A home isn’t just a place to live; it’s where private life takes shape.

For millennials especially, it’s no longer just about occupying a space; it’s about showcasing it. A home has become less of a place to live in and more of a display. That’s because millennials don’t just live in houses anymore; they live in digital feeds and today’s spaces are designed also to be seen, shared, and – above all – framed.

On Instagram, TikTok, and other platforms, interior design has evolved into a visual language. It’s not just about taste or function anymore; it’s a way of portraying who you are through deliberate aesthetic choices. Colors, textures, materials, and layouts become part of a visual script that conveys values, lifestyle, and aspiration. Every corner is composed like a scene, a fragment of a carefully curated story meant for public consumption.

To live in the feed is to treat your home as an extension of your digital identity: a place that speaks in images, communicates without words, and tells others who you are (or who you wish you were). It’s a form of ongoing visual storytelling, shaping living spaces to fit a narrative you want to stage.

@thehavenly The biggest differences between a Gen Z home and a millennial home 🏡 #greenscreen #homedecor #interiordesign #genzvsmillenial #millennials ♬ Chopin Nocturne No. 2 Piano Mono - moshimo sound design

Think: Ikea bookshelves, anthropomorphic candles on coffee tables, boho rugs draped over parquet or porcelain tile, beige modular sofas bathed in golden-hour lighting.

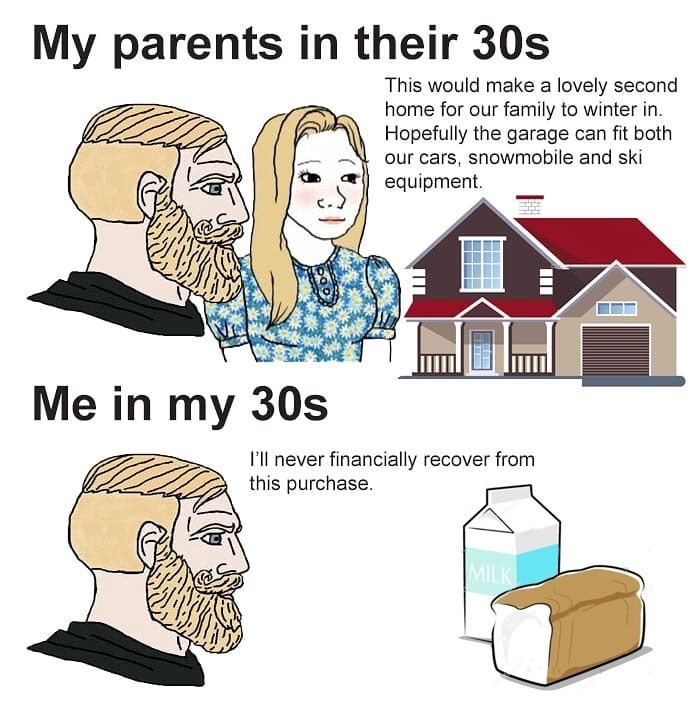

But here lies the generational contradiction: we build – whether in reality, imagination, or on Pinterest boards – an ideal home that’s warm yet minimalist, always perfectly tidy, that only a few can actually afford. The kind of space you'd see in a design magazine: open floor plans with microcement kitchen islands, resin bathrooms, terraces strung with fairy lights, and chunky wooden tables. So, the fantasy of “living well” is postponed to a distant future, until a greater financial stability arrives. In the meantime, we patch things up with a few carefully chosen items, a few compromises – because the real home is often a shared two-bedroom apartment, with a desk wedged between the bed and the wardrobe.

The millennial home exists in suspension between aspiration and frustration, between image and reality. A place shaped by generational voyeurism, where desire grows in direct proportion to its unattainability.

Social media smooths over this tension, turning scarcity and instability into a kind of curated minimalism. Millennials obsessively design spaces that are slow to materialize, pouring their aesthetic fixations into temporary homes. It’s a form of compensation for a structural impossibility, where meticulous attention to the ephemeral becomes the only available form of control.

The resulting aesthetic – even and especially in owned homes – is strikingly uniform: millennial gray dominates palettes and surfaces, from charcoal-toned sofas to pearl-gray walls. A neutral color that offends no one, fits everywhere. Gray has become the shade of those who chose mortgages over revolution, accepting 30-year payment plans as the cost of an increasingly elusive sense of stability.

This monochrome minimalism often bleeds into sad beige, a term popularized by comedian Hayley DeRoche in her satirical TikTok videos mocking the washed-out palettes of children’s clothing catalogs, worthy, as she put it, of “a Werner Herzog guide to sad childhoods.”

In the corners of these curated interiors, houseplants abound – monstera deliciosa, ficus lyrata, sansevieria – sprouting like a tamed jungle. They symbolize a nature that is both controlled and controllable, the only living presence permitted in homes designed more to be photographed than inhabited.

Millennial consumers are making choices from increasingly narrow catalogs of taste. The same beige sofas, gray tiles, and identical potted plants form a homogenized aesthetic, one that speaks less to personal expression and more to an anxious desire to belong.

A generation that favors open-plan layouts, studio apartments, micro-homes, and co-living arrangements – different ways of inhabiting space, all revolving around the same absence. Kitchens bleed into living rooms, corridors are eliminated, boundaries erased. These are solutions meant to “open up” space, yet more often they end up compressing the quality of everyday life.

The pandemic laid bare the limitations of this housing language. Remote work turned homes designed for a few waking hours into full-time offices. Even the least design-conscious among us were forced to reconsider their spaces, in search of more functional, adaptable, and – crucially – aesthetically pleasing solutions.

Somebody bought the Home Alone house, gave it the full 'Millennial Gray' treatment and I don't understand how this isn't a war crime.

byu/AshleyUncia inMillennials

In this ongoing fiction of daily life, the very idea of what it means to live is being redefined. Not rootedness or ownership, but fluidity and adaptation. Not the house of our parents – solid, stable, final – but a liquid space that exists as much online as off, ready to be disassembled and reassembled somewhere else. The millennial home exists in suspension between aspiration and frustration, between image and reality. A place shaped by generational voyeurism, where desire grows in direct proportion to its unattainability.