the masterpiece building for the school, designed by Gropius himself in 1925.

- Project:

- Walter Gropius

- Extension:

- Staab Architekten

21

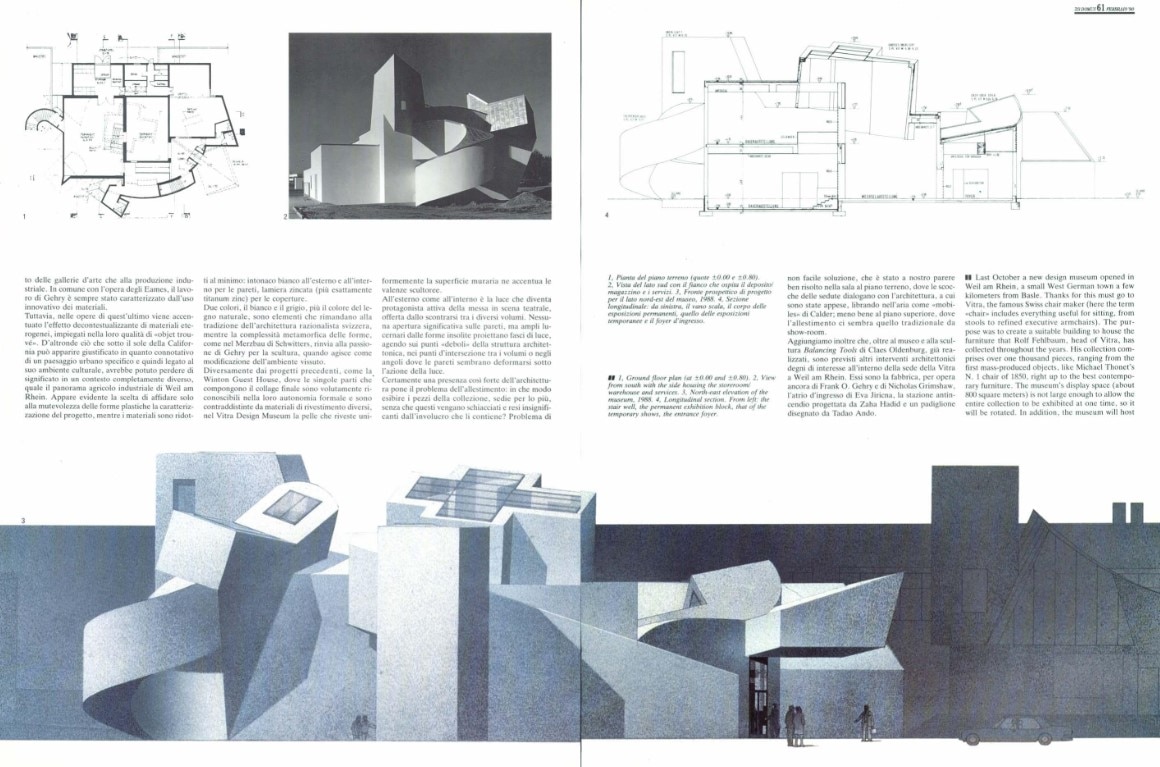

Vitra Design Museum

Weil am Rhein, Germany 1989

Domus 713, February 1990

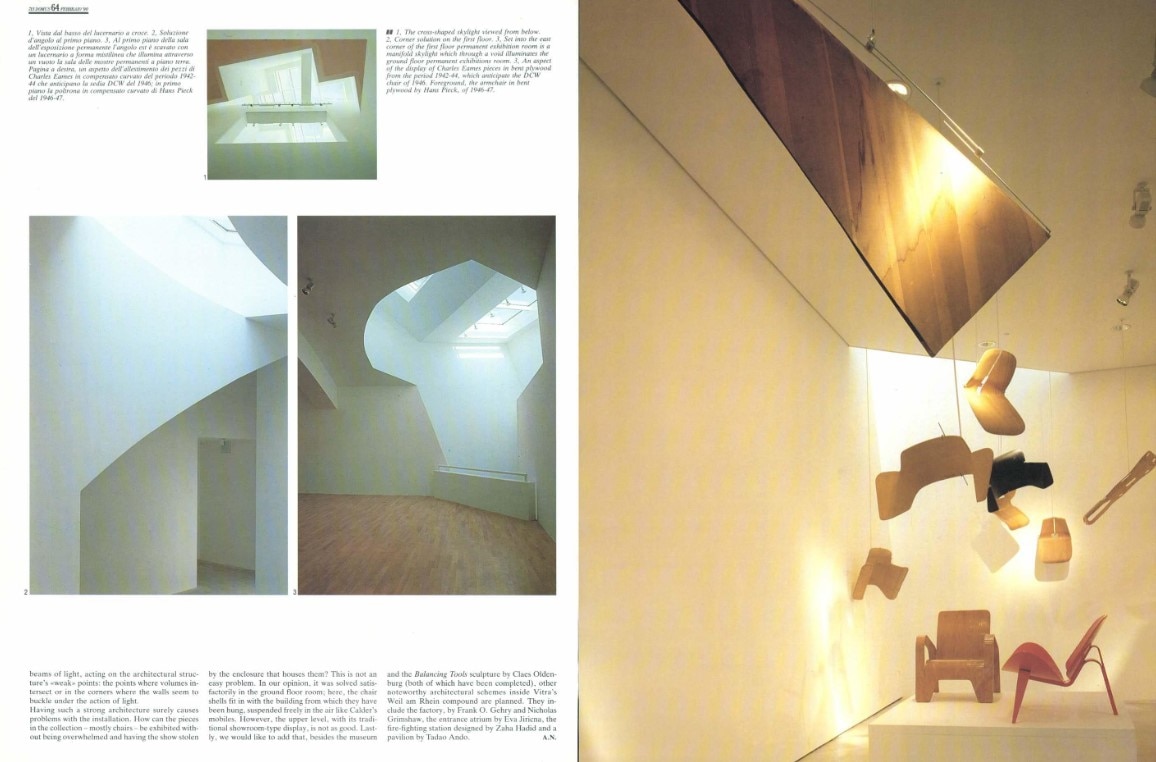

The building designed by Frank Gehry for the Swiss furniture company Vitra can be considered the first museum totally dedicated to showcasing design as industrial production. Initially comprising Vitra's extensive collection of seating and lamps accumulated by the company over the decades, it has since transformed into a structured program of thematic exhibitions. The museum was then able to transform these exhibitions into a "cultural product" to invest in by creating a market for them, offering repetitions and adaptations to be toured worldwide for an extended period of time. The architecture was Gehry's first realized project in Europe alongside an industrial warehouse nearby and it was also among the earliest recognized examples of Deconstructivism. The irregular volume, comprised of curvilinear spaces that expansively stretch in length, width, and height in a quest to harness natural light, immediately raises the issue of the art container, which some critics would prefer to remain as neutral as possible. Today, the Vitra Design Museum is an integral part of the Vitra Campus, an open-air museum of contemporary architecture where many of the most influential figures have made their mark, from Tadao Ando, Zaha Hadid, and Alvaro Siza to SANAA, Renzo Piano, and Herzog & de Meuron. The latter, in addition to the groundbreaking VitraHaus showroom, in 2016 completed the Vitra Schaudepot, the latest museum intervention exclusively devoted to showcasing and enhancing the permanent collection from which it all began.

- Project:

- Frank Gehry (Main building), Zaha Hadid, Nicholas Grimshaw, Álvaro Siza, Tadao Andō, Renzo Piano, Herzog & de Meuron

22

Teatro dell’architettura

Mendrisio, Switzerland, 2017

Domus 1019, December 2017

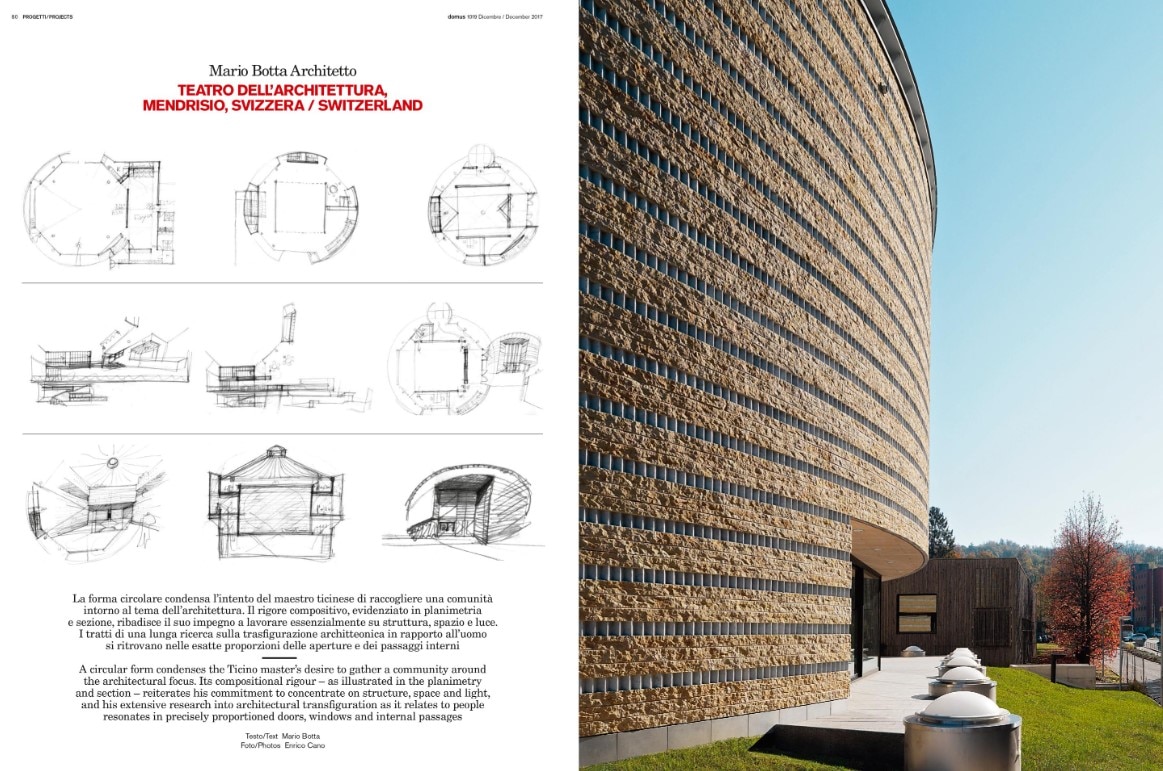

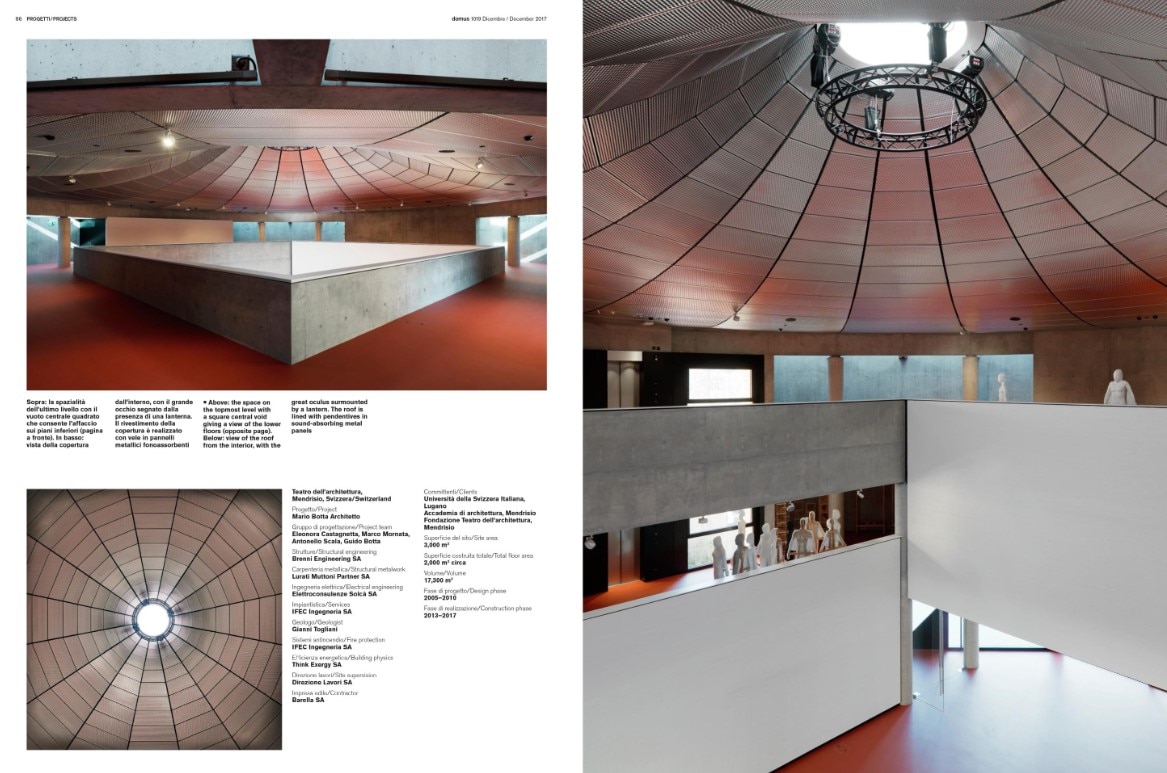

Mario Botta has built numerous museums worldwide, with the most extensive and renowned undoubtedly being the MoMA in San Francisco (1995). However, this more recent project truly testifies the significance of Botta's cultural legacy in architectural education, epitomized by the establishment of the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio (1996). This museum marks the culmination of a twenty-year cycle, integrating the functions of the Swiss campus and accentuating profound nuances and values that further elevate the project's importance and societal relevance. Under the name "teatro" (theater), this museum space is uniquely crafted to showcase the myriad variables and intersections of architecture with other disciplines such as design, fashion, photography, film, dance, music, and literature. The structure evokes that of anatomical theaters, featuring balconies at various levels encircling a central space, offering different perspectives on the live experience. The result is a monolithic cylindrical structure spanning three levels above ground, with an empty cube nestled within, enveloped by numerous galleries that face the soaring, full-height space designated for exhibitions. All topped by a luminous funnel-shaped ceiling.

- Project:

- Mario Botta

23

Lascaux IV - Centre International de l’Art Pariétal

Montignac, France, 2016

Domus, April 2017

The Lascaux site is the oldest “museum” in the world, where approximately 20,000 years ago, our ancestors engaged in cave painting to mark a ritual space within the pregnant womb of the earth. The origin and purpose of these drawings are still not fully understood, but this magical place represents the oldest discovered starting point for our design, artistic, and architectural culture. Archaeology and architecture share the same root and perfectly overlap here: the former gazing at the past, the latter to the future. The new museum is the latest project in a series of satellite research and service structures dedicated to the protected heritage of the painted caves and it is intended for broader public education and dissemination. The design by Snøhetta and SRA has a compact, meandering form that creates a significant cleft in the ground, with artificial grottos housing the exhibition spaces narrating the ancient history of the site. The most astonishing feature, crafted by the Casson Mann studio, and possibly reigniting the modern debate between originality and reproduction, is the faithful and three-dimensional scenic reconstruction of segments of the painted ceilings, enabling visitors to grasp the essence of this earliest artistic masterpiece of humanity.

