Tadao Ando is one of the most famous representatives of Japanese architecture of the 20th century, and his fame has gone way beyond the confines of his country of origin. His conception of the building is based on a spatiality which evokes the typically Japanese internal world, mediated however through the application of western technology such as exposed reinforced concrete and large expanses of glass. Governed by a strong geometric aspect, his design is in fact a reflection of his experiences as an architect. A symbol of his work which is summed up by his motto:

Architecture resembles the architect

Born in Osaka in 1941, he has an artisan background – one that has provided him with detailed knowledge of the characteristics of many building materials – which is the result of having spent his youth in the glass and carpentry workshops in the Asahi district where he grew up. Self-taught, he received his first professional contract at the age of only twenty, when he was involved as an artisan in the interior design for a nightclub. He joined the Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (the Gutai Artistic Association), thanks to which he developed an interest in experimental arts rather than in traditional painting.

Between 1960 and 1969, Tadao Ando took educational journeys which led him all over Japan (to discover temples and the tea houses of Kyoto, Yokohama and Nahodka), to Moscow, to all the main European capitals and, lastly, to the United States and Africa. On returning to Japan, he set up his own studio in Osaka in 1969, transforming it first into a meeting point for young architects and – many years later – into a foundation which promotes teaching experience abroad.

The 1970s saw him involved in the design of numerous detached homes, including the Tomishima house in Osaka (1973), which later became the location of his architectural studio; the Sumiyoshi house (1976), a small terraced home that expressed Tadao Ando’s desire to reform society through architecture, a desire which emerged from the discomfort felt with regards to the inadequacy of his childhood home; and the Azuma (1979) and Koshino (1980) houses in Osaka.

These were experiences which began to express traits common to Tadao Ando’s entire production, such as the importance given to walls, fully expressed in later religious projects, and the crucial role of the sky. “In order to evade the fundamental nature of architecture as an isolated container – he said – I look to the sky as a natural element which more than any other influences architectural interiors”.

In order to evade the fundamental nature of architecture as an isolated container I look to the sky as a natural element which more than any other influences architectural interiors

In the 1980s the architect designed a series of complexes which brought him to the attention of the international scene: in 1983 he completed construction of the residential complex “Rokko I” (1978-1983), on a precipitous plot of land on the side of Mount Rokko that enjoys a view over the bay of Osoka towards Kobe. For the same location, he designed not only the later expansion works for the complex, but also, in 1986, the Chapel of the Wind, which was later followed by the Chapel of Water in Hokkaido (1988), and the Church of Light in Osaka.

The situation of the Rokka complex is decisively singular, as Tadao Ando continues to expand it in successive plots for over thirty years, and it now almost completely covers the hillside. The entire project is based on a structural grid of squares in reinforced concrete which provides the form for the independent housing units and within which an important role is played by vegetation, left free to surround the complex and artificially reflected in the vegetation covering the many panoramic terraces.

The complex is also studied to favour human interaction, based on the model of the Unitè d’Habitation seen in Marseilles during his travels through Europe, but also in the wake of Kingohusene (1957-1960) in Utzon, and the terraced complex “Søholm” (1950) by Arne Jacombsen, seen in Copenhagen.

The Church on the water (1985-1988) is set within an L-shaped wall in unfinished reinforced concrete (as is the case with the majority of the church’s vertical surfaces), which surrounds it, and which leads the gaze to the artificial lake over which it looks. The layout is made up of two overlapping squares, with the smaller of the two containing four crosses whose extremities touch.

The relationship with the water is the key to the interpretation of many other designs, including the “Time’s I” shopping centre on the banks of the Takase river and designed to resemble a boat. The following year, Tadao Ando received his first international award, the Alvar Aalto medal presented to him by the National Association of Finnish Architects.

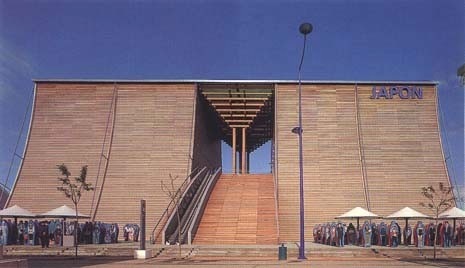

The 1990s were characterised by important commissions including the design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Naoshima (1988-1992); the Temple on the Water in Hompuku-ji in Hyogo (1989-1991), built around an artificial water basin reserved for the cultivation of lotus, the surface of which is crossed by a walkway leading to the access stairs to the internal plots; the Japanese Pavilion at the Seville Expo (1989-1992), which re-interpreted traditional wooden architecture through contemporary technology.

The headquarters of the Pulitzer Foundation for Arts in St. Louis, Missouri (1991-2001); the Benetton Research Centre for Communication named “Fabrica” (1992-200), built in Treviso around a 16th century Palladian Villa that was restored and subjected to conservation works and which became the focal point for the entire complex, built into the ground in order to not disturb the environmental balance of the setting; the Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (1997-2002), which once again saw the use of an artificial lake reflecting the large expanses of glass and the overhanging flat roof in reinforced concrete supported by a series of Y-shaped pillars.

The theme of the detached Japanese house, never abandoned, was once again a central theme in the 2000s, thanks to projects such as the 4x4 house in Hyogo (2001-2003), a small tower in reinforced concrete which looked out over the Inland Sea and which examined the theme of reduction to the minimum of living space imposed by the scarce amount of land available.

Over the course of his career, Ando has often collaborated with his twin brother, Takao Kitayama, a successful developer in the sector of avant-garde shopping centres.

The many awards presented to Tadao Ando include the Japanese Grand Prix for Art in 1994, and the Pritzker Prize the following year. He has acted as visiting professor at Yale, Harvard and Columbia Universities (1987-1990).

In the words of Masao Furuyama:

Ando’s architecture joins simplicity of form to complexity of space, using materials which are pleasant to touch. It presents a clear and critical image through simple forms favoured by the geometry of the spaces. It always expresses an audacious proposal of life or an element of social criticism. [...] But Ando’s architecture is not minimalist: it is true that it is based on unadorned boxes, but the bare walls stir the imagination and the empathy of the observer through their very nudity.

Opening image: Photo Studio Casali – Domus Archives

- Born:

- 1941

- Professional role:

- architect, designer