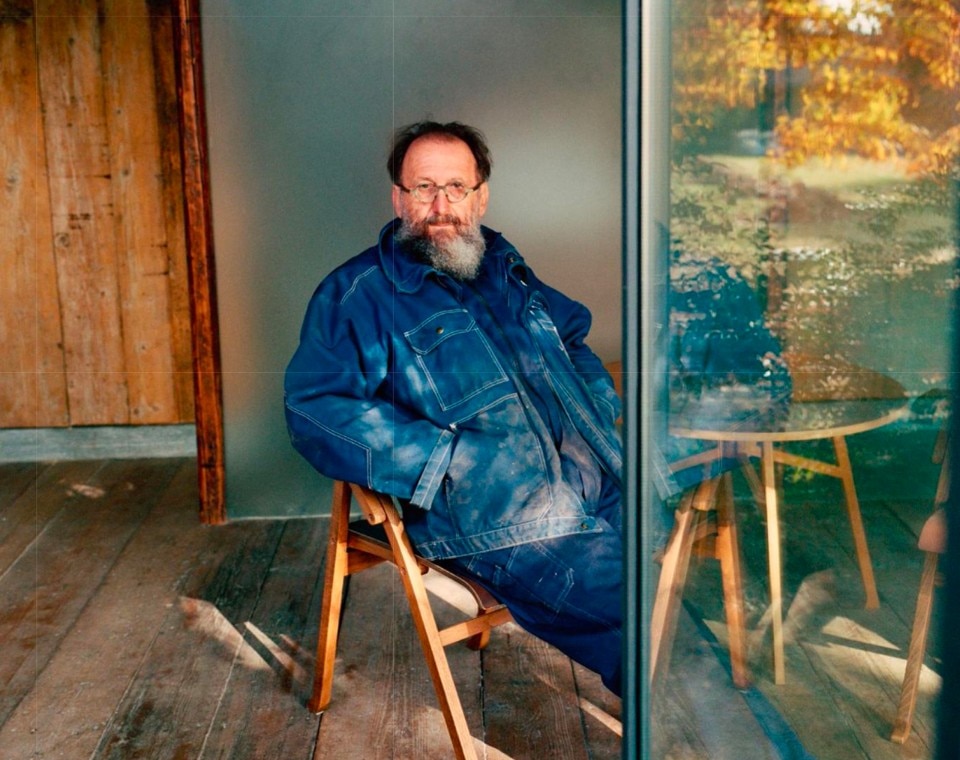

Michele De Lucchi (Ferrara, 1951) has kept a leading role in the Italian architectural and design scene for the past five decades, achieving great fame also beyond national borders starting from the mid-1980s. De Lucchi is an evolving figure, whose career can be subdivided into a few clear periods, corresponding to his approaching different design scales and disciplines.

During and after his master degree in Architecture, which he obtains in Florence in 1975, he gets in touch with the protagonists of the Italian radical movement: the Florentine group (Lapo Binazzi, Adolfo Natalini, Gianni Pettena), as well as their Milanese counterpart (Andrea Branzi, Alessandro Mendini), at a time when exchanges between the two were particularly thriving and productive.

De Lucchi is involved, for instance, in the Global Tools radical school and in Alessandro Guerriero’s Studio Alchimia, and he co-founds his own group Cavart, that curates a few memorable performances and installations within the caves of Colli Euganei. During this first part of the 1970s, De Lucchi and the other radicals are mostly the advocates of a rebel cultural project, which is interested in challenging and discussing the ways of production, more than in designing objects and buildings.

In 1976 De Lucchi moves to Milan, accepting Andrea Branzi’s invitation to contribute in the set-up of Il design italiano degli anni ’50 (“Italian design in the 1950s”), a seminal exhibition held at Centro Kappa. This is a crucial occasion, a breakthrough for De Lucchi in many regards: on a cultural plan, as he becomes familiar with the field of actual product design, but also, more broadly and more prosaically, on a professional and social plan. He gets to know here the main producers and designers working in Milan at the time, including the Castelli, Kartell’s founders, the Castiglioni brothers, as well as Vico Magistretti, Gio Ponti and Marco Zanuso.

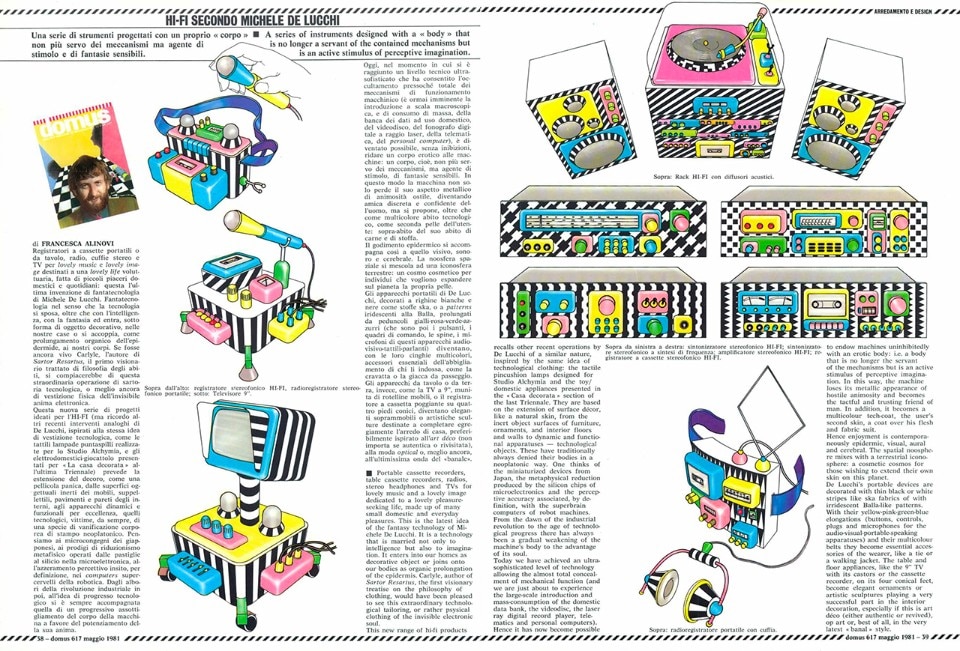

The encounter with Ettore Sottsass, though, proves to be by far the most significant in the long term. He calls De Lucchi to work in his office in 1978, he introduces him to Olivetti, that De Lucchi will collaborate with as a a consultant from 1979 to 2002, and he involves him in the Memphis movement, starting from the early 1980s. De Lucchi acknowledges on several occasions the influence of his master, to the extent that he can comfortably state: “I did copy him for years; I was eating like Sottsass, dressing up like Sottsass…”.