- Project:

- Snøhetta and SRA Architectes, with Duncan Lewis Scape Architecture

- Set-up project:

- Casson Mann

24

La Congiunta

Giornico, Switzerland, 1992

Domus 753, October 1993

View gallery

View gallery

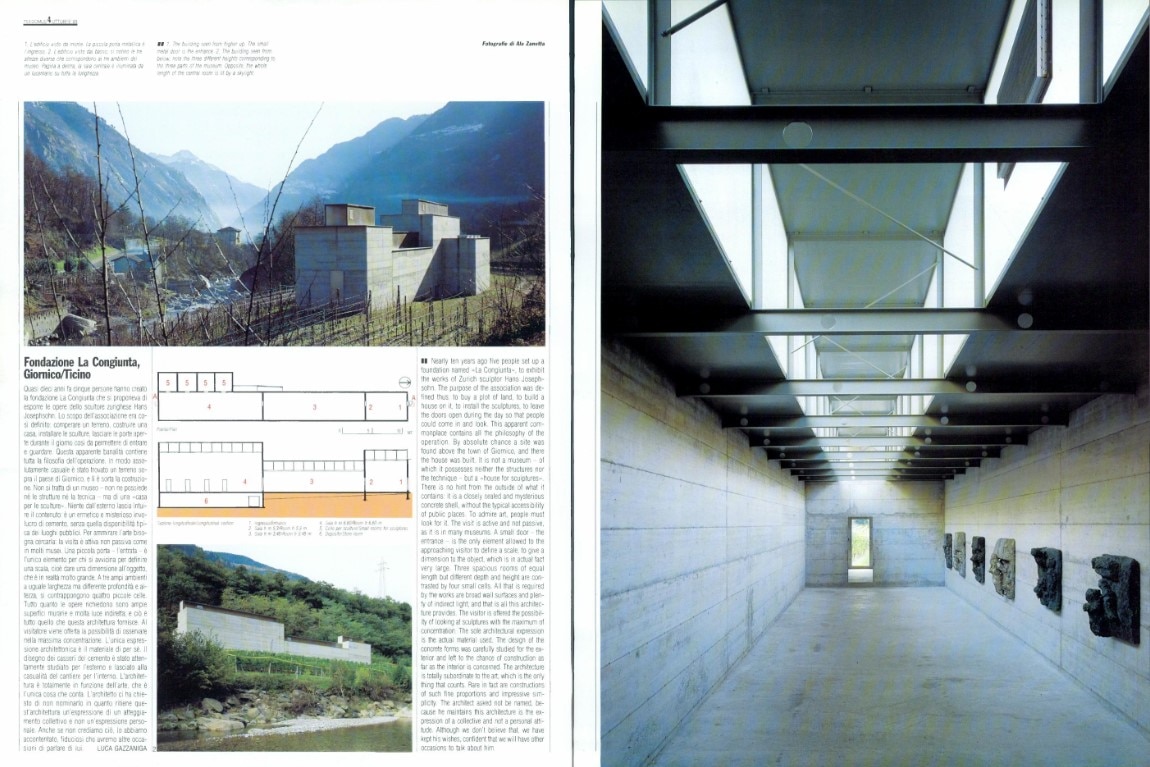

This special architecture isn't a typical museum; however, it can be described as a “home for sculptures,” a space where Peter Märkli designed a lasting residence for the works of Swiss artist and sculptor Hans Josephsohn. The architect initially refrained from calling himself the sole designer, emphasizing that sometimes, as happened in this case, architecture can be “an expression of collective behaviors rather than individual activity.” Isolated amidst fields at the foot of the Gotthard and somewhat concealed – suggesting that art demands to be sought after – this exhibition pavilion stands as a raw reinforced concrete structure, a gallery with three varying heights and a spine of skylights bridging to capture and pour light into the bare interiors. Here, sculptures and bas-reliefs find precise placements within an ethereal and suspended atmosphere, whether it is on walls or floors, or in small groups or individually, or within a sequence of small niches that enhance both the pieces and their unique relationship with the observer. A small door on the north side marks the entrance. It is almost always closed, appearing inaccessible. However, all it takes is a visit to the village's sole inn and a request for the key, which will be promptly provided. Then, the visitor can freely, in solitude and with a sense of responsibility, embark on their journey between art and architecture.

- Project:

- Peter Märkli

25

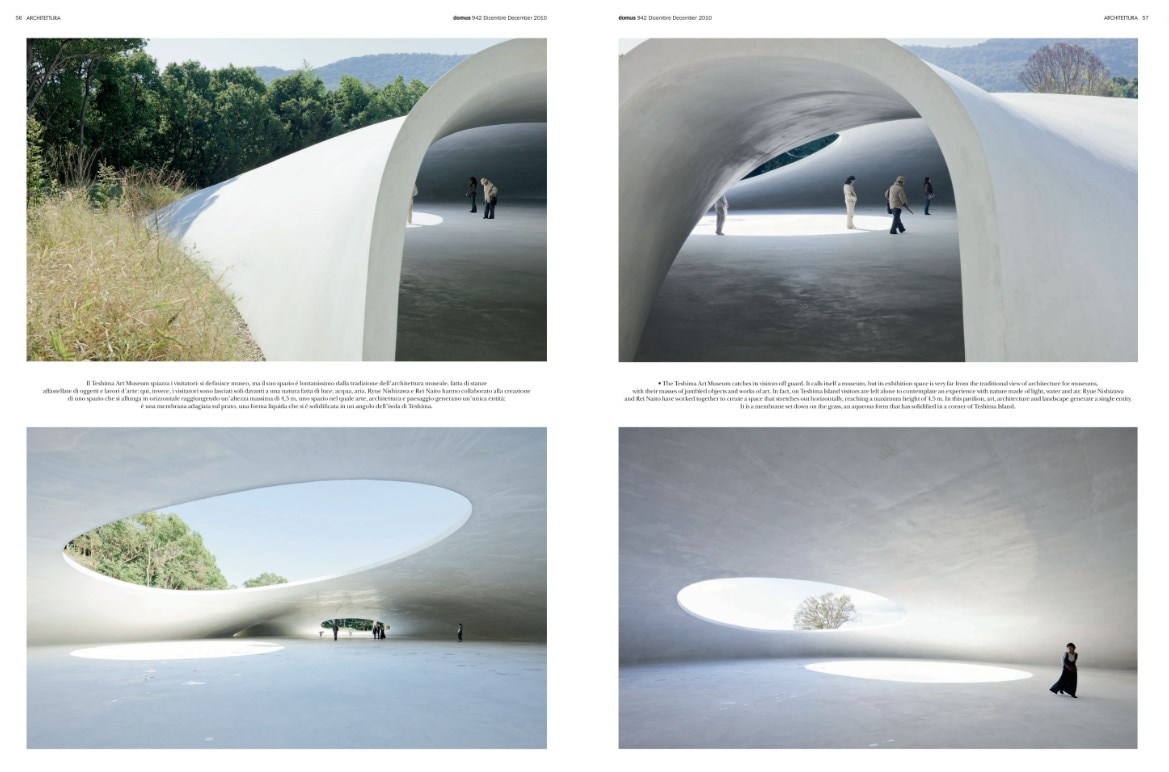

Teshima Art Museum

Teshima, Japan, 2010

Domus 942, December 2010

The division between content and container, between artwork and museum, can sometimes be exceedingly subtle. This architecture, designed by Ryue Nishizawa (partner of Kazuyo Sejima at SANAA, who also develops projects independently), was conceived and crafted in collaboration with Rei Naito, a Japanese artist known for her ultraminimalist works that blur the lines between conceptual art and environmental art. A single, slender membrane of reinforced concrete creates curvilinear hill-like volumes, emerging amidst the undulating fields and forests of an island in Japan's Seto Inland Sea. The structure is made of two bubbles, a smaller one intended for a café and a shop, and the larger one dedicated to the aesthetic experience conceived by the desginer. It's a sensory space where, beneath a vault punctuated by two large circular skylights – be it sunny or rainy −, light, air, and water combine in the ideal atmosphere for contemplating artworks that evoke natural phenomena. Delicate ribbons occasionally hang from the ceiling, swaying in the air, while water droplets emerge from the floor (thanks to a special invention involving a one-sided capillary permeabilization device), flowing into shallow pools that expand or contract, evaporating over time with the seasonal climate change. This museum is part of a comprehensive plan of architectural interventions spearheaded by the Naoshima Fukutake Art Museum Foundation and the Benesse Corporation across various islands of the Seto Inland Sea, aimed at countering the decline of this geographical area by focusing on cultured tourism.

- Project:

- Ryue Nishizawa (Sanaa), Rei Naito

26

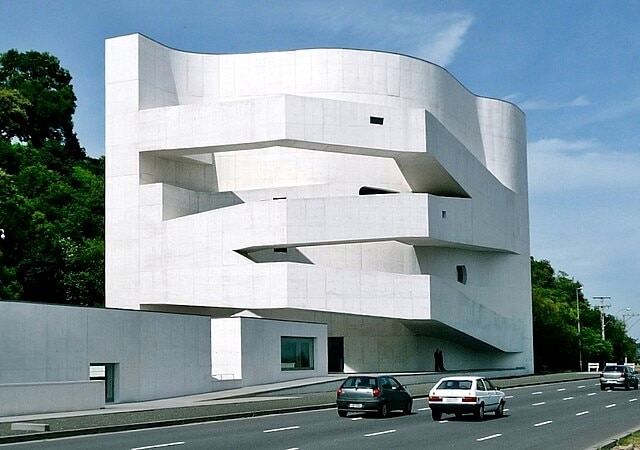

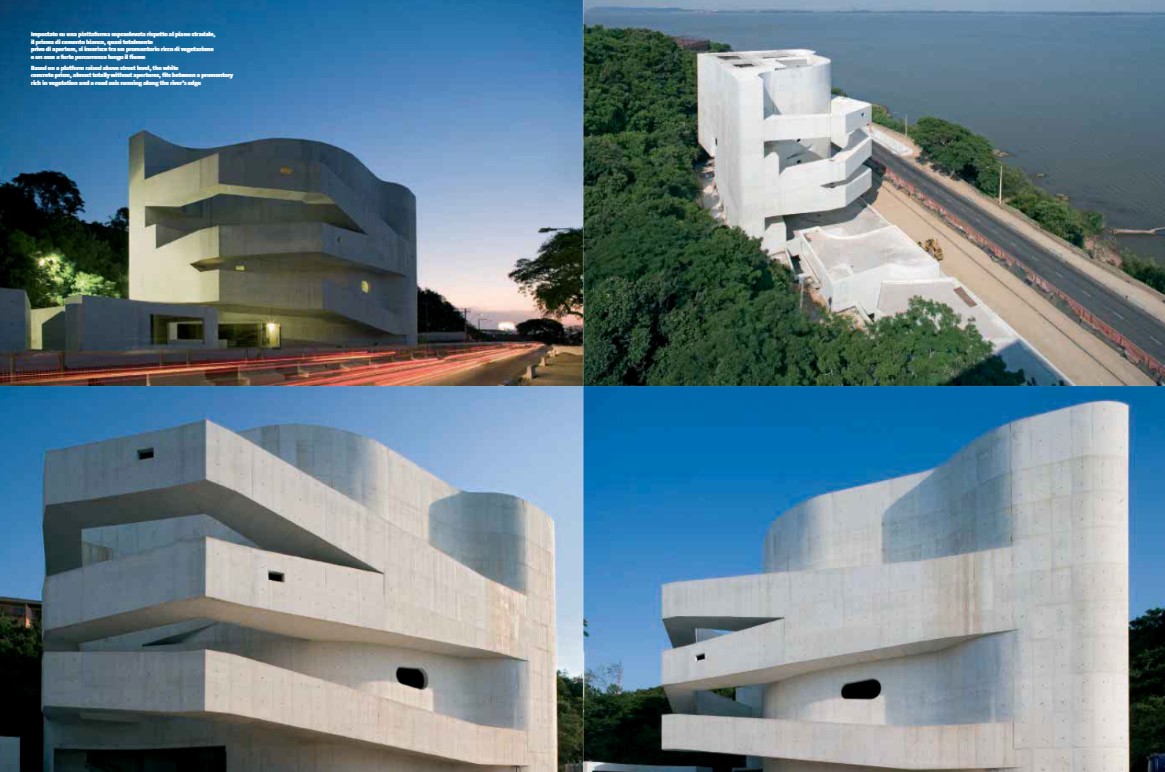

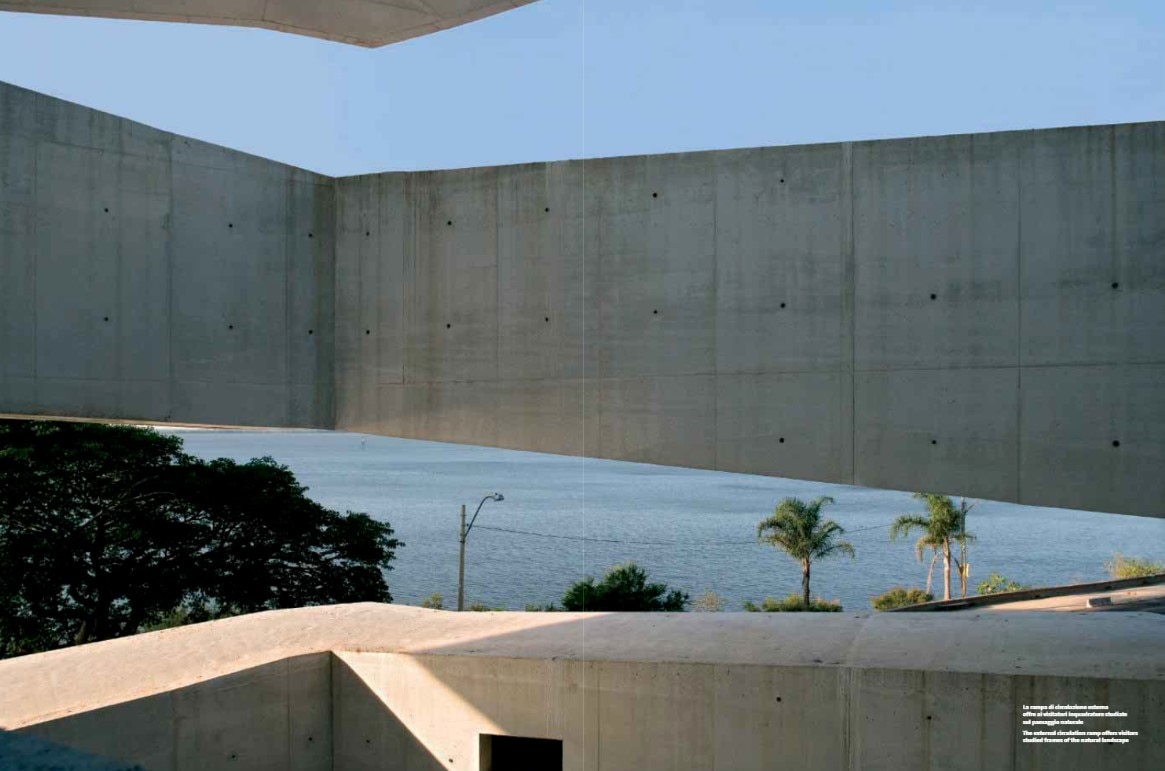

Iberê Camargo Foundation

Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008

Domus 893, June 2006

This museum is the first building that the great master of Portuguese architecture, Alvaro Siza, realized in Brazil to house all the works and activities of the foundation dedicated to one of Brazil’s most important expressionist painters, Iberê Camargo.

