According to the New York Times and the Oxford English Dictionary, the word that defined 2025 was “rage bait”: online content designed to trigger anger and polarization. For the Cambridge Dictionary it is “parasocial”, referring to increasingly close – and often toxic – relationships between stars and the public. In Italy, for Treccani, the word of the year is “trust”.

Three different definitions, but a shared impression: 2025 was marked by a widespread sense of online disorientation. There is too much content, constant stimulation, while the tools to orient oneself and to select remain few.

In this scenario, rereading becomes an almost countercultural act. Not out of nostalgia, but as a way to orient oneself. Because if 2025 was the year of content designed to trigger immediate reactions, Domus continued to do what it has always done: build stories that do not ask to be consumed quickly.

This selection of twenty articles, to linger over for the first time or to reread during the holidays, comes about in this way: as a pause in the flow. It is an invitation to return to architectures that no longer exist and to others that endure over time; to real cities and to the unsettling ones of digital crime; to humble objects and furnishings that shaped the history of the twentieth century. There is desire in the sets of Luca Guadagnino, there is the distorted intimacy of Instagram feeds, there are “magical” places that become reality like those of Elmgreen & Dragset, and those that have remained only in the imagination of designers.

And there is one question that runs through the entire year: what does it mean today to design – a space, an object, even a face – in a world that moves faster than our ability to understand it?

Carlo Scarpa's other store: the rebirth of a long-forgotten project in Bologna

View gallery

View gallery

Everyone knows Carlo Scarpa's famous Olivetti store in Piazza San Marco. However, few people are aware that in 1961, the architect also collaborated with Dino Gavina on another store which, although less well known, is equally fascinating. Today, we returned to visit it after its restoration and reopening. Read more

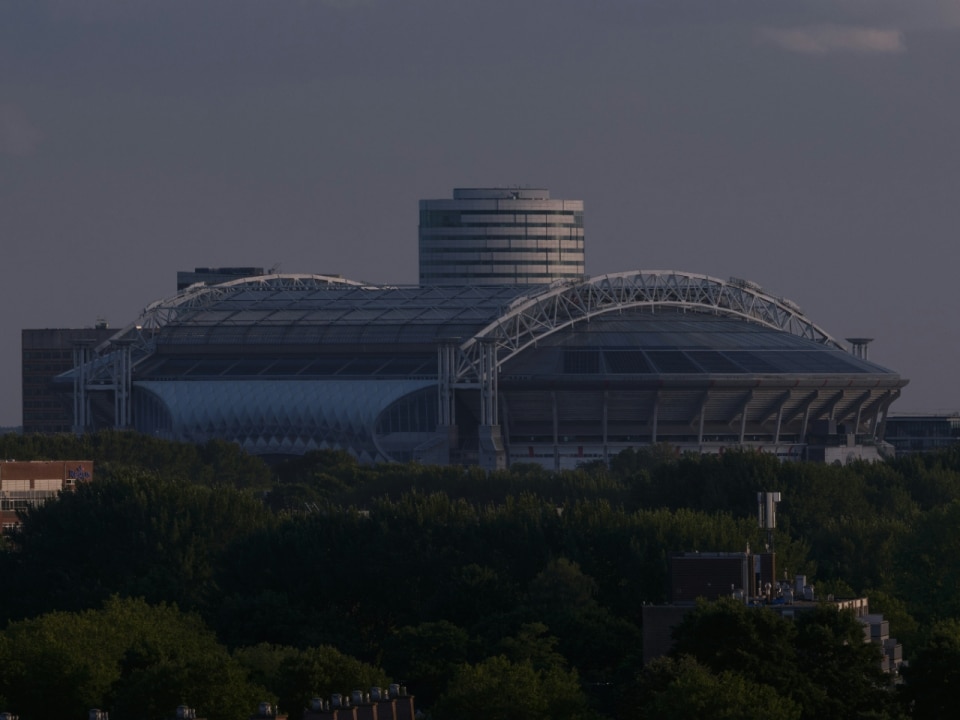

The most famous stadiums that no longer exist

View gallery

View gallery

Arsenal Stadium, Highbury, London

It is said that the English invented football – and, inevitably, they were among the first to define the standards of the modern ground. One name stands out in this early history: the Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, whose work between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries shaped the evolution of British sporting architecture. His designs formed the foundations of legendary venues such as Craven Cottage (Fulham), Anfield (Liverpool), Goodison Park (Everton), Molineux (Wolverhampton Wanderers), Villa Park (Aston Villa), White Hart Lane (Tottenham Hotspur), and Stamford Bridge (Chelsea), among many others.

Several of his creations, however, have been lost, including West Ham Stadium in London, demolished in 1972. With its unusual elliptical plan and running track – rare in British football – it also hosted greyhound races and speedway events.

Among Leitch’s most distinctive works was the Arsenal Stadium, better known as Highbury. Built in 1913, it underwent several renovations, including the 1930s intervention that gave the East and West Stands their unmistakable Art Deco façade. When Arsenal moved to the new Emirates Stadium in 2006, Highbury was converted into Highbury Square, a residential complex with the former pitch turned into a central garden.

Protected as a listed building, the two main stands were preserved, while the beloved North Bank and Clock End are now entirely gone.

Photo CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stadio Flaminio, Rome

Pier Luigi Nervi was one of the foremost figures of Italy’s post-war structural modernism. His monumental works – from the Torino Esposizioni complex to the Hall of the Papal Audiences in the Vatican, and the Pirelli Tower in Milan with Gio Ponti – stand as milestones of Italian engineering and design.

Sport was another vital field of experimentation for Nervi. Among his many works are the Stadio Artemio Franchi in Florence and, with his son Antonio, the Stadio Flaminio in Rome. Inaugurated in 1959, the Flaminio could seat around 50,000 spectators and also contained four gyms, a swimming pool, bars, changing rooms, a first-aid centre, and state-of-the-art facilities.

The stadium was at the heart of the cluster of buildings designed for the 1960 Rome Olympics, embodying the elegance and dynamism of the Italian modernist spirit – most strikingly in the sinuously-shaped concrete cover of its main stand.

On top of hosting matches for both AS Roma and SS Lazio, it was the home of the Italian rugby national team until 2011, after which it fell into neglect and decay. In 2017, the stadium was officially listed for protection: a small but hopeful step towards the restoration it urgently needs before it becomes beyond repair.

De Meer Stadion, Amsterdam

Rembrandt, fries, coffee shops, and Johan Cruijff: that’s Amsterdam in a nutshell for the uninitiated. Since 2018, the late Dutch striker has lent his name to the city’s modern stadium, the Johan Cruijff Arena. Before its construction, Ajax played at De Meer Stadion, itself the successor to the older Het Houten Stadion, demolished in 1935.