View gallery

View gallery

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

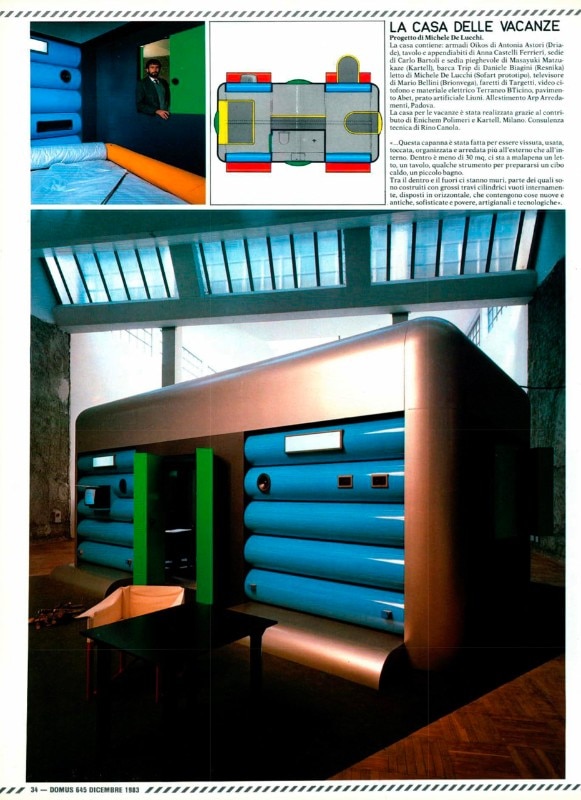

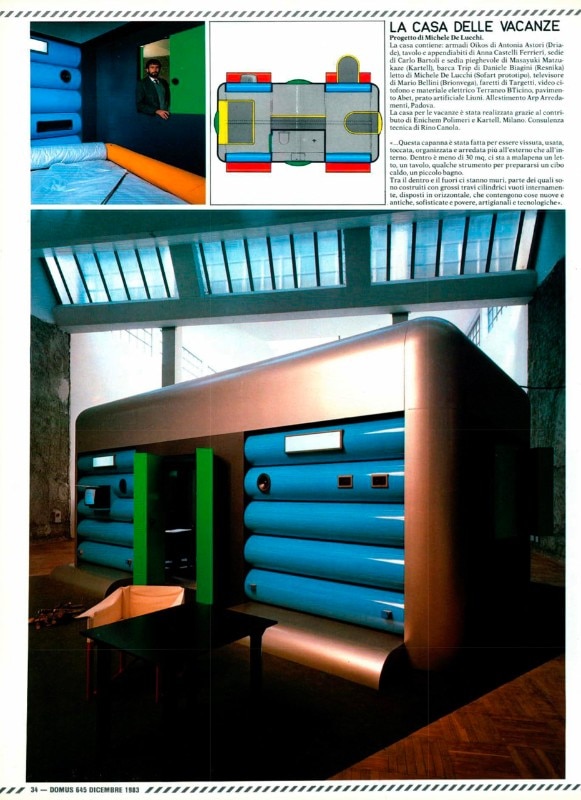

Michele De Lucchi, Holiday house, 1983. Photo © Miro Zagnoli. From Domus 645, December 1983

Michele De Lucchi, New Deutsche Bank branches, 1990. Photo © Matteo Piazza. From Domus 735, February 1992

Michele De Lucchi, New Deutsche Bank branches, 1990. Photo © Matteo Piazza. From Domus 735, February 1992

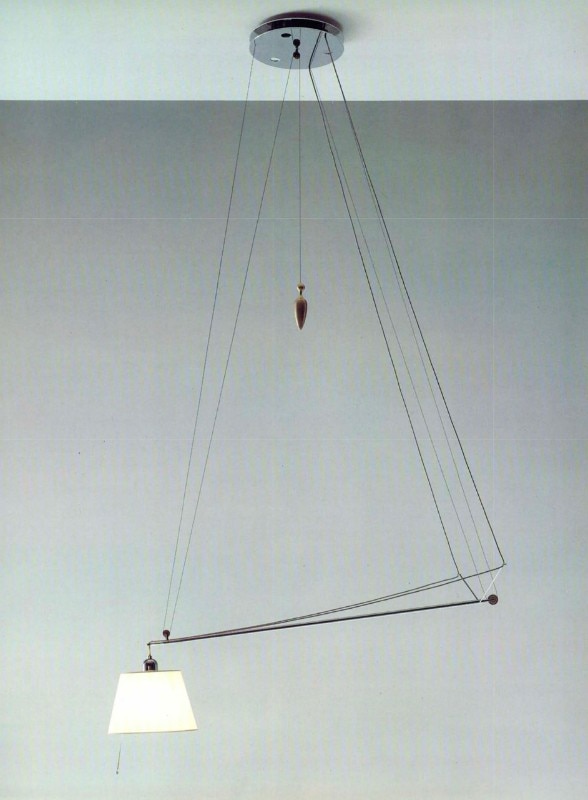

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Macchina Minima” n. 7 lamp, 1992. Photo © Francesco Radino. From Domus 744, December 1992