In addition to an underground part developed into the slope of the wooded hillside with an auditorium, library, and reception services, the building has its central core in a towering, multifaceted white concrete prism on four levels, housing various galleries overlooking a full-height interior void. Around it unfolds a series of ramps and inclined surfaces, a promenade architecturale on various levels, sometimes internal and other times external to the volume. The aerial circulation ramps that detach from the museum body and remain impressively suspended like tree branches offer visitors peculiar views of the surrounding natural landscape as they traverse them, defining a distinctive and unusual entrance facade for the museum, making it an attractive landmark overlooking the great river.

- Project:

- Alvaro Siza

27

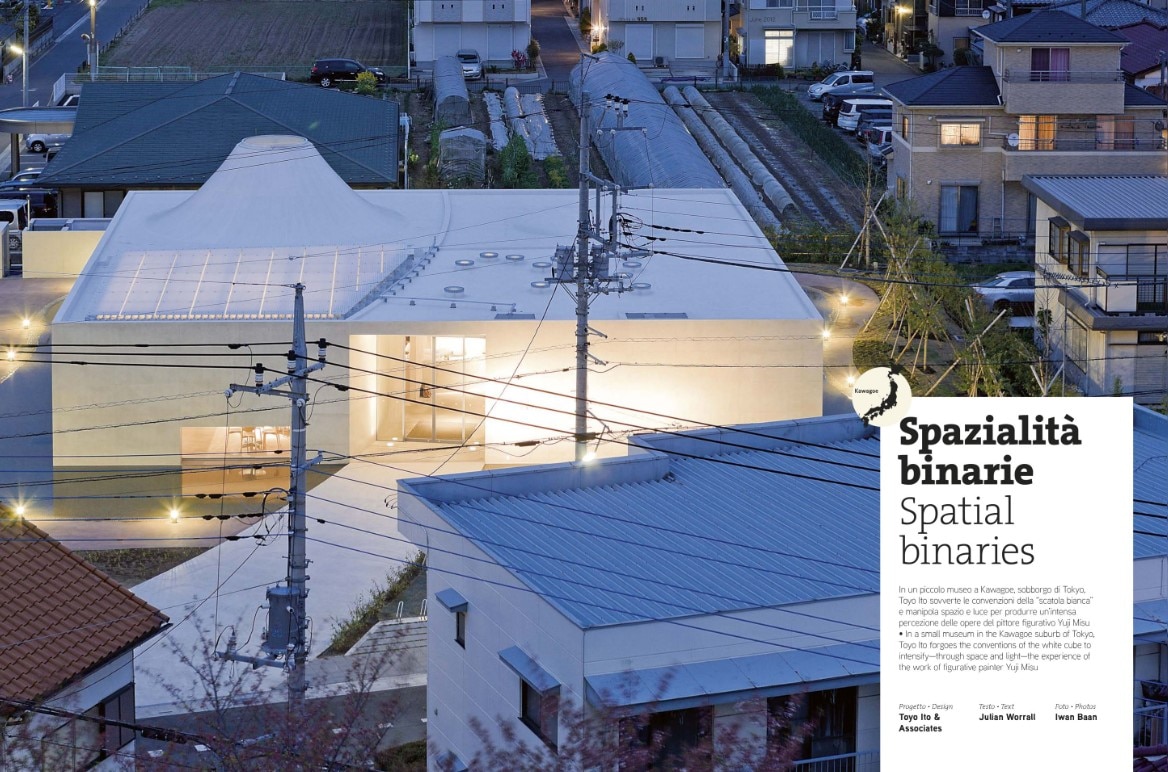

Yaoko Kawagoe Museum

Kawagoe , Japan, 2011

Domus 959, June 2012

In the outskirts of a sprawling metropolis like Tokyo, a small museum supported by a private commission and dedicated to the Japanese painter Yuji Misu becomes an attraction and meeting point for the entire area, in connection with the neighborhood’s public. Toyo Ito did not forego the opportunity to develop a typological, experimental, and specific idea through a project in which the small dimensions do not reduce the interest in the slightest. The building has a single square floor plan, with an internal cruciform and curvilinear division defining four spaces: two dedicated to reception and community space for the neighborhood, and two for the exhibition of paintings. A large paraboloid cone protrudes from below to bring artificial light into the first of these rooms, while another one intrudes from above to bring natural light into the second, characterizing the display of paintings on the walls, divided according to the artist’s two different periods in his language. In a circular path of entrance, viewing, stopping, and reflection, isolating himself from the external context but developing a grid emerging from urban references, Ito managed in a nearly imperceptible but sensitive way to characterize this small museum occasion with the experience of the interior spaces.

- Project:

- Toyo Ito

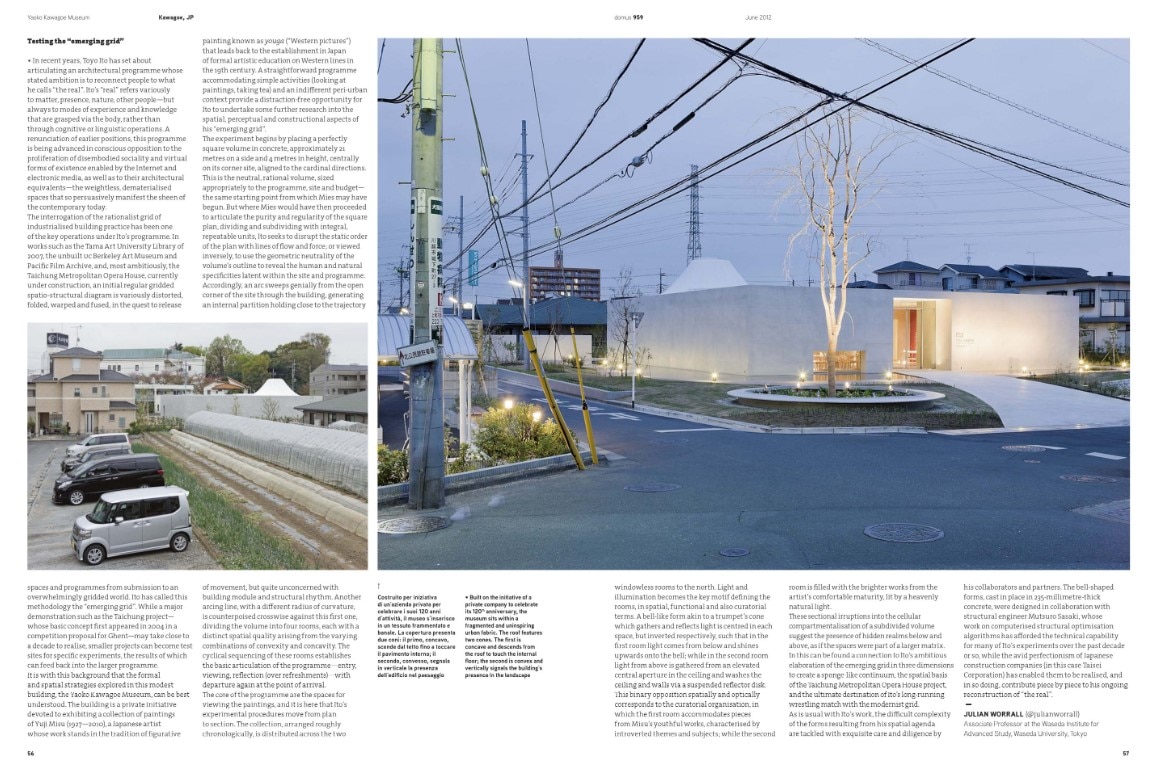

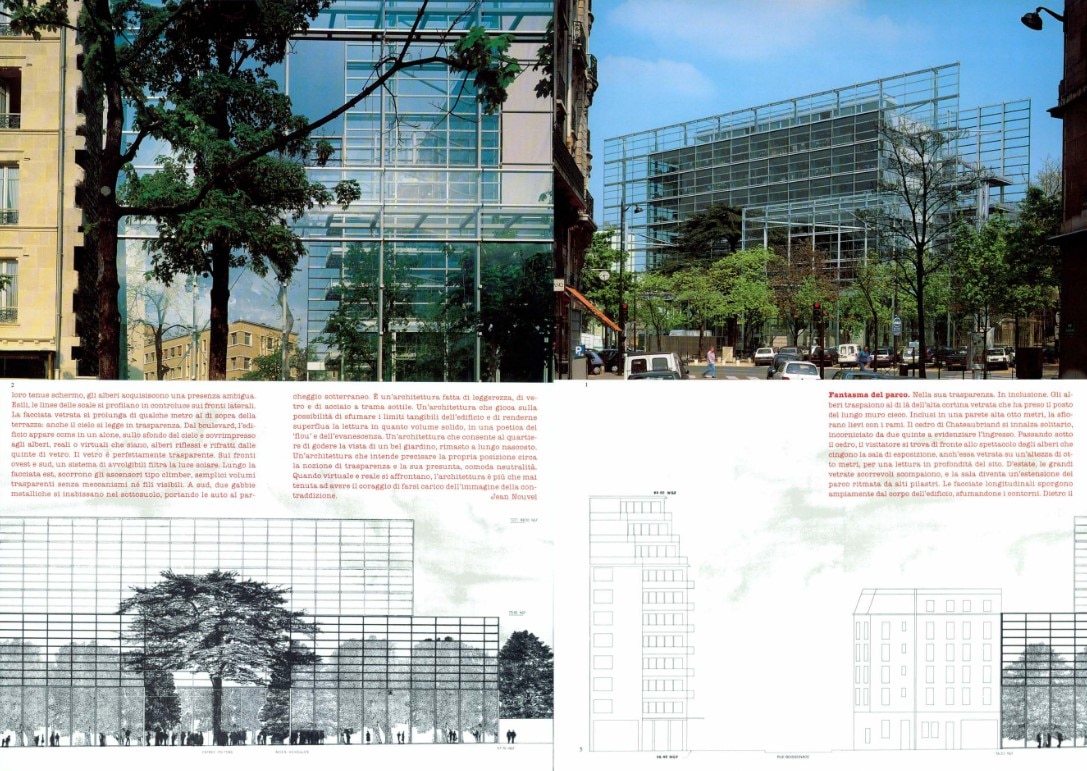

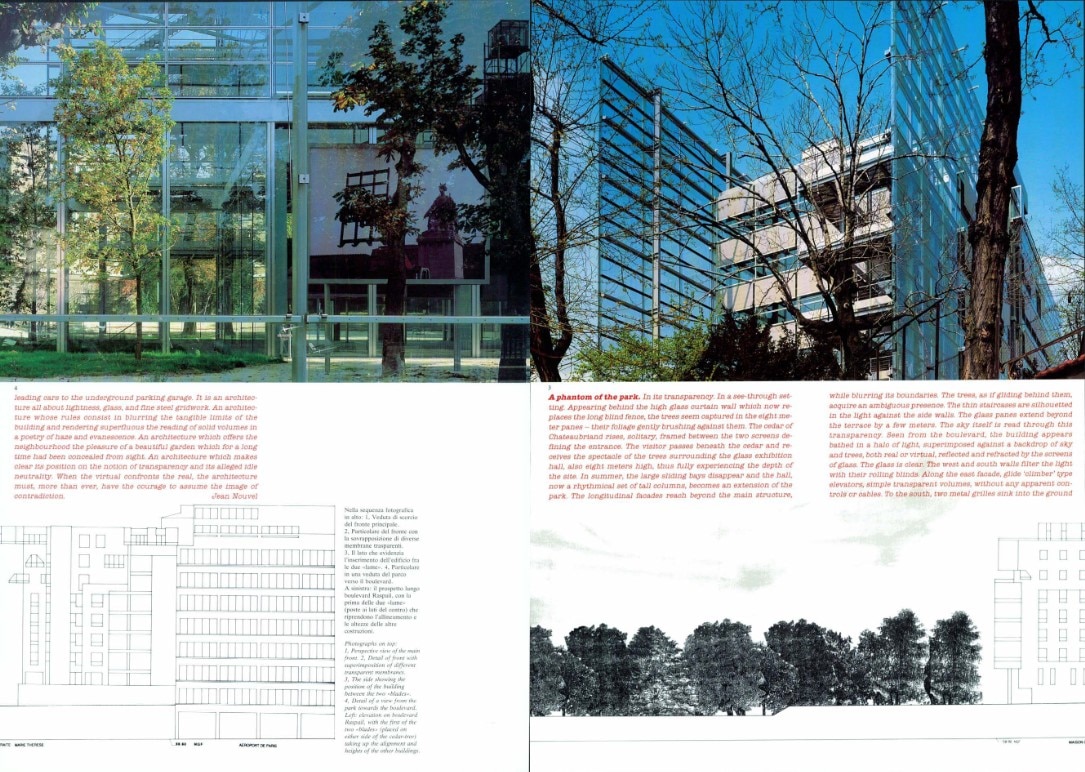

28

Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporaine

Paris, France, 1994

Domus 766, December 1994

There are architects who have looked towards the utopia of a dematerialized architecture, and among them could be Jean Nouvel, who with this building created a ‘ghost in the park.’ Behind a fence of tall glass facades resembling large urban stage sets, trees and lush flora appear, transpire, and reflect, surrounding, protecting, and integrating a compact building mass made instead of pure technology. The regular and thin steel structure and the total glass cladding give lightness to the building and make the tangible boundaries of the exterior blurred and evanescent. The double-height exhibition hall on the ground floor is transparent, openable, flooded with light, and the external vegetation of the garden provides a natural backdrop for each work that is welcomed and staged. On the upper floors, offices dedicated to the foundation’s extensive research and promotion activities for the world of contemporary art are developed and distributed, and even here Nouvel wanted to create environments where the internal-external relationship is immediate.