De Meer was the stage for Ajax’s golden years: the era of Cruijff, Rinus Michels, and ‘total football’, the revolutionary style of play that in the early 1970s earned the Netherlands the nickname Clockwork Orange. Closed in 1996 because its 19,600 seats no longer met the club’s ambitions, De Meer was soon demolished, becoming one of football’s most celebrated lost theatres.

Stadio Silvio Appiani, Padua

The Stadio Appiani, home to Calcio Padova from 1924 to 1994, remains one of the most atmospheric venues in Italian football history. Nicknamed the lions’ den for the intensity created by its stands pressed so close to the pitch, the stadium’s character was defined by the backdrop of the Church of Misericordia’s bell tower and the adjoining monastery – a quintessentially Italian touch. In contrast stood its English-style gable roof on the main stand, later removed and now lost.

The story of the Appiani – not demolished but left tragically idle – is a deeper one about the social meaning a stadium can hold for its community. The Stadio Euganeo, where Padova has played since 1994, is widely disliked by supporters, who find it soulless and detached from the club’s identity. Adding to the discontent are the continuous structural and bureaucratic mishaps – almost comically Italian in their persistence. In recent seasons, the Curva Sud has even been closed to the public following a judicial seizure linked to renovation works.

Photo from the book Nella fossa dei leoni (In the lions' den). The Appiani stadium in Padua in the memories and recollections of many former Biancoscudati players, p. 243, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Griffin Park, London

There are stadiums with greater sporting pedigree than Griffin Park, the former home of Brentford FC in west London. Yet few carried its unique charm. Known as Fortress Griffin Park for hosting the longest home winning streak in English football (21 games in the 1929–30 season), it left a mark far beyond architecture.

Griffin Park also held a world record: it was the only stadium in the world with a pub on each corner – a legacy of its proximity to the Fuller’s Brewery, whose griffin symbol lent the ground its name. The stadium was demolished in 2021, only a few years after the historic brewery itself was acquired by Japan’s Asahi Group.

The story of Griffin Park is, in the end, a broader reflection on how football mirrors the social and urban transformations of a city. It echoes, in some ways, the fate of another brewery-linked ground: Stadio Moretti in Udine, demolished in 1998 and named after the local beer producer. One of its final appearances lives on in Italian pop culture as a filming location for L’allenatore nel pallone (1984), a cult football comedy starring Lino Banfi.

Courtesy en.namu.wiki

Arena da Amazônia, Manaus

Not all stadiums that fall into ruin are historic. Another central theme in the discourse on sports architecture is that of the so-called white elephants: buildings that are enormously expensive to build and maintain, yet remain largely unused. Some of the stadiums erected for the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil are textbook examples. Among them, the Arena da Amazônia in Manaus stands out. Costing over $200 million, it now lies, little more than a decade later, in a state of abandonment and decay. One of the main reasons for its underuse is the absence of local football clubs with a fan base large enough to sustain attendance and upkeep.

To offset maintenance costs, the stadium has been partially repurposed hosting wedding receptions. In its own peculiar way, a form of adaptive reuse.

Photo Governo do Brasil - Portal da Copa, CC BY 3.0 br, via Wikimedia Commons

Estadio Pocitos, Montevideo

Speaking of World Cups: the first goal in FIFA World Cup history was scored here, in 1930, by France’s Lucien Laurent against Mexico. The Estadio Pocitos in Montevideo, Uruguay – once home of Club Atlético Peñarol – is considered one of the most influential venues in the history of sports architecture, thanks to its elliptical stands inspired by ancient Greek theatres.

Decommissioned in 1933 and demolished as early as 1940, the stadium’s fate was sealed by the high urban density of Montevideo, which made expansion impossible. This makes it an illuminating early case study of an issue that remains pressing to this day – as exemplified by the ongoing debate surrounding San Siro.

Photo por https://cdf.montevideo.gub.uy/catalogo/foto/03079fmhge, Dominio público, via Wikimedia Commons

Arsenal Stadium, Highbury, London

It is said that the English invented football – and, inevitably, they were among the first to define the standards of the modern ground. One name stands out in this early history: the Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, whose work between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries shaped the evolution of British sporting architecture. His designs formed the foundations of legendary venues such as Craven Cottage (Fulham), Anfield (Liverpool), Goodison Park (Everton), Molineux (Wolverhampton Wanderers), Villa Park (Aston Villa), White Hart Lane (Tottenham Hotspur), and Stamford Bridge (Chelsea), among many others.

Several of his creations, however, have been lost, including West Ham Stadium in London, demolished in 1972. With its unusual elliptical plan and running track – rare in British football – it also hosted greyhound races and speedway events.

Among Leitch’s most distinctive works was the Arsenal Stadium, better known as Highbury. Built in 1913, it underwent several renovations, including the 1930s intervention that gave the East and West Stands their unmistakable Art Deco façade. When Arsenal moved to the new Emirates Stadium in 2006, Highbury was converted into Highbury Square, a residential complex with the former pitch turned into a central garden.

Protected as a listed building, the two main stands were preserved, while the beloved North Bank and Clock End are now entirely gone.

Photo CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stadio Flaminio, Rome

Pier Luigi Nervi was one of the foremost figures of Italy’s post-war structural modernism. His monumental works – from the Torino Esposizioni complex to the Hall of the Papal Audiences in the Vatican, and the Pirelli Tower in Milan with Gio Ponti – stand as milestones of Italian engineering and design.

Sport was another vital field of experimentation for Nervi. Among his many works are the Stadio Artemio Franchi in Florence and, with his son Antonio, the Stadio Flaminio in Rome. Inaugurated in 1959, the Flaminio could seat around 50,000 spectators and also contained four gyms, a swimming pool, bars, changing rooms, a first-aid centre, and state-of-the-art facilities.

The stadium was at the heart of the cluster of buildings designed for the 1960 Rome Olympics, embodying the elegance and dynamism of the Italian modernist spirit – most strikingly in the sinuously-shaped concrete cover of its main stand.

On top of hosting matches for both AS Roma and SS Lazio, it was the home of the Italian rugby national team until 2011, after which it fell into neglect and decay. In 2017, the stadium was officially listed for protection: a small but hopeful step towards the restoration it urgently needs before it becomes beyond repair.

De Meer Stadion, Amsterdam

Rembrandt, fries, coffee shops, and Johan Cruijff: that’s Amsterdam in a nutshell for the uninitiated. Since 2018, the late Dutch striker has lent his name to the city’s modern stadium, the Johan Cruijff Arena. Before its construction, Ajax played at De Meer Stadion, itself the successor to the older Het Houten Stadion, demolished in 1935.

De Meer was the stage for Ajax’s golden years: the era of Cruijff, Rinus Michels, and ‘total football’, the revolutionary style of play that in the early 1970s earned the Netherlands the nickname Clockwork Orange. Closed in 1996 because its 19,600 seats no longer met the club’s ambitions, De Meer was soon demolished, becoming one of football’s most celebrated lost theatres.

