by Carla Rizzo

“Being so nomadic from one place to another, from one job to another” is the hallmark of the life of Gaetana Emilia Aulenti, “La Gae”: she made it her banner, proudly choosing “not to want to be a specialist in anything,” and devoted herself to architecture, theatre, and design with the same stubborn determination that she considered inherent, among other things, to the “female condition.” From the province of Udine, where she was born in 1927, she moved to Biella, then to Florence, and finally to Milan, where she graduated from the Politecnico in 1953, before bringing her projects to the entire world. With the same resolve, she also traversed ten years (1955–1965) at Casabella-Continuità with Ernesto Nathan Rogers, the only woman among his male disciples, enjoying a privileged vantage point on the architectural, urban, and above all critical scene of Italy at the time.

This is how a multifaceted and essential figure took shape, celebrated by the Triennale di Milano with the major retrospective "Gae Aulenti" (1927–2012), and now with the volume La Gae. The Life and Times of Gae Aulenti (Electa, 2025), edited by Giovanni Agosti with the Gae Aulenti Archive. And it is in this same way that Domus also seeks to celebrate her, in the complex multiplicity of her work, spanning large urban plans, product design, stage sets, and the domestic dimension.

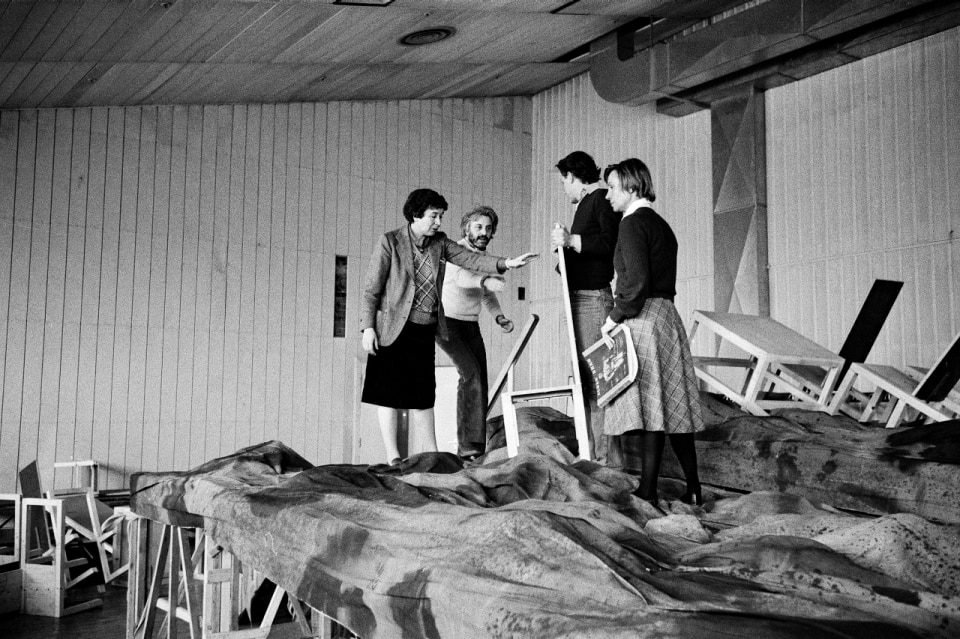

The starting point: the XIII Triennale di Milano, dedicated to “leisure.” In the Italian section, Aulenti and Carlo Aymonino were tasked with setting up the room immediately following The Time of Holidays: after the claustrophobic tunnel of cars jammed between rubber dinghies on their roofs and suffocating piles of luggage, The Arrival at the Sea offered visitors a powerful taste of that sense of expansion that always accompanies summer holidays, the physical and mental distance from the labours of daily life.

The disorienting multiplication of Picasso’s Two Women Running on the Beach bursts forth as the most childlike manifestation of joy, a liberating gesture in the act of Arrival, the run towards the long-awaited destination: the sea. A figurative choice in which the resemanticization of Picasso’s 1922 painting is graceful and never disruptive; rather, the two bathers are welcomed into new and unexpected settings.