- Project:

- Jean Nouvel

29

Beyeler Foundation

Riehen, Switzerland, 1997

Domus 798, November 1997

View gallery

View gallery

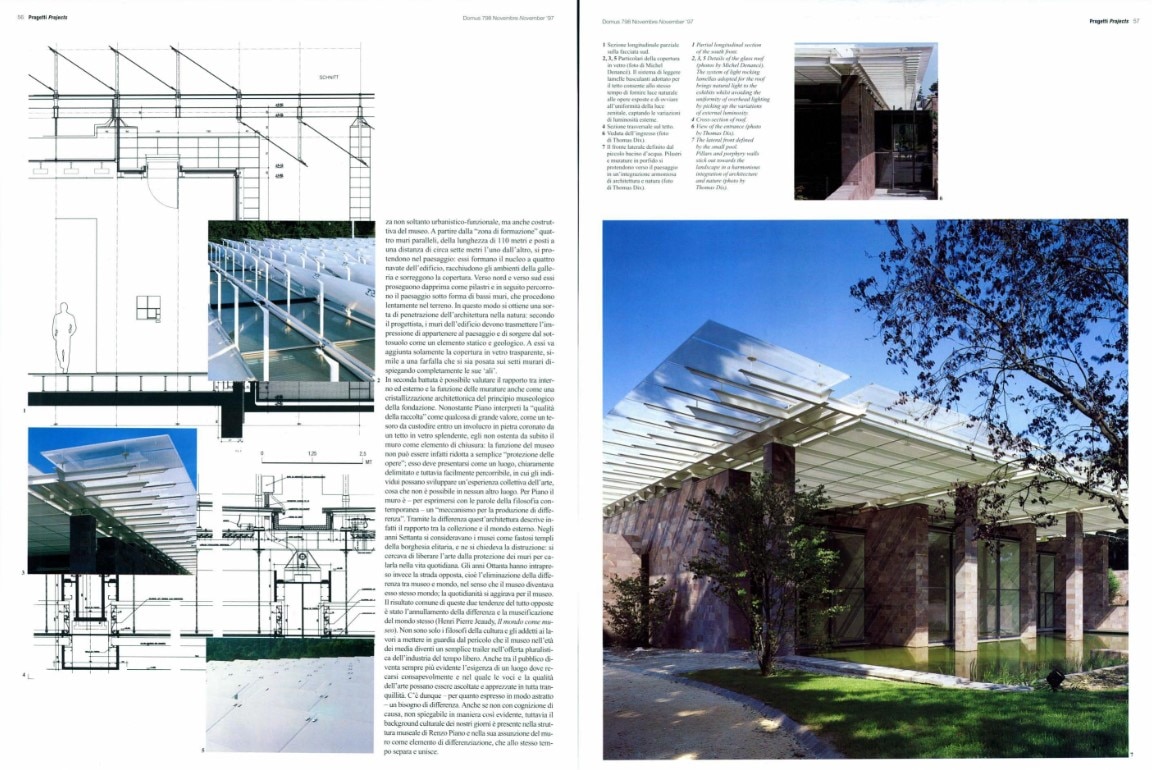

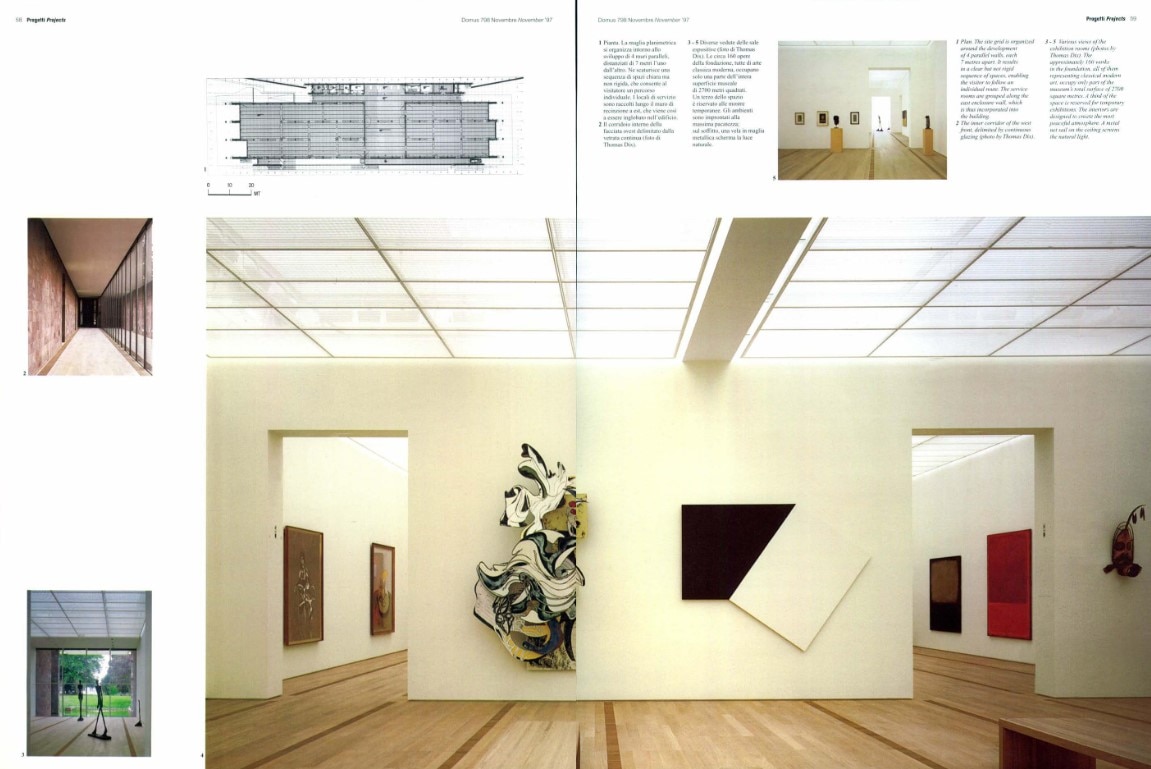

Commissioned by Ernst Beyeler for an architecture that would both protect and make public one of the most important private collections of modern art, Renzo Piano undertook a highly sophisticated task of determining the primary spatial qualities linked to the viewing of artworks, with the most natural light possible. He designed a ‘closed box’ with a glass lid, in which the most harmonious relationship between nature, space, light, and art is created. On a narrow and elongated lot, on the edge of a fenced park, the architect typologically worked on the enclosing wall, dividing and multiplying it to articulate the spaces: the typical ‘mechanism for the production of difference’ instead becomes the place of equality, of community, for a collective experience of art. Long walls of red stone typical of the region thus determine three parallel but interspersed naves, a free and protected path, occasionally open to the landscape, as in the winter garden to the west, overlooking the fields and created as a moment of relaxation for visitors. Between the busy roadside on one side and the quiet garden on the other, the museum has at its ends two bodies of water, which reflect the warm and direct light from the south and the cold and indirect light from the north. The work on light remains crucial inside, where Piano created a real canopy that – like treetops in nature – through a technology that adaptively mitigates solar radiation by filtering it, consistently ensures the highest quality visual experience of the artworks.

- Project:

- Renzo Piano (RPBW Architects)

30

Palais de Tokyo

Paris, France, 2002

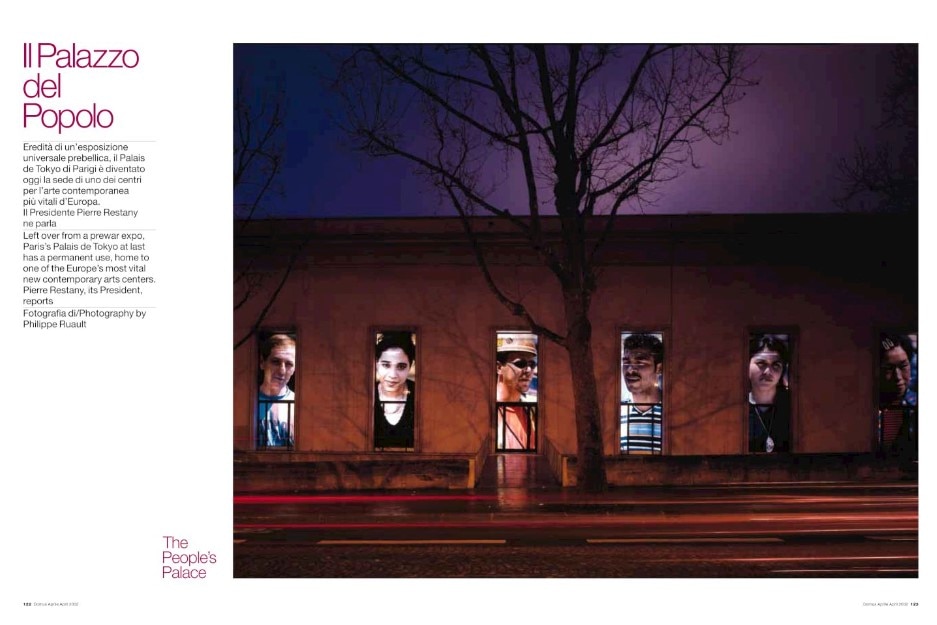

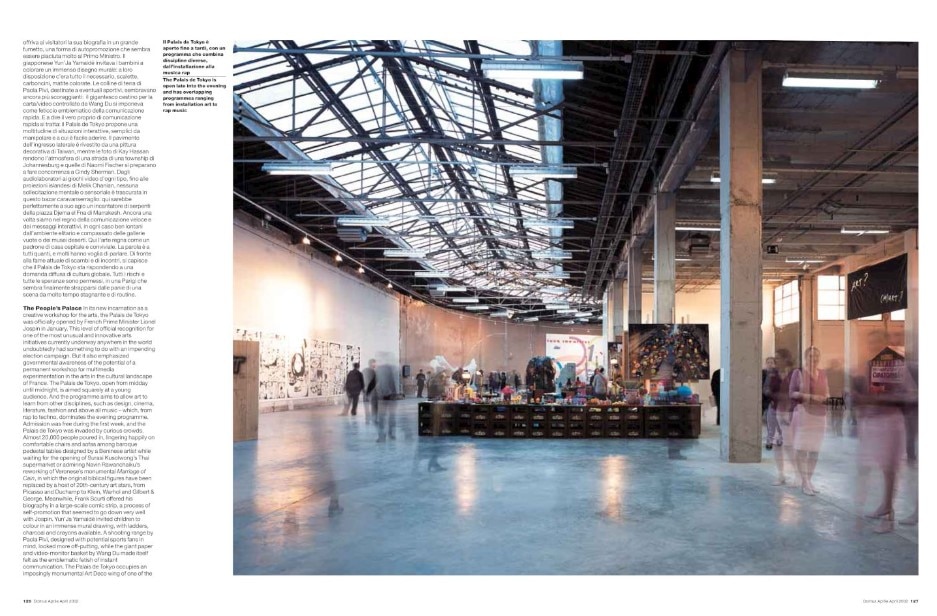

Domus 847, April 2002

Manifesting an innovative and highly topical attitude that Lacaton & Vassal first introduced in the early ‘90s, namely that of the recovery and ‘economic and social’ enhancement of built and renovated architecture, the project unfolds within a relic of the 1937 World’s Fair, with a late Art Deco monumental language, which had been reused and abandoned multiple times, always for artistic purposes. What remained was an architectural container intact on the edges but with a fragmented, layered interior full of superimpositions: with a new idea of ‘light post-production’ that enhances the existing with all its apparent defects, and programmatically using the language of the unfinished – aided by a very limited budget – Lacaton & Vassal created a space that continuously renews and progressively transforms from its inauguration in 2002 to its actual completion in 2012. A minimal intervention to urgently restore to the city an informal, flexible container, a true center for the creation of contemporary art where the artistic process is exhibited, almost in real-time, more than the product, and the investigation into contemporary art in relation to other disciplines. Presided over from the beginning by the critic Pierre Restany – well-known in Domus – this new museum immediately sought to position itself away from traditional elitist circles, as a space to ‘provide an answer to the desire for exchanges and encounters’ of the new generations.

- Project:

- Lacaton & Vassal

- Project of the restaurant:

- Lina Ghotmeh

31

Stapferhaus

Lenzburg, Switzerland, 2018

Domus, February 2024

View gallery

View gallery

Stapferhaus stands out as one of the most compelling contemporary museums for its cultural and exhibition program, which aims to address current issues while actively engaging the general public. Originally founded as a cultural center in the 1960s, the Stapferhaus finally found its permanent home in 2019 in a purpose-built structure designed by Zurich-based Pool Architects, winners of an international competition. The architectural layout seamlessly aligns with the research-driven approach of the management team. Comprising three distinct volumes of different sizes and functions, all united by a striking black timber structure and cladding, the museum embodies a modern aesthetic. A prominent open-air pergola defines the reception area, while an adjacent access tower houses essential facilities such as the ticket office, cafeteria, bookstore, and offices. At the rear, the largest volume serves as the exhibition area, spanning two floors with the flexibility to reconfigure staircases, partitions, windows, and passageways according to the needs of each exhibition. In this new museum, the traditional roles of curating, organizing, and staging are complemented by the incorporation of dramaturgy – a discipline aimed at fostering maximum public participation.

- Project:

- Pool Architekten

32

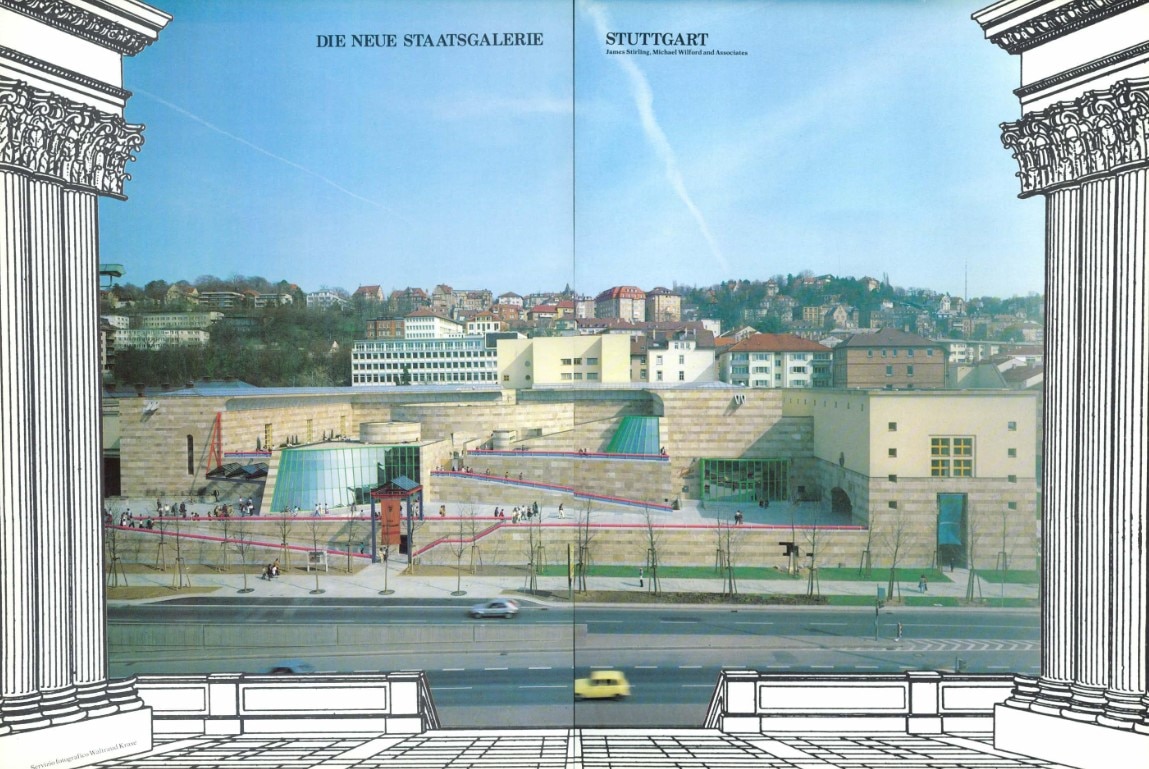

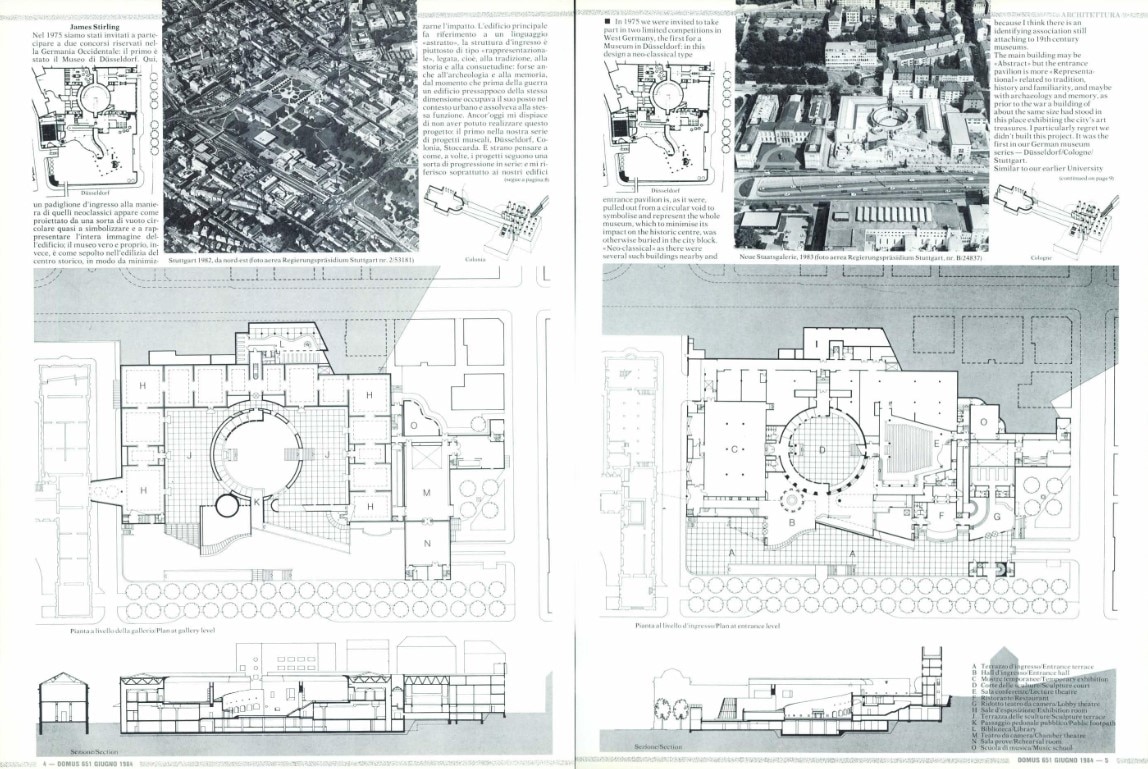

Neue Staatsgalerie

Stuttgart, Germany, 1984

Domus 651, June 1984

View gallery

View gallery

The Neue Staatsgalerie, designed by James Stirling, is a prime example of the era in which museums began to transform themselves into vibrant urban complexes, rejuvenating city areas as cultural and social hubs. Described as postmodern, its architectural language reflects a nuanced understanding of the complexities absorbed by society and the historic architectural milieu it inhabits, particularly in a city heavily scarred by the ravages of World War II. Located adjacent to the old neoclassical museum, built in 1837, the new gallery adopts its U-shaped layout while introducing a compelling new façade configuration. This is achieved through a series of multi-level pedestrian walkways that create a new relationship with the cityscape. The interplay of expansive, long stone ashlar walls with colored metal structures delineating passageways and entrances gives the exterior a sense of dynamism and approachability. With the Neue Staatsgalerie, Stirling sought to assert his active participation in a new architectural epoch – one that marked the end of a period rooted in the Modern Movement. This vision transcends stylistic boundaries and embraces a synthesis of diverse architectural languages: “In addition to Representational and Abstract, this large complex, I hope, supports the Monumental and Informal; and the Traditional and High Tech”.

- Project:

- James Stirling

33

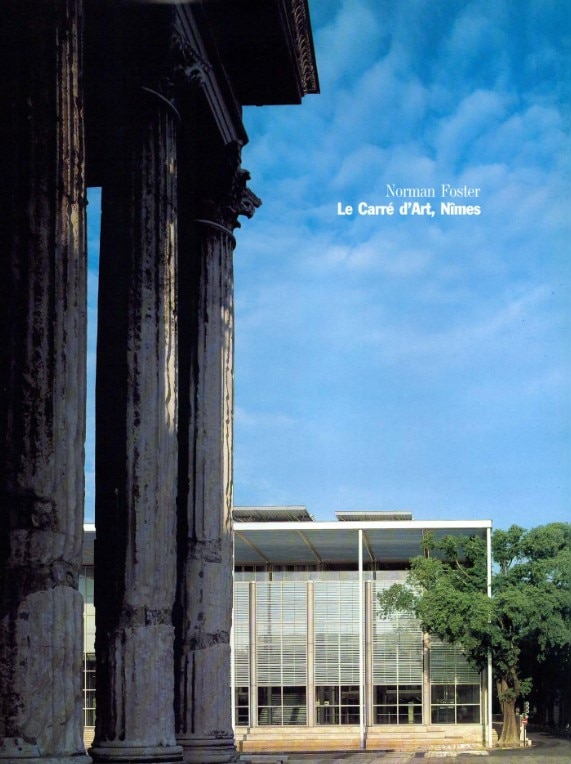

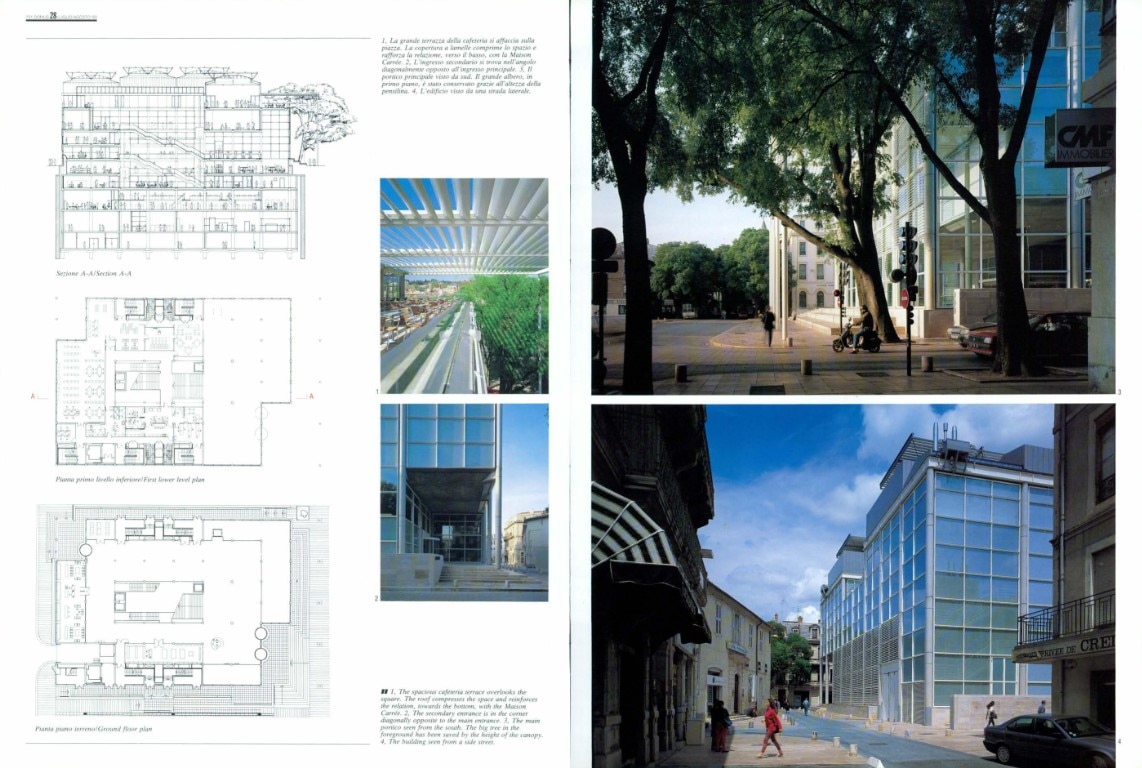

Le Carré d’Art

Nîmes, France, 1992

Domus 751, July 1993

In designing Le Carré d’Art, Norman Foster faced a significant challenge: to seamlessly integrate the new with the old, while creating an architecture that captured the spirit of its time. The building ingeniously combines the quintessential typology of a 1980s media library – traditionally housing books, magazines, audio and video documents – with contemporary visual, pictorial and sculptural art. Situated on the site of a demolished neoclassical theater in the heart of Nîmes, directly opposite the perfectly preserved Roman temple of Maison Carrée, Foster envisioned Le Carré d’Art as a multipurpose structure that would cater to the influx of tourists seeking cultural enrichment and a vantage point to observe and appreciate the transitions between epochs. The building, which blends harmoniously into its urban environment, has a façade of slender columns supporting a cantilevered roof that extends deep into the basement. Inside, a grand central “cascading” staircase provides access to a spacious atrium lit by a glazed roof that allows natural light to penetrate the lower levels. The library, archives and cinema are located here, while reception areas occupy the ground floor. Above ground, the art galleries beckon visitors, culminating in a refreshment area with a panoramic covered terrace offering sweeping views of the adjacent public pedestrian plaza and the temple – the heart of the ensemble.

- Project:

- Norman Foster (Foster + Partners)

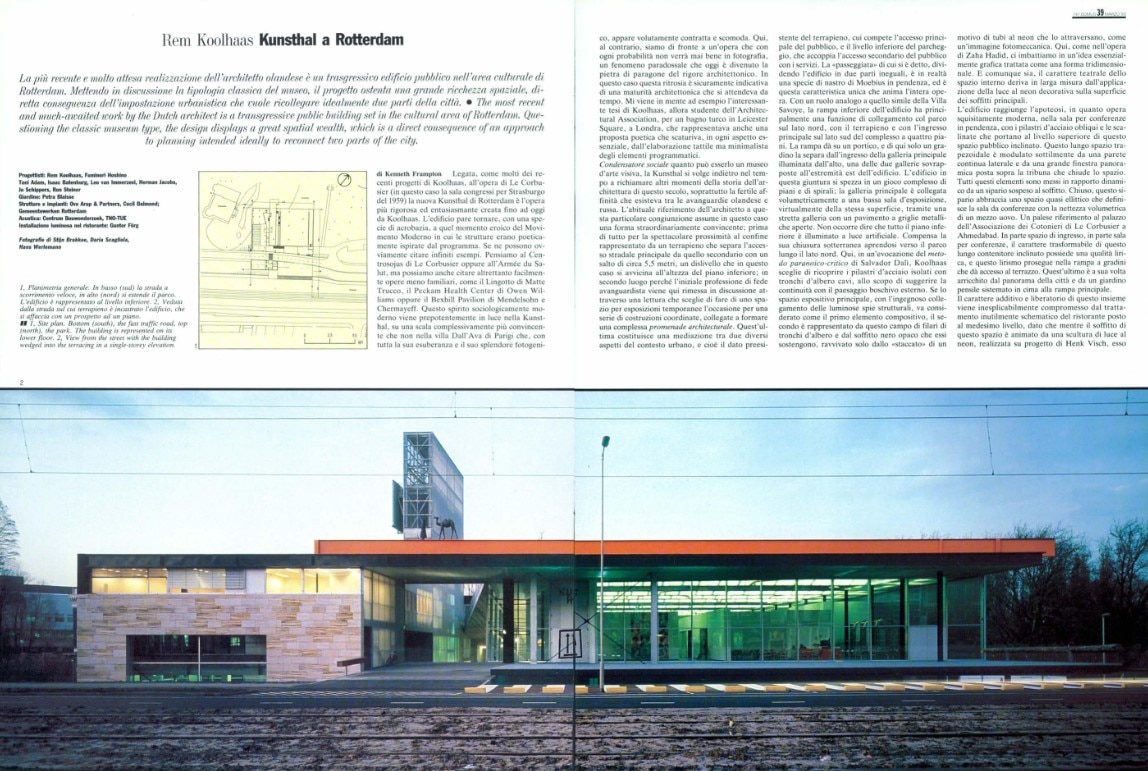

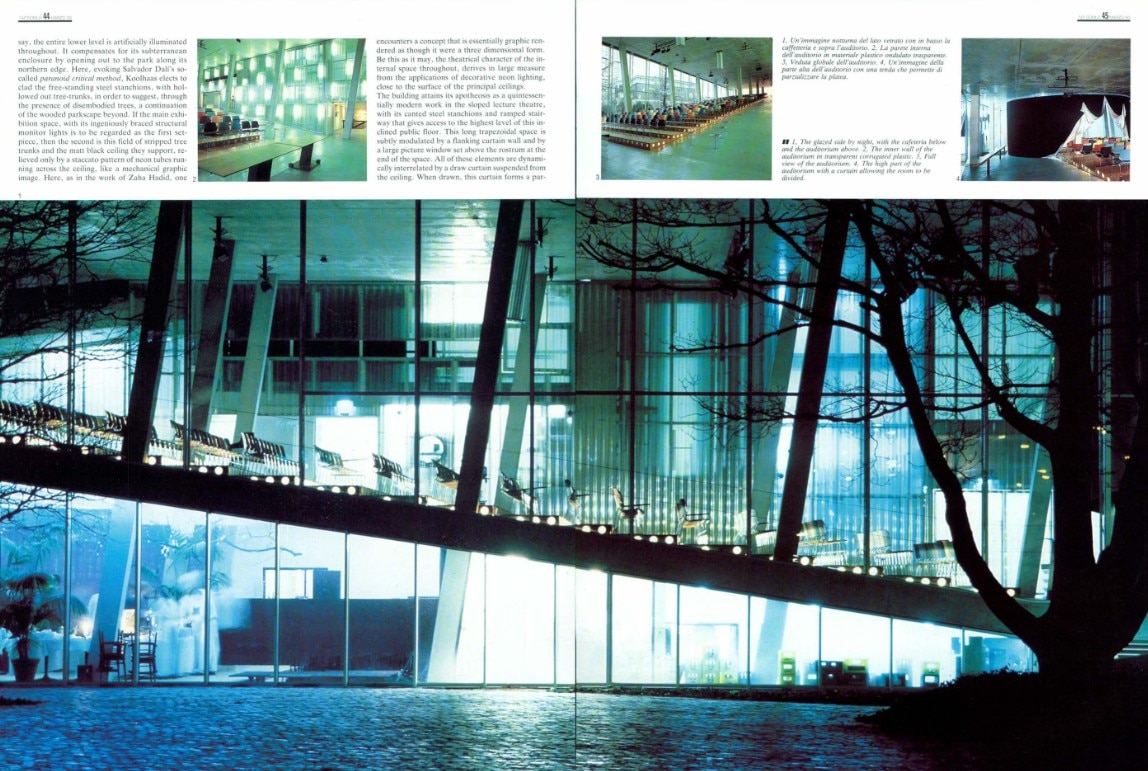

34

Kunsthal

Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1992

Domus 747, March 1993

The Kunsthal embodies Rem Koolhaas’s signature approach – a blend of intellectually cultured innovation and architectural provocation that challenges traditional museum typologies. It presents itself as a multifaceted organism with aspirations beyond mere structural boundaries, embracing a broader urbanist vision of the interrelationships within the city. Located at the intersection of a busy thoroughfare and Rotterdam’s Museum Park, the Kunsthal’s architecture facilitates a seamless integration with its urban surroundings. Inclined planes and ramps traverse the building, serving as a declared promenade architecturale, mediating between gradients and elevation changes. The intricately woven planes and spaces, conceived with structures “poetically inspired by their programmes”, house a range of amenities including an auditorium, a restaurant, and over three thousand square meters of exhibition space that includes both expansive halls and intimate galleries. In his introduction to the work in Domus, Kenneth Frampton highlights two particular features: an “ambiguous tectonic” resulting from the use of various cladding materials – from natural to man-made – integrated with non-orthogonal structures, and the development of a “a concept that is essentially graphic rendered as though it were a three dimensional form”. Designed to function as a social condenser, the Kunsthal exudes a theatrical essence, characterized by fixed and mobile wings, unexpected encounters along its paths, and moments of dialogue between interior and exterior spaces.