Stadio Silvio Appiani, Padua

The Stadio Appiani, home to Calcio Padova from 1924 to 1994, remains one of the most atmospheric venues in Italian football history. Nicknamed the lions’ den for the intensity created by its stands pressed so close to the pitch, the stadium’s character was defined by the backdrop of the Church of Misericordia’s bell tower and the adjoining monastery – a quintessentially Italian touch. In contrast stood its English-style gable roof on the main stand, later removed and now lost.

The story of the Appiani – not demolished but left tragically idle – is a deeper one about the social meaning a stadium can hold for its community. The Stadio Euganeo, where Padova has played since 1994, is widely disliked by supporters, who find it soulless and detached from the club’s identity. Adding to the discontent are the continuous structural and bureaucratic mishaps – almost comically Italian in their persistence. In recent seasons, the Curva Sud has even been closed to the public following a judicial seizure linked to renovation works.

Photo from the book Nella fossa dei leoni (In the lions' den). The Appiani stadium in Padua in the memories and recollections of many former Biancoscudati players, p. 243, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Griffin Park, London

There are stadiums with greater sporting pedigree than Griffin Park, the former home of Brentford FC in west London. Yet few carried its unique charm. Known as Fortress Griffin Park for hosting the longest home winning streak in English football (21 games in the 1929–30 season), it left a mark far beyond architecture.

Griffin Park also held a world record: it was the only stadium in the world with a pub on each corner – a legacy of its proximity to the Fuller’s Brewery, whose griffin symbol lent the ground its name. The stadium was demolished in 2021, only a few years after the historic brewery itself was acquired by Japan’s Asahi Group.

The story of Griffin Park is, in the end, a broader reflection on how football mirrors the social and urban transformations of a city. It echoes, in some ways, the fate of another brewery-linked ground: Stadio Moretti in Udine, demolished in 1998 and named after the local beer producer. One of its final appearances lives on in Italian pop culture as a filming location for L’allenatore nel pallone (1984), a cult football comedy starring Lino Banfi.

Courtesy en.namu.wiki

Arena da Amazônia, Manaus

Not all stadiums that fall into ruin are historic. Another central theme in the discourse on sports architecture is that of the so-called white elephants: buildings that are enormously expensive to build and maintain, yet remain largely unused. Some of the stadiums erected for the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil are textbook examples. Among them, the Arena da Amazônia in Manaus stands out. Costing over $200 million, it now lies, little more than a decade later, in a state of abandonment and decay. One of the main reasons for its underuse is the absence of local football clubs with a fan base large enough to sustain attendance and upkeep.

To offset maintenance costs, the stadium has been partially repurposed hosting wedding receptions. In its own peculiar way, a form of adaptive reuse.

Photo Governo do Brasil - Portal da Copa, CC BY 3.0 br, via Wikimedia Commons

Estadio Pocitos, Montevideo

Speaking of World Cups: the first goal in FIFA World Cup history was scored here, in 1930, by France’s Lucien Laurent against Mexico. The Estadio Pocitos in Montevideo, Uruguay – once home of Club Atlético Peñarol – is considered one of the most influential venues in the history of sports architecture, thanks to its elliptical stands inspired by ancient Greek theatres.

Decommissioned in 1933 and demolished as early as 1940, the stadium’s fate was sealed by the high urban density of Montevideo, which made expansion impossible. This makes it an illuminating early case study of an issue that remains pressing to this day – as exemplified by the ongoing debate surrounding San Siro.

Photo por https://cdf.montevideo.gub.uy/catalogo/foto/03079fmhge, Dominio público, via Wikimedia Commons

The stadiums that have shaped the history of football — both in sporting and architectural terms — are now abandoned or demolished. The recent controversy surrounding Milan’s San Siro has reignited a debate on Italian stadiums that extends to those across the globe. Read more

5 absurd objects that tried to change the future

Between technical utopia and an obsession with control, these five inventions, each designed to improve everyday life, reveal the most unsettling – and oddly fascinating – side of modern design. Read more

Scam Cities: inside the urban infrastructures of digital crime

In Southeast Asia, urban clusters designed for online fraud are emerging: camouflaged, functional spaces where architecture becomes the real infrastructure of the dark side of the web. Read more

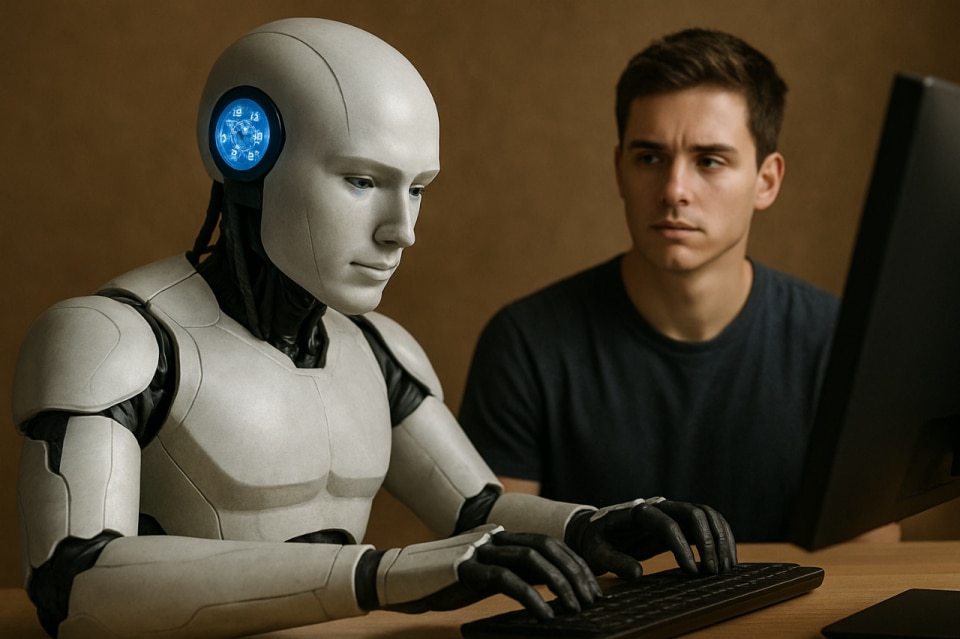

Artificial intelligence is starting to steal our jobs

According to a survey by the World Economic Forum, 41% of employers are already planning to reduce their workforce in favor of AI. However, the consequences are quite different from what we expected, and they mainly affect the younger generations. Read more

