The work of some architects is able to obtain worldwide resonance despite the fact that they operate almost exclusively in a single geographic context during their entire career. This is without any doubt the case of Carlo Scarpa: with the exception of some projects located in other Italian cities like Florence, Bologna or Palermo, most of his architectural production is concentrated in the Italian region of Veneto and its surrounding areas.

Born in 1906 in Venice, Scarpa studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and began collaborating with craftsmen and glassmakers in the Murano Island. In 1926 he obtained the qualification in Architectural Design and began collaborating with Guido Cirilli at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia (IUAV) as a teaching assistant. In the following years, his career proceeded on a double layer: the creation of furniture and domestic interiors and the collaboration with the glass factory of Paolo Venini, of which he became the artistic director.

Carlo Scarpa’s first significant architectural work was developed in 1935: it involved the renovation of some buildings of the Ca' Foscari University. The project, which Scarpa himself came back on in 1957 modifying it further, shows the architect’s great sensitivity for interventions in existing historical buildings. Demonstrating great attention to the relationship between the new materials introduced and the pre-existing ones in the Rectorate building and the Hall of Academic Acts, Scarpa thus began to define some principles that have manifested through numerous projects in his career: according to him, the project on the built heritage should have been faced with solutions that highlight the presence of a contemporary intervention but that at the same time are perfectly calibrated on the characteristics of the existing. Through the use of linear joints between different materials, engravings and metal elements in the furnishings (which contrast with the stone and brick) he managed establish a dialogue between the original language of the building and his personal spatial poetic.

A few years later, Scarpa was commissioned to renovate the exhibition layout of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and in the same period he started a collaboration with the Biennale, first designing the set-up of the Paul Klee exhibition (1948) and then the Book Pavilion (1952) located in the Giardini, which is strongly influenced by the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. The partnership with the Biennale continued over the years with other projects: the Garden of Sculptures in the central pavilion of the Giardini, characterized by a formal research that highlights the relationship between the structural role and the sinuosity of the concrete volumes that compose it; subsequently, Scarpa also designed the Venezuelan Pavilion of the Biennale.

Not limited only to the collaboration with the most famous Venetian cultural institution, the interest in museography and installations is constant in Scarpa’s production. Among the most important projects of the architect there are the National Gallery of Sicily in Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo (1953-1954), the extension of the Gipsoteca Canoviana in Possagno (1956-1957), the Querini Stampalia Foundation (1961-1965 ) in Venice and the restoration of the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona (1964). These projects have in common various elements that are expressed in different ways according to the characteristics of the pre-existing buildings: in addition to the aforementioned attention to the relationship between new and old, it is also possible to notice in-depth research at the architectural detail scale for the elements that make up the exhibition.

For Scarpa, the exhibition is a dialogue – in some cases linear, but more often made up of contrasts – between the works on display, the place that hosts them and the curatorial narrative. Each spatial element that is part of the permanent exhibition design is studied in detail and in relation not only to the artworks to be exhibited, but also to the others located in the same room and to the architectural context in which it is inserted: a relevant example is the pedestal of the equestrian statue of Cangrande della Scala, which consists of a reinforced concrete shelf that allow the spectator to observe the statue initially from below and then, following the visit path outlined by the system of metal walkways, from the front. The statue that dominates the viewer as he enters the museum thus becomes part – thanks to the exhibition set-up – of the narration of the history of the place.

Although the museums and installations are among the best known works in Scarpa’s production, those constitute only one part of the architect’s work. A series of interventions (in this case mainly new constructions) that show recurring themes in the different phases of the architect’s career are the villas. The Venetian villa, inevitably associated in the common imaginary to the houses in rural contexts that Andrea Palladio designed for the noble families of the Sixteenth century, came back to the scene after World War II, in particular thanks to the advent of a bourgeoisie enriched with commercial activities and industrial plants. Among the most important villas are Villa Zoppas in Conegliano (1953) and Villa Veritti in Udine (1955-1961), but the project that most fully demonstrates Scarpa’s ideas on this architectural typology is Villa Ottolenghi in Bardolino (1974- 1978). All the elements that have influenced the architect over the years came together in this project: the attention to materials – five different types of stone are used from quarries located throughout Italy –, the reinterpretation of the traditional elements of Venetian city (recognizable in the narrow access path to the house, which Scarpa himself compares to a "Venetian calle") and the influence of contemporary masters such as Frank Lloyd Wright, clearly visible in the contrast between curved and straight lines in the plan of the building.

