by Matteo Pirola

photographs by Francesco Secchi

The slice of the city that Domus invites you to explore up close—measuring human bodies against urban ones—is the area just outside Milan’s Eastern Gate, along that endless road that runs straight to Venice.

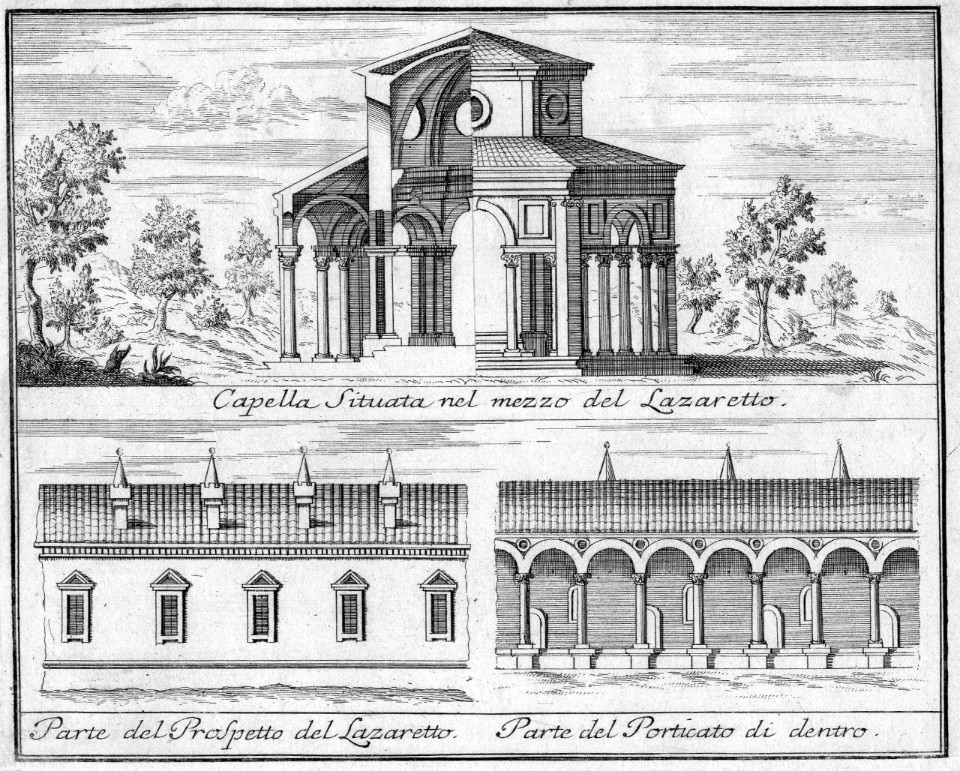

This area, just beyond the gate, is historically the site where Milan’s Lazzaretto was built—a monumental structure erected at the end of the 1400s to house and isolate those infected by the plagues that afflicted medieval cities. At the time, before the building existed, this was all open countryside.

1. First stop: a journey back in time through the “quadrilateral of death”

Long before the famed “fashion quadrilateral” (quadrilatero della moda) (a little further away), this was a “quadrilateral of death” —but one where you could survive, or, like “Lazarus”, be resurrected. That’s why it’s called a lazzaretto and not a leper colony or something else, and why it is ultimately designed as a great place of waiting, almost like a holiday resort arranged in rows.

It had a very regular shape, about 400 metres on each side, which today corresponds exactly to Via Lazzaretto (aptly named), Via San Gregorio, Corso Buenos Aires and Viale Vittorio Veneto.

Inside the inhabited wall, there was a long, continuous colonnade overlooking a vast lawn (about the size of 20 football fields) in the center of which stood a central octagonal shrine, open on all sides, which, in a panoptic arrangement, allowed all the sick to see the religious rites from their cells.

After more than a century of hospital activity, and following the great plague of 1630—also recounted by Manzoni in The Betrothed—and thanks to modern medicine which found new remedies to many diseases, the gigantic structure slowly lost its use and began an irreversible period of repurposing, decay and then abandonment.

