Since the pre-war years in America, specifically the United States, an autonomous discourse on architectural innovation developed, moving from the Europe-centered discourse of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) towards different propositions that could better embody the peculiarity of a geographic context.

Modern Architecture: International Exhibition (1932), the iconic exhibition curated by Henry Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson at the MoMA in New York — commonly considered as the date of birth of a modern “International Style” — already presented some remarkably American sections, in terms of participants and topics, mostly connected to issues of dwelling. Several manifold trajectories spring all from a same point: the fact that the starting conditions in America were way different from those characterizing Europe, the proper cradle of Modernism Movement. The US were not damaged on their own territory by World War II; still, all the efforts in economy and design research, were employed in war or emergency industry, and the same happened for the youngest resources on the scene. For these same reasons, a major advancement in technology provided a wider access to new materials and techniques (plastics, insulation panels, steel welding and so on).

An urge to bring all this progress back into the realm of civilian architecture would therefore mark the beginning of a proper era.

View gallery

View gallery

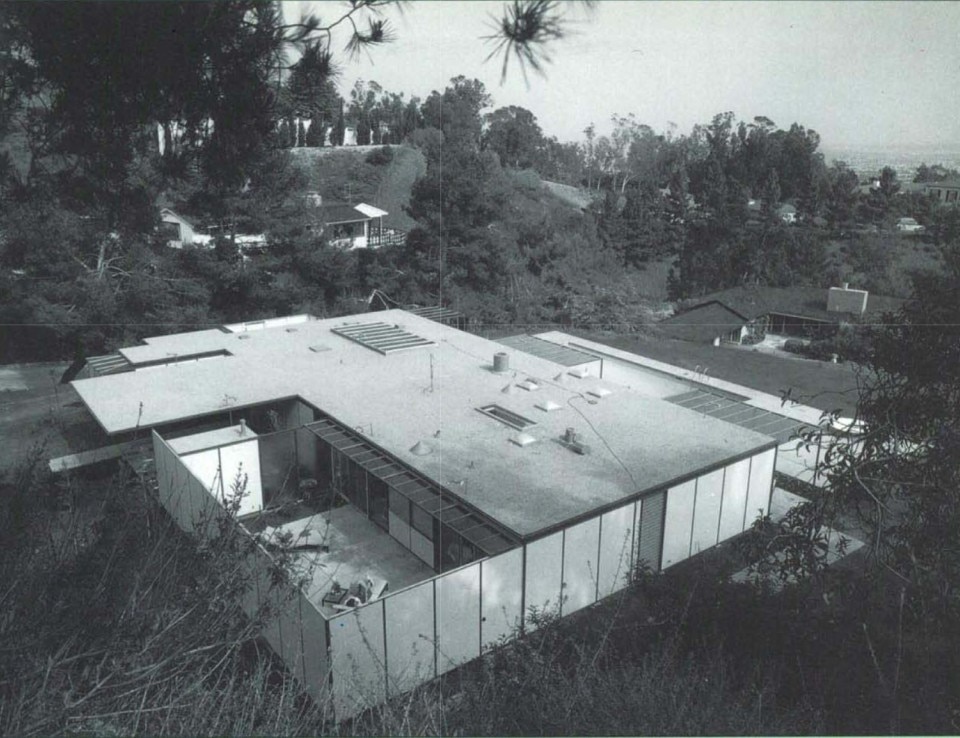

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Bird’s eye view. In Domus n.711, December 1989

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Plan. In Domus n.711, December 1989

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House, Los Angeles. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

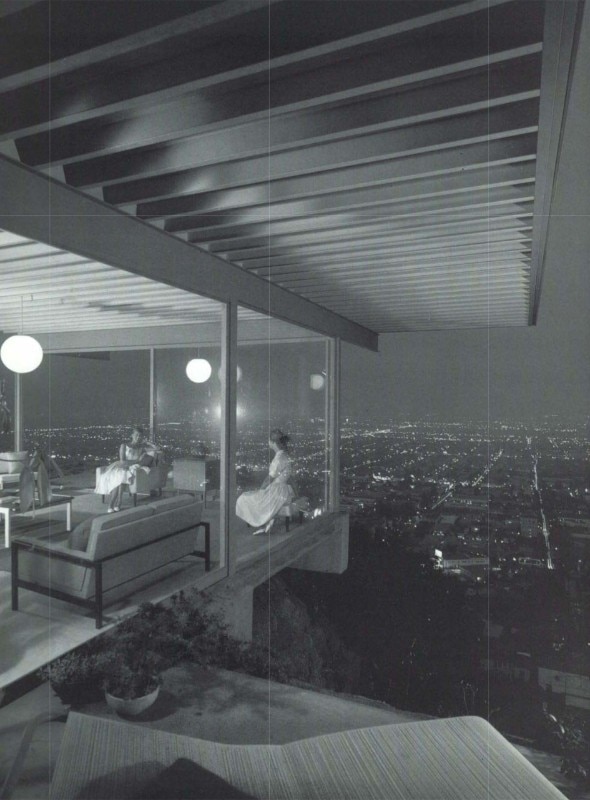

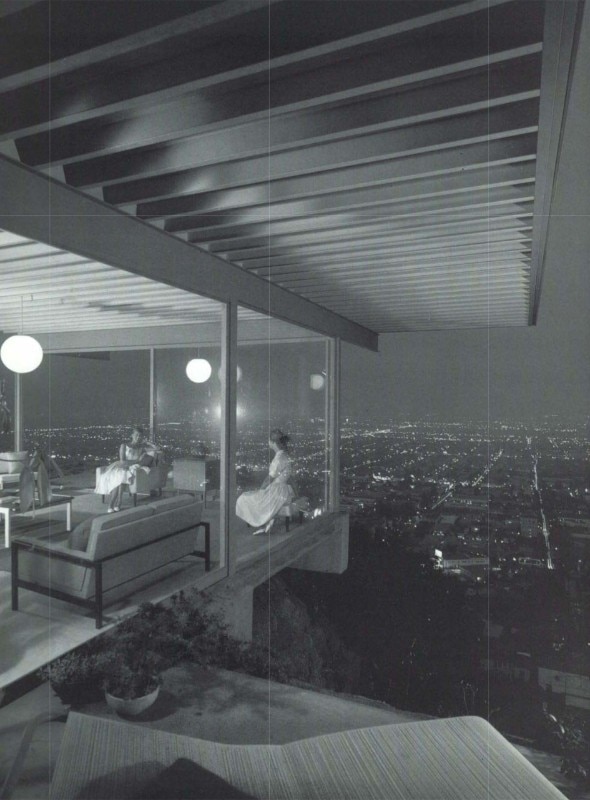

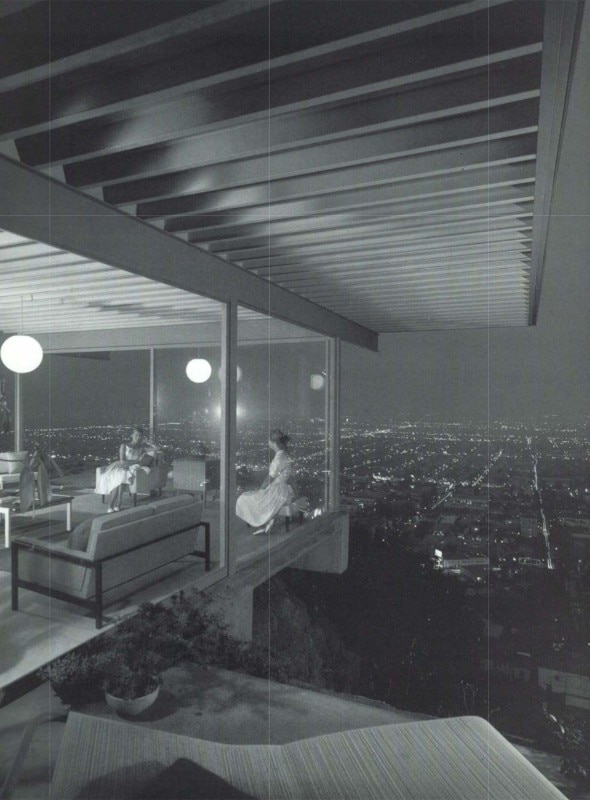

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. View on the cantilevered living room. In Domus n.711, December 1989

