Stumbling upon Scarpa’s Gavina store in the heart of Bologna is a disorienting moment – like a sudden flash of inspiration that throws us back into a time of intensity, precision, and architectural brilliance that helped shape Italian design.

We revisited this experience to celebrate the building’s recent restoration, made possible by its current owner, Claudia Canè Draghetti, and architect Elisabetta Bertozzi, but also thanks to the new tenants, the team behind Vintage 55, who have preserved the spirit of the space right down to keeping the original Gavina sign visible on the façade.

To understand the origins of Scarpa’s project, we need to rewind to the late 1950s on Via Altabella, in Bologna’s historic center. Picture a central, middle-class street just steps from Piazza Maggiore, where a man – equally central to its cultural fabric and beyond – is strolling: Dino Gavina.

Gavina (1922–2007) was a multifaceted and complex figure, a designer and entrepreneur who played a pivotal role in shaping Italy’s industrial furniture production in the 20th century. He helped build the legacy and the collections of now-iconic brands like Gavina, Simon, Flos, and Cassina.

A true art connoisseur and master talent scout, Gavina – and his entrepreneurial genius – is at the heart of this story as the commissioner of a store in Bologna that would become a cultural and commercial hub for design, showcasing pieces that were rapidly becoming icons, many of which still populate our homes today.

Scarpa’s unparalleled work on the Olivetti showroom in Venice’s Piazza San Marco – completed in 1958 – was still fresh when, in 1961, Gavina invited Scarpa to reimagine an entire storefront on Via Altabella. The request was for no ordinary commercial space, but for a state of the arts exhibition center: he gave Scarpa carte blanche to create an authentic “temple of furniture.”

By that time, Scarpa was already an acclaimed architect and saw in Gavina a kindred spirit, someone who would give him the freedom to experiment and leave a lasting mark. A Venetian by birth, with deep roots in Vicenza, Verona, and Venice – where he studied and collaborated with some of the best craftsmen of the time – Scarpa ventured into the culturally and architecturally different terrain of Bologna.

Even today, standing before the store, one can sense the boldness with which Scarpa approached the project. He inserted himself into the Bolognese urban fabric with both force and finesse, tempered only by his masterful attention to materials and detail.

The façade is a striking gray concrete, etched with horizontal lines that contrast sharply with Bologna’s typically warm earthy tones. The surface is interrupted only by two monumental openings: one a single circle, the other a pair of circles joined together, evoking the math symbol for infinity.

Scarpa’s signature sense of proportion is evident right away: from the outside, the store stretches lengthwise along the street, but he limits the glass openings to just two, focusing the attention of passersby and drawing them inward like a visual magnet.

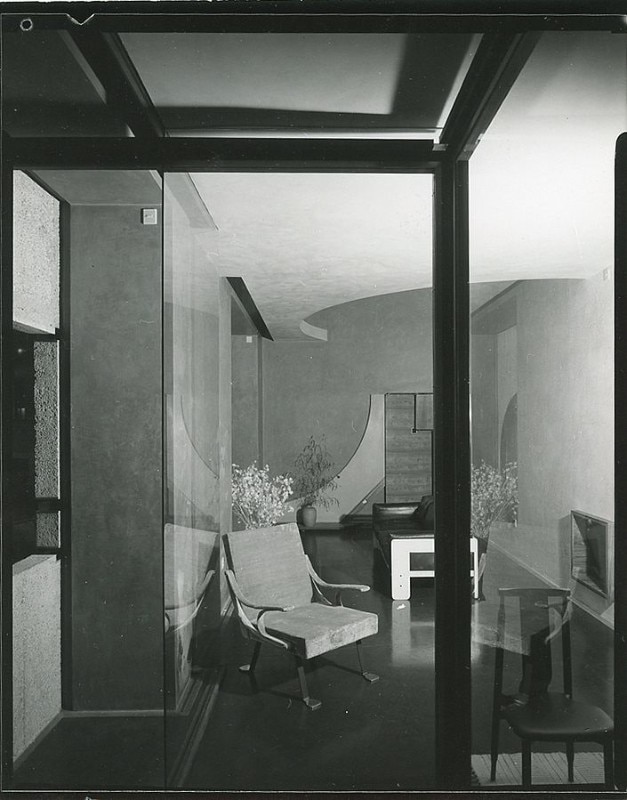

Scarpa’s genius for blending interior and exterior is already on full display. As you search for the actual entrance, you find yourself in home-like threshold space: an inner loggia nestled between the two circular windows. This vestibule recalls the secluded landing areas used by private boats in Venice. A finely wrought metal gate marks – both symbolically and literally – the transition from outside to in, placing us in a liminal space before crossing the true threshold of the store. Once inside, the store becomes a sensory experience, where Scarpa invites us to observe the details and encourages us to touch the wood, metal, and each bearing masterful finishes and superficial treatments.

Upon entering, we find ourselves in an exhibition area bathed in natural light from the large windows on the façade and softly illuminated by slivers of light filtering through cracks and angled openings in the ceiling.

Though the store runs parallel to the street, its sense of verticality is striking. Columns designed to be restlessly upright, as if impatient, are clad in wood and marked with inlaid metal. The walls, punctuated with other kinds of marks, seem to segment the space while urging us to move through it and explore its hidden details, like the small fountain tucked into the most secluded, intimate corner decorated with golden stone mosaics. Every proportion within the store evokes the domestic scale of a living space, but one elevated and devoted to the art of display.

Color plays a key role in this space, perhaps a nod to Scarpa’s early years at the Academy in Vicenza and his interest in painting. Cobalt blue walls, raw concrete, natural wood, black enamel, and flashes of orange are layered with subtle variations of beige and gray. What clearly emerges is Scarpa’s belief in the fundamental relationship between architect and craftsman, a collaborative, four-handed process in which the project evolves during construction itself, shaped by the shifting nature of materials and building solutions.

As we leave, we glance once more at the shop windows. This time, they seem to echo the very elements Scarpa and Gavina would later incorporate into the Doge table, designed just a few years after the store. We emerge slightly disoriented, as if stepping out of another time. A time when care, precision, and obsessive attention to detail could transform architecture into an experience, not just a physical space.