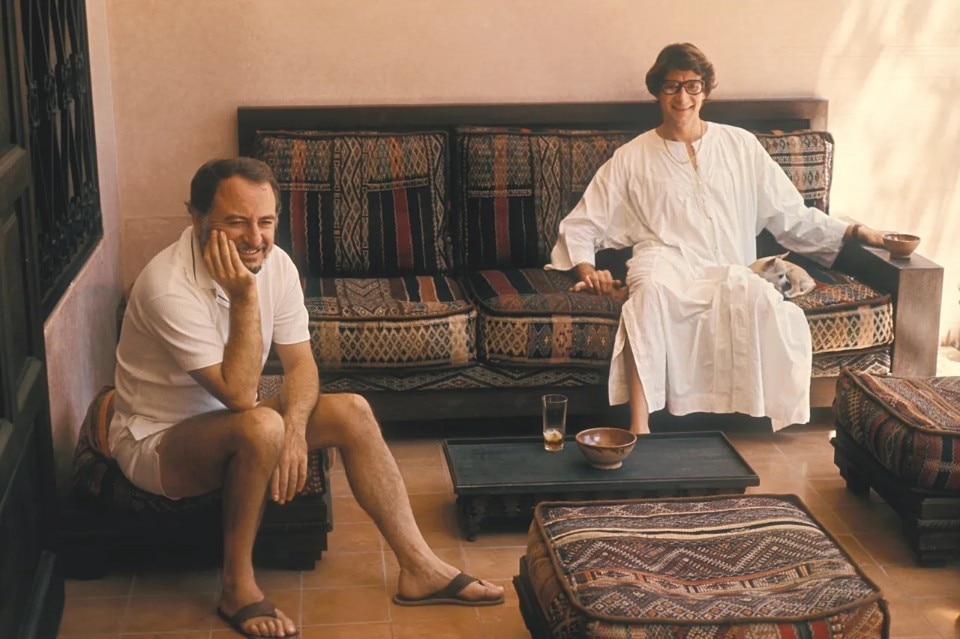

Yves Saint Laurent’s Morocco: tracing the places of a lasting love

In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé discovered Morocco and fell in love with the country. Marrakech became a creative refuge and source of inspiration, marking the beginning of a bond that would forever shape his life and artistic vision. Read more