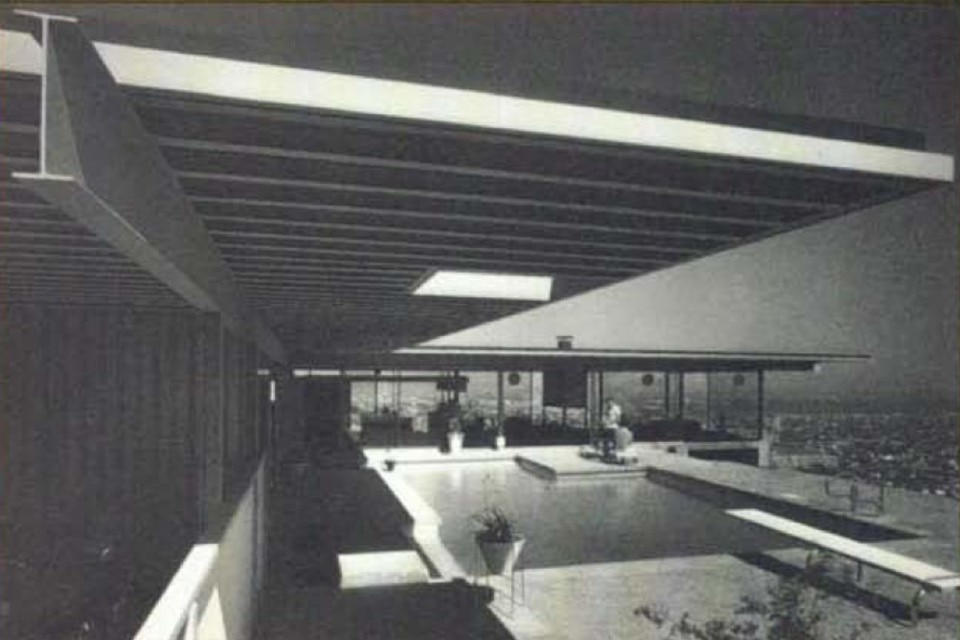

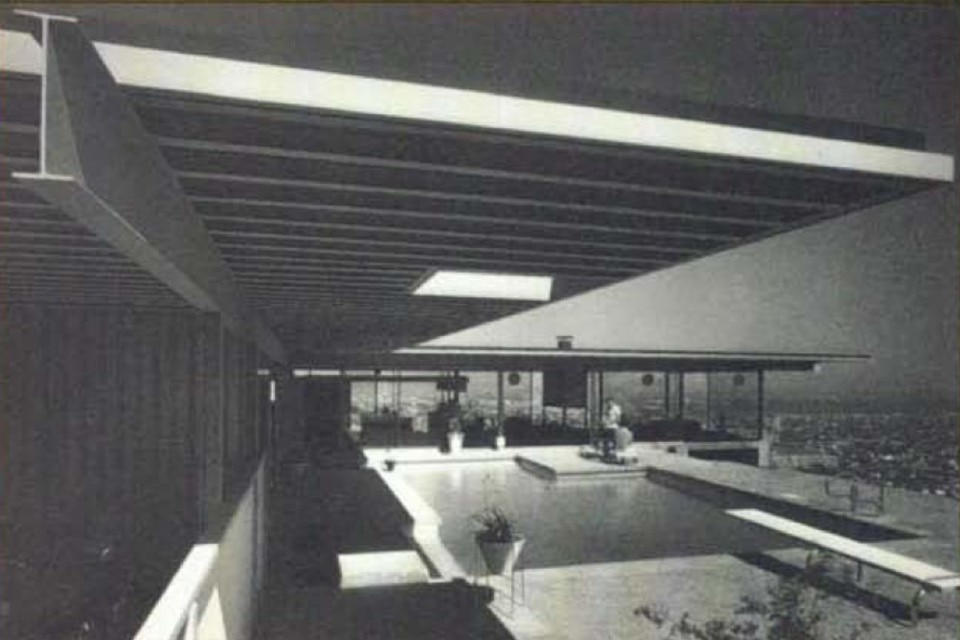

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. Exterior view. In Domus n.711, December 1989

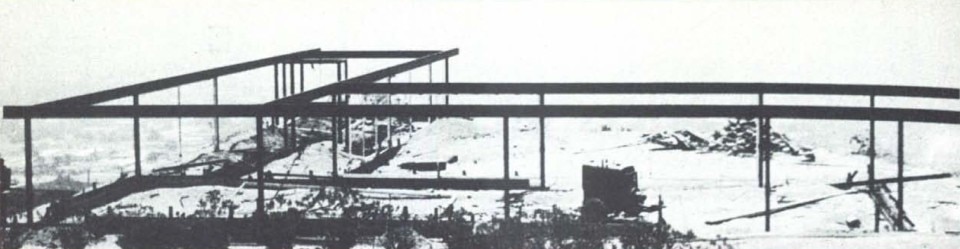

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. The steel structure under construction. In Domus n.711, December 1989

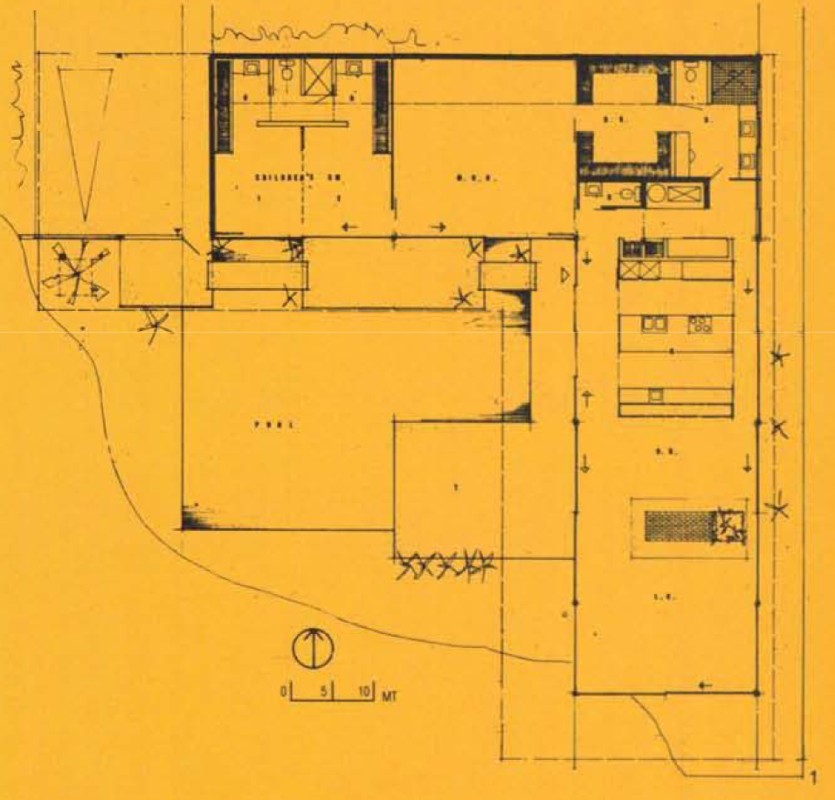

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. Plan. In Domus n.711, December 1989