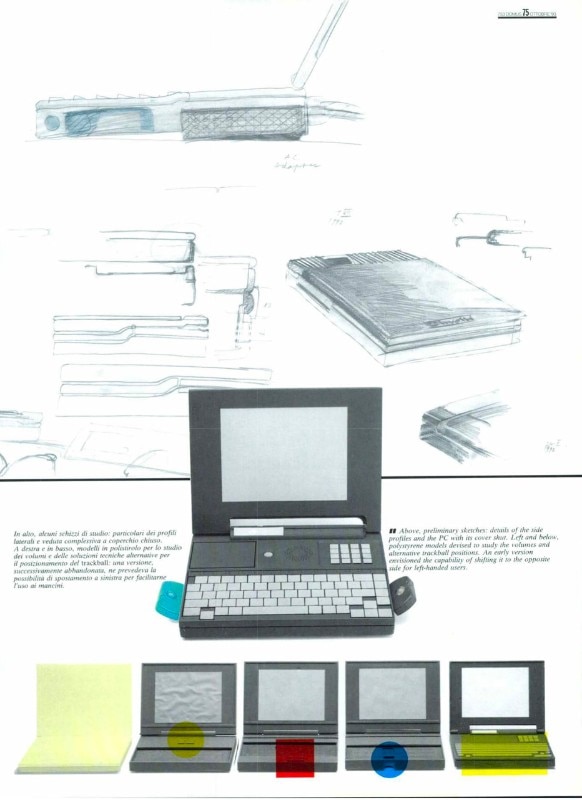

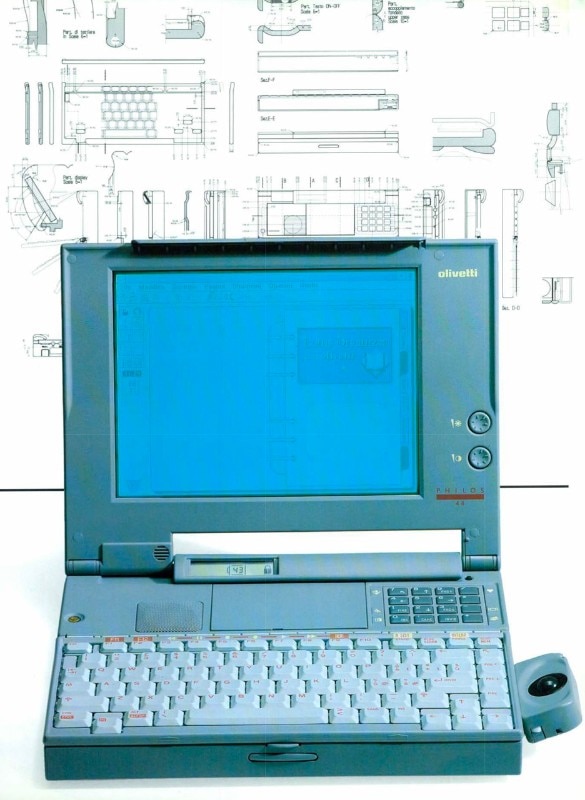

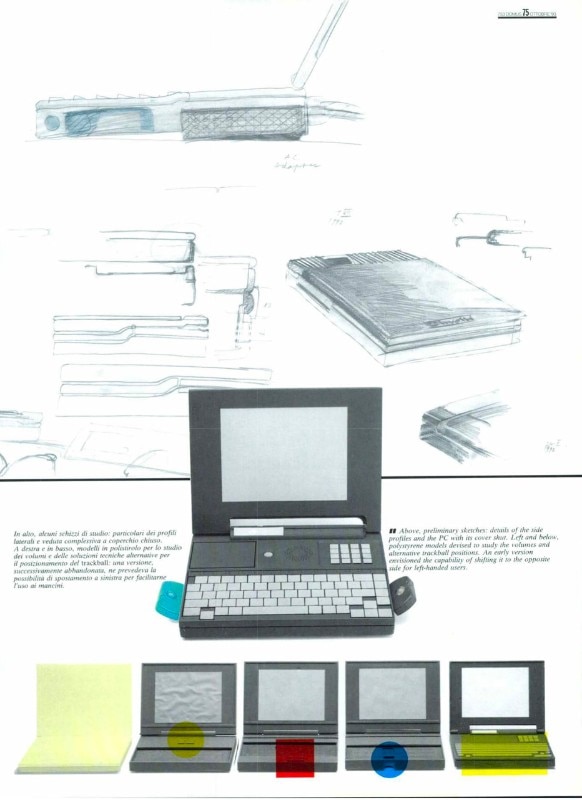

Michele De Lucchi, Hagai Shvadron, Personal Computer Philos, 1993. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 753, October 1993

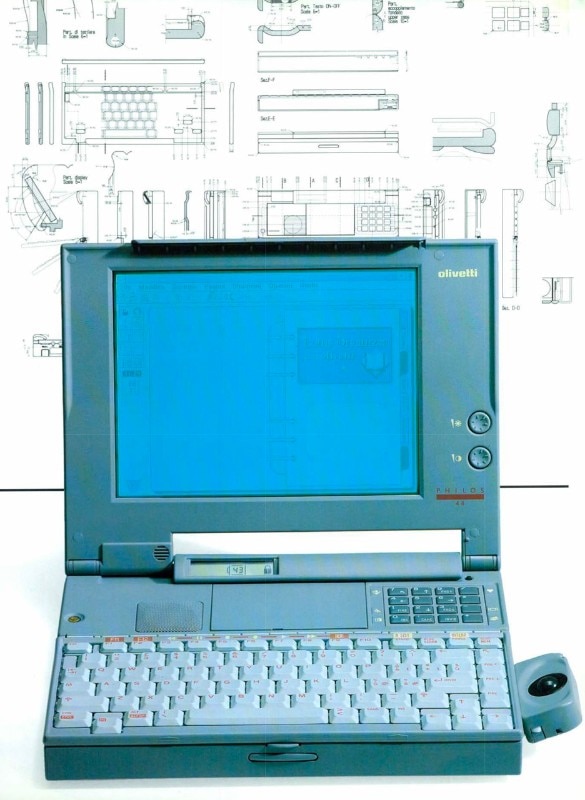

Michele De Lucchi, Hagai Shvadron, Personal Computer Philos, 1993. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 753, October 1993