Until 1860, when the enclosure was split in half by a railway viaduct leading to what was then the new central station of Milan. Once this breach was opened, the medieval parts were gradually demolished according to an investment and reconstruction plan that, by the end of the 19th century, transformed that entire open area into one of the first neighbourhoods for the city’s new industrial bourgeoisie.

Today, almost nothing remains of that building except its story. In addition to walking the four streets that precisely trace what was once its boundary, and the internal streets all named after figures involved in the Lazzaretto and plague care, one can also, exceptionally, come across two original parts of what was once this majestic and industrious structure.

2. The church of the Lazzaretto, which dates back to the late 1500s, still exists

View gallery

View gallery

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Chiesa di San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani 1

Foto Francesco Secchi

Pellegrino Tibaldi, Church of San Carlo al Lazzaretto, 1576-92, Largo Fra Paolo Bellintani

The central open chapel, designed by Pellegrino Tibaldi on the site of a first simple altar, after various vicissitudes (including its transformation at the end of the 1700s by Piermarini into the Temple of the Homeland of the new Cisalpine Republic), was renovated at the end of the 1800s, enclosed on the sides, and reconsecrated as a church dedicated to its original patron, Saint Charles Borromeo. In addition to the stylistic elements typical of the era and a special acoustic due to the configuration of the dome (under which many concerts are held), its interior proudly displays the Borromeo family motto, Humilitas, in several places—an early masterpiece of graphic design, where text and image have achieved a perfect and rational balance for centuries.

Other parts of the original building are scattered throughout various sites—sometimes integrated and transfigured into historic Milanese buildings as noble recovered elements, other times as more recognisable and declared fragments. For instance, at Villa Bagatti Valsecchi in Varedo, the family—deeply engaged in the arts and architecture of the time—transferred and reconstructed some sections of the inner portico and the so-called Minor Gate, within the context of the period’s fascination with gardens filled with wonders from the past.

3. Discover the remains of the Lazzaretto, not far away

Lazzaro Palazzi, Lazzaretto, 1489-1509, via San Gregorio 5

A full section of the original building block—six small cells with an internal portico and external moat—has been preserved as one of Milan’s first historical monuments. This was thanks to Luca Beltrami, who published its history and some redrawn plans in 1882, and who made a name for himself in the city’s history with numerous other restoration and reconstruction projects.

Since 1974, these small rooms have housed an Orthodox Church and are part of a school complex built at the end of the 19th century as an educational facility for what was then a new bourgeois district.