- Project:

- Rem Koolhaas, Fuminori Hoshino (OMA)

35

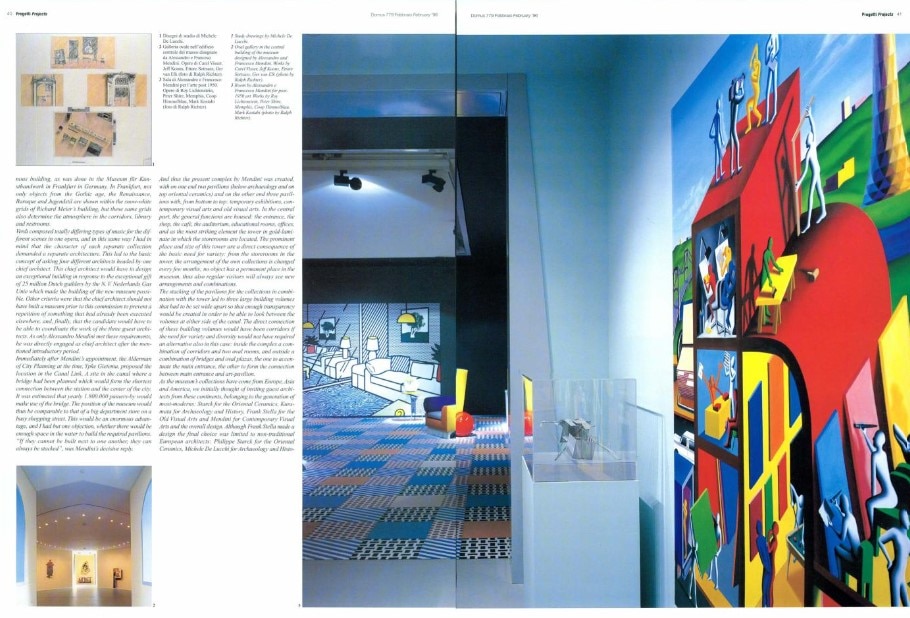

Groninger Museum

Groningen, The Netherlands, 1994

Domus 721, November 1990

Alessandro Mendini, together with his brother Francesco and Alchimia, returns to public architecture after years of absence with an intervention of rare linguistic, spatial and cultural complexity. Located on a canal as a new artificial island with two pedestrian bridges connecting the city center to the train station, the museum is conceived by Mendini as “a small, gentle Art Acropolis or Ark for art”. The project immediately attracted the talents of other architects, each of whom was assigned an independent pavilion. Michele De Lucchi, Philippe Starck, and Coop Himmelb(l)au were among those invited to contribute, each designing a fragment of the museum dedicated to different sections: archaeology and history, applied and decorative arts, and modern and contemporary art. Acting as a director overseeing the project, Mendini defined the common spaces and personally designed the striking golden entrance tower, which serves as both an archive and a repository for the artworks. Rooted in the postmodern concepts of complexity and patchwork, cherished by Mendini, the museum is conceived as an “interference between cathedral, stage, and home”. Within its walls, different environments aim to present artworks in active, non-neutral spaces designed to arouse curiosity and capture attention. Meanwhile, the exterior of each pavilion has its own visual identity, corresponding to the different cultural areas represented inside. For the 2010 renovation, Mendini was once again called upon to oversee the project, enlisting the talents of three contemporary designers – Maarten Baas, Studio Job and Jaime Hayon – to develop the restaurant, lounge area and information center.

- Project:

- Alessandro and Francesco Mendini, Alchimia with Philipe Starck, Michele de Lucchi, Coop Himmelb(l)au

- Renovation:

- Maarten Baas, Studio Job, Jaime Hayon

36

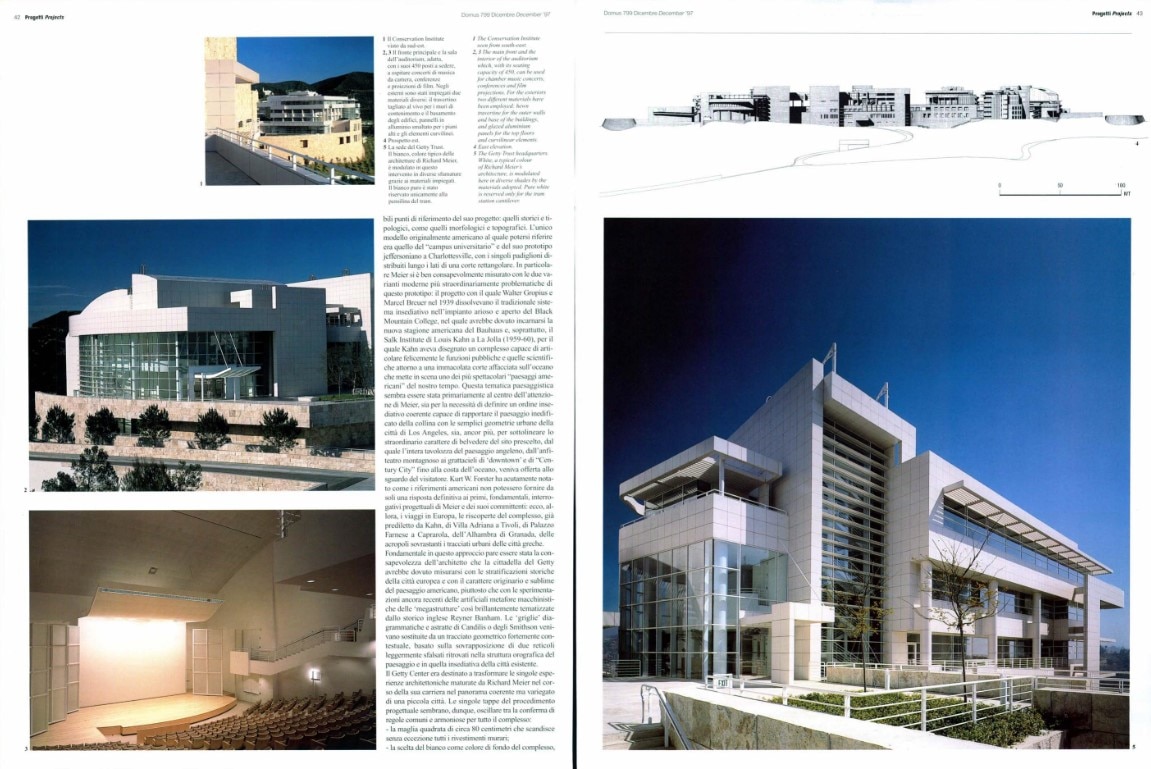

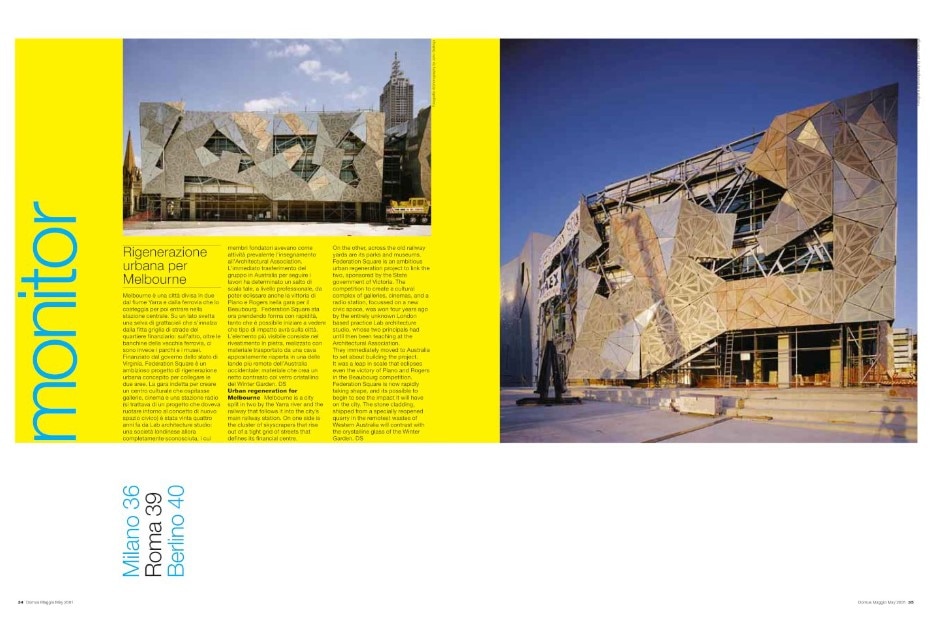

Getty Center

Los Angeles, USA, 1997

Domus 799, December 1997

View gallery

View gallery

Richard Meier had dedicated himself multiple times to designing innovative museums around the world, from Atlanta to Frankfurt to Barcelona, but the Getty Center can be considered his masterpiece, both in terms of scale and attractiveness. A true citadel of art, a contemporary acropolis atop a hill south of Los Angeles, from overlooking downtown on the horizon and the vast ocean beside it. It is reachable with a dedicated rail shuttle, silently winding from the valley floor to the threshold of the entrance level. Meier was commissioned to design a place to house the private and philanthropic program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, one of the most grandiose ever organized in history, dedicated to the acquisition, conservation, and promotion of the cultures of the arts. In this secluded and monumental location, a series of morphological references was transformed into grids, arranging pavilions of equal height to create a true small urban enclave with its squares, connecting pathways, and a seamless flow between outdoor and indoor spaces, amidst gardens, staircases, shaded courtyards, and sunlit areas. White prevails, as the architect's signature chromatic language, while cubic and cylindrical structures alternate with bases and grids, providing visitors with a complete immersive experience.

- Project:

- Richard Meier

37

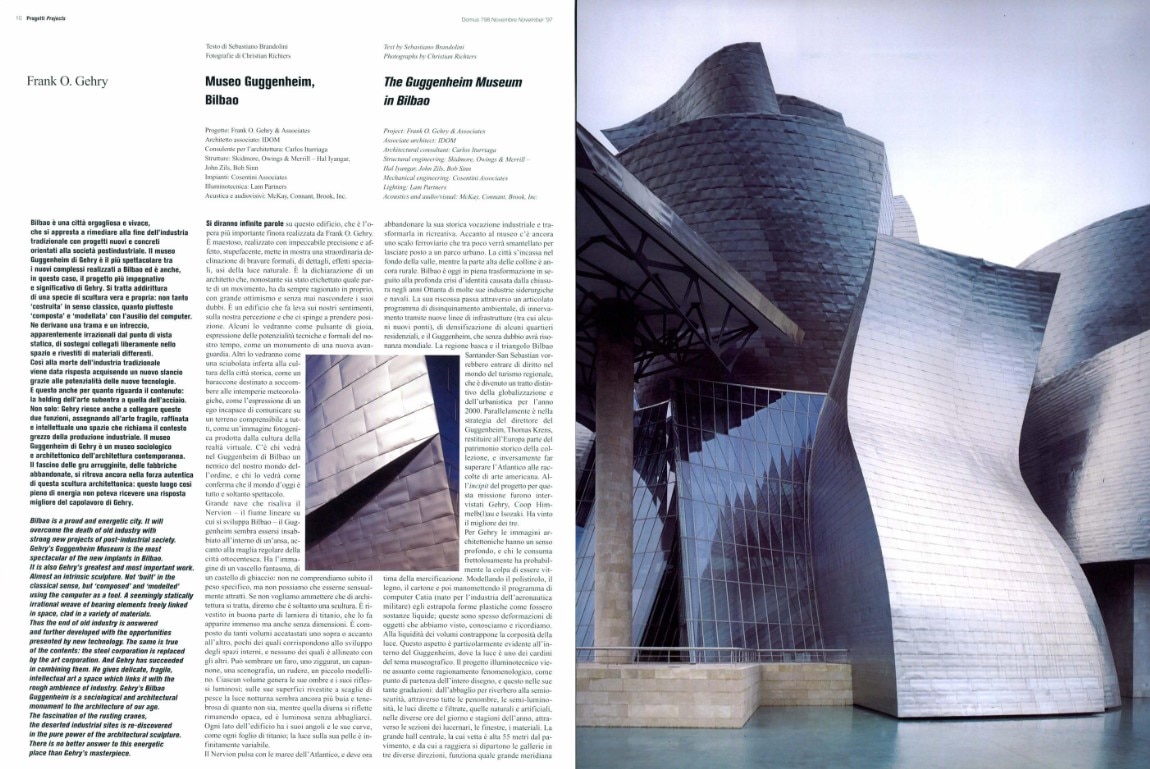

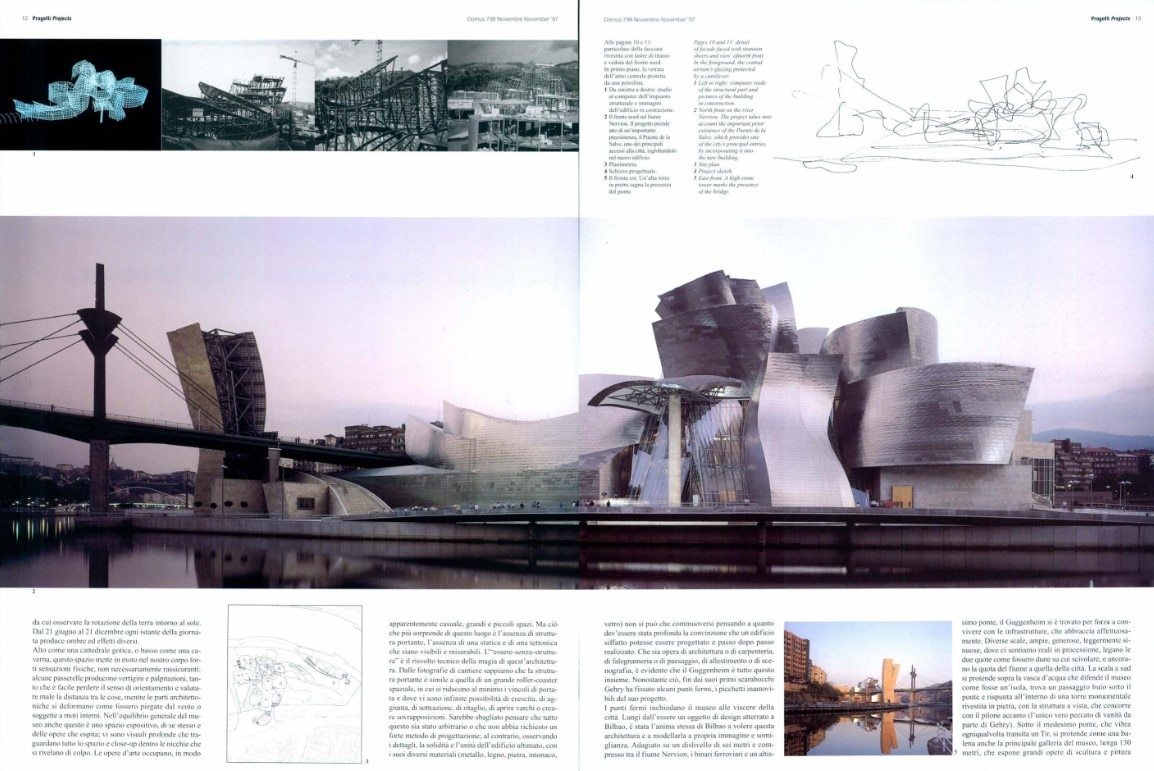

Guggenheim Museum

Bilbao, Spain, 1997

Domus 798, November 1997

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao by Frank Gehry was a turning point in contemporary architecture. The monumental building played an avant-garde role in the redevelopment of a former industrial part of the city and its attractive public image, an architectural sculpture to inhabit, was shaped through the use of new computer technologies. Years after his first museum intervention for the Vitra Design Museum, Gehry found a compositional, structural, and material maturity, that propelled him towards numerous other iconic projects. It is also worth noting that the foundation behind this project is the same as the one behind the museum in New York. This marks the beginning of a global initiative to extend its influence and promote the associated cultural values of art. Located on the banks of the city's river, near a bridge connecting the city center, this building both conforms to and deviates from the Postmodernist architectural culture, leaving behind the lightness of future morphological fantasy inspired by Deconstructivism principles, now attainable through innovative construction techniques and technologies. The success of this museum, drawing millions of tourists (and sparking critical debates on the role architecture should play in serving the art it showcases), has given rise to the concept known as the “Bilbao effect.” This term is frequently employed in urban discussions to describe the allure of an architectural endeavor in redeveloping an urban area.