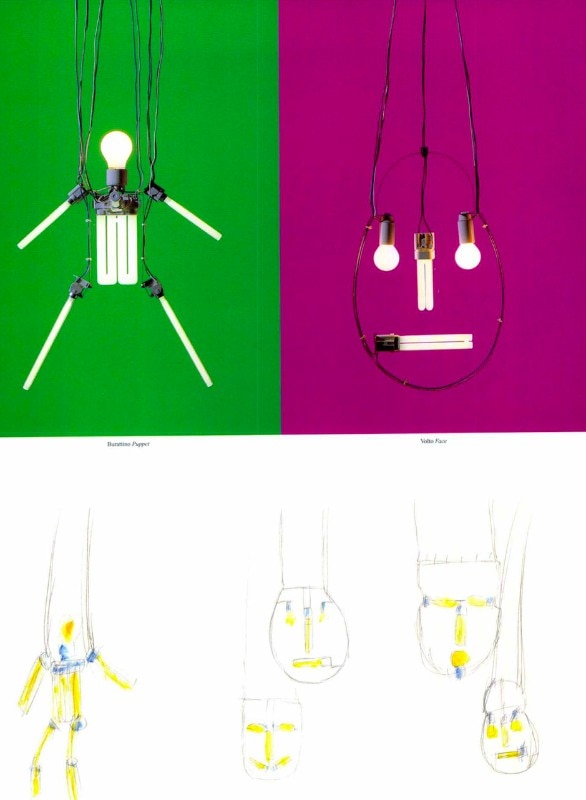

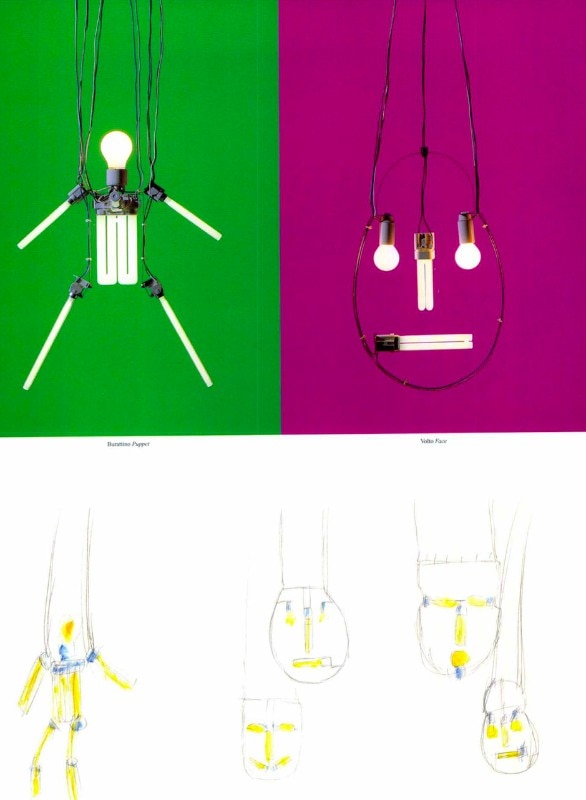

Michele De Lucchi, Mario Rossi Scola, Minimal Lamps, 1997. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 790, February 1997

Michele De Lucchi, Mario Rossi Scola, Minimal Lamps, 1997. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 790, February 1997

