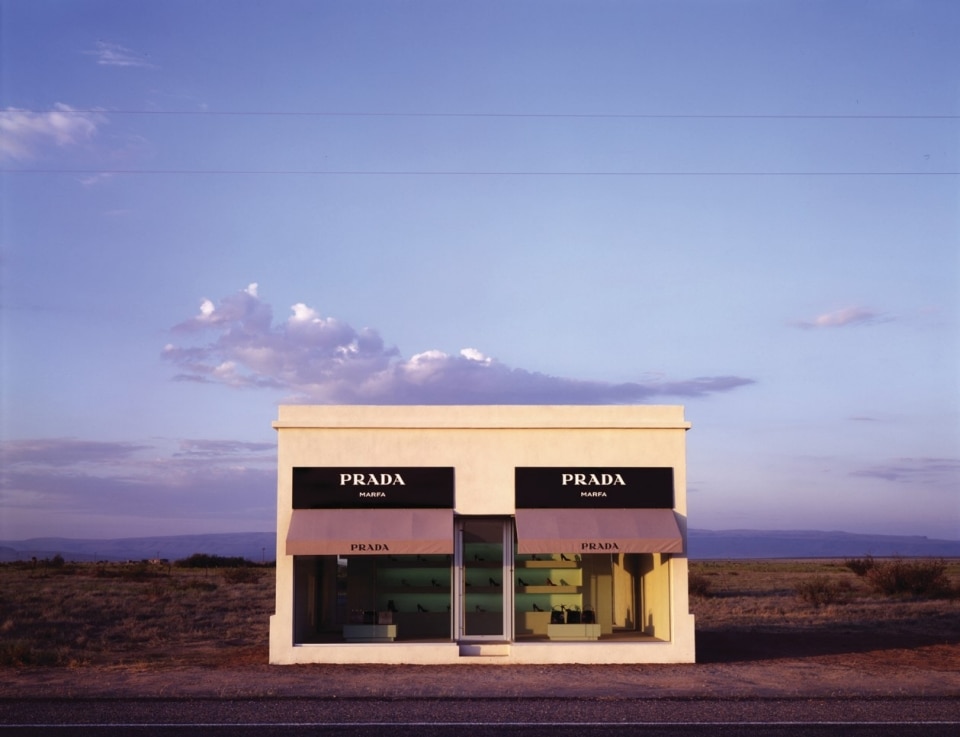

When Elmgreen & Dragset (E&D) began working on the Prada Marfa project, which marks its 20th anniversary this year, they asked themselves a question that had little to do with what the installation represents today, in 2025. For the duo, then focused on the processes of urban gentrification, the most compelling aspect of placing a hyperrealistic reconstruction of a Prada boutique along Highway 90, in the middle of the Texan desert, lay in the perceptual estrangement this “pop-architectural land art” sculpture would provoke in those who stumbled upon it unexpectedly, without anticipation. They wanted to explore the role of context in shaping our interpretation of the fashion system and, more radically, how a Prada store — a universal symbol of wealth and consumption — might appear if it embarked on a solitary journey of survival in the desert.

This obsession did not arise out of nowhere but stemmed from the increasingly pervasive spread of luxury boutiques, which in the early 2000s were gradually imposing themselves on culture and the urban fabric — something E&D experienced firsthand. The precursor to Prada Marfa was in fact a 2001 exhibition by the duo at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York, titled “Opening Soon/Powerless Structures”. Its central piece was a sign reading “Opening soon Prada” affixed to the gallery’s façade: an ironic commentary on an economy sacrificing artistic spaces to the rise of major fashion boutiques and chain stores. Many, caught in the conceptual trap of the work, even phoned the gallery director, distressed about its imminent closure and inquiring about details of the supposed new Prada store.

Prada Marfa was born from this intuition, embraced by the founders of the Art Production Fund (APF) and Ballroom Marfa, the two commissioning organizations that financed the construction of the permanent installation and located it in the Chihuahuan Desert, about 30 minutes from Marfa, the contemporary art mecca. As E&D explained to Domus in a long email conversation, it was not a random decision:

We came up with the idea of placing a luxury goods boutique in the middle of the desert due to our fascination with early land art projects. We have always loved these very remote art projects that are hard to reach, but nevertheless have such a presence

Elmgreen & Dragset (E&D)

Thanks to Donald Judd’s activity, which had transformed it into a laboratory of land art and minimalism, Marfa represented the ideal context for hosting a provocative work capable of intertwining reflections on the layered connections between art, capitalism, and the fashion industry. Not only had the commercial use of minimalism shaped the aesthetics and interior design of luxury boutiques in the early 2000s, but since the 1970s the town itself had become an urban hub at the center of global tourism, echoing the neoliberal dynamics that were reshaping major cities amid collective indifference.

From the outset, the work sought to play with these short circuits, acting as a small dystopian guide to disrupt our habitual perception and persuade us that the unthinkable was possible, that the seemingly obvious aspects of everyday life could contain contradictions and paradoxical traits. The goal was to intervene in the semantic link between content and context: altering one to draw attention to the other, in a continuous loop. For this reason, E&D decided to place a symbol of luxury in a barren setting, cut off from the flows of consumption, where the almost fetishistic nature of the brand could be exposed and dissolved into the desert landscape, in a slow process of “creative and generative decay,” as Dragset described it, caused by the action of natural elements.

