Top Image: Daniel Libeskind. Photo Len Grant

Daniel Libeskind was born in Lodz, in Poland, in 1943. After moving to Israel, where he studied music, he then went first to the United States, where he graduated in Architecture at the Cooper Union in 1970, after having followed courses held by John Hejduk and Peter Eisenman, and then to England, where he specialised in History and Philosophy at Essex University. He is considered one of the most important contemporary exponents of deconstructivist architecture, a role that was recognised to him by Philip Johnson on the occasion of the exhibition “Deconstructivist Architecture”, which was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The first few years of his professional career were dedicated mainly to study and teaching. Between 1978 and 1985 he taught at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and in 1986 in Milan he founded the experimental didactic workshop “Architecture Intermedium”, which he directed until 1989, becoming a colleague and friend of Aldo Rossi.

The many destinations visited in this period include Como (where he further studied the teachings of Giuseppe Terragni and to whom he dedicated a summer course in 1988), New York, London and Venice. In this latter city, he took part in the 17th International Architecture Exhibition (1985) with a design for the planning and rationalisation of contemporary domestic space, beginning with 19th century models and summarised in the installation “House without walls”, in which the everyday living space is obtained by the assembly of irregular and fragmented lines and spaces, which was to become a characteristic trait of his creativity.

Lines and spaces which for Libeskind are a reflection of the reasons for human existence: “The problem” – he wrote – “is that of the creation of order and the recognition of order is tied to the aesthetic-moral vision of society. Thus, space is the dream of a morality formed through civil obedience”. These were concepts which had already been partially expressed in 1983 on the pages of his first publication entitled “Between Zero and Infinity”, in which the Polish architect presented an idea of architecture which was disconnected from time and which tended to dissolve within space.

I know that something needs to be constructed from some kind of material. I will use reinforced concrete and I have all my drawings, with samples of all the different materials I can use. But I don’t think that this is the substance of architecture. Architecture consists of something else. Its substance is mysterious [...] It is true, mysterious. When you are truly immersed, and you try to do it, to think about what you can construct with it, how you will do it, what will go inside.