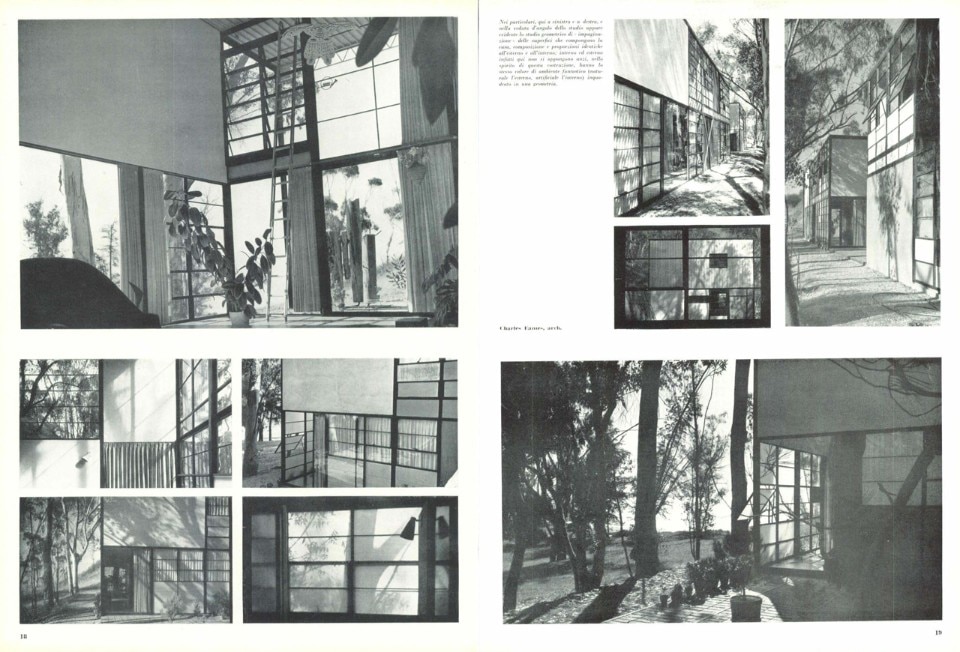

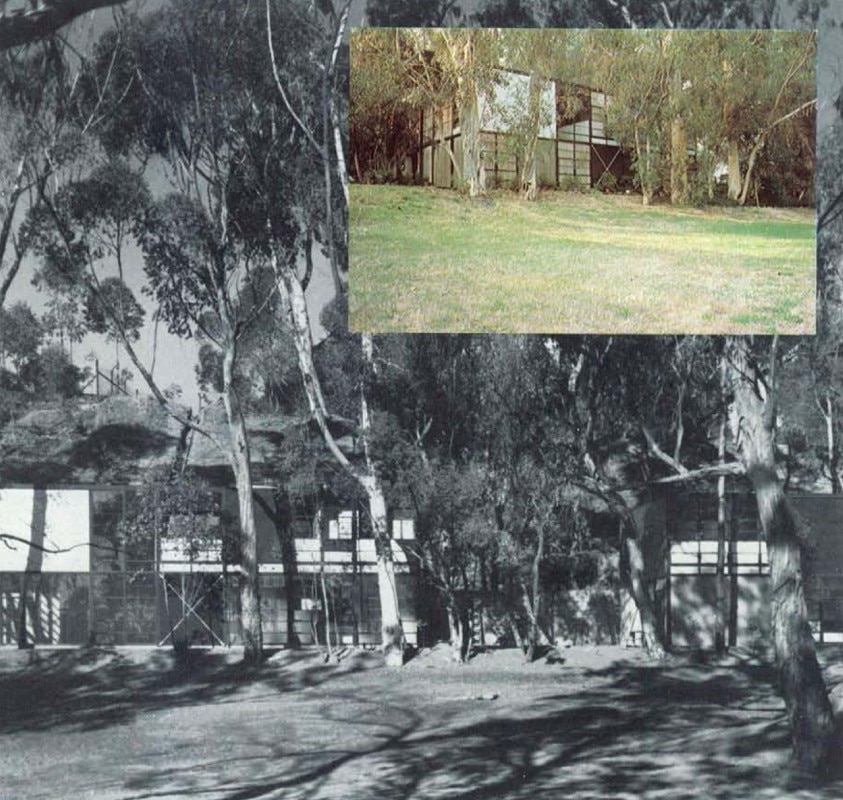

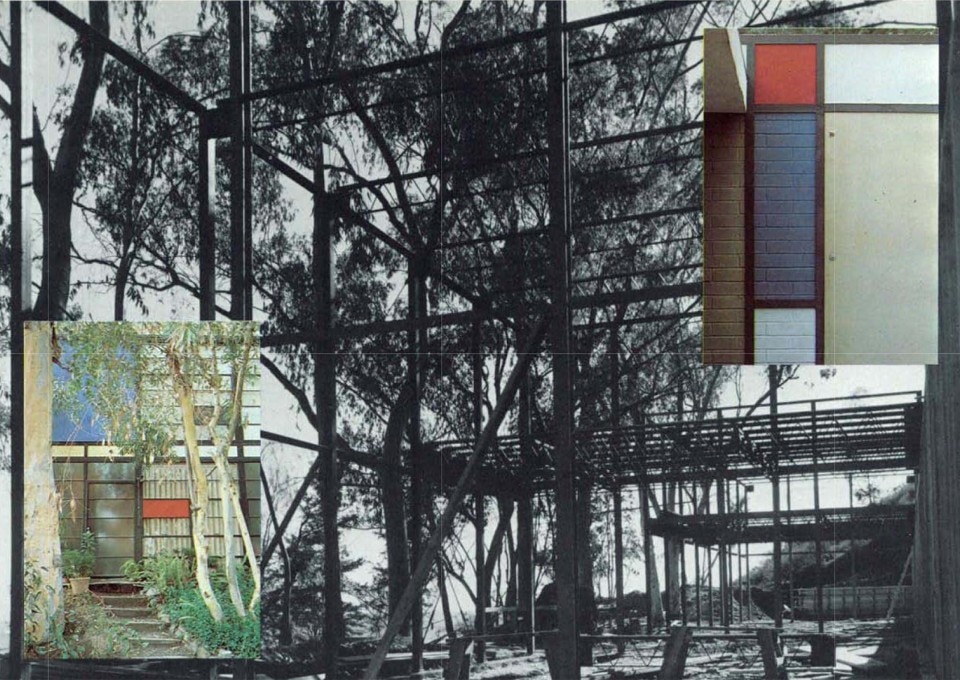

Charles and Ray Eames (with Eero Saarinen), Case Study House 8 (Eames House), 1945-49, Santa Monica, California. Exterior views. In Domus n. 614, February 1981

Charles and Ray Eames (with Eero Saarinen), Case Study House 8 (Eames House), 1945-49, Santa Monica, California. Exterior views. In Domus n. 614, February 1981

Killingswoth, Brady & Smith, Cambridge Investment inc. Building, Long Beach, 1960. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Lutah Maria Riggs, Peter Berkey III House, Carpinteria, 1961. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

William Pereira & Associates, Pereira Residence, Los Angeles, 1964. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Killingswoth, Brady & Smith, Killingswoth, Brady & Smith office, Long Beach, 1957. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Richard J. Neutra, Windshield, view from Northwest, September 1939. Photography by Harold H. Costain. Courtesy of Special Collections, Young Library, UCLA

Richard J. Neutra, Windshield, interior view, September 1939. Photography by Harold H. Costain. Courtesy of Special Collections, Young Library, UCLA