It is possible to identify the last twenty years of Scarpa’s career (1958-1978) as those in which the most complex and expressive projects were concentrated. This is due not only to his personal research on space and details, but also to an increase in his fame: in 1956 he won the Olivetti National Prize for architecture – and in the same year the company commissioned him a showroom in Piazza San Marco in Venice – and from this moment he begins to work for a client that grants him more resources and above all more freedom in design choices. This is particularly evident in his more mature projects mentioned above, such as the Castelvecchio Museum and Villa Ottolenghi, in which Scarpa's design philosophy is fully expressed: in both projects the variety of materials used – stone, concrete, copper, steel – and the complexity of the architectural joints clearly show that, according to him, the design of the detail is the generating element of the spatial quality of the entire project. The evolution of Scarpa’s architectural design principles reaches its peak with one of his best-known projects: the Brion Tomb.

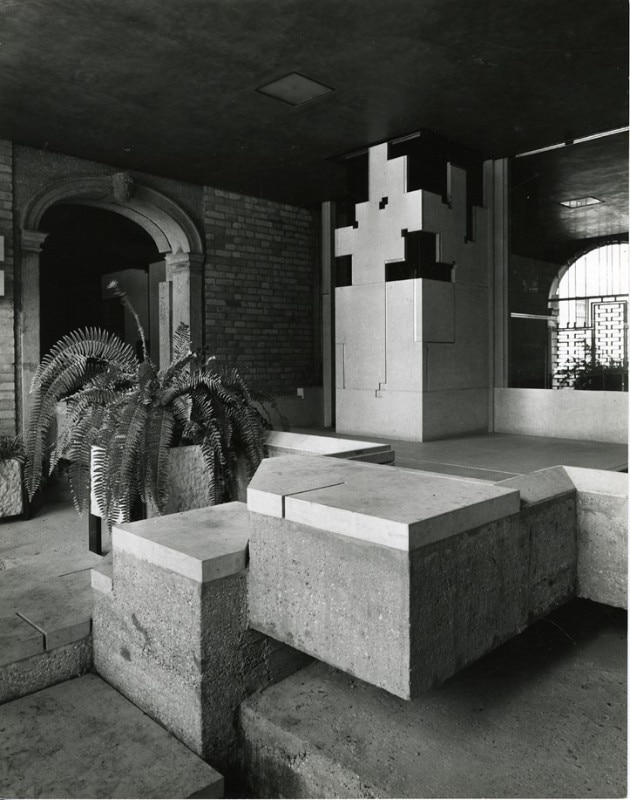

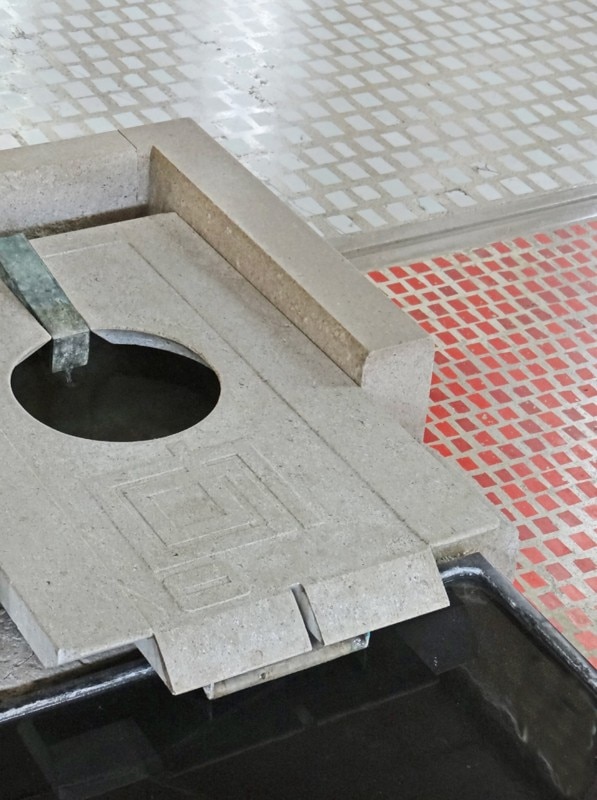

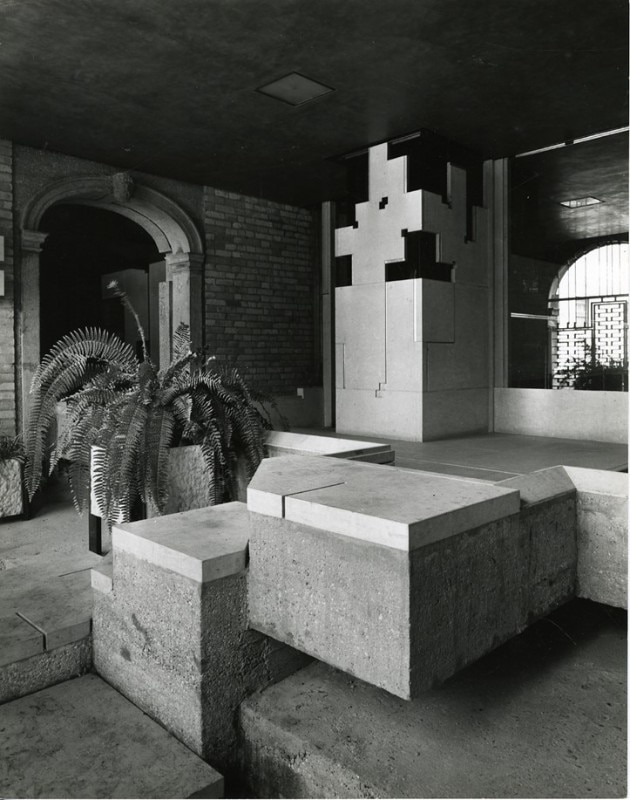

This project, commissioned in 1969 by Onorina Tomasin-Brion (wife of the founder of Brionvega Giuseppe Brion) to honor the memory of her husband, consists of an extension of the cemetery of San Vito in Altivole in the province of Treviso. The green areas, the chapel and the space with the sarcophagi of the couple are in dialogue with each other thanks to the presence of common architectural details but, at the same time, each spatial element is independent and gives a different contribution to the funerary complex. The simplicity of the materials used (exposed concrete, iron, wood) is balanced by the complexity of the architectural details which, however, do not make the project unnecessarily monumental. The dialogue between the built forms and nature – be it vegetation or water – holds together all the spaces of the complex.