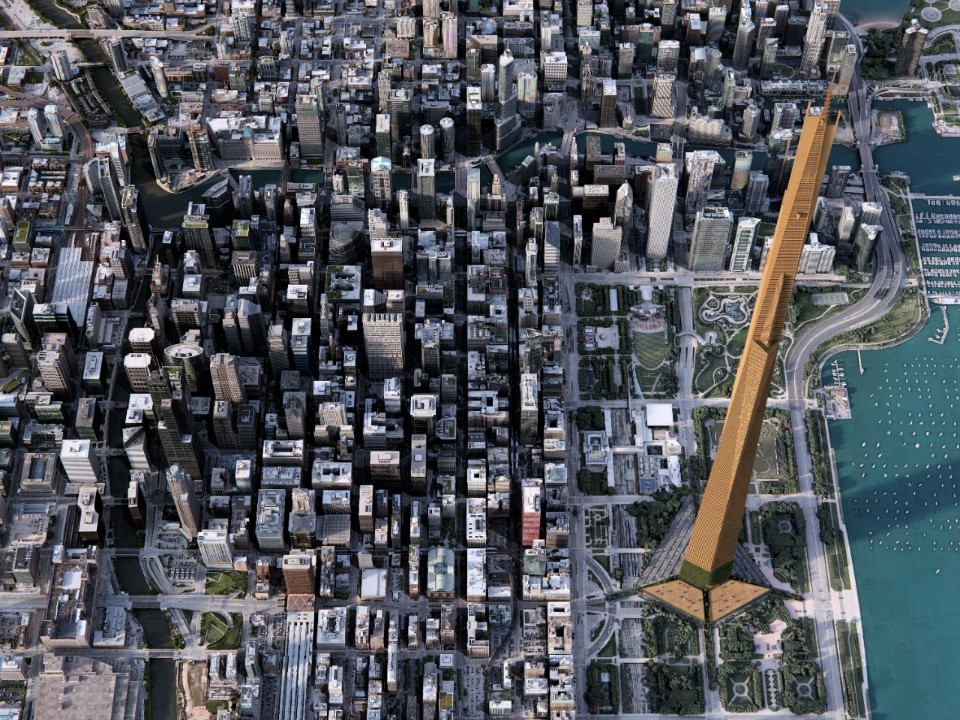

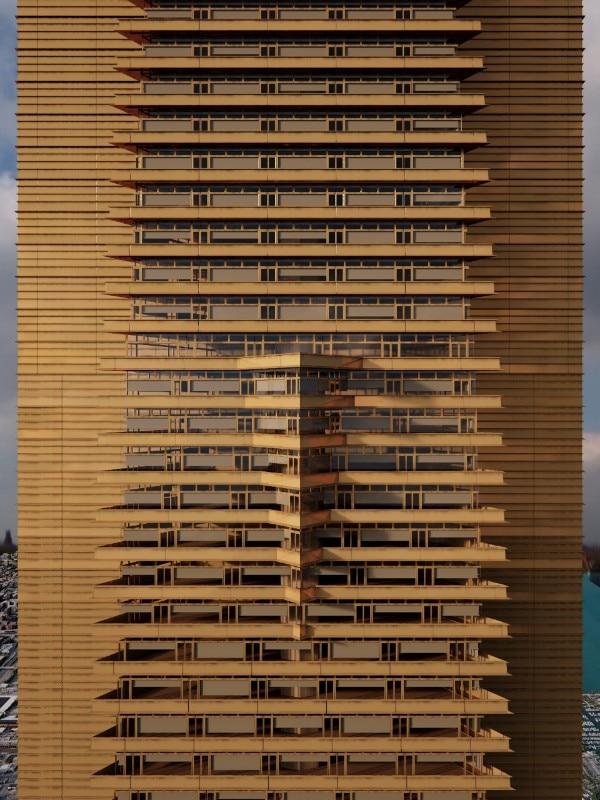

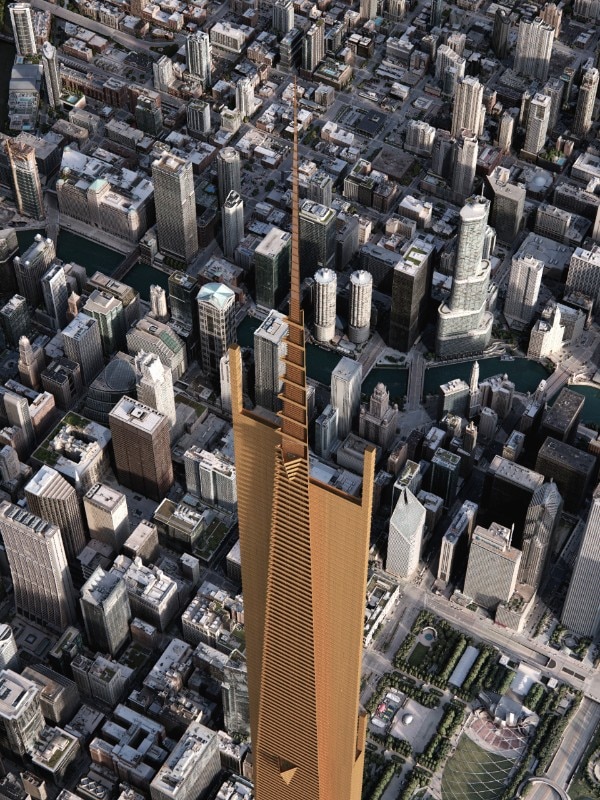

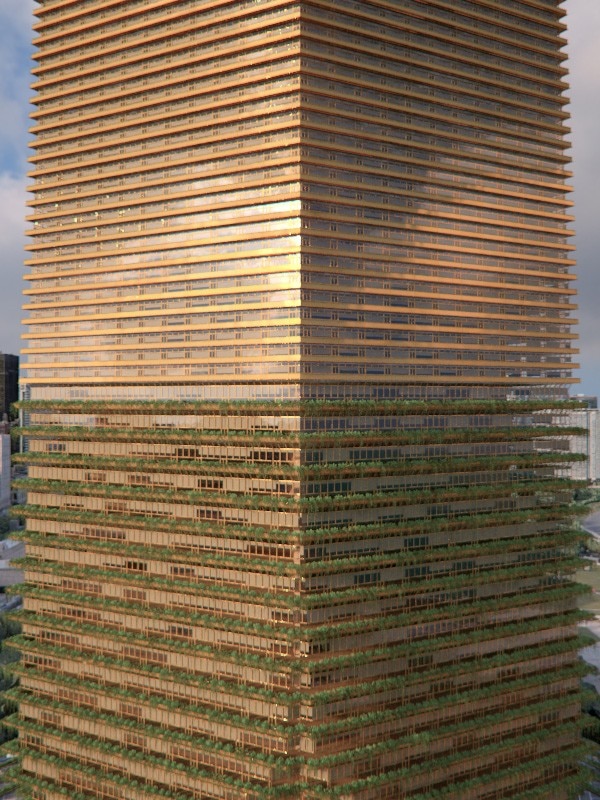

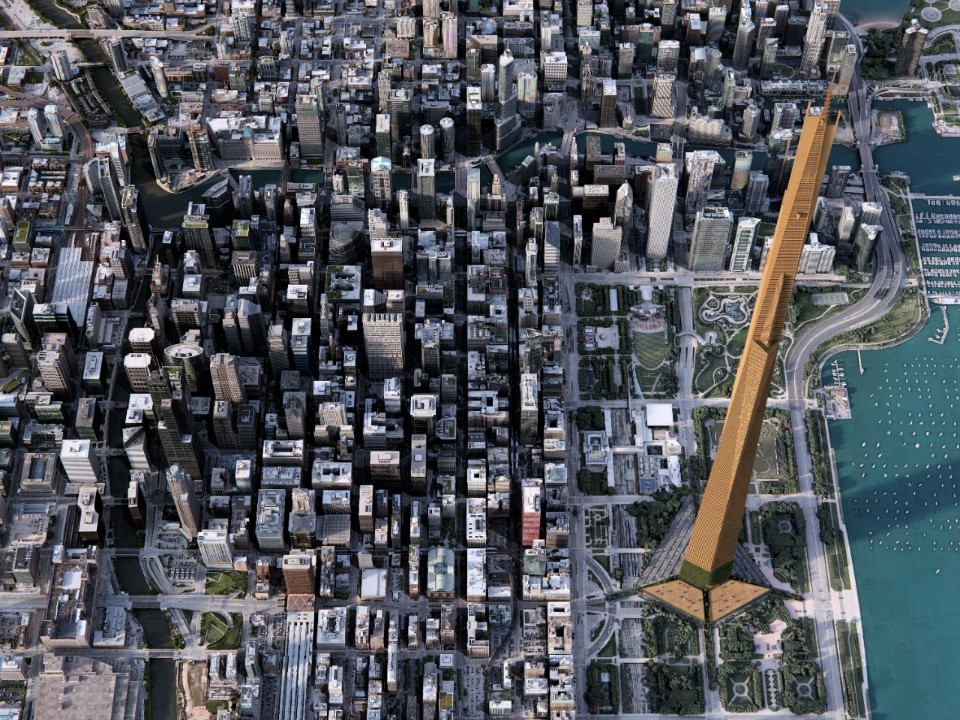

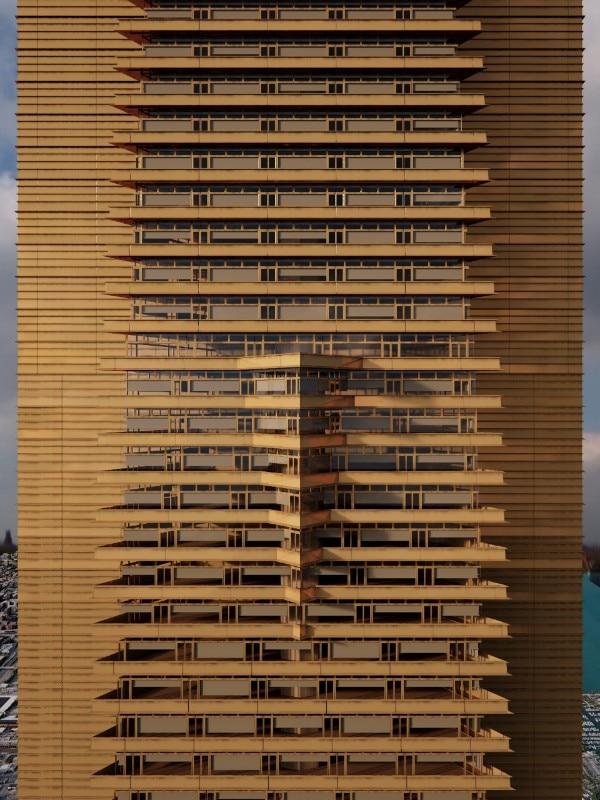

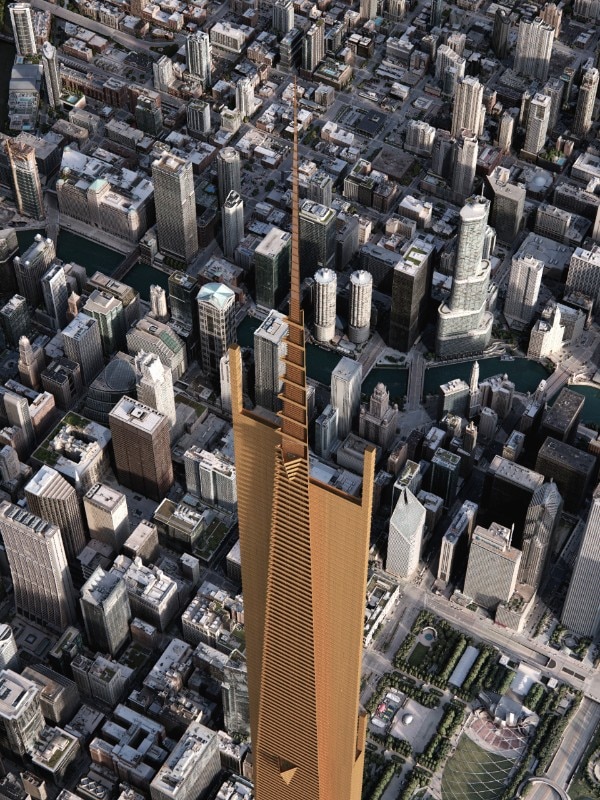

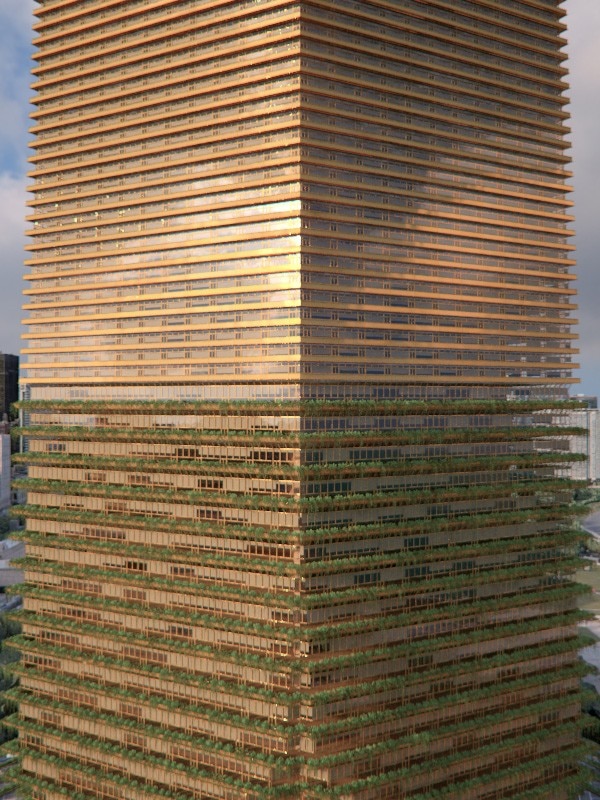

Wright’s unbuilt tower would dwarf the Burj Khalifa – and it was designed 70 years ago

View gallery

View gallery

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Frank Lloyd Wright, progetto per The Illinois, Chicago, 1956

Render di David Romero

© David Romero

Seventy years ago, the American architect presented The Illinois to the world: a tower more than two kilometres high and containing a veritable city with nuclear-powered elevators. Thanks to renderings by architect David Romero, we can now see what it would have looked like. Read more