Prada Marfa was inaugurated in 2005 with a “modest opening event, without much press attention”, and with the approval of Miuccia Prada, who, recognizing the expressive power of the project, allowed the artists to use the brand’s visual identity—from the color palette to the choice of carpeting—also donating original shoes and handbags from the Fall/Winter 2005 collection. The entire structure, designed together with architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, was built from adobe bricks, plaster, and biodegradable glass, with all the rigor of a true minimalist sculpture. Overall, its horizontal lines and the parallel arrangement of the display shelves were conceived to openly dialogue with the flat horizons of the desert landscape and Donald Judd’s modular installations, while the pistachio-green tones of the interiors subtly referenced Dan Flavin’s works exhibited at the nearby Chinati Foundation.

However, its initial vocation for slow obsolescence was short-lived. Just two days after the inauguration, the work was vandalized and looted: the façade of the building was defaced with graffiti, the windows were shot at, the door torn off, and the displayed objects stolen. The producers of the work and E&D themselves, while condemning the act, opted for a full restoration and reinstallation, believing that the destruction of the boutique had occurred before enough people could experience the sculpture in its original state.

Although the restoration was costly and complex — including the installation of an alarm system and bulletproof windows — the consequences of the vandalism proved decisive in attracting international media attention. In an unforeseen turn for its creators, Prada Marfa soon became embroiled in thorny legal disputes with the Texas Department of Transportation. Following a complaint regarding another public artwork commissioned nearby by Playboy Enterprises, Prada Marfa was taken to court and, eight years after its inauguration, risked closure when it was declared an “illegal advertisement” due to its use of the Prada logo. After a year of negotiations, it was granted museum status, with the building itself designated as the sole exhibition, and therefore allowed to remain.

Since then, and after having been vandalized countless times — including by artist Joe Magnano in 2014 — Prada Marfa has become a true pop icon and a world-renowned pilgrimage site, with a dedicated community committed to preserving it so that it remains safe, accessible, and faithful to the spirit of E&D’s original proposal, explains Ballroom Marfa. The work has therefore survived thanks to ongoing maintenance, which nonetheless makes clear that it was the gap between the original project and reality that gave it new life.

Prada Marfa twenty years later

Twenty years on, Prada Marfa is visited by thousands of people every year and is recognized as a cult destination — thanks in part to The Simpsons, Gossip Girl, and Beyoncé — that continues to raise crucial questions for the contemporary art system. However, since it was originally conceived as a reflection on the power of estrangement and decontextualization, can Prada Marfa still remain true to its original nature now that social media continuously reinsert it into the circuits of consumption, generating symbolic capital for the fashion house of which it is nothing more than a simulacra?

According to E&D, there can be no definitive answer to this question. “To us, an artwork’s meaning is never fixed, and it is only “finished” once it is experienced by those who encounter it. In that sense, the audience is not passive but an active participant, and the work lives on as more than an object, but as something animated through the interactions, stories, and reflections it generates”. As they told Domus, every artistic intervention — especially when placed in public space — inevitably embarks on unpredictable paths, embracing multiple reactions and relationships.

We sometimes describe Prada Marfa as a child we’ve raised: at some point, the child grows up and leaves home and begins their own life, shaped by others, outside of our control. That’s how we see the work today, and therefore it will for sure evolve over the coming decades beyond our initial intentions. Maybe it will even outlive us.

Elmgreen & Dragset (E&D)

In a broader sense, it is not wrong to claim that the fate of Prada Marfa is intertwined with the transformation of art reception in the digital age. Its remote isolation has not cut it off from the flow of events, nor from the evolution of contemporary culture. On the contrary, the circulation of images of the work on the internet and social media has catapulted it into a matryoshka of signs, simulacra, and simulations — to borrow Baudrillard’s words — exponentially amplifying its symbolic ambivalence. “People project their own stories onto it. For some, it’s a backdrop for a travel photo or a celebration; for others, it’s a critique of consumer culture. Of course, it can be seen as a reflection on the overlaps and exchanges between art and fashion, not least the crossover interest in minimalism, but that’s only one of the many ways it can be interpreted”.

On one hand, the project was founded on the idea of changing our way of looking at a luxury boutique by placing it in an unusual relationship with the desert landscape; on the other, the gaze it has received over the years has often remained the same: the public seems to be fascinated and intrigued by Prada Marfa precisely because of its association with Prada and the set of real values tied to it, all the more so because they are placed in such an unreal atmosphere. “We think part of its popularity comes from the contradiction at its core: It looks like a fashion boutique, but it’s permanently closed, sitting in this desolate location like some sort of mirage”.

Yet, even this contradiction only deepens the sense of incredulity before a work that has managed to remain identical to itself despite the world around it having changed, suspended in time like a mirage, fixed in the immutability of uniform monotony. Prada Marfa continues — and will continue — to exist in the desolation of the desert, still and protected, resisting both silence and invisibility. A distant presence, yet in perpetual intimacy with the projections and stories of all those who have experienced it: an almost comic gesture that ultimately works as a reassuring spell, because, as E&D remind us, “in a period of global gloom, we need magical places”.

Opening image: James Evans, Prada Marfa, 2005, digital photograph.