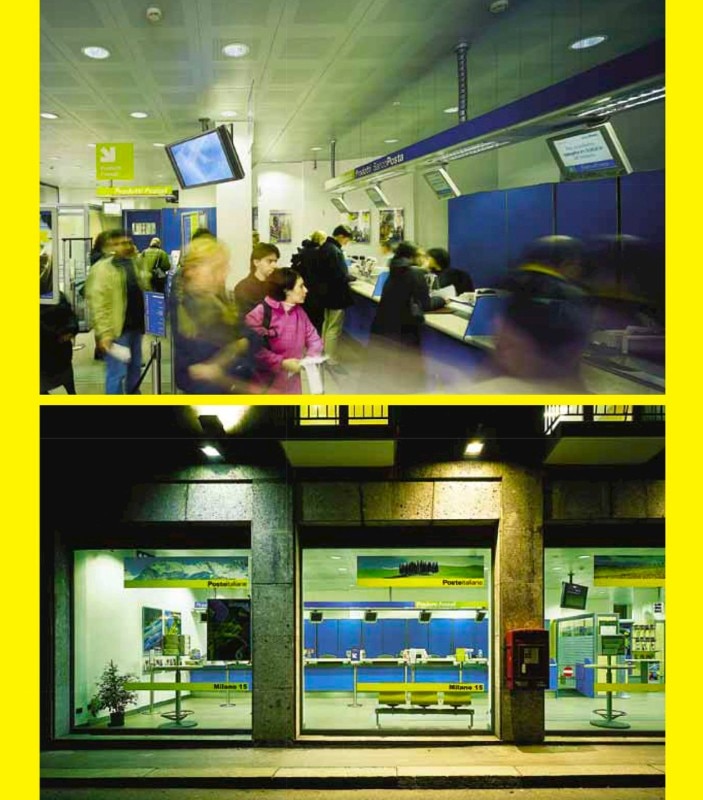

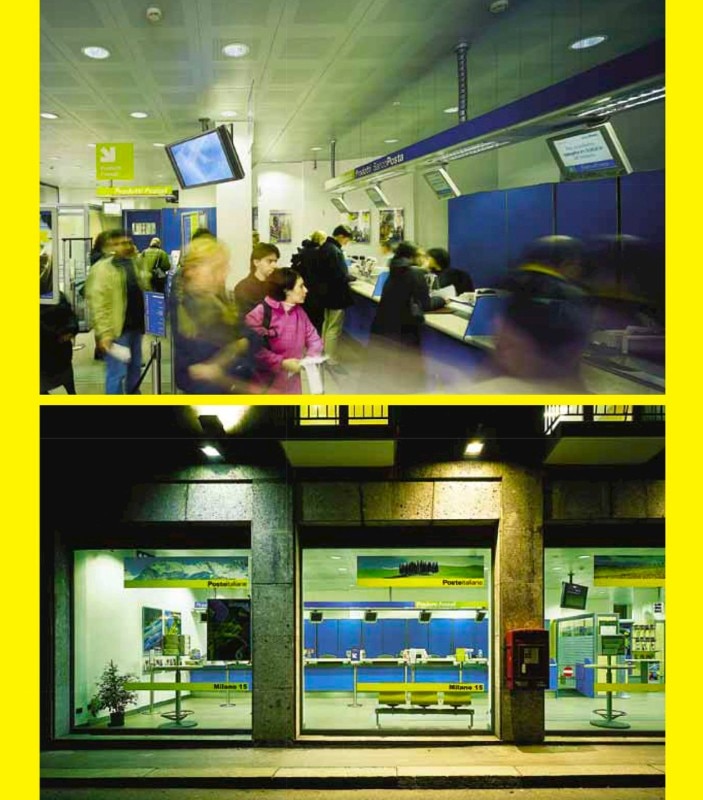

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

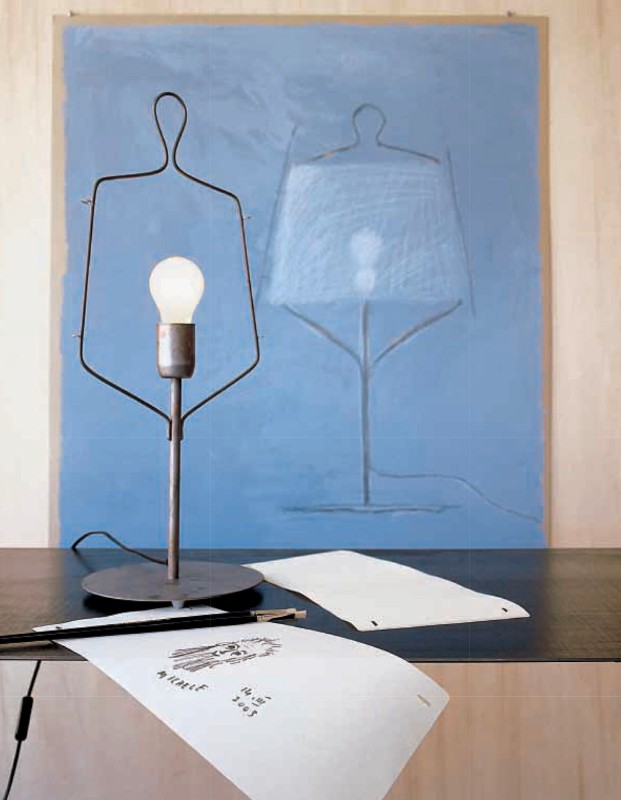

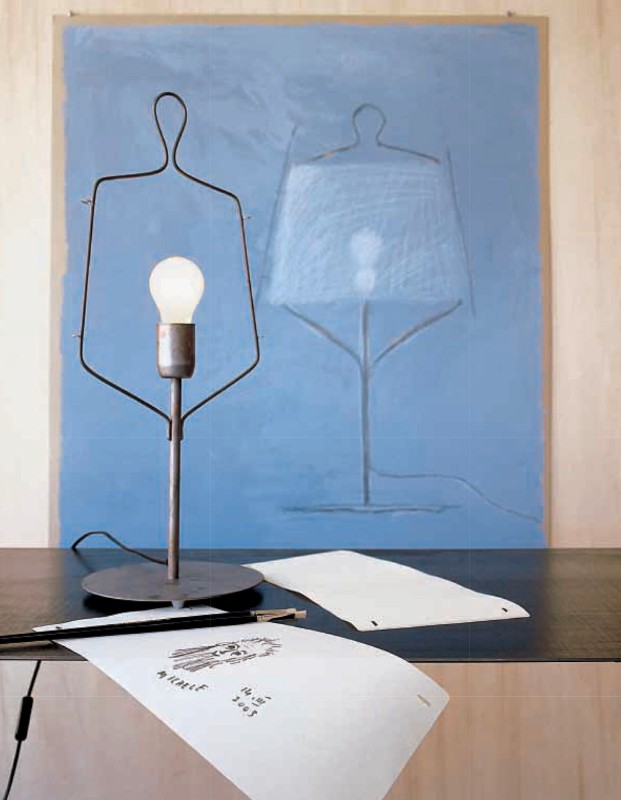

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Acquamiki” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Acquatinta” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Artista” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