Is sustainable architecture even possible?

Between submerged cities, high-altitude airports and inadequate regulations, the voices of Ghotmeh, Gang, Ma, Mandrup, BIG, Snøhetta and others reveal that sustainability is not a single concept. From the Holcim Awards emerges a landscape of differences, contradictions and new possibilities. Read more

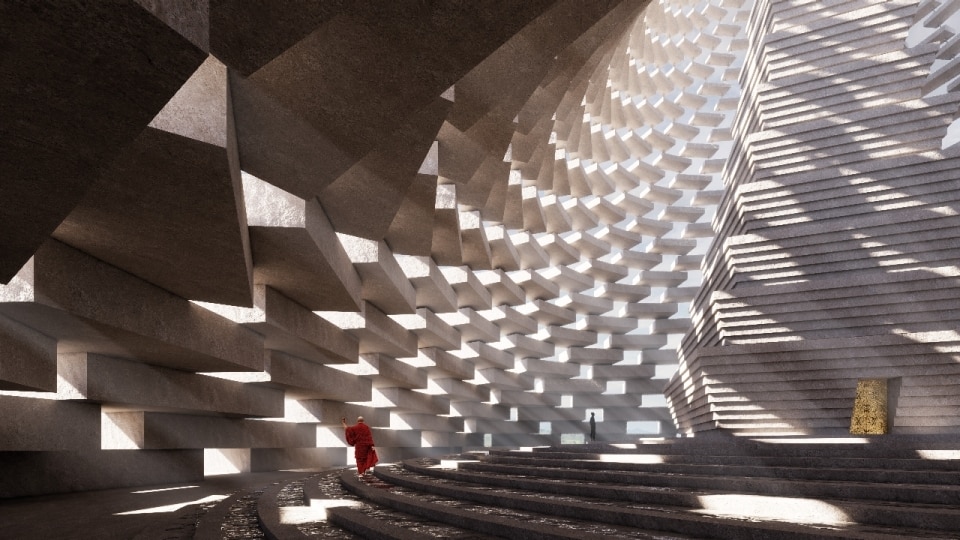

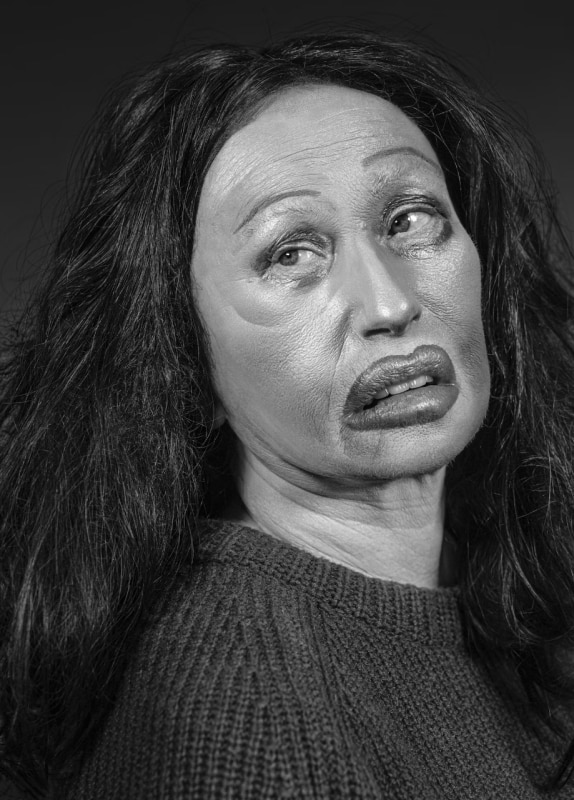

Designing the face in the age of computational imagery and Botox Bars

The face is no longer merely the site of identity, but a designed interface: between filters, “AI-inspired” surgery, parametric aesthetics and body modification, contemporary culture radically reformulates the relationship between image, technology and subjectivity. Read more

