Opening image: Kenzo Tange in 1981. Photo by Hans van Dijk, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Undoubtedly considered one of the main precursors of Japanese contemporary architecture, throughout his career Kenzo Tange has been able to keep together mindful formal research with an in-depth study of technology and how it influences design processes. His projects, developed between the end of World War II and the beginning of the XXI century, have been initially related to the instances of the Modern Movement that was predominant in the first half of the twentieth century, moving through the radical urban visions of the 1960s, and later up to Brutalism and Postmodern architecture.

Born in 1913 in Imabari, on the island of Shikoku, his first encounter with architecture happened with the discovery of the works of Le Corbusier, which took when Tange moved to Hiroshima in 1930. He began studying architecture at the University of Tokyo in 1935 and, after its graduation, he started his professional activity in the studio of Kunio Maekawa. The turning point in the architect’s career came in 1946: following the destruction caused by the explosion of atomic bombs in the World War II, Tange was appointed as the responsible for the reconstruction of Hiroshima. The project for the Peace Museum (built starting from 1949) dates back to this period, within which the architect achieved international fame.

Furthermore, 1946 is also important for Tange's career for another reason: this year he started teaching at the University of Tokyo and two years later he founded the Tange Laboratory (Tange kenkyūshitsu), the official name attributed to its teaching and research activities carried out until 1973. The laboratory, considered a highly experimental teaching practice between academic research and technological innovation – strongly connected with the industrial production of the time - saw the participation of architects such as Fumihiko Maki, Koji Kamiya, Arata Isozaki, Kisho Kurokawa, and Taneo Oki, first as students and later as collaborators.

Later Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki, Kisho Kurokawa, and other former students of the Tange Laboratory founded the Metabolist Movement, of which Kenzo Tange is generally considered the main precursor. The architect's analytical approach, contaminated with scientific disciplines and with great attention to technological elements, is clearly present and recognizable in the work of Metabolists. This group of architects, active between the 1960s and 1970s, developed a series of projects in which the city (and its basic cell, that is the building) is considered as a living organism capable of changing into time and change its size thanks to advanced technological solutions; the best-known project linked to the design principles of this movement is the Nagakin Capsule Tower, designed by Kishō Kurokawa. Tange’s urban-scale project more relatable to the work of the Metabolist architects is the plan for the Tokyo bay, started in 1957. The plan involved a network of expandable megastructures that develop from the center of the megalopolis to develop on the sea occupying a large area in the gulf to mitigate the problem of the dizzying increase in the population of the Japanese capital.

Another project that establishes a dialogue with the design principles of the Metabolist Movement is the Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center, built in 1967 in the Ginza district. In the broader background of this project, this city is understood as a set of modular buildings that can potentially be increased according to the use and needs of the users: the tower is made up of a cylindrical core (which contains the technical rooms and the rising elements and the side elements connected to it, inside which the offices of the press and communication agency are located.