From 1969 on, Scarpa travelled to Japan several times; his interest in the culture of this country goes beyond architecture: according to the designer's vision, Japanese society - which has preserved traditions and ceremonies unchanged for centuries - was a model of elegance and rigor that is reflected in the spatial principles they have developed over time. Japanese architecture, which Scarpa has studied since the years of his early studies, assigns a fundamental role to the relationship between architectural detail and the overall space (especially referring to the design of the structural nodes of wooden buildings) and, mostly in traditional buildings, often gives a central role to the relationship between man and nature

The year in which construction of the Brion Tomb ended, i.e. 1978, has also been the year of Scarpa's death, which occurred while he was in Japan to study the local culture. The architect was buried in an area of the Brion Tomb, by his explicit request. The cultural legacy left by Scarpa, who still influences many generations of architects today, consists mainly of his great ability to hold together different languages and tools, synthesizing them in an original and recognizable production: the influence of work with artisans, the value of drawing as instrument not only of representation but also of active thought, the suggestions related to Japanese culture and the influence of past and contemporary architects. These elements constitute the basis of Scarpa's design philosophy, according to which the spatial quality is a value that should not be researched through majesty and solemnity - as in well-known projects by Louis Kahn, an architect that Scarpa had the chance to meet and discuss with - but through the attention to architectural details and the dialogue of different elements: history and contemporaneity, natural elements and anthropic elements, specific languages (of a place, of a tradition, of an era) and universal languages.

from the words of Seiichi Shirai (1977):

Carlo Scarpa is unquestionably one of those few architects who, far from any conceptualizing, nurtures an almost instinctive inclination to delve deeper into the semantic depths of Space.

- Opening image :

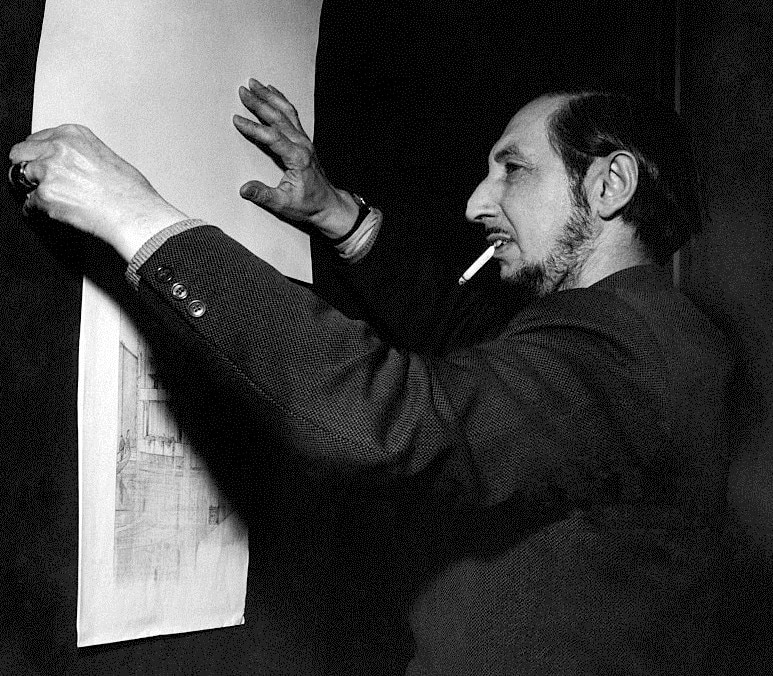

- Carlo Scarpa portrait by Mario De Biasi