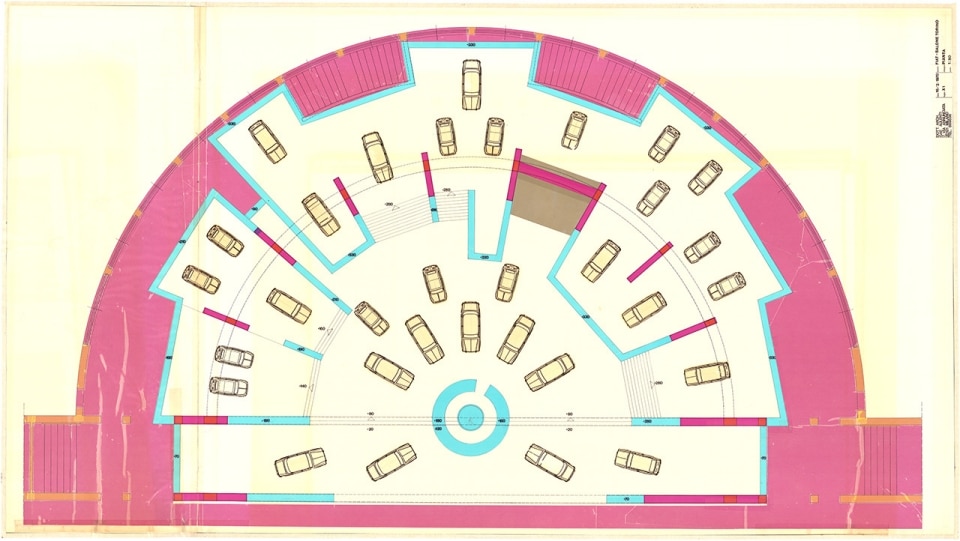

A very different display was that of the Fiat showrooms (1969–70) in Turin, Rome, Zurich, Vienna, and Brussels: they became an experimental manual for the furnishing of Fiat dealerships worldwide, and also the beginning of a collaboration with the Agnelli family, which helped raise Gae’s international prestige, though not without criticism for her way—once again a deliberate choice—of being “inside” rather than necessarily “against” (to use Pier Vittorio Aureli’s words) the bourgeois capitalist system of which Fiat was certainly the highest symbol.

I don't want to be a specialist in something. I think this is a feminine condition, this choice that makes you prefer things deeper down instead of on the surface, that makes you prefer, for example, knowledge to power.

Gae Aulenti

The showrooms carried an innovative idea: spaces that actively participated in the staging of the product and engaged the visitor in a dynamic experience, truer to the object on display—the automobile. Gallery-like pathways, sloping platforms, and lighting systems blurred exhibition and street, generating, also at the Triennale, a sense of disorientation between interior and exterior, in a complex and ambiguous space that took centre stage.