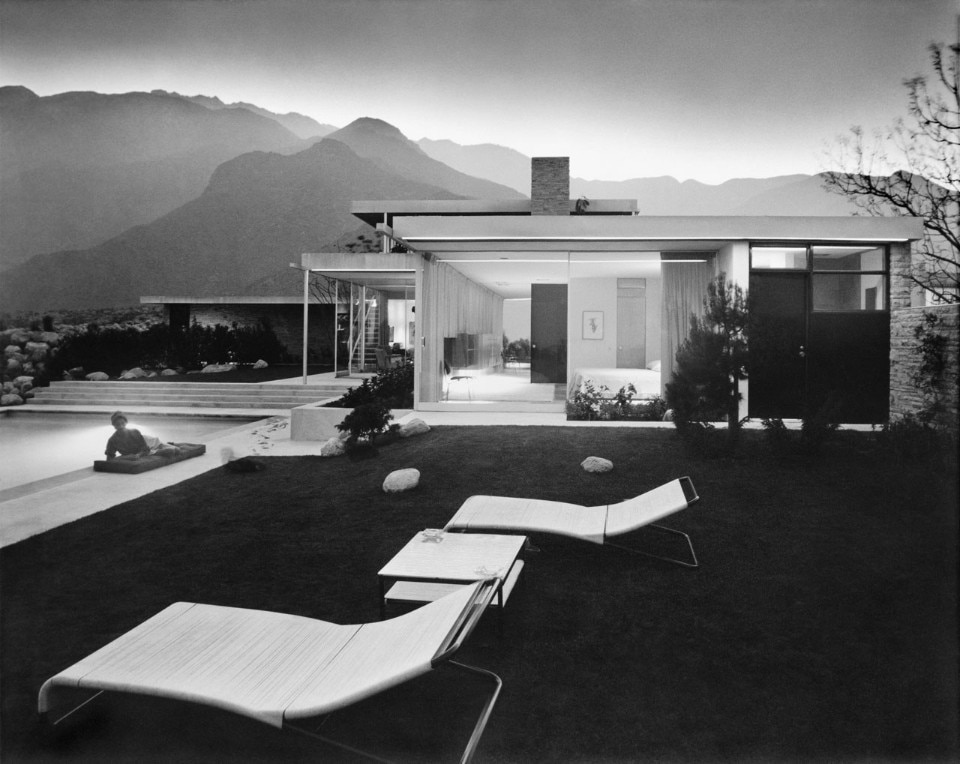

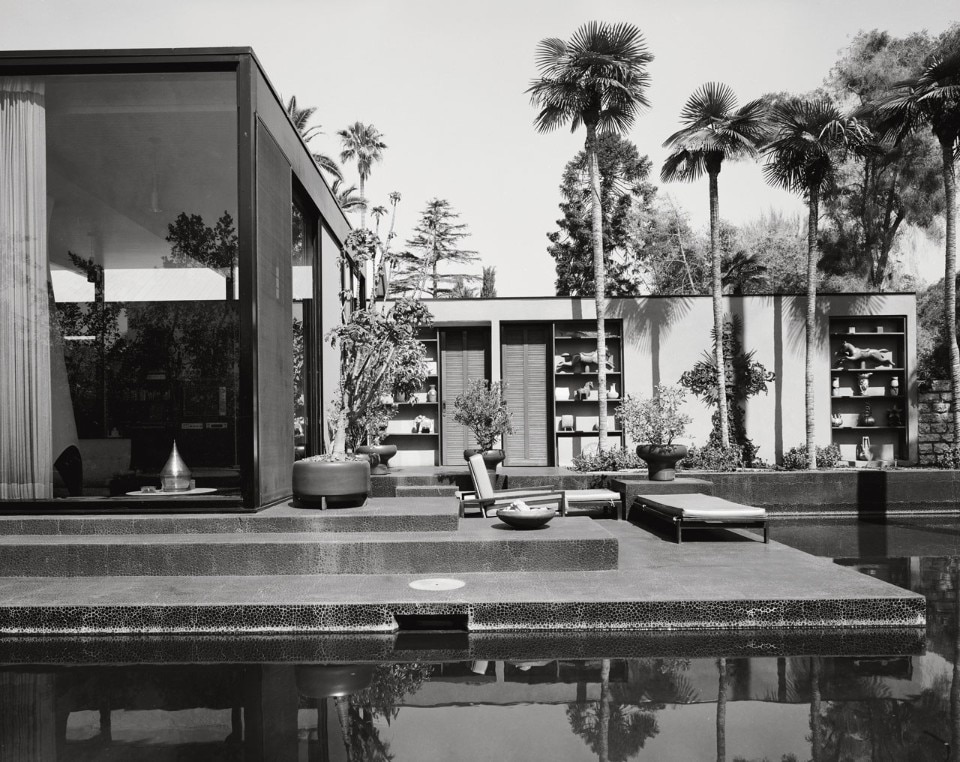

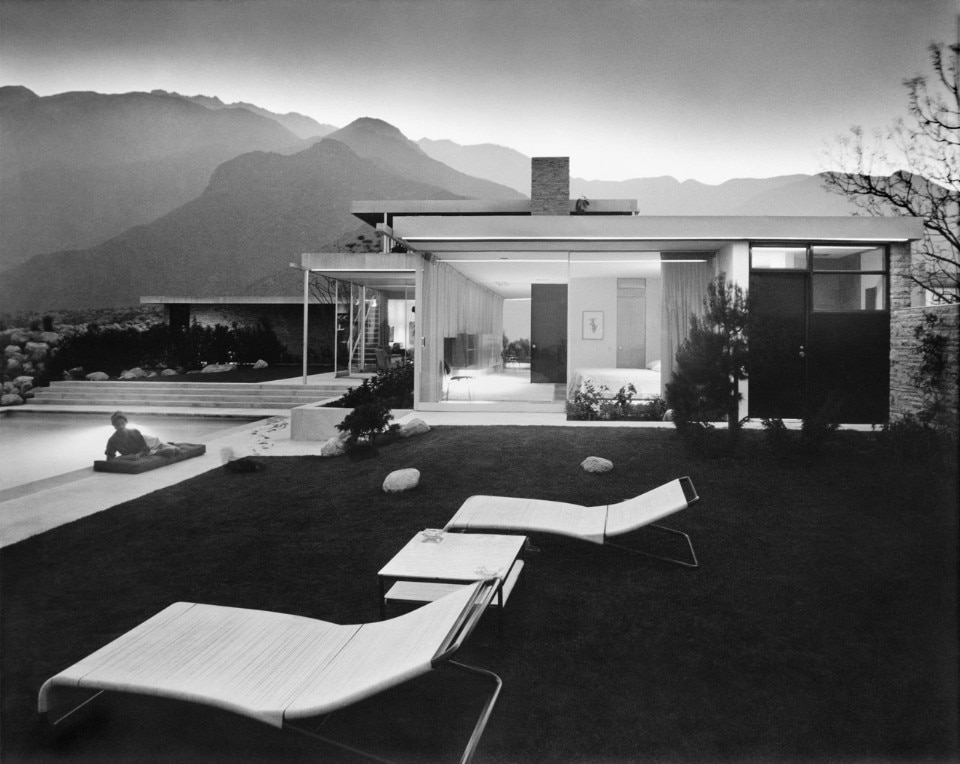

Julius Shulman, Kaufmann House designed by Richard Neutra (Palm Springs, CA), 1947. Gelatin silver print. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute. Copyright © J. Paul Getty Trust

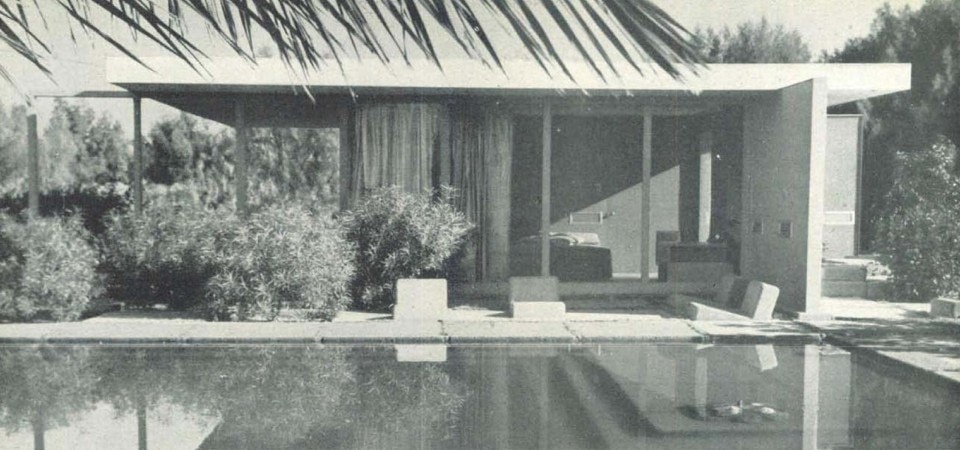

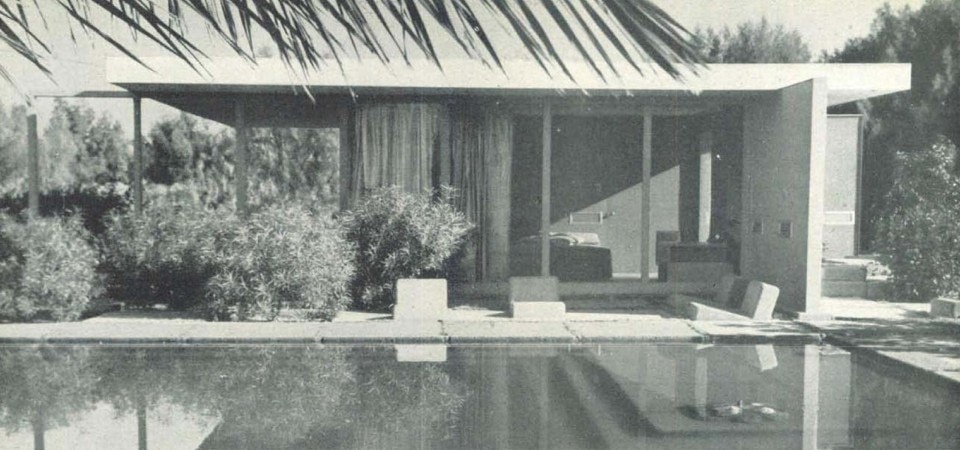

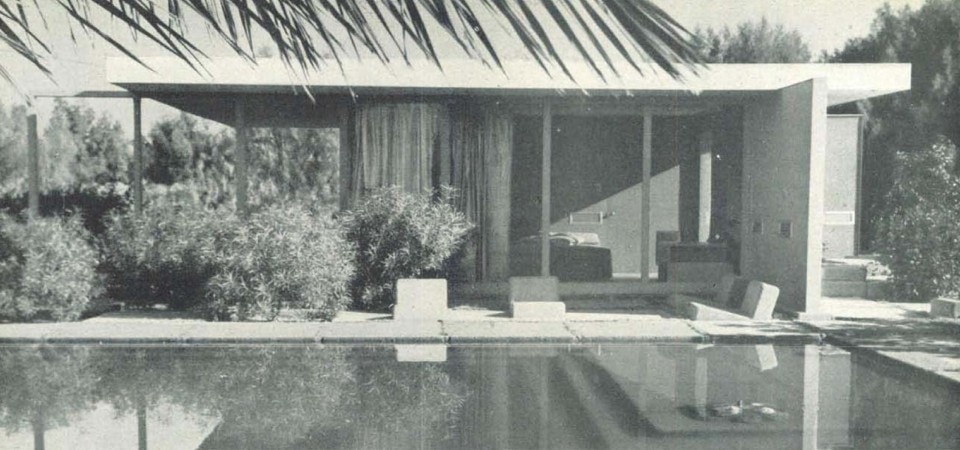

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Exterior view. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Exterior view from the swimming pool. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

