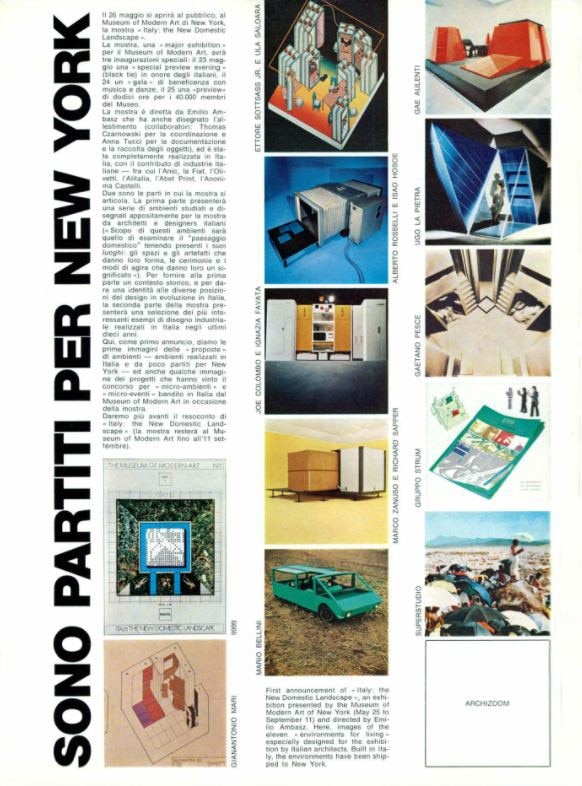

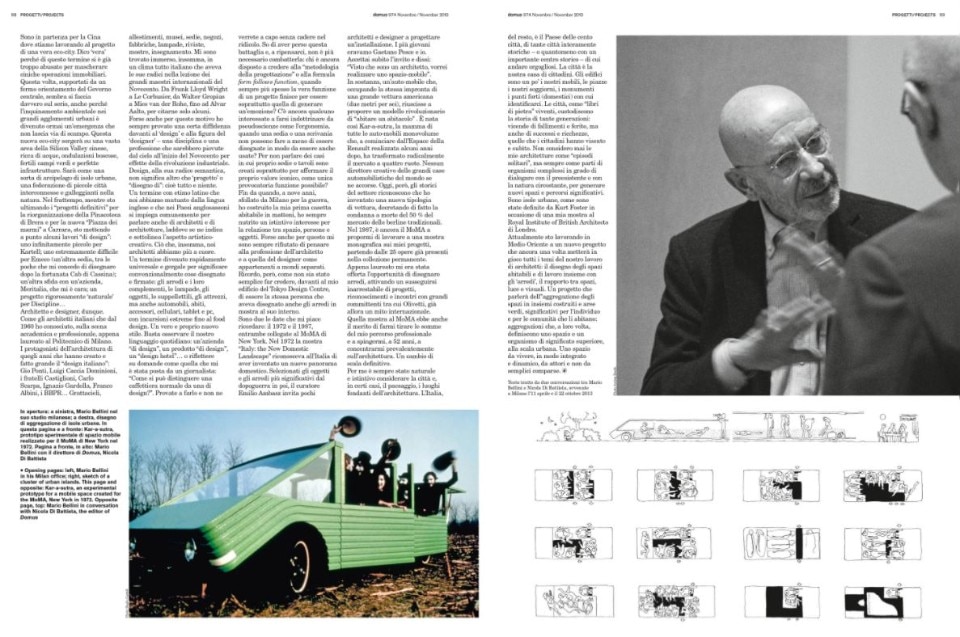

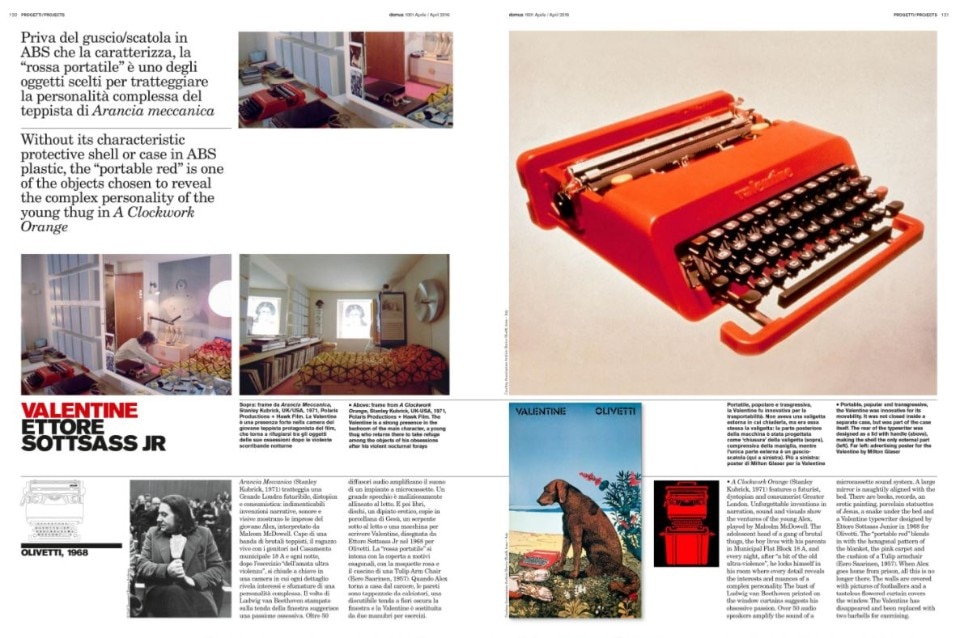

It has been exactly 50 years since one of the crucial moments in the history and international success of Italian design: the exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape”. Conceived, planned and organised by Emilio Ambasz with backing of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, the exhibition was on display at MoMA (New York) from 23 May to 11 September 1972. In fact, it was especially thanks to this exhibition that a country with a still weak and controversial modernity as Italy suddenly became the most advanced benchmark for an eminently modern discipline such as design. Therefore, it offered the world a model and a design method – even more than a production one – destined to be adopted and imitated over and over again at an international level.

The exhibition was organised in two sections: the first displayed 180 objects of Italian design, chosen from among the most representative of recent years (including the Soriana Armchair by Afra and Tobia Scarpa, produced by Cassina, the Mezzadro chair by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni for Zanotta, and several lamps by Flos and Artemide). The second section consisted of 12 installations specifically realised for the exhibition, aimed at focusing on housing proposals for the future. An additional part of the exhibition was dedicated to the winning projects of a competition open to Italian designers under 35 years old, promoted to allow the free expression of an idea, regardless of the possibility of relying on an industry to produce prototypes.

.JPG.foto.rmedium.jpg)

MoMA asked all the invited designers to work on a predefined design theme: the interior. The original and expressive solutions of the various designers are still striking today. For instance, Ettore Sottsass designed a mobile wardrobe, almost a shell on wheels, or an “equipped accordion”, which becomes a kitchen, a seat, a juke box, a toilet, a shower or a wardrobe, depending on how it is internally completed. This solution is based on a “mutant” design vision that makes traditional home spaces lose their meaning, but also makes furnishing elements lose their codified form, to adapt them all to the single modular form of the container.

On the other hand, Mario Bellini worked on the car’s interior, aiming at enhancing it as a place of relationship. The prototype of his Kar-a-sutra exhibited at MoMA not only frees the car’s interior from the constraint of fixed, pre-established positions, but inaugurates a design line that anticipates the design of MPVs by several years.