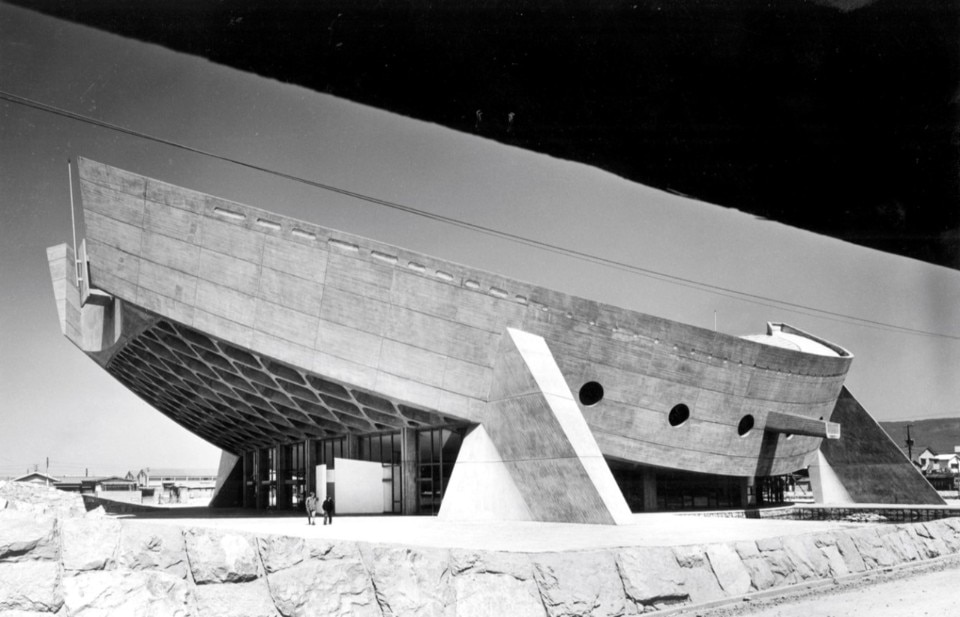

A contemporary and similar project is the Yamanashi Broadcasting and Press Center in the city of Kōfu; also in this case, the building is designed with vertical distribution cores intended as fixed elements to which "modules" with expandable and incrementable offices are connected. The greater complexity of the building program (within which the newspaper printing department, a radio station, and some television studios had to be located) is the basis of the greater planimetric complexity compared to the Shizuoka building. The third building in Tange that falls into the category of two multimedia production studios is the Fuji TV headquarters in Tokyo, built almost thirty years later than the previous ones.

In addition to experimental projects such as the mentioned, Kenzo Tange's research has also been oriented over the years towards the reinterpretation of traditional Japanese construction techniques - as in the project of the house for himself, built in 1953, the only residential building designed by Tange - and towards spatial research conducted through attention to geometry and structural issues: a clear example of this approach is the Catholic Cathedral of St. Mary in Tokyo (designed starting in 1960 and built in 1964), in which the eight load-bearing walls are shaped as hyperbolic parables defining the volume of the church and allowing its illumination through the zenith light. As in many other projects by the Japanese architect, the reinforced concrete used for the structure is juxtaposed to stainless steel that covers the roof and the bell tower of the Cathedral.

The design activity of Tange's studio also includes large-scale projects, especially related to major international events. The first relevant example is the projects carried out for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. In addition to the masterplan of the sports facilities, the project for the Yoyogi National Gymnasium should be reported, which takes up and reinterprets the volumes of modern Western architecture, in particular the Corbusierian architecture, placing it in dialogue with the Japanese context. Another large-scale project linked to a major event is the plan for Expo 1970 in Osaka: also in this case, in addition to the masterplan, Tange designed the central space of the site, the Festival Plaza. Although this large roof with a reticular structure takes up the reasoning on megastructures carried out in previous years, it is more similar to Western radical experiments (primarily Archigram's urban visions) than to the work of the Japanese Metabolists from whom Tange had progressively distanced himself.

In 1987 Kenzo Tange won the Pritzker Prize for the project of the Yoyogi National Gymnasium; after a few months, the project for the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building is shown to the public. This building, volumetrically complex and reaching a height of 243 m, is undoubtedly one of the most important buildings in his career. The construction of this building was completed in 1991 and this year the last phase of the architect's activity began, to which large interventions carried out in over 20 countries around the world belong, but which present a degree of space research and experimentation. significantly reduced compared to the projects of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. The architect died in 2005, leaving a great contribution not only to Japanese designers (Arata Isozaki and Kazuo Shinoara are just two of the famous designers strongly influenced by Tange's activity) but to the entire international architectural scenario.

In the words of Marco Biraghi:

Tange's architecture has always aimed to represent the transformations and phenomenal technological advances made by Japan in the short span of time that separates the defeat in World War II and the 1960s; while this design approach moves away from tradition understood as formal survival, on the other hand it continues to draw on an ancestral heritage, to give a Japanese identity to an industrial revolution that tends to be faceless

(Storia dell’architettura contemporanea II, 2008)

- Opening Image:

- Kenzo Tange in 1981 Photo by Hans van Dijk