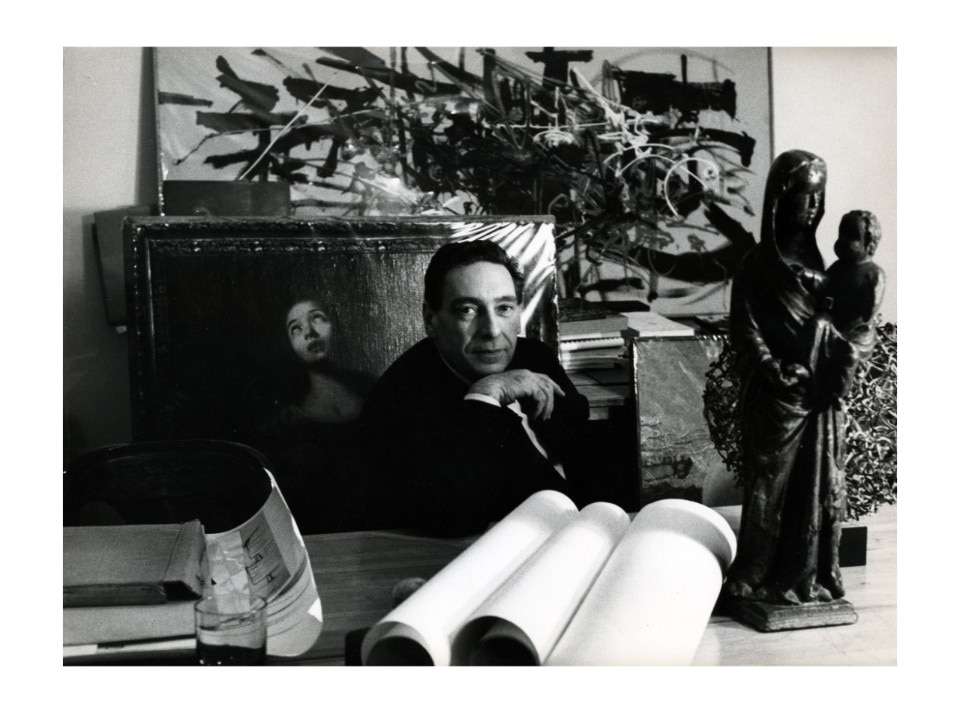

4. A building by Vico Magistretti stands right next to the Lazzaretto

Vico Magistretti, Multifunctional building, 1957-59, Via San Gregorio

On the lot adjacent to this very architectural relic, a young Vico Magistretti undertook one of his first urban buildings (1957–59), a multifunctional composition housing flats, offices along the street edge, and a cinema set further back. The Lazzaretto was an explicit reference in his chromatic and expressive choices, in an early 'modern reinterpretation of tradition'—a direction that would find more significant expression in the city, especially in the 1960s.

View gallery

View gallery

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

Vico Magistretti, Edificio polifunzionale, 1957-59, via San Gregorio 3

Foto Francesco Secchi

On the façade, made of reddish gravel prefabricated panels and rhythmically marked by 45° angled reinforced concrete pillars like buttresses, clear references to the past can be seen. Between slender, orderly Milanese-style French windows, there are service openings that animate the façade like medieval slits. On the free northern side, which overlooks the Lazzaretto, Magistretti placed the living areas, which can open directly with modest bow-window-style balconies.

5. The underground train station bears the signature of Mangiarotti

The current district thus takes the walker back in time, from the years of its modern birth in the 1880s, to its transformation in the 1930s following the demolition of the railway viaduct to open the new and final Central Station of Milan. But it is also dotted with architecture that vividly expresses the journey Milanese modern architecture took in the post-war years, accompanying the city's progressive development into its contemporary form.

Descending underground—often the realm of hidden yet equally fascinating places—one finds the iconic stations of Line 1, inaugurated in 1964 and designed by Franco Albini and Franca Helg with Bob Noorda. But one also finds, though less well known, the stations of the Passante railway, designed by Angelo Mangiarotti and inaugurated in 1997.

Mangiarotti, who had long served as a consultant for the Milan Passante project, designed the peripheral stations of Rogoredo and Certosa in the 1980s. He completed his work with two more central stations: Porta Venezia and Piazza Repubblica. The typological theme of the gallery—the long vaulted excavation created in the belly of the city to house the stations—was redefined by Mangiarotti to clearly reveal the structural logic through expressive form

Angelo Mangiarotti, Passante Ferroviario Stations - Porta Venezia and Piazza Repubblica, 1997

At Porta Venezia station, a wide mezzanine is suspended by angled steel cables attached to innovative “cellular arches” that support the structure and define its length, punctuated by stairways leading to the train platform below. This elevated mezzanine, detached laterally from the vault, exposes the structural system used for excavation and visually connects the train boarding area with the entrance, circulation and distribution spaces of the station.

At Repubblica, on the other hand—since it lies beneath a 'square' and seeks to emphasise the action of entering and exiting a vast urban basin open to the sky—the mezzanine is reduced, segmented and distributed over two levels, linked by a complex stair system. In this high, intricate and subterranean space—nonetheless illuminated by zenithal natural light perceived by passengers entering or exiting the station—an exposed reinforced concrete structure features massive columns branching at the top to support a ribbed ceiling. The platform level, clad in yellow to mark its intersection with Metro Line 3 (built at the same time), is surmounted by a broad continuous vault with distinctive large concave studs designed to absorb the sound of passing trains.

6. Back above ground: discover the 1930s of Viale Tunisia

The north-south axis of Viale Tunisia—freed first from the tracks of the 19th-century railway viaduct (later replaced by the underground Passante)—is today one of the most coherent examples of 20th-century expression in Milan, with buildings dating to the 1930s.