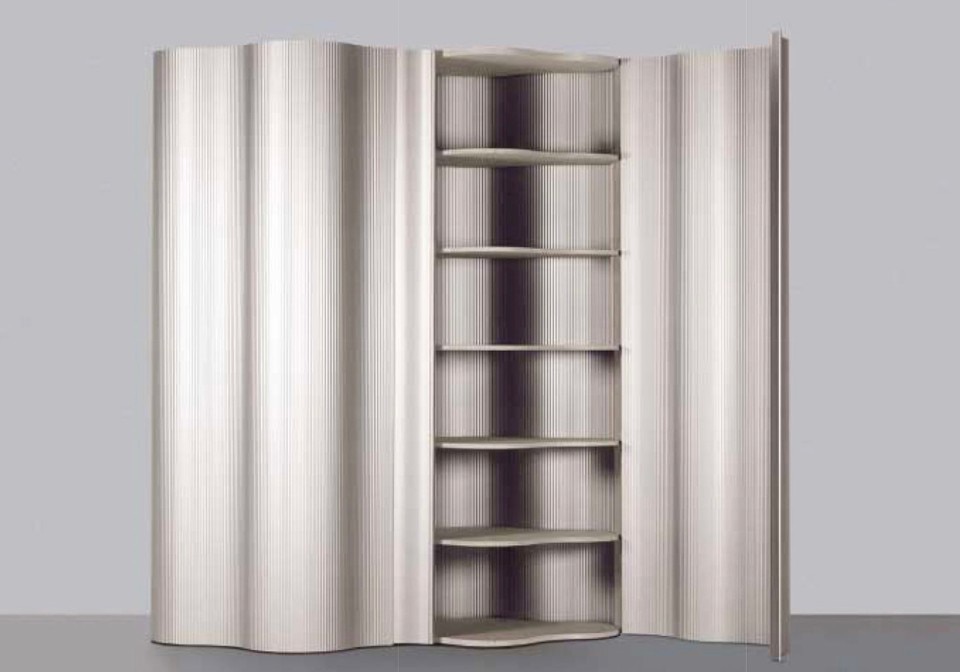

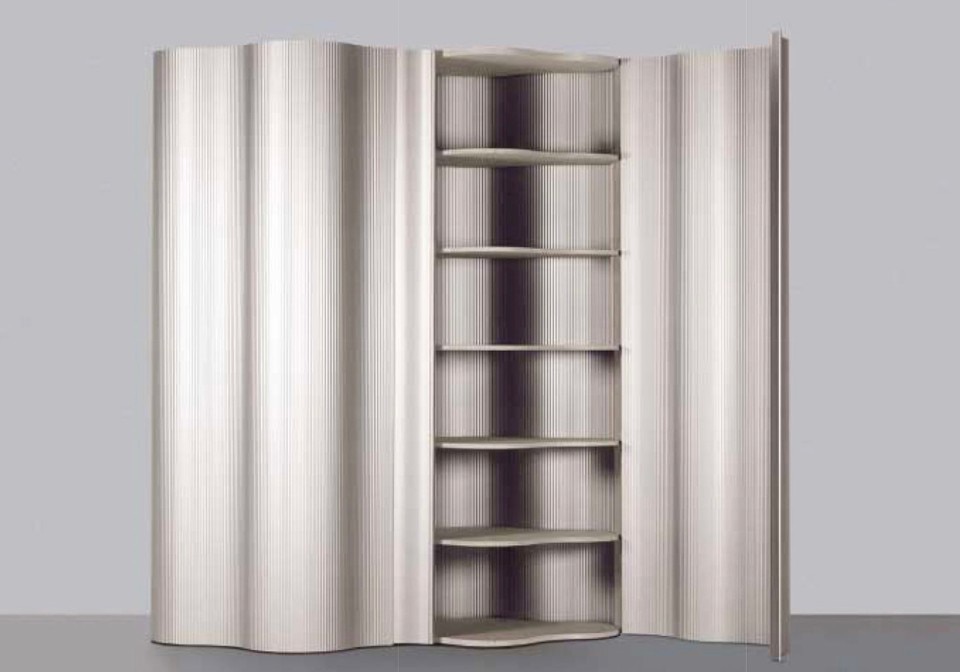

Michele De Lucchi, “Layout” cabinet for Alias, 2004. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 871, June 2004

Michele De Lucchi, “Layout” cabinet for Alias, 2004. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 871, June 2004

Michele De Lucchi, T3 Tower, 2007. Photo © Michele De Lucchi. From Domus 940, October 2010

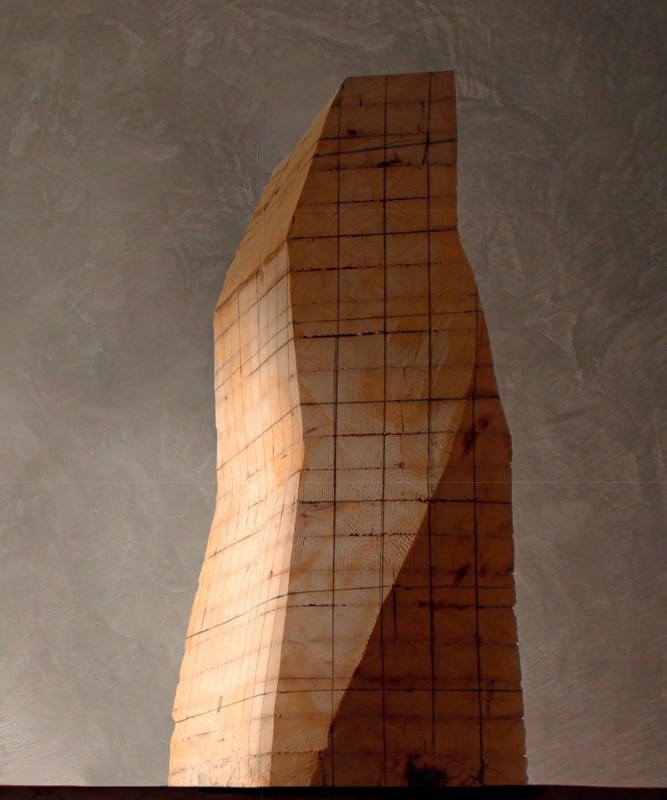

Michele De Lucchi, T1 Tower, 2007. Photo © Michele De Lucchi. From Domus 940, October 2010

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

aMDL, Unicredit Pavilion, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Tom Vack. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Padiglione Zero, Expo Milano 2015, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Alessandra Chemollo. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Padiglione Zero, Expo Milano 2015, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Tom Vack. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Bridge of Peace, Tblisi, Georgia, 2010. Photo © Gia Chkatarashvili. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

Michele De Lucchi, Holiday house, 1983. Photo © Miro Zagnoli. From Domus 645, December 1983

Michele De Lucchi, New Deutsche Bank branches, 1990. Photo © Matteo Piazza. From Domus 735, February 1992