- Project:

- Frank Gehry

38

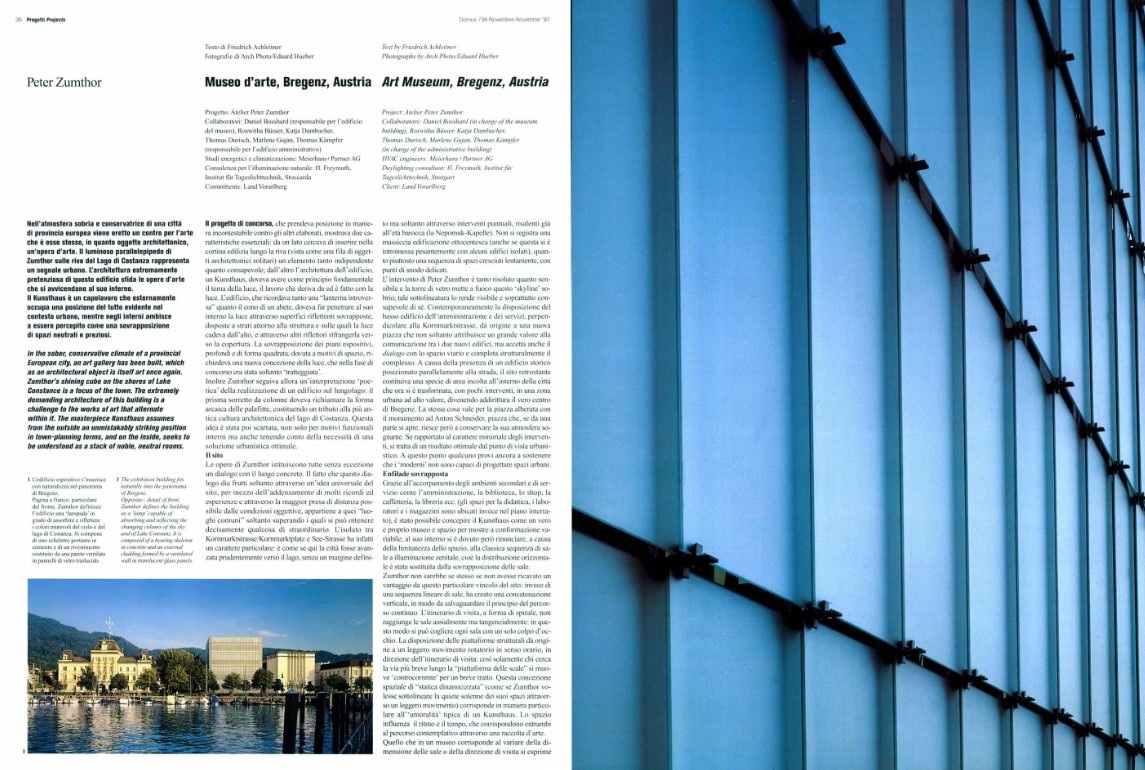

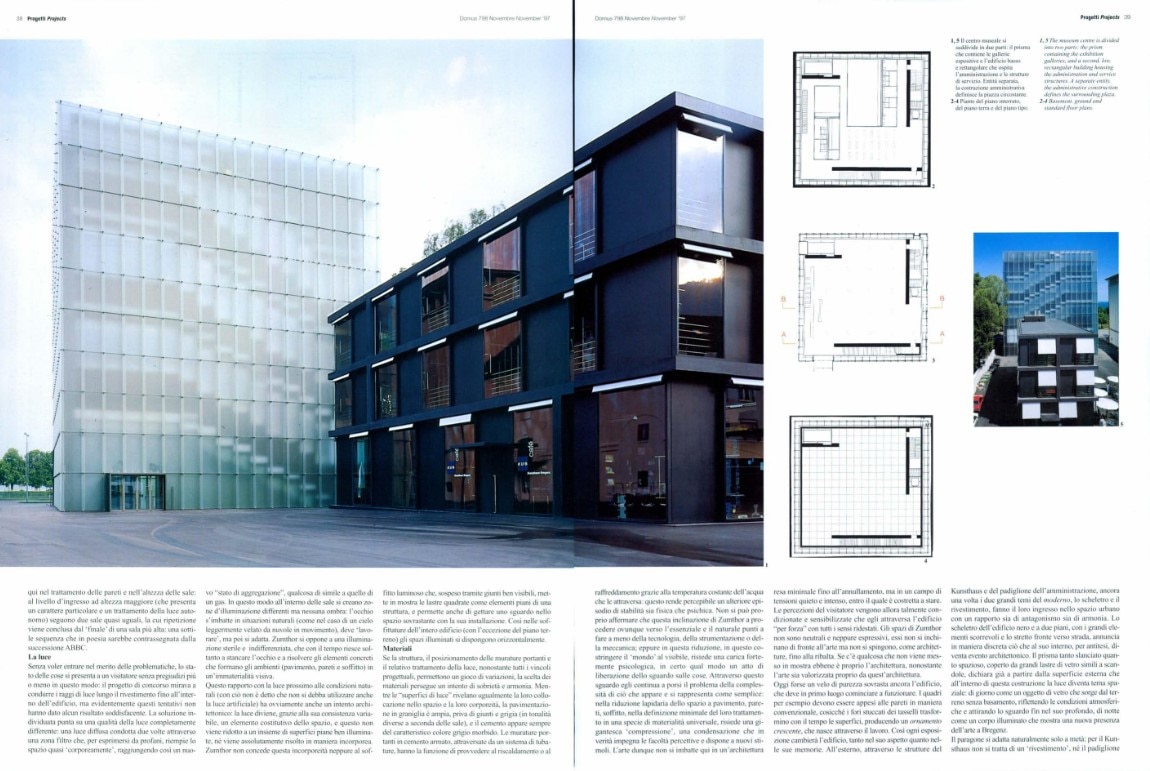

Kunsthaus

Bregenz, Austria, 1997

Domus 798, November 1997

View gallery

View gallery

Peter Zumthor has accustomed his audience to anticipate architectural works that are both rigorous and marvelous, seemingly crafted with minimal elements yet capable of expressing themselves to the fullest. The Kunsthaus in Bregenz epitomizes architecture designed for light and with light, serving as the true key concept for a visual art museum. Through a clever system of interstices, light floods in from all directions, penetrating horizontally to illuminate the ceilings of various single-room spaces that lack openings and are stacked to form a glass tower. The building’s core is made of reinforced concrete, while three detached orthogonal load-bearing walls conceal the elevators, creating a constant square space on each floor. The external facade is made of glass panels without frames, anchored with visible clamps and arranged like shingles. The result is a luminous parallelepiped, discreetly captivating from the outside – particularly at night when it emits a gentle glow – while remaining neutral and abstract on the inside to avoid interfering with the viewing and interpretation of artworks. Positioned just steps from the lakeshore, the cubic body of translucent glass stands in isolation, just like other historic buildings along the city’s coast. It pairs harmoniously with a smaller complementary structure housing a bookstore and café on the ground floor and administrative offices on the upper levels. This arrangement and integration create a new square, belonging to the new museum and mediating between the lakeshore and the historic center.

- Project:

- Peter Zumthor

39

Moderna Museet

Stockholm, Sweden, 1998

Domus 806, July 1998

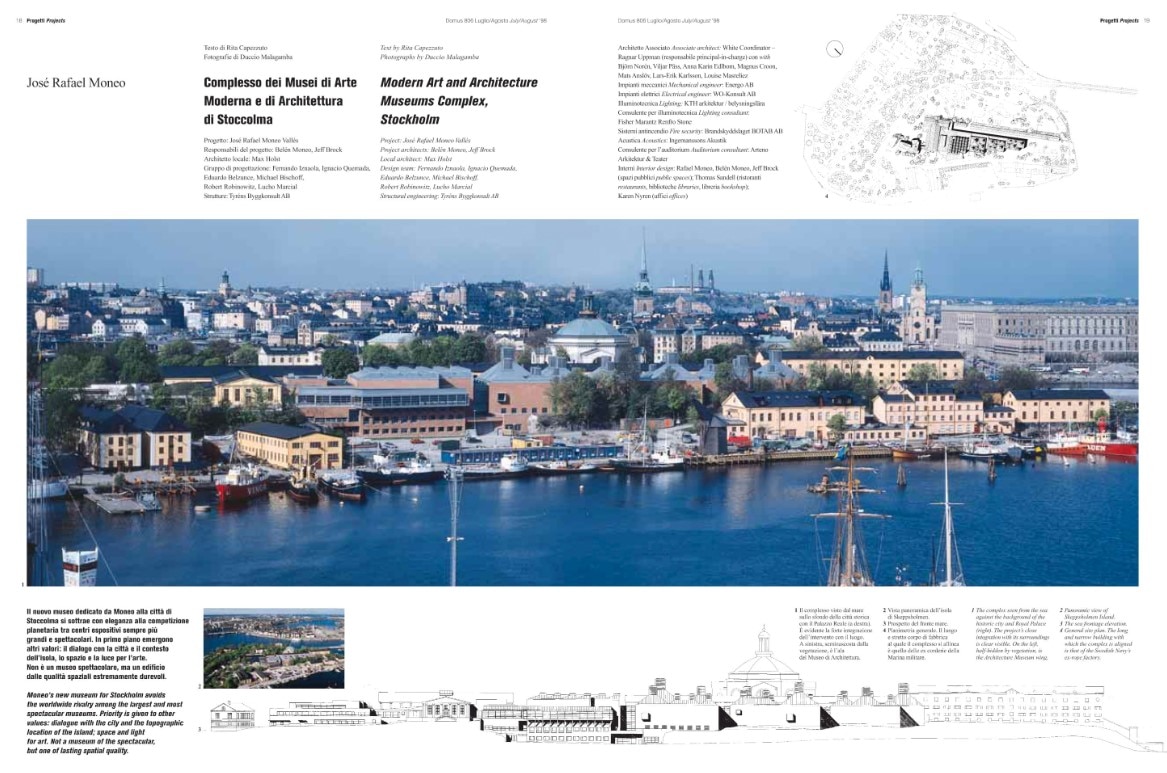

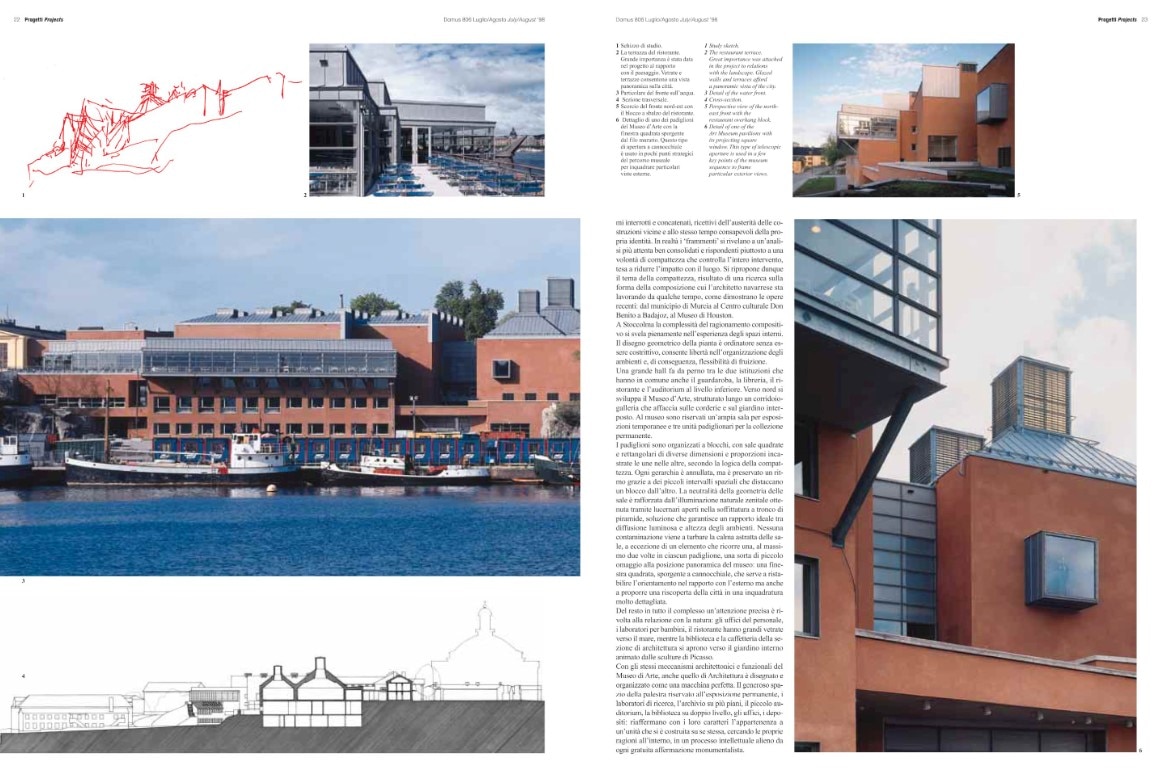

Against the spectacle of museum architecture, for this complex Rafael Moneo proposes discreet and practical language, yet not devoid of poetry. The main body comprises the art museum, the Moderna Museet, for which Moneo carefully considered the diverse visual impact between arrival by land – along the bridge to the island where the complex sits, where the museum blends seamlessly into nature and the surrounding architecture, almost imperceptible – and arrival by sea, where the continuous facade with its characteristic covering is immediately apparent. The architectural ensemble is distinguished by its red color and the distinctive pavilions clustered in blocks. The pavilions, primarily closed on the exterior, feature occasional square openings that protrude, serving as guides along the path and providing moments of respite with panoramic views of the landscape. Atop the truncated pyramid roofs, numerous cubic lanterns multiply, pouring natural light into the rooms. Despite their rigorous geometric design, these spaces are not restrictive; instead, they facilitate a free organization of usable and flexible spaces. The museum of architecture, now known as ArkDes, was built later as an independent and diverse entity, seamlessly integrating with some pre-existing structures and sharing certain functions with the art museum.