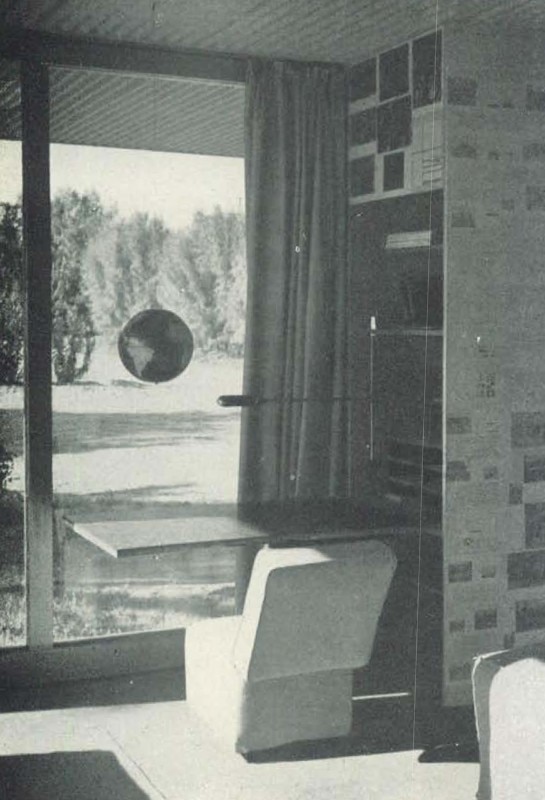

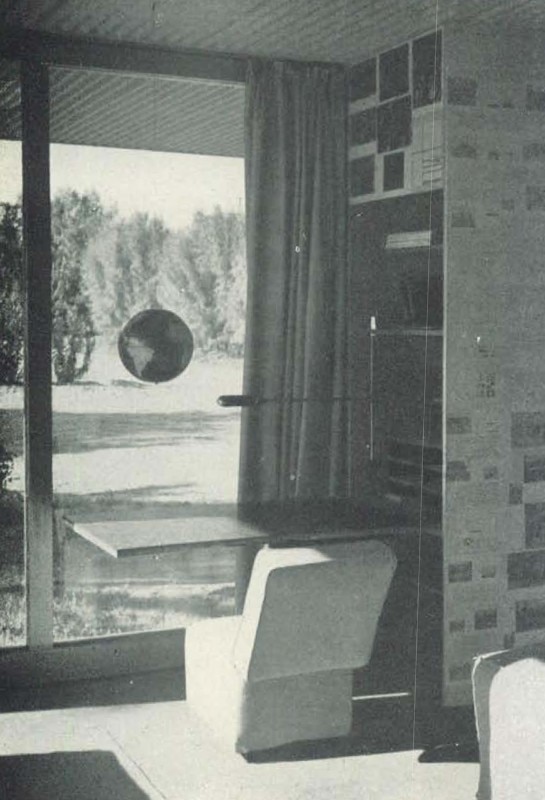

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Interior detail of the reading area. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

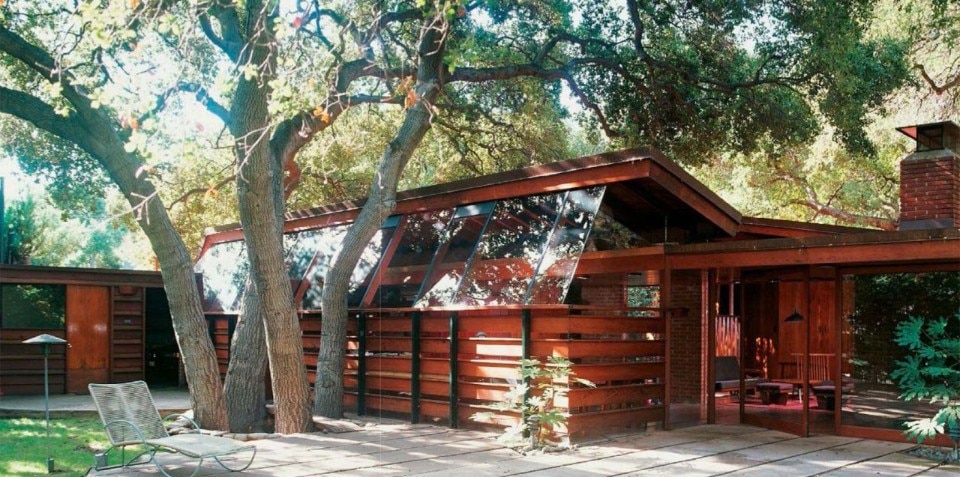

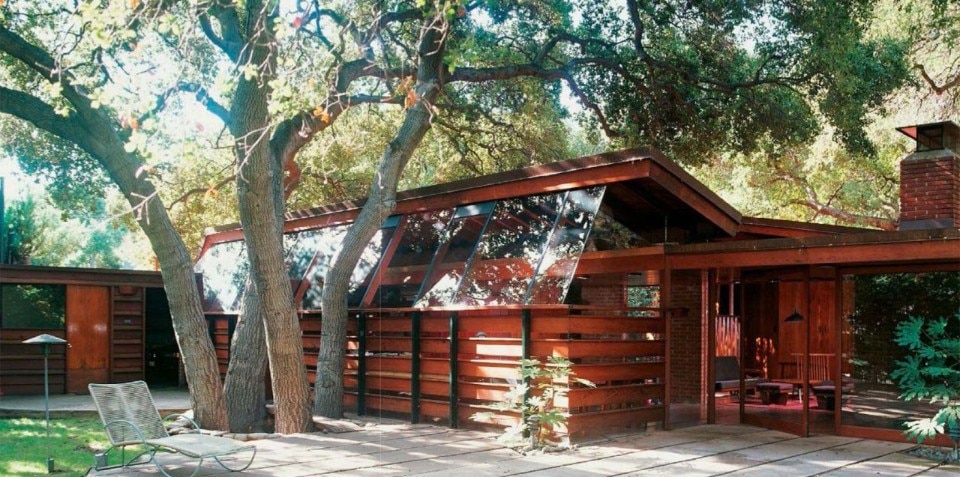

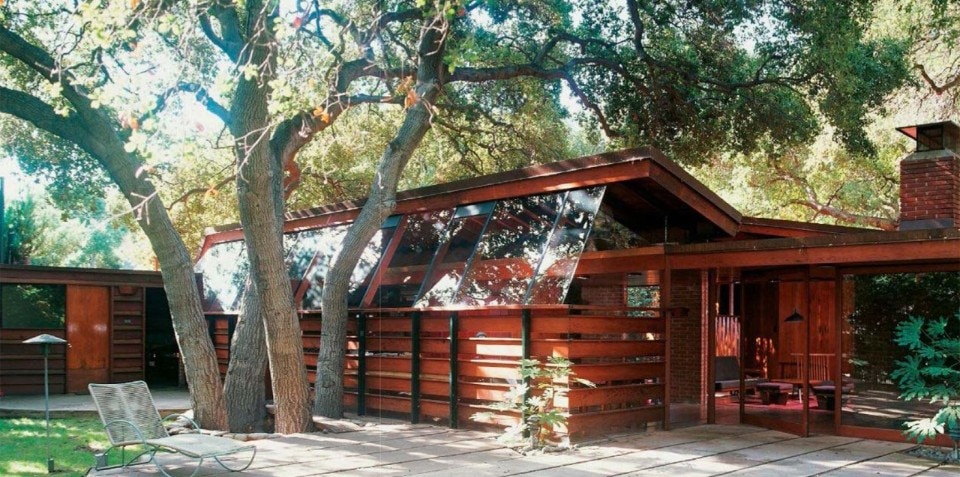

John Lautner, Schaffer Residence, Los Angeles, 1949. interior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

John Lautner, Schaffer Residence, Los Angeles, 1949. Exterior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