On this avenue, once named after Queen Elena, several works stand out by a seemingly minor, little-known and underappreciated architect who nonetheless built prolifically during those years: Giuseppe Martinenghi. Almost anonymous, but with a recognisable style, he constructed nearly 300 buildings, including at least six along this avenue and another twelve in the immediate surroundings.

Two buildings from this period are especially notable: the Roberto Cozzi swimming pool and the apartment block by Asnago and Vender.

7. Don’t miss the work by Maurizio Cattelan at Piscina Cozzi, a rationalist jewel

Luigi Secchi, Roberto Cozzi Swimming Pool, 1933-35, Viale Tunisia 35

The most monumental and striking building along this stretch is undoubtedly the sports complex housing the swimming pool named after Roberto Cozzi. Designed by Luigi Secchi in the mid-1930s for the Fascist-era “Littoriali dello Sport”, Secchi was a municipal architect with expertise in public works such as open-air baths and covered markets around the city. At the time of construction, this was Italy’s first indoor heated swimming pool and among the largest in Europe.

Its reinforced concrete structure, marble finishes and original grandstands—seating 4,000 spectators—make it a major cultural landmark not only in sports but also in architecture and art. Beneath the great vaulted roof, since 2021, there has been a permanent installation titled “Be Water” by Maurizio Cattelan and Pier Paolo Ferrari, the duo behind Toiletpaper. The work is a tribute to the history of this place and to its many daily users. The entire facility is now awaiting a major renovation, which will reopen extraordinary currently unused areas such as the entrance hall—once home to a café—and the underground public showers that served the neighbourhood.

8. Opposite the pool stands a very interesting modern residential building

Asnago and Vender, Residential and office building, 1935, Viale Tunisia 50

By the cult architectural duo Asnago and Vender—who made early architectural modernism their declared manifesto—the building at 50 Viale Tunisia is a compact, travertine-clad structure combining residences and offices. Their works are often abstract compositions, revealing unmistakable details to those who dedicate more than a passing glance. This building reinterprets the traditional Milanese ring-house model, placing balconies at the centre of attention, projecting various types outward from the façade and giving each apartment generous opportunities for outdoor living and views.

View gallery

View gallery

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

Asnago e Vender, Condominio abitazioni e uffici, 1935, viale Tunisia 50

Foto Francesco Secchi

9. In the same area: visit the hotel-residence by Luigi Moretti, architect of the Watergate

In the neighbouring blocks of this historic area, numerous other projects have helped make Milan a reference city for modern architecture in the post-war era.

Luigi Moretti, House-Hotel for temporary residences - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, Via Zarotto 8

Among them is a building by the great Roman architect Luigi Moretti—famous for the Watergate complex—located at Via Zarotto 8. Forced to stay in Milan due to political complications linked to the Fascist regime (he was imprisoned for his affiliations), Moretti met a construction entrepreneur in San Vittore prison, with whom he founded Cofimprese to design and build new projects in Milan. This is one of three completed buildings from a wider system of 22 temporary residential hotels built in the city immediately after the war to meet urgent housing needs during reconstruction.

View gallery

View gallery

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Luigi Moretti, Casa-Albergo per residenze temporanee - Hotel Ibis, 1947-53, via Zarotto 8

Foto Francesco Secchi

Each development consists of a complex of volumes usually forming an internal courtyard: taller buildings for rooms, lower ones for shared services, connected via a central distribution atrium. The architectural language is abstract, though enriched with details—cornices, bases, projections—reflecting Moretti’s deep knowledge of history and art. The building is volumetrically compact yet articulated, perfectly suited to the kind of modern and original development Milan was experiencing. Known in the 1960s as the American Hotel, it is now the Ibis Hotel. Fortunately, the original structure has been preserved and is honoured with a small permanent exhibition in the public foyer.

Our walk continues in the Repubblica district, along Viale Vittor Pisani, where the so-called 'Milanese downtown' took shape.

(to be continued...)

Opening image: Roberto Cozzi public swimming pool. Photo Francesco Secchi