10 architectural gems of Milan you won’t find in the New York Times

View gallery

View gallery

1. Biblioteca Pinacoteca Accademia Ambrosiana, Francesco Maria Richini, Fabio Mangone and Giacomo Moraglia, 1609

Piazza Pio XI, 2, Milan, Italy

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

2. Grattacielo Pirelli (Pirelli Tower), Gio Ponti, Pier Luigi Nervi, Alberto Rosselli, Egidio Dell'Orto, Antonio Fornaroli, Giuseppe Valtolina, 1956-1960

Via Fabio Filzi, 22, Piazza Duca d'Aosta, 5-7A, Milan, Italy

Photo Stefano Bertolotti from Flickr

3. Citylife skyscrapers, Arata Isozaki, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Bjarke Ingels, 2015-ongoing

Piazza Tre Torri, Citylife, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

4. Piscina Guido Romano, Luigi Lorenzo Secchi, 1929

Via Giuseppe Zanoia, 2, Milan, Italy

Photo omnia_mutantur from Flickr

5. Monte Stella and Qt8, Piero Bottoni, 1947

Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Francesco Secchi (2022)

5.. Monte Stella and Qt8, Piero Bottoni, 1947

Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Francesco Secchi (2022)

6. Casa a tre cilindri (“Three-Cylinder” House), Angelo Mangiarotti and Bruno Morassutti, 1959-1962

Via Gavirate, 27, Milan, Italy

Photo Marco Menghi

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

8. Marchiondi Spagliardi Institute, Vittoriano Viganò, 1957

Via Noale 1, Milan, Italy

Photo Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

9. Church of San Giovanni in Bono, Arrigo Arrighetti, 1968

Via S. Paolino, 20, Milan, Italy

Photo Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

1. Biblioteca Pinacoteca Accademia Ambrosiana, Francesco Maria Richini, Fabio Mangone and Giacomo Moraglia, 1609

Piazza Pio XI, 2, Milan, Italy

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

2. Grattacielo Pirelli (Pirelli Tower), Gio Ponti, Pier Luigi Nervi, Alberto Rosselli, Egidio Dell'Orto, Antonio Fornaroli, Giuseppe Valtolina, 1956-1960

Via Fabio Filzi, 22, Piazza Duca d'Aosta, 5-7A, Milan, Italy

Photo Stefano Bertolotti from Flickr

3. Citylife skyscrapers, Arata Isozaki, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Bjarke Ingels, 2015-ongoing

Piazza Tre Torri, Citylife, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

4. Piscina Guido Romano, Luigi Lorenzo Secchi, 1929

Via Giuseppe Zanoia, 2, Milan, Italy

Photo omnia_mutantur from Flickr

5. Monte Stella and Qt8, Piero Bottoni, 1947

Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Francesco Secchi (2022)

5.. Monte Stella and Qt8, Piero Bottoni, 1947

Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Francesco Secchi (2022)

6. Casa a tre cilindri (“Three-Cylinder” House), Angelo Mangiarotti and Bruno Morassutti, 1959-1962

Via Gavirate, 27, Milan, Italy

Photo Marco Menghi

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

7. Monte Amiata Housing Complex, Gallaratese District, Carlo Aymonino and Aldo Rossi, 1967 -1974

Via Enrico Falck, 53, Municipio 8, Milan, Italy

Photo Carlo Fumarola

8. Marchiondi Spagliardi Institute, Vittoriano Viganò, 1957

Via Noale 1, Milan, Italy

Photo Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

9. Church of San Giovanni in Bono, Arrigo Arrighetti, 1968

Via S. Paolino, 20, Milan, Italy

Photo Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

Much has been made of America's leading newspaper's selection of buildings. We offer a different way of understanding Milan and why its architecture is so important. Read more

Designing the houses of After the Hunt: Luca Guadagnino’s architecture of desire

View gallery

View gallery

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

Luca Guadagnimo, After the Hunt, 2025, Production Design Stefano Baisi

©Amazon MGM Studios

In After the Hunt, a drama set in the rarefied world of Yale University, production designer Stefano Baisi transforms academic spaces into landscapes of emotion and control. Read more

The history of the Monobloc: the world’s best-selling chair

Everyone knows it, yet few remember its name. This is the story of an iconic chair – one that embodies democratic design. Read more

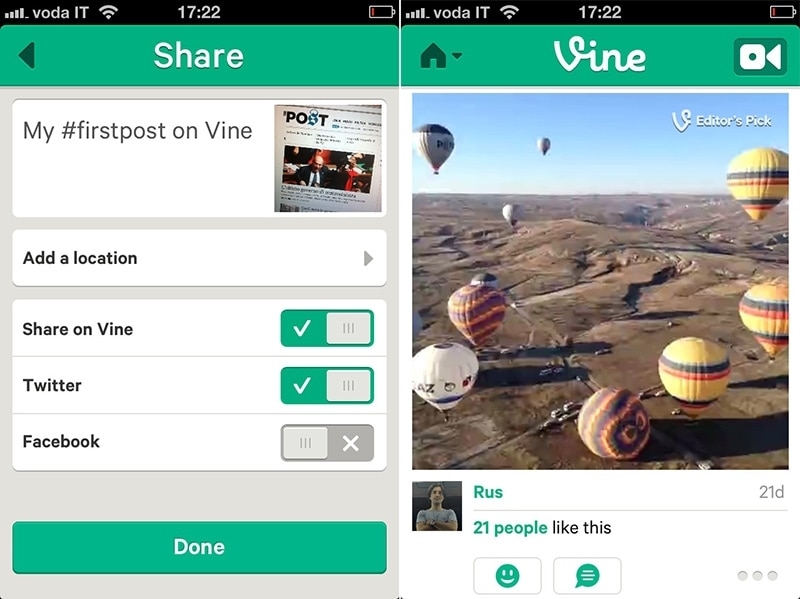

Before TikTok, there was Vine: why it invented the present

In six seconds, Vine crafted an entirely new visual grammar: loops, imperfect gestures and micro-architectures of meaning that return today with “diVine,” in the age of hyper-designed, algorithmic feeds. Read more