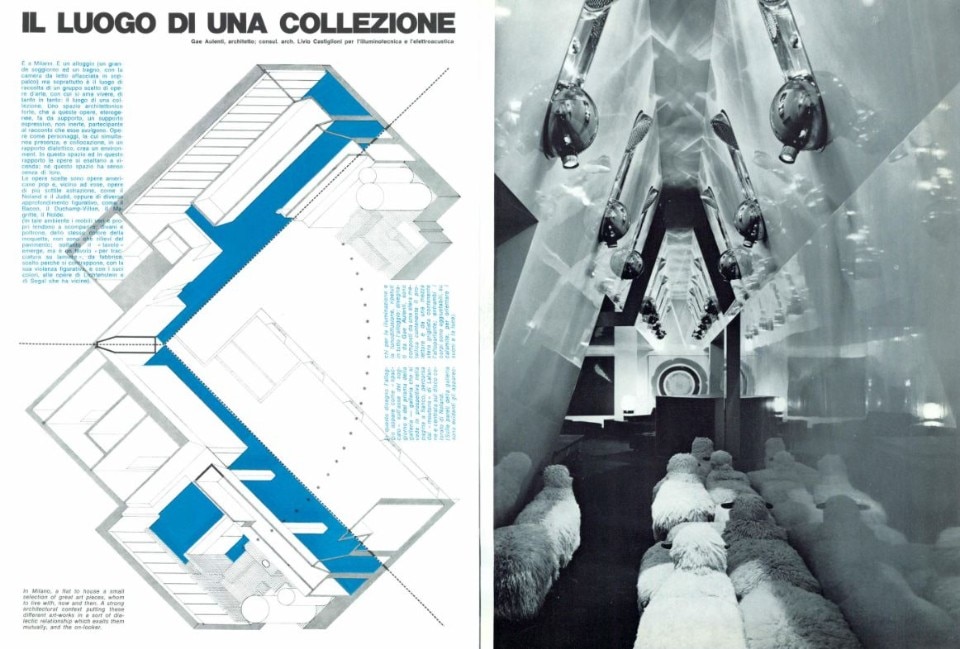

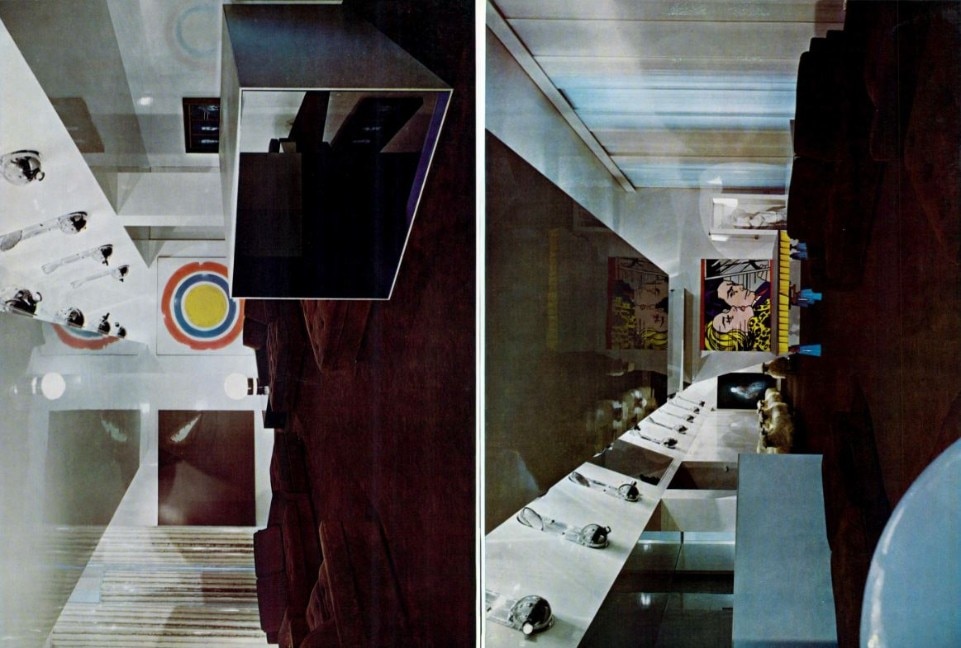

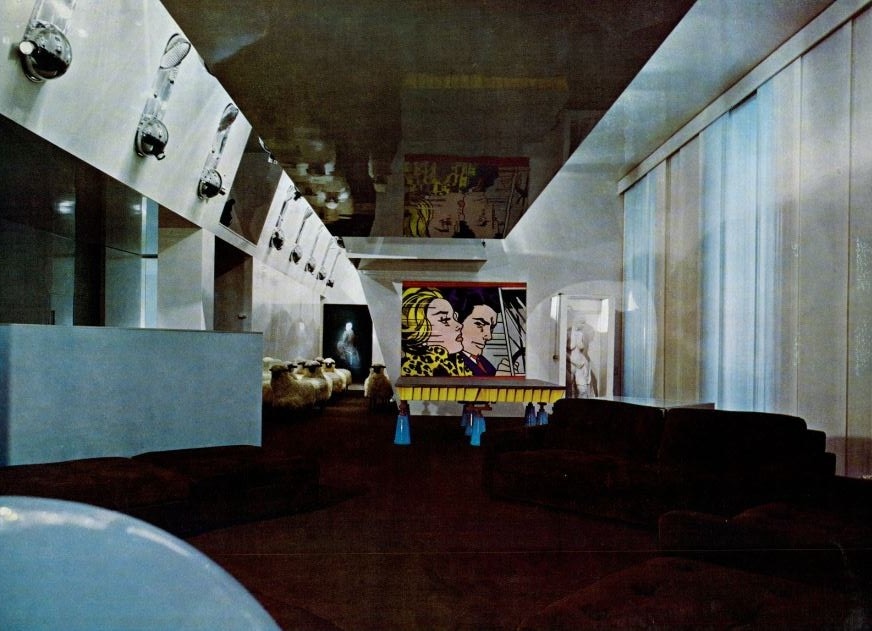