- Project:

- Rafael Moneo

40

Kiasma Museum

Helsinki, Finland, 1998

Domus 810, December 1998

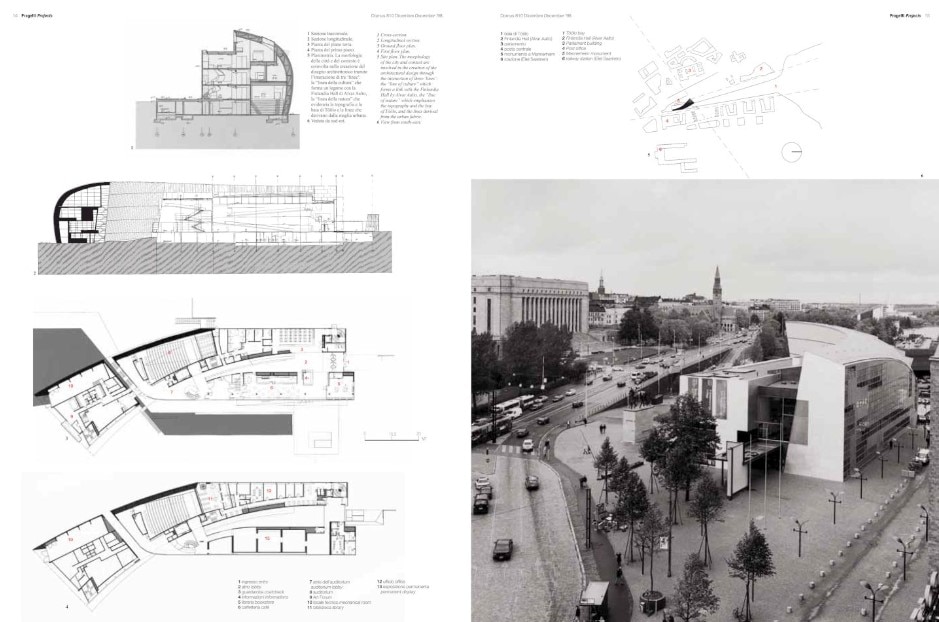

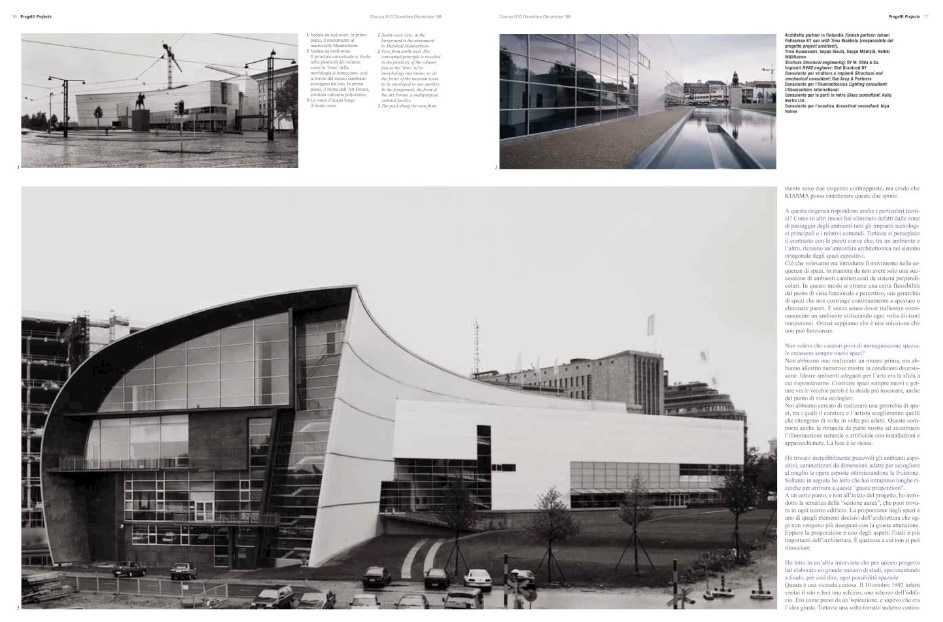

Kiasma is the first museum designed by Steven Holl, who, up to that point, had only completed a few projects while running a small studio akin to an atelier for conceptual designs and fresh architectural concepts. The project won the selection competition by providing the best in addressing both urban planning and museographic challenges concurrently. The building aimed to serve as a catalyst for a new urban configuration, fostering increased foot traffic while providing serene and well-illuminated environments for direct art experiences. Light plays a crucial role in this architecture, particularly given Helsinki’s unique light conditions, which are never constant due to continuous meteorological shifts and are notably horizontal due to its high latitude. The interplay of reflections is often viewed as a means of indirectly guiding natural light. The name “Kiasma” (chiasm) derives from an etymology suggesting interweaving, a motif frequently accentuated in the museum’s design. This is evident both in the external shape, which results from a sophisticated analysis of directional elements harmoniously integrating with urban and human scales, finding a balance among space, artwork, and observer, and in the internal spaces, articulated between orthogonal and curvilinear walls, ramps, and stairs, juxtaposing solid masses with ethereal atmospheres.

- Project:

- Steven Holl (Steven Holl Architects)

41

Tate Modern

London, United Kingdom, 2000

Domus 828, July 2000

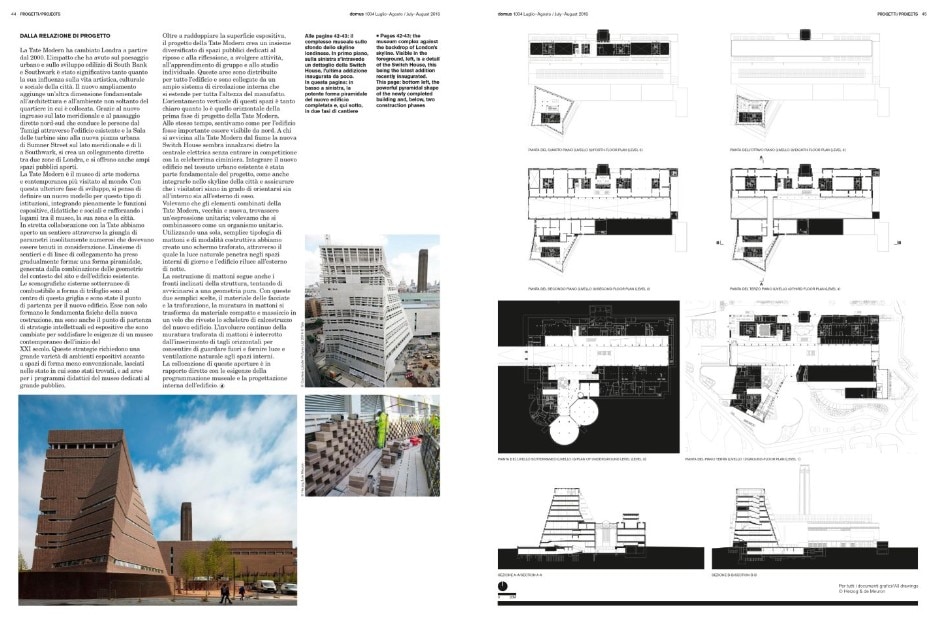

Tate Modern is a landmark in contemporary museography, celebrated for its imposing physical scale and the innovative vision that transformed an abandoned industrial site into a vibrant cultural hub at the turn of the millennium. Beyond its architectural significance, Tate Modern is hailed for its role in urban regeneration and social cohesion, and is the world’s most visited museum of modern and contemporary art.

Herzog & de Meuron’s redevelopment of the Bankside Power Station has cemented their status as leading architects of our time. Their approach to architecture is profound, seeing it as a “psychogram” of people, cities and cultures. Central to their design philosophy is the creation of welcoming spaces through a non-invasive approach. In addition to expanding the gallery space in the north aisle, the architecture incorporates distinctive white glass volumes that juxtapose with the massive red brick walls and identify new elements, including the prominent parallelepiped on the roof exterior and small light boxes within, creating intimate arched spaces that offer quiet moments of contemplation with privileged views of the artworks in the Turbine Hall. From inside the hall, they appear as ethereal bodies of light, seemingly suspended in mid-air.

In 2016, Tate Modern underwent a transformative extension to the south, doubling its gallery space and expanding its facilities for art reflection, public engagement, and education. Built on existing oil tanks, the new building’s design prioritizes vertical connections, with pathways and connecting lines gradually converging into a pyramidal volume known as the Switch House.

- Project:

- Herzog & de Meuron

- Renovation:

- Herzog & de Meuron

42

Museu de les Ciències

Valencia, Spain, 2000

Domus 830, July 2000

View gallery

View gallery

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

La Ciutat, Museu de les Ciències, Valencia, 2000

Courtesy Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

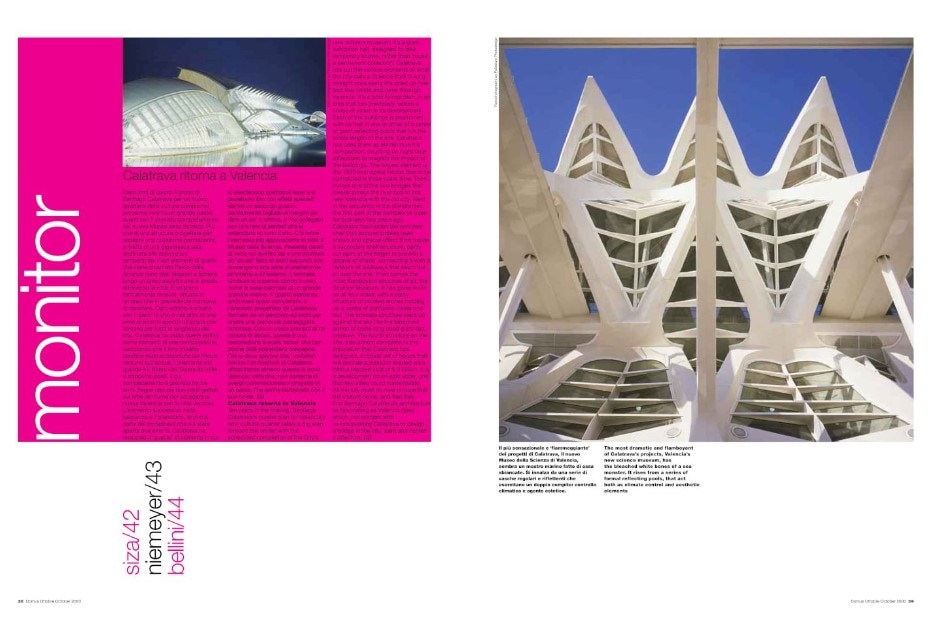

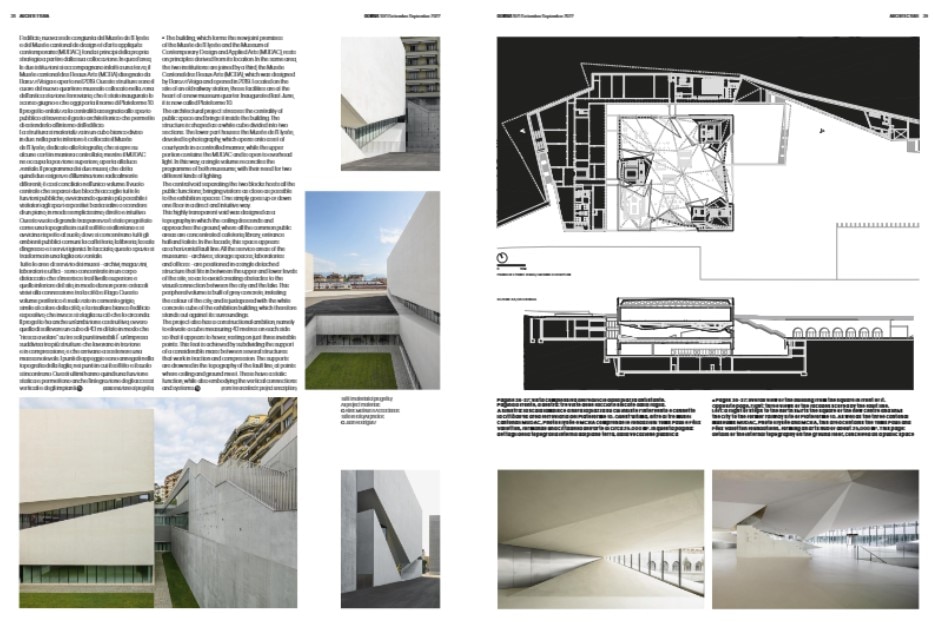

In the poetic vision of Santiago Calatrava, the presence of zoomorphic and organic forms has always represented a precise aesthetic pursuit, applied to the concept of architectural structure. Cement trees, forks, shells, vertebrae, joints, crests, eyes, pupils, and eyelids are just some of the references that can be recognized in the architect’s plastic work. For Valencia, his hometown, the designer created a monumental district of culture and science, arranging a series of pavilions and structures along the course of the city’s river, transformed into a long urban linear park. On a large flat surface defined by pools of water surrounding all the buildings arranged along an axis, the Museo de las Ciencias stands out as the main actor and perhaps the most spectacular in complexity and size. It is accompanied by a Planetarium (Hemisfèric) and a Theater (Les Arts), as well as a parallel service structure (Umbracle) containing underground parking and a linear elevated walkway shaded by vegetation, offering a panoramic view of the entire complex.

- Project:

- Santiago Calatrava

43

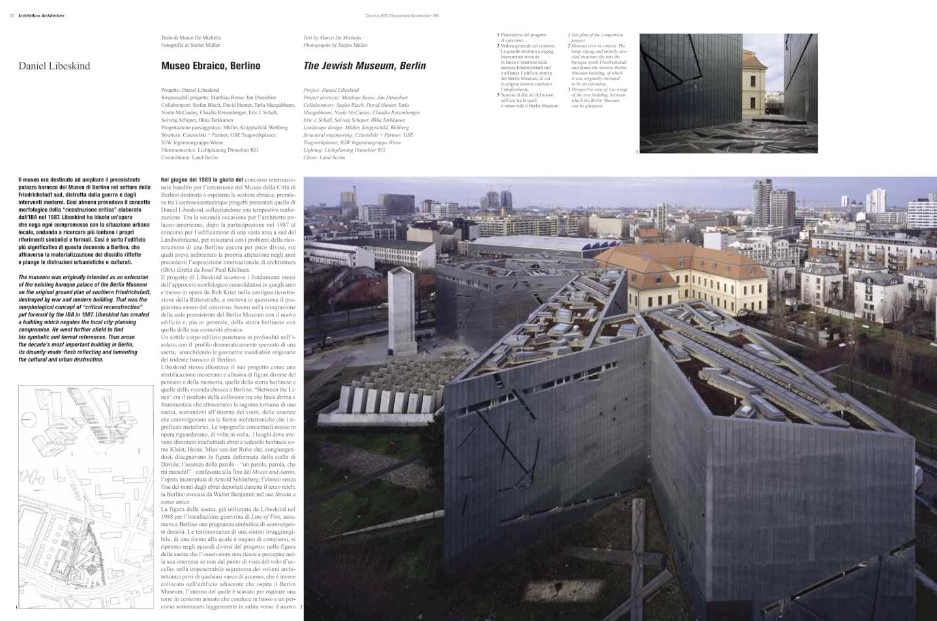

Jewish Museum Berlin

Berlin, Germany, 2001

Domus 820, October 1999