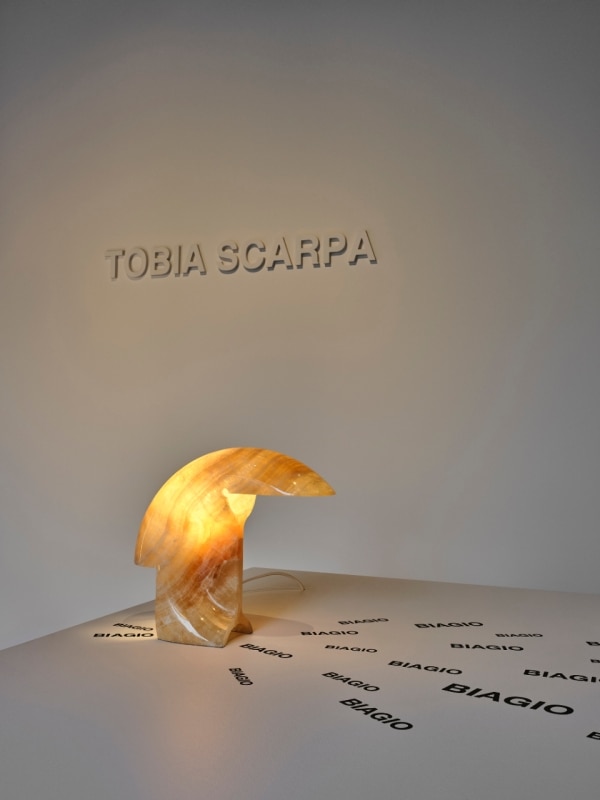

7 things Tobia Scarpa told us about design, architecture, and himself

View gallery

View gallery

Making stage of the Biagio lamp by Tobia Scarpa, frame from the making-of video by Andrea Caccia

Courtesy Flos

Making stage of the Biagio lamp by Tobia Scarpa, frame from the making-of video by Andrea Caccia

Courtesy Flos

Making stage of the Biagio lamp by Tobia Scarpa, frame from the making-of video by Andrea Caccia

Courtesy Flos

Making stage of the Biagio lamp by Tobia Scarpa, frame from the making-of video by Andrea Caccia

Courtesy Flos

Seven aphorisms and reflections by the Italian maestro, who is 90 years old, tell the story of a life that has crossed the history of design, always with lightness and depth. Read more

Elizabeth Diller, from High Line to the city of the future: “Architecture is so slow”

Diller Scofidio + Renfro is one of the firms that has had the greatest impact on the contemporary city’s image. We met with the American architect to discuss future visions and offer a critique of today’s architecture. Read more

Discovering Milan on foot: the architecture of Porta Venezia

Domus accompanies you on a walk to discover the area of Porta Venezia, tracing its evolution from the sixteenth-century Lazzaretto to a district dotted with emblematic rationalist architecture. Read more

Gae Aulenti changed 20th-century architecture, and these eight projects tell the story

A major book follows a retrospective exhibition to tell the story of “La Gae”, and through eight projects spanning urban planning to product design, Domus paints a portrait of the legendary architect who “did not want to be a specialist in anything”. Read more

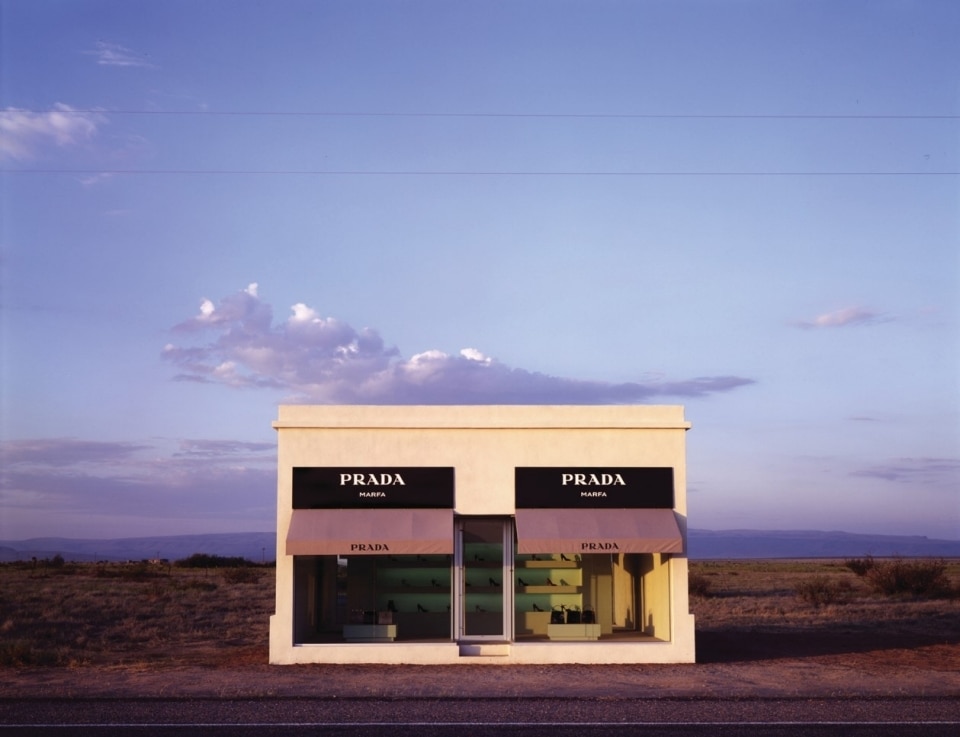

Elmgreen & Dragset, 20 years of Prada Marfa: “We still need magical places”

The two artists tell Domus how the famous public art installation in Texas continues to live on beyond their intentions, and how this has made it the popular and beloved work it is today. Read more

The art gallery that lives in a rental truck

View gallery

View gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

Vladimir Umanetz: Tina Turner Meets Kurt Gödel, U-Haul Gallery, Frieze London, 2025

Images Courtesy of U-Haul Gallery

“At $29.99/day, the U-Haul is undoubtedly the cheapest real estate in NYC”: James Sundquist and Jack Chase are the founders of The U-Haul Gallery, a project redefining how art is exhibited — now making its way to Frieze London. Read more

We create with AI and then feel guilty. Why does it happen?

Artificial intelligence is becoming part of our lives, but it also brings with it a psychological burden: “AI guilt.” Perhaps it’s time to stop apologizing. Read more

The Eames House reopens after the L.A. fires: “This house can teach architects a kind of humility”

Domus met with Eames Demetrios and Adrienne Luce of the Eames Foundation to rediscover how this “anti-iconic icon” of California Modern is also inspiring the future of a recovering city, in a way different from what you might expect. Read more

Without Zaha Hadid’s stadium in Tokyo, the Sympathy Tower would never have existed

A Tokyo suspended between reality and fiction, “neither empathetic nor courageous,” where a new tower reflects Zaha Hadid’s legacy. A visionary novel, winner of Japan’s most prestigious literary prize: author Rie Qudan tells Domus about it. Read more

Millennials don't inhabit homes anymore: they live in Instagram feeds

In a world where everything is performance, the home has become a personal stage. Every detail is curated, even in temporary spaces, while the dream of a forever home drifts further out of reach for most. Read more

What Oliviero Toscani has left us

Hated or beloved, venerated or misunderstood, Oliviero Toscani has changed photography and communication. Or he did not? We talked about him with those who worked with him, those who knew him, who were his friends and those who followed his steps. Read more

Opening image: Elmgreen & Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005, Photo Lizette Kabre. Courtesy of Art Production Fund and Ballroom Marfa