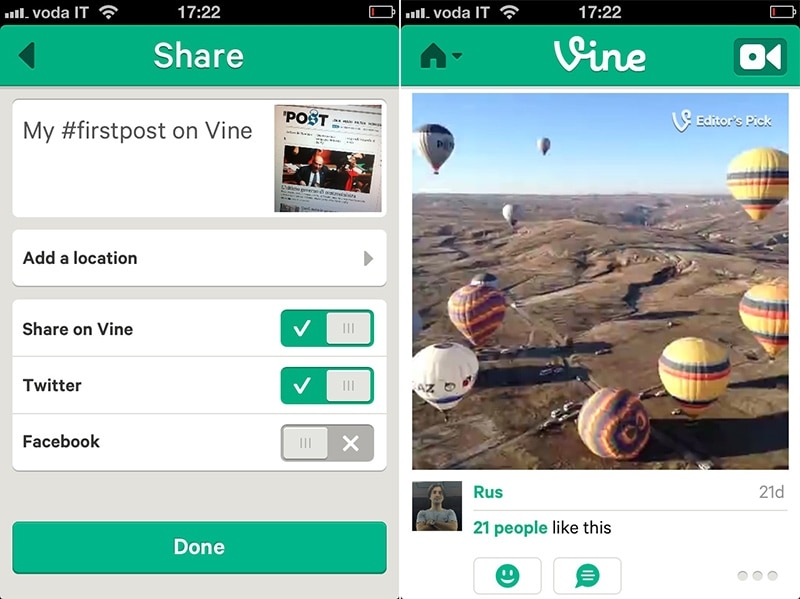

“Thank you for all the inspiration, laughs, and loops.” That’s what greets you today on Vine.co, frozen in its archival state since 2017.

When Vine launched in 2013, it felt more like a graphic toy than a platform: six seconds, cut into a loop, a format so compressed it became its own micro-space, with its own rules and its own language. A hyper-brief, hyper-repetitive environment built for quick, often nonsensical entertainment. Ten years after its disappearance, thanks to a recovered backup that restored its archive, navigating Vine is not just a return to a pre-social, more naïve and lo-fi moment — it’s an encounter with a visual habitat that is fragile and, paradoxically, more artificial than the feeds that dominate our screens today.

The six-second limit wasn’t just a technical constraint; it was a design device. Vine’s entire ecosystem emerged from narrative compression. That microscopic span forced the construction of gestures and gags that self-signified within the loop, generating an abstract, decontextualised humour built on errors, accelerations and collapses of meaning. Absurdity wasn’t a glitch — it was structural. Content worked only because it existed inside that form, that temporal capsule that made it possible.

And those six seconds proved powerful enough to capture unexpected and dramatic events as well, such as the footage recorded by a Turkish journalist moments after an attack outside the U.S. embassy in Ankara in 2013.

Vine wasn’t merely a precursor; it was a dress rehearsal for today’s compulsive scroll, a prototype of the visual ecosystem where attention is measured in seconds and meaning emerges through shocks, hints, micro-loops.

In today’s climate of cyclical returns, the name Vine reappears as “diVine,” reopening the conversation around the aesthetics of ultra-short videos. “DiVine” attempts to recreate that visual habitat — naïve and artificial at once — seeking survival without AI, relying solely on real gestures. It’s almost a curatorial stance, a poetic declaration more than a technical feature: an attempt to reclaim the materiality of the imperfect frame, the spontaneity of the gesture, the micro-incident that only a human context can produce. If Vine, in the 2010s, anticipated a future velocity, diVine seems determined to carve out a minimum space where something genuinely happens, before being normalised or replicated endlessly by generative models.

Revisiting Vine’s archive through this new return means recognising the cultural value of its fragility. Vine did not leave a linear legacy, but a way of perceiving time and the rhythm of images — a visual lexicon that subsequent platforms absorbed and transformed. diVine tries to reopen that grammar, resisting technological acceleration almost as a conceptual restoration. For those who did not experience Vine firsthand, this comeback is not mere nostalgia but an opportunity to observe how a micro-visual environment is constructed: a human ecosystem, brief and imperfect, whose apparent lightness concealed one of the earliest attempts to design an autonomous digital imaginary.

That hyper-compressed grammar anticipated today’s feed velocity, yet in a form surprisingly distant from the hyper-designed platforms that followed. Vine was naïve, almost handmade: the nonsense of “It’s an avocado… thanks” or the skateboarder yelling “Welcome to Chili’s” didn’t build stories; they built gestures. These videos were self-contained micro-spaces, unable to live outside their extinct format. This is why Vine’s aesthetic feels closer to the field of design than entertainment: an environment where time folded onto itself and repetition became material.

Some iconic Vines — from “Road work ahead? Uh, yeah, I sure hope it does” to the “What are those!” clip — endure less for the punchline than for the formal spark of the loop: a repetition that turned absurdity into a small pop mantra. Rewatched today, many fragments appear more choreographed than they once seemed: tiny performances of estrangement that only functioned within that temporal box, unable to survive the expanded forms of Reels and TikToks.

diVine tries to reopen that grammar, resisting technological acceleration almost as a conceptual restoration.

Vine wasn’t merely a precursor; it was a dress rehearsal for today’s compulsive scroll, a prototype of the visual ecosystem where attention is measured in seconds and meaning emerges through shocks, hints, micro-loops.

What is striking, rereading them now, is how Vine resembled a designed environment: a micro-architecture of the ephemeral in which every element — anticipation, abrupt interruption, hypnotic repetition — built a rhythm closer to gesture than content. Like a temporary pavilion: minimal, fragile, ready to disappear, yet capable of defining a formal tendency. Even its lo-fi aesthetic — blurry frames, wrong lighting — now reads like a manifesto of pre-algorithmic authenticity, a form of digital craftsmanship born before the polished design of contemporary feeds reclaimed the chaos.

Today Vine appears as an architecture with no inhabitants, a shell preserving an aesthetic that cannot migrate elsewhere. It cannot work on TikTok or other digital surfaces: its humour, its energy, its very reason for being exist only in that semi-extinct format betting on its own rebirth.