Michele De Lucchi, New Deutsche Bank branches, 1990. Photo © Matteo Piazza. From Domus 735, February 1992

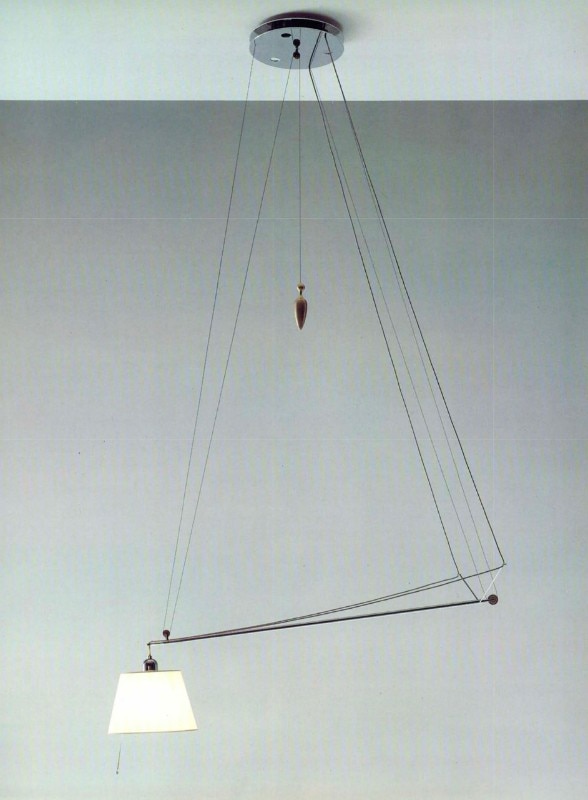

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Macchina Minima” n. 7 lamp, 1992. Photo © Francesco Radino. From Domus 744, December 1992

Michele De Lucchi, Hagai Shvadron, Personal Computer Philos, 1993. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 753, October 1993

Michele De Lucchi, Hagai Shvadron, Personal Computer Philos, 1993. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 753, October 1993

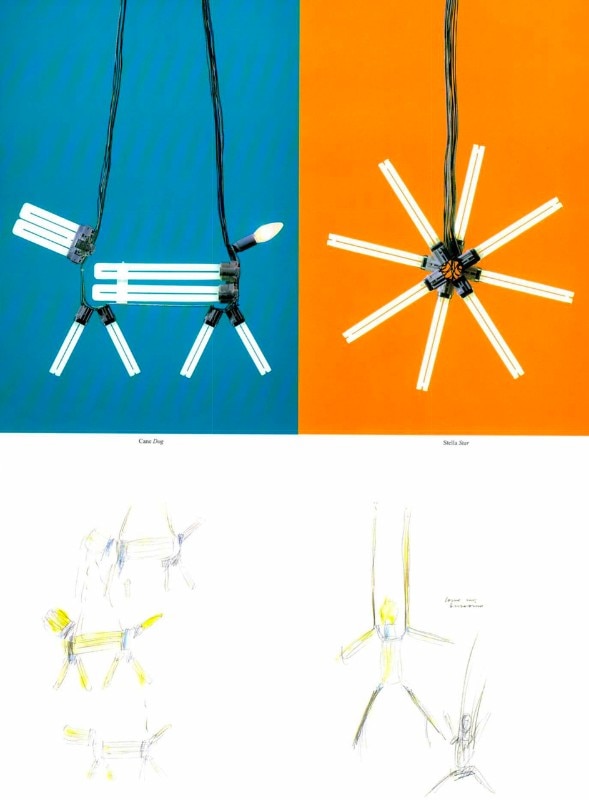

Michele De Lucchi, Mario Rossi Scola, Minimal Lamps, 1997. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 790, February 1997

Michele De Lucchi, Mario Rossi Scola, Minimal Lamps, 1997. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 790, February 1997

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

Michele De Lucchi, Poste Italiane, 2001. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 834, February 2001

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Acquamiki” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Acquatinta” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

Michele De Lucchi, Produzione Privata, “Artista” lamp. Photo © Christoph Kicherer. From Domus 859, May 2003

Michele De Lucchi, “Layout” cabinet for Alias, 2004. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 871, June 2004

Michele De Lucchi, “Layout” cabinet for Alias, 2004. Photo © Donato Di Bello. From Domus 871, June 2004

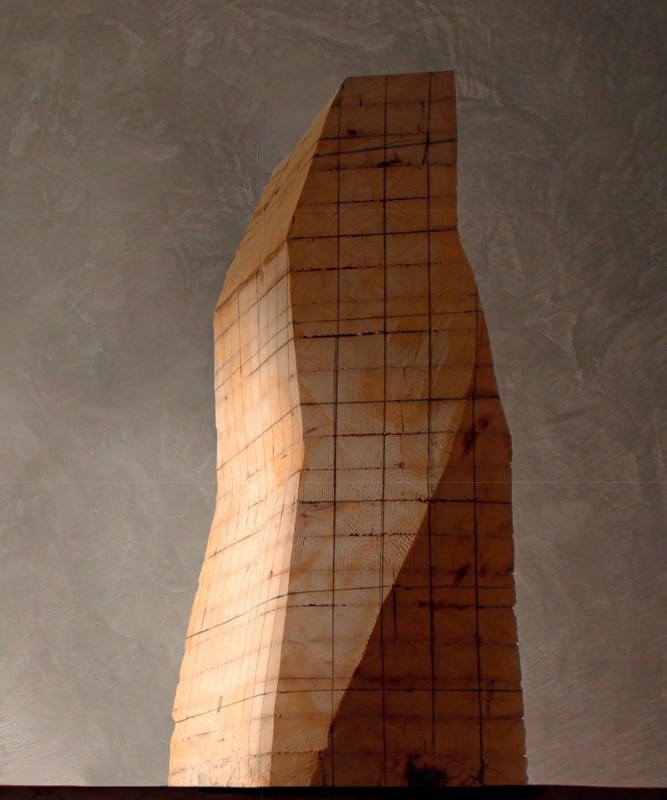

Michele De Lucchi, T3 Tower, 2007. Photo © Michele De Lucchi. From Domus 940, October 2010