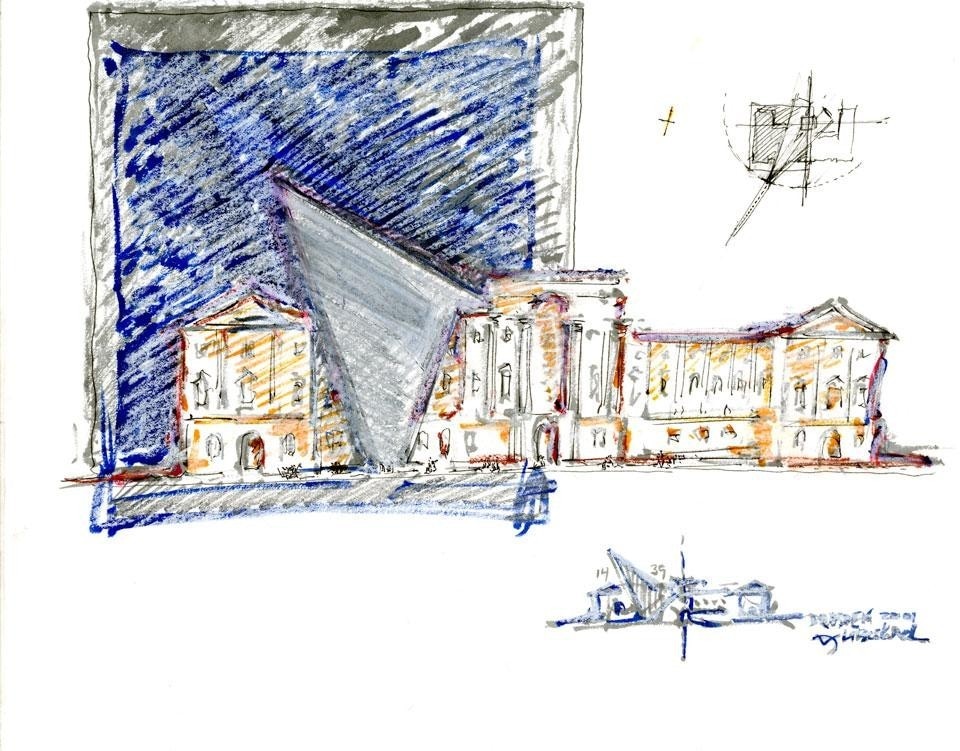

Through a text which is a veritable work of graphic design, composed of pages with a series of photomontages and drawings which set out the imaginary map of architectural experience – presented through four models: the “House-solidified light”, the “House with detached profiles”, the “Reduction model of a house under the sign of the times” and “Rebus 2” – possibly inspired by a number of Constructivist theories. Constructivism was the subject of a famous exhibition curated by Libeskind in 1988, not long before he won – in an almost completely unexpected manner – the international call for tender promoted by the IBA for the famous extension of the Jüdisches Museum in Berlin, in which two lines – one disjointed, approximately one hundred and forty metres in length, and the other, straight and uninterrupted, of 22 metres in length – cross at various points, creating spaces which are inaccessible yet clearly visible to visitors, symbolising the absence of the Berlin Jews exterminated during the Holocaust.

Narrow passageways, resembling impassable tunnels more than corridors in a public building, sudden changes in material, which generate a wide range of tactile sensations, sloping walls and beams which seem to fall onto visitors, the study of acoustics and even the absence of climatic comfort in certain areas of the building all contribute to transforming the museum into an architecture for experience, in which the invisible – or rather the tragic nature of life for Jews during the years of Nazism – becomes matter.

Many projects following the success of the Berlin example were also based on the intersection of two or more lines. These include the small gallery dedicated to Felix Nussbaum in Osnabrück (1998), the Bremen philharmonic, and the JVC University. The latter is conceived as a representation of the interweaving of logic, astronomy, mathematics and geometry – on the one hand – and between lever, heart, spine and brain on the other. Each of these entities takes shape in individual buildings assembled around the “Garden of knowledge”.

In this complex development of space – wrote Libeskind – “visitors are respected, as they are not treated as moving particles in a neutral space or as passive passengers from the past, but as participants in a visceral, intellectual and spiritual experience, a continuous discovery of the non-revealed drama of art and its history”.

The theme of the line is also central in a copious set of reflections on the city which Libeskind began in 1989 with a project known as the Multilayers Planning Process (MLPP). Here, the urban situation, in contrast to the mass of separated functional blocks which formed the foundations of rationalist urban planning, is seen as the construction of theories based on the concepts of collective sense and creativity. Examples of this are the designs for the calls for tender regarding Alexanderplatz (won by Renzo Piano) and Lansbergalle (1995) in Berlin. The first was a plan formulated around the rediscovering of the memory of existing buildings, whose forms are altered and placed in a linear park, treated as though they were ruins of the Nazi ideology that created them. The second is the design – proposing new residential buildings – of a flexible, fragmented and curved net which determines both the form and the quality of the public spaces and the open matrix of those destined for accommodation.

More recent works by Libeskind include the expansion of the Art Museum of Denver, which was completed in 2006; that for the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, inspired by the museum’s mineral collection; the Grand Canal Theatre (now known as the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre) in Dublin (2010) and the Wheel of Conscience Monument in Halifax, Canada (2011), a sculpture representing the responsibility of the country during the Shoah. He was also commissioned to project the reconstruction of the area of the ex-Twin Towers in New York and, in Italy, he won the call for tender for the re qualification of the Milan Exhibition area (in collaboration with the studies carried out by Arata Isozaki and Zaha Hadid, which is currently under way).

In the words of Attilio Terragni:

For Libeskind, architecture is a sign of that which lies beyond, expressed in a complete and organic form. It is a tactic for the expression of that which is real and invisible (and therefore is an implicit criticism of the same)

- Life period:

- 1943–alive

- Professional role:

- architect, designer, artist