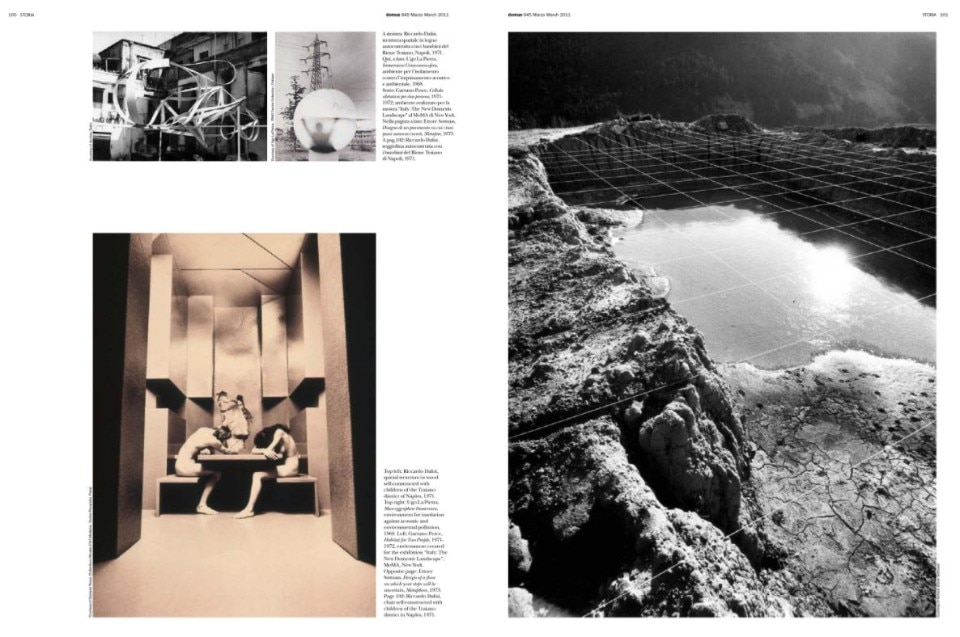

The other exhibited projects ranged from functionalist solutions by Zanuso and Sapper (with their mobile home project made up of large plastic capsules) to the apocalyptic and post-catastrophic visions of Gaetano Pesce (whose Habitat for two people, a fake archaeological find from the year 2000 rediscovered in good condition a millennium later, is a paradigmatic example of visionary design applied to the configuration of a space that seems suspended between Escher and Piranesi). From Joe Colombo’s science fiction approach to Ugo La Pietra’s multimedia and media approach. From Gae Aulenti’s modular pyramidal spaces to Alberto Rosselli’s mobile capsule that can be expanded in four directions. And so on to the more specifically political provocations of the Strum Group (which produced and presented a comic strip) and the radical and anti-establishment ones of Enzo Mari, who wrote a letter to the Exhibition managers.

On the other hand, the Archizoom Associati group proposed an empty, grey room in which the voice of a little girl described a large, bright, colourful house, just as any visitor could imagine it to be. The great theme of participation is thus faced, together with the utopia of direct involvement of the user/consumer in the realisation of the project.

In short, they all outline a “polycentric” panorama, as Emilio Ambasz rightly and acutely wrote in the introduction to the catalogue: but it is precisely this lack of homogeneity, this plurality of voices and methods, far from being a weakness of the Italian design, that ends up being its added value and strength, releasing creativity and innovative energy flows largely unknown to the design of geopolitical and economic areas that are much more modern than Italy was in the early 1970s.

In the USA, the exhibition was received very positively. However, it provoked controversial reactions in Italy. For instance, a debate published in the magazine Abitare (n. 107, July-August 1972) was mainly critical: some spoke of “the swan song of Italian design”, others provincially complained that the Italian design exhibited at MoMA had not been selected by Italians, while others raised more radical doubts about ideology and discipline.

The sociologist Francesco Alberoni, for example, in an article programmatically entitled Progetti per l’uomo immaginario, slams it as follows: “The overall impression (...) is that we are faced with a production, an offer (in economic terms) that has not been solicited by a real demand and that even struggles to imagine its own public consumer; of a theory unrelated to a practice, of a product that has neither marketing nor market”.

Such positions echo the old humanist prejudice against design, as well as the paleo-functionalist idea that design should simply be a tool for responding to needs and already obvious and mature social demands. The prophetic and far-sighted breath that emanates from the projects exhibited at MoMA escapes the debate in Italian magazines, along with the idea that design should not necessarily be functional only to the existing, but also to the possible, not only to the present, but also to the future.

In fact, one of the few true cultural (but also design and entrepreneurial) export policies that Italy was able to express in the second half of the 20th century was inspired by “Italy. The New Domestic Landscape”.

Opening image: View of the exhibition set-up “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape”, MoMA, NY, 26 May – 11 September 1972. Courtesy © 2022. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Firenze