Michele De Lucchi, T1 Tower, 2007. Photo © Michele De Lucchi. From Domus 940, October 2010

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

Michele De Lucchi, Office building, Pforzheim, Germany, 2014. Photo © Christian Richters. From Domus 983, September 2014

aMDL, Unicredit Pavilion, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Tom Vack. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Saint James Chapel, Bavaria, 2012. Photo © Thomas Koller. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Padiglione Zero, Expo Milano 2015, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Alessandra Chemollo. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Padiglione Zero, Expo Milano 2015, Milan, Italy, 2015. Photo © Tom Vack. From Domus 1019, December 2017

aMDL, Bridge of Peace, Tblisi, Georgia, 2010. Photo © Gia Chkatarashvili. From Domus 1019, December 2017

Also thanks to the latter, a few years after his arrival in Milan, De Lucchi has already activated the two main fields of his activity over the following two decades: product design and corporate image. For the former, besides the objects designed for Memphis, and later for Produzione Privata, it is worth mentioning at least the “Tolomeo” lamp from 1987. It is possibly the most famous of De Lucchi’s projects, but also the best and most successful outcome of the long lasting collaboration with Ernesto Gismondi’s Artemide.

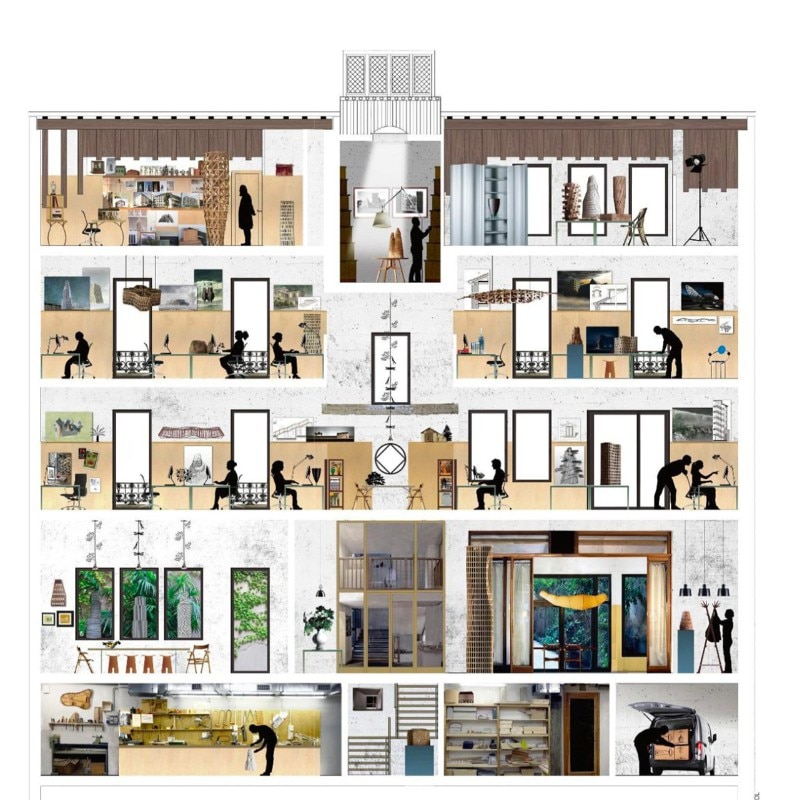

In the corporate field, the partnership with Olivetti is followed by several other companies and institutions: amongst the other, Banca Intesa, Deutsche Bank, Enel, Eni, Poste Italiane, Unicredit, listed here in alphabetical rather than chronological order. Besides the specificities of each case, De Lucchi always proves able to combine the need for efficiency to the quality of the spatial experience, and to mediate between the site-specific customization of each branch and the identifiability of the brand identity.

Over the 1990s and the years 2000 De Lucchi’s activity as an architect rapidly intensifies, in parallel with the progressive multiplication of international opportunities. In addition to several interior design projects, the most considerable results of this approach to the scale of the building are, at least in terms of volume, the office building “The Trunk”, in Pforzheim, Germany (2012), and above all the several realizations accomplished in Tbilisi. The Bridge of Peace (2010) in the Georgian capital is particularly representative of a sculptural approach to architecture, conceived in the first place as the result of the modeling of its volumes. And it is not by chance if De Lucchi continues at the same time his artistic research, centered around the many “towers” and “casette” (“little houses”), all carved in wood. These objects remain suspended between a purely evocative dimension and the prefiguration of built architectures.

The years 2010 are an exceptionally successful period for De Lucchi, the absolute star of Milan’s glorious decade. Besides the many temporary structures for Expo 2015 (such as the Pavilion Zero and the Intesa Sanpaolo Pavilion), he realizes a series of permanent set-ups and architectures of great urban relevance. These include the Unicredit Pavilion (2015), the renovation of the Franco Parenti Theatre (since 2008) and of the Gallerie d’Italia Museum (2012), and most importantly the redesing of the room hosting the Pietà Rondanini at the Castello Sforzesco (2015), where he dialogues with the memory of BBPR’s former design.

At the end of the decade he designs the set-up forThere is a planet, the large retrospective exhibition about Ettore Sottsass curated at the Triennale di Milano by Barbara Radice (September 2017-March 2018), and he is guest editor of Domus in 2018. These two commissions, amongst many others, confirm De Lucchi’s privileged link with his adoptive city, as well as his cultural prestige at a national and worldwide scale.

In the words of Ugo La Pietra:

Michele De Lucchi could be defined as the most representative heir of a design process that began in the 1950s and ‘60s in Italy. Popularly referred to as design that ranges “From the spoon to the city”, it designated a work method that can be applied to different disciplinary fields and different scales of projects