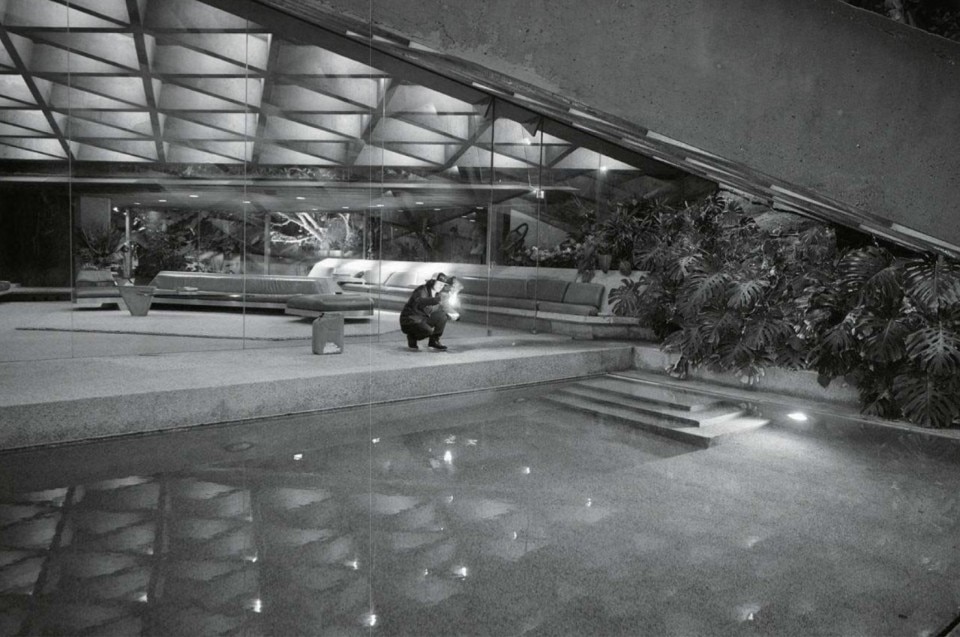

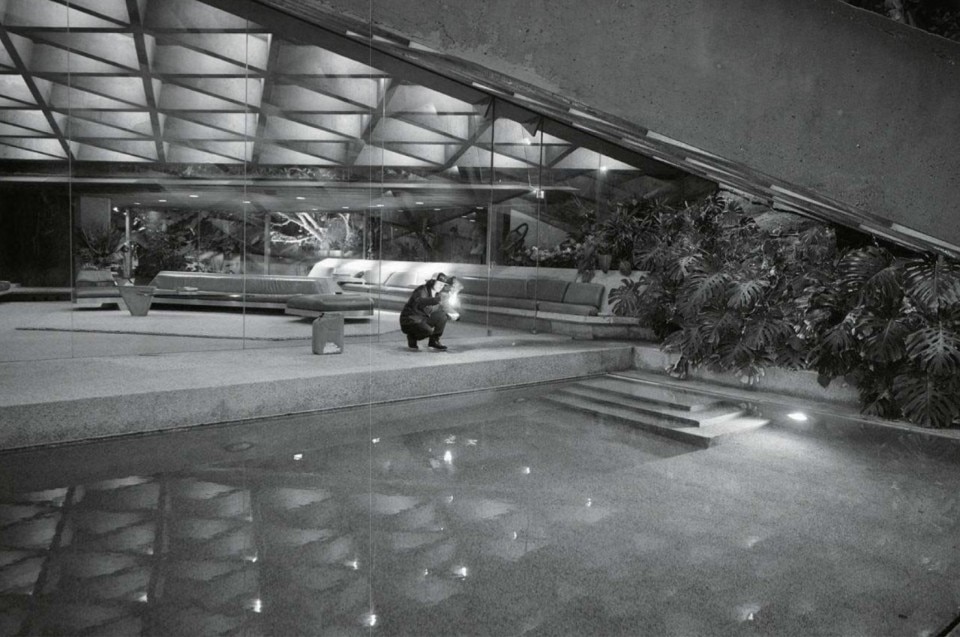

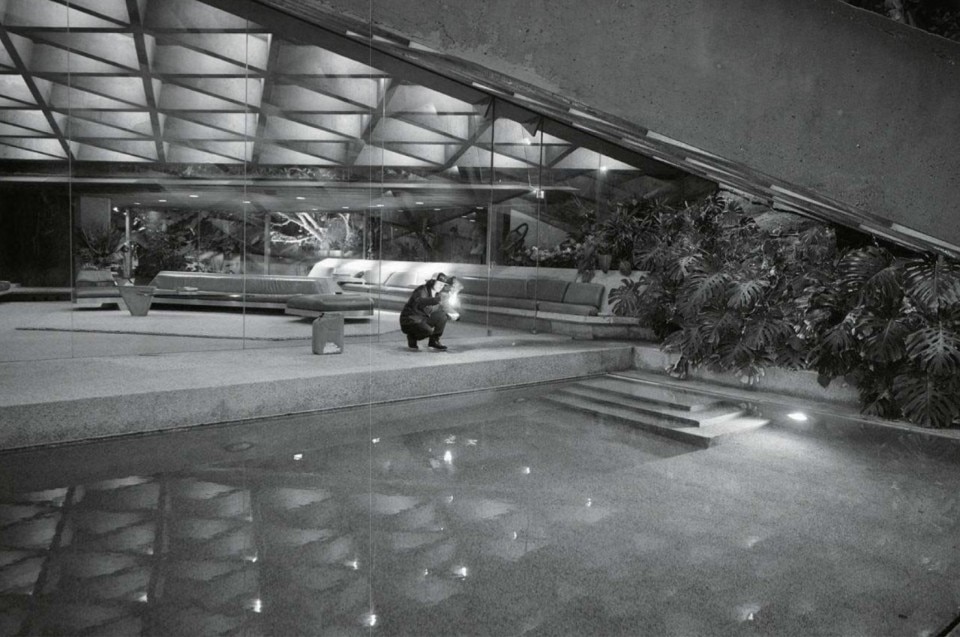

John Lautner, Sheats-Goldstein residence, Los Angeles, 1961-63. still from The Modernist by Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regent Projects LA. In Domus n.1022, March 2018

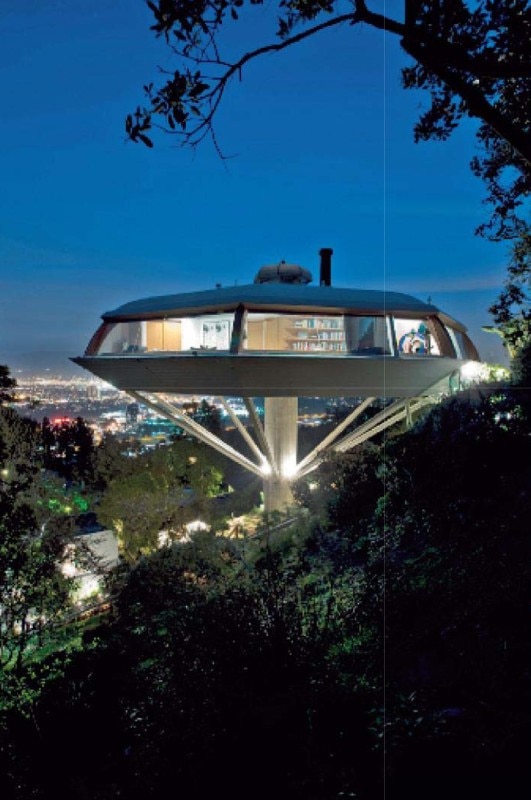

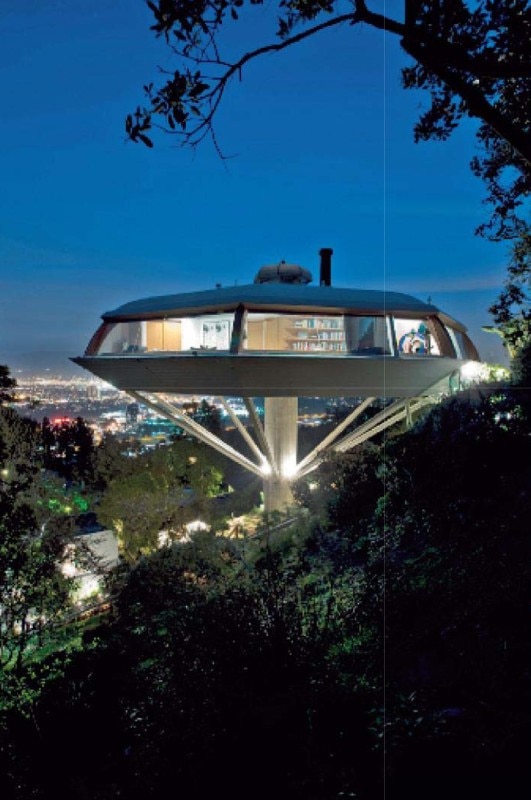

John Lautner, Malin House (Chemosphere), 1960. Exterior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

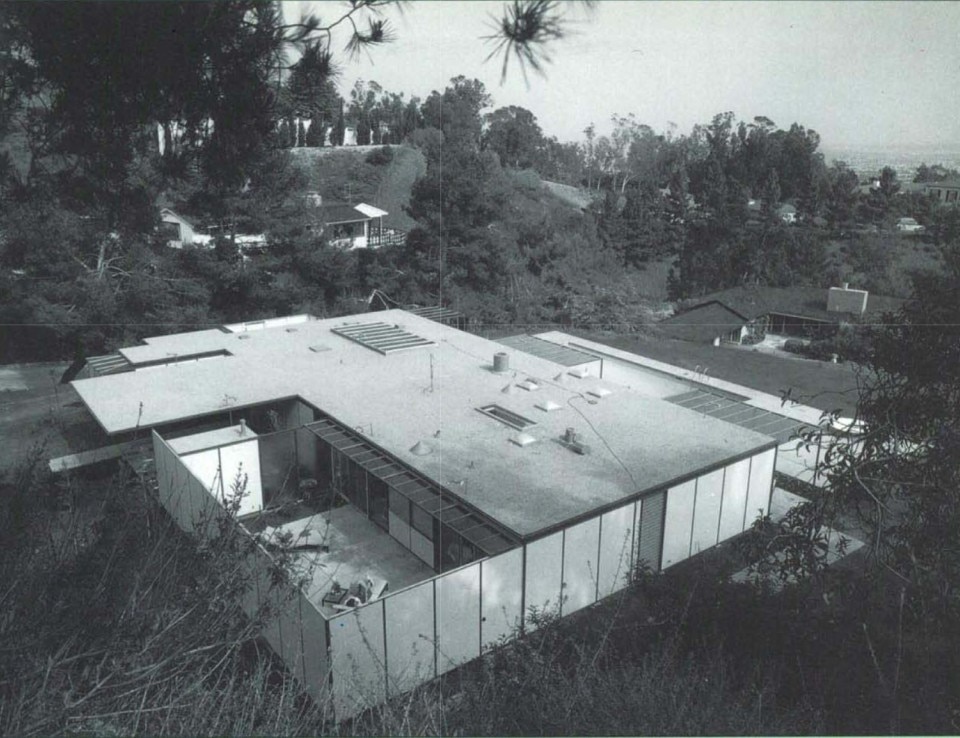

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Bird’s eye view. In Domus n.711, December 1989

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House #18 (Fields House), Beverly Hills, 1958. Plan. In Domus n.711, December 1989

Craig Ellwood, Case Study House, Los Angeles. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. View on the cantilevered living room. In Domus n.711, December 1989

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. Exterior view. In Domus n.711, December 1989

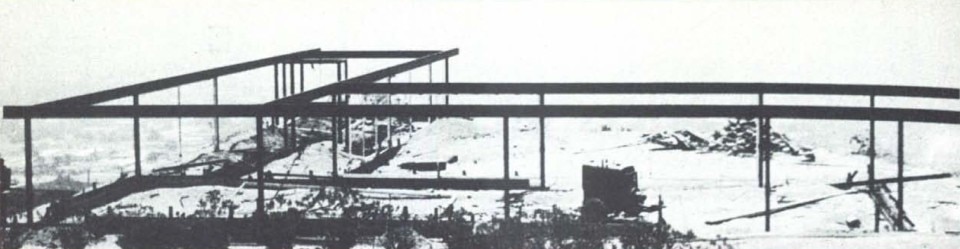

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. The steel structure under construction. In Domus n.711, December 1989

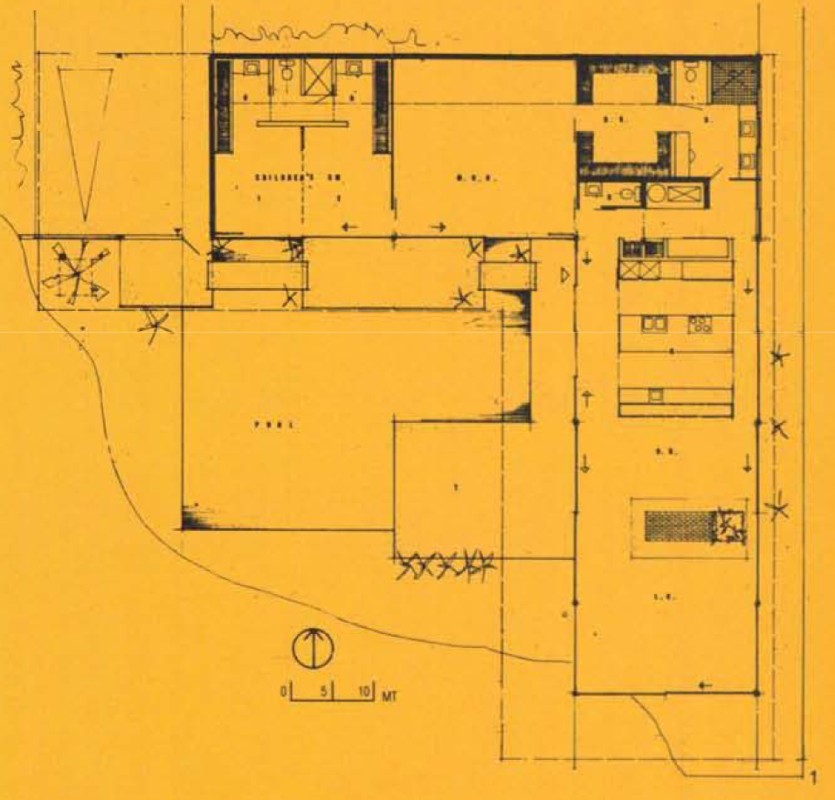

Pierre Koenig, Case Study House #22 (Stahl House), Los Angeles, 1960. Plan. In Domus n.711, December 1989

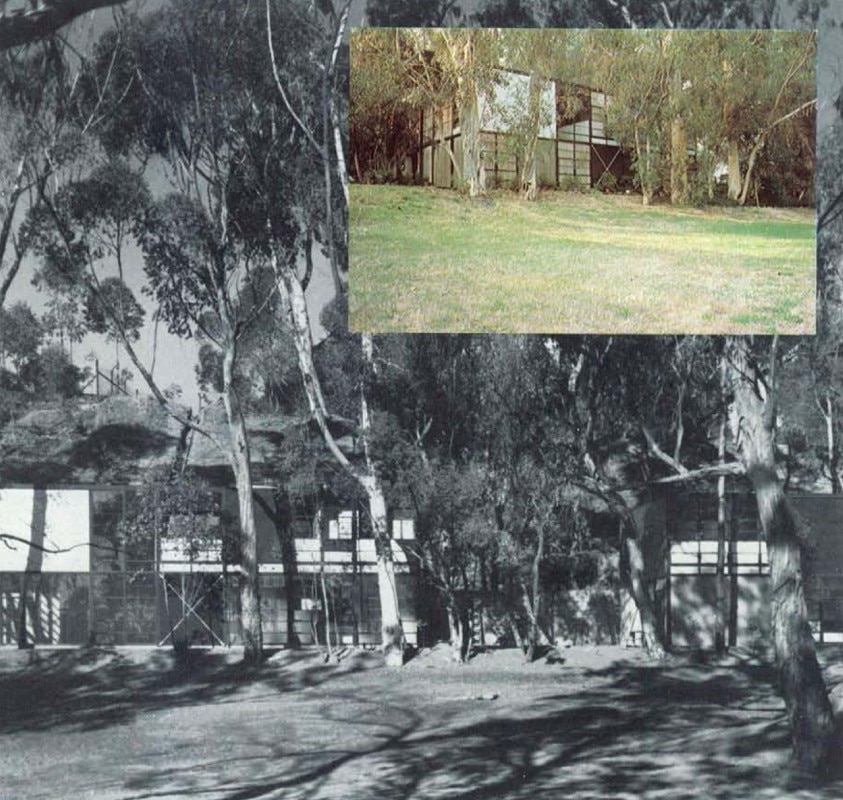

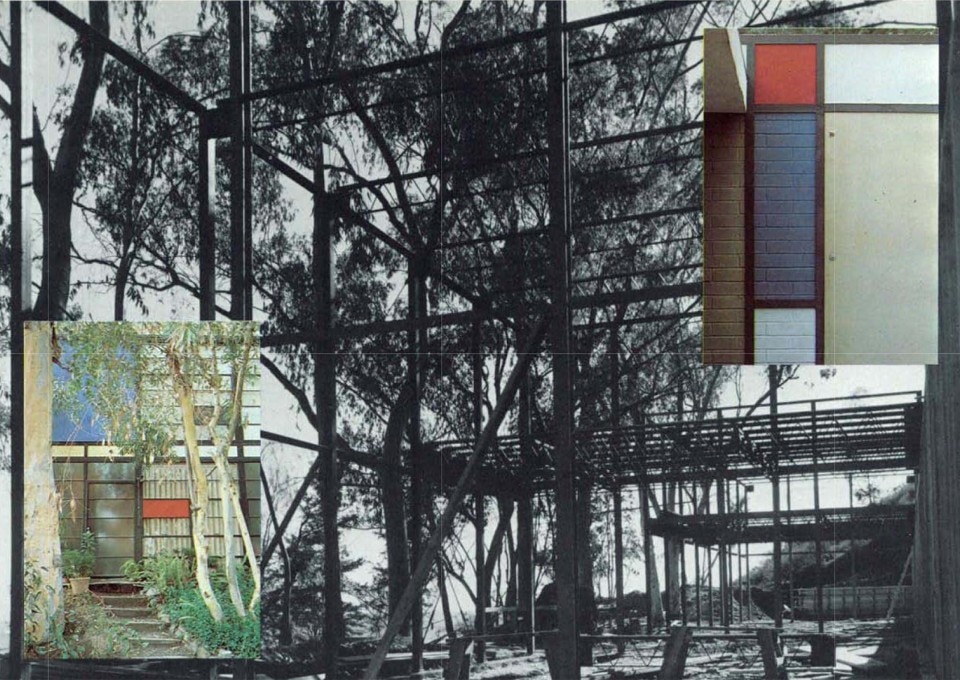

Charles and Ray Eames (with Eero Saarinen), Case Study House 8 (Eames House), 1945-49, Santa Monica, California. Exterior views. In Domus n. 614, February 1981

Charles and Ray Eames (with Eero Saarinen), Case Study House 8 (Eames House), 1945-49, Santa Monica, California. Exterior views. In Domus n. 614, February 1981

Killingswoth, Brady & Smith, Cambridge Investment inc. Building, Long Beach, 1960. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Lutah Maria Riggs, Peter Berkey III House, Carpinteria, 1961. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

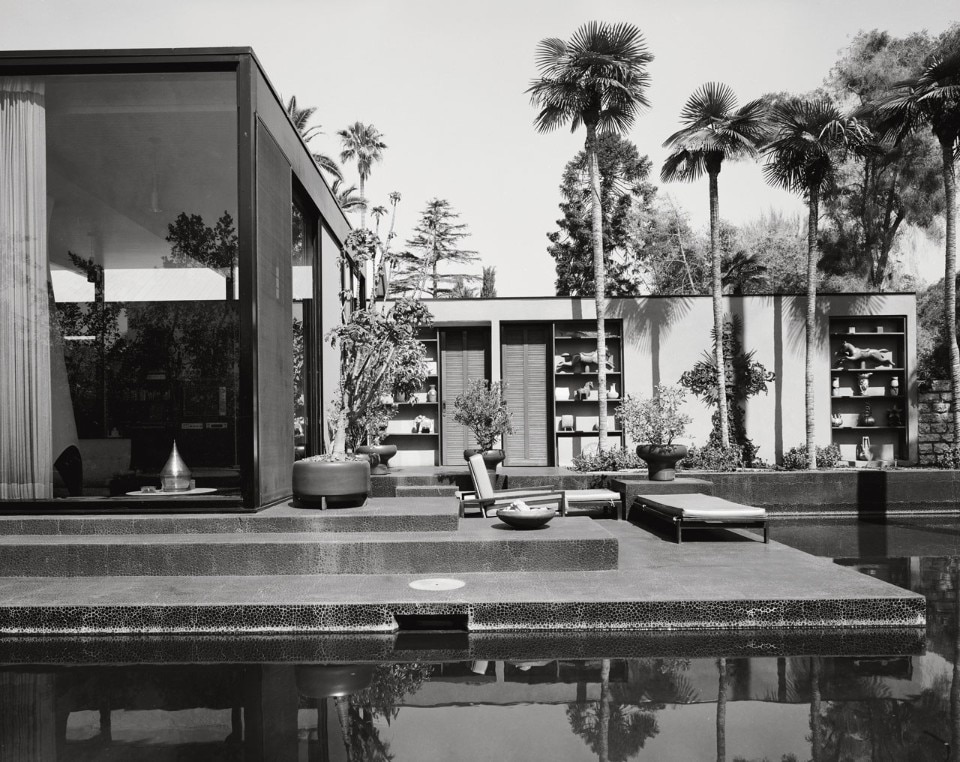

William Pereira & Associates, Pereira Residence, Los Angeles, 1964. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Killingswoth, Brady & Smith, Killingswoth, Brady & Smith office, Long Beach, 1957. Picture Credit: courtesy of the Estate of Marvin Rand

Richard J. Neutra, Windshield, view from Northwest, September 1939. Photography by Harold H. Costain. Courtesy of Special Collections, Young Library, UCLA

Richard J. Neutra, Windshield, interior view, September 1939. Photography by Harold H. Costain. Courtesy of Special Collections, Young Library, UCLA

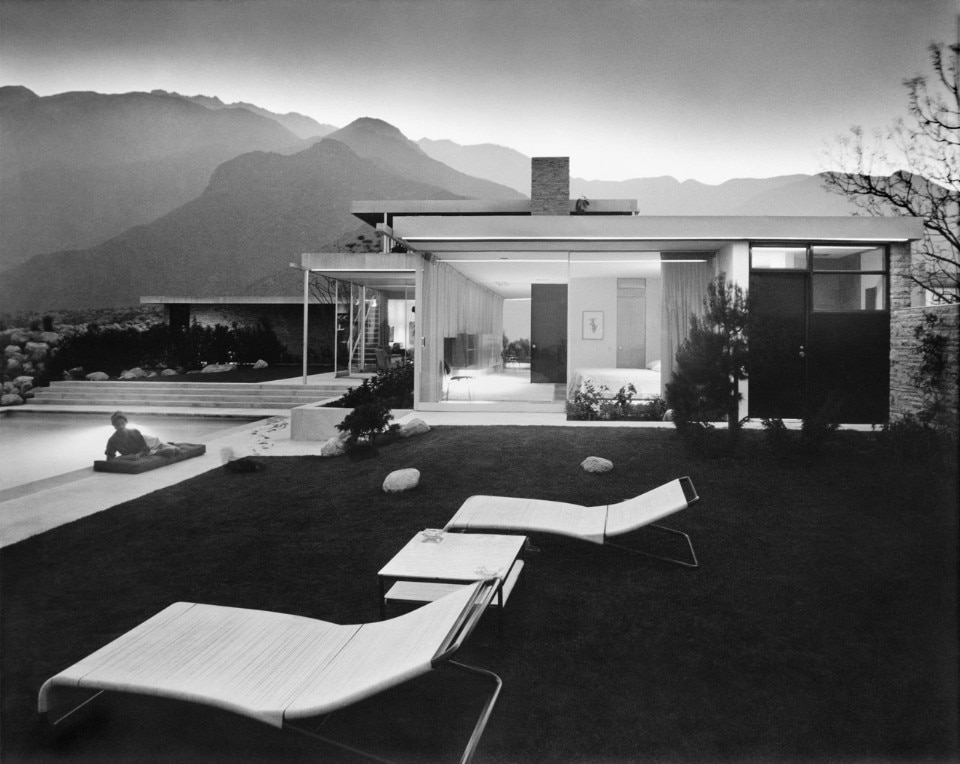

Julius Shulman, Kaufmann House designed by Richard Neutra (Palm Springs, CA), 1947. Gelatin silver print. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute. Copyright © J. Paul Getty Trust

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Exterior view. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Exterior view from the swimming pool. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

Albert Frey and John Porter Clark, Frey House I, Palm Springs, 1941. Interior detail of the reading area. In Domus n.213, settembre 1946

John Lautner, Schaffer Residence, Los Angeles, 1949. interior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

John Lautner, Schaffer Residence, Los Angeles, 1949. Exterior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

John Lautner, Sheats-Goldstein residence, Los Angeles, 1961-63. still from The Modernist by Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regent Projects LA. In Domus n.1022, March 2018

John Lautner, Malin House (Chemosphere), 1960. Exterior view. In Domus n.1014, June 2017

In January 1945, the director of Los Angeles – based magazine Arts and Architecture, John Entenza, launched the Case Study Houses program, with a first series of eight housing projects to be developed by eight American firms. The program, which lasted until 1966, had the goal to design and build prototype houses that could provide an efficient, affordable and innovative response to an exploding housing demand, fostered by the forthcoming end of the war: in other words, to innovate the typology of American single house, the very foundation of an entire culture of dwelling. In such context, figures like Craig Ellwood, Pierre Koenig and Rafael Soriano could evolve and consolidate their talent; in the first phase of the program nonetheless, afformed figures such as Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Richard Neutra were the real protagonists.

The first experimentations — soon rising to the status of icons of so-called California Modern — worked on a combination of space layout and structural solutions (mostly timber or steel frames); still related somehow to European design legacy, the buildings at Pacific Palisades stood out of this first group: Eames House (Case Study House #8, 1945-49), Entenza House (Case Study House #9, 1949) designed by the Eames with Saarinen, and the merging approach to landscape and domestic space structuring the House #20 by Neutra (1948). After 1950, Case Study House moved towards a more definite typology — almost all of them featuring a steel structure — and the most famous projects embodying the archetype of the Californa modernist house or villa appeared on the scene, like the Stahl house by Koenig with its full-height glazed envelope and its slim metal structures cantilevering on the city, or the residences by Ellwood combining proportioned sequences of open and closed parts, transparencies and opacities, constantly pursuing of an exaltation of simplicity and lightness in volumes and structures, as well as the smartness of their realization. It is the case of House #17B (1956) and Fields House (CSH #18, 1958), both in Beverly Hills.

Other figures joining the discourse of US Modernism were by the way coming from even different trajectories.

A former trainee at Le Corbusier’s studio, Albert Frey had moved to the USA in 1928; during the 40s, he left New York (where he had been working on the MoMA building) for Palm Springs, California, where , in an intermittent partnership with John Porter Clark, he became during the 50s one of the godfather of the so-called Desert Modernism, with both public buildings (Palm Springs Aerial Tramway station, 1963) and houses (Frey House I, 1947, and II, 1963): all his projects are expressing at their best those values of lightness and both technological and formal innovation characterizing the American Modernist wave.

Richard Neutra, tracing twin trajectories with his colleague and Austrian compatriot Rudolph Schindler, moved to Los Angeles from Europe before World War II, to establish there his practice and research activity. From his work with Dr. Lovell — for whom he designed the Lovell Health House in 1927 — he drew his theory of a biorealism, enriching the principles of Modern Movement with the idea of blending building, environmental and contextual elements in order to reach an complete, holistic, balance of both mental and physical health of the individual. The Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs (1946-47) is considered as the highest expression of this vision.

Neutra had had his American traineeship at Frank Lloyd Wright’s office. John Lautner instead had the chance to grow with the architect of Prairie Houses; Lautner joined the discourse of California Modern through a peculiar trajectory, starting from his education in Taliesin, the school-community founded by Wright in Arizona. Through five decades, Lautner operated an evolution of Wright’s principles of interaction between the dwelling unit (possibly centered around a solid and opaque core), environment and nature-inspired shapes, having all these components merging onto projects of houses and villas which became themselves real icons very soon. In these residences, a refined use of building technologies as both an aesthetic and a spatial principle is constantly emphasized. A series of Los Angeles projects can witness this approach, such as: the Schaffer Residence (1949), where the structure is exposed in an apparent attitude of constructive minimalism, only to provide a powerful continuum between the interiors and the surrounding environment through the wooden envelope; the Malin House, the circular Chemosphere (1960) hanging around a single central pillar; the Sheats-Goldstein Residence (1961-63), combining the practice of dwelling and the full experience of a full urban panorama, underneath an inclined monolithic concrete slab, textured by the triangular ceiling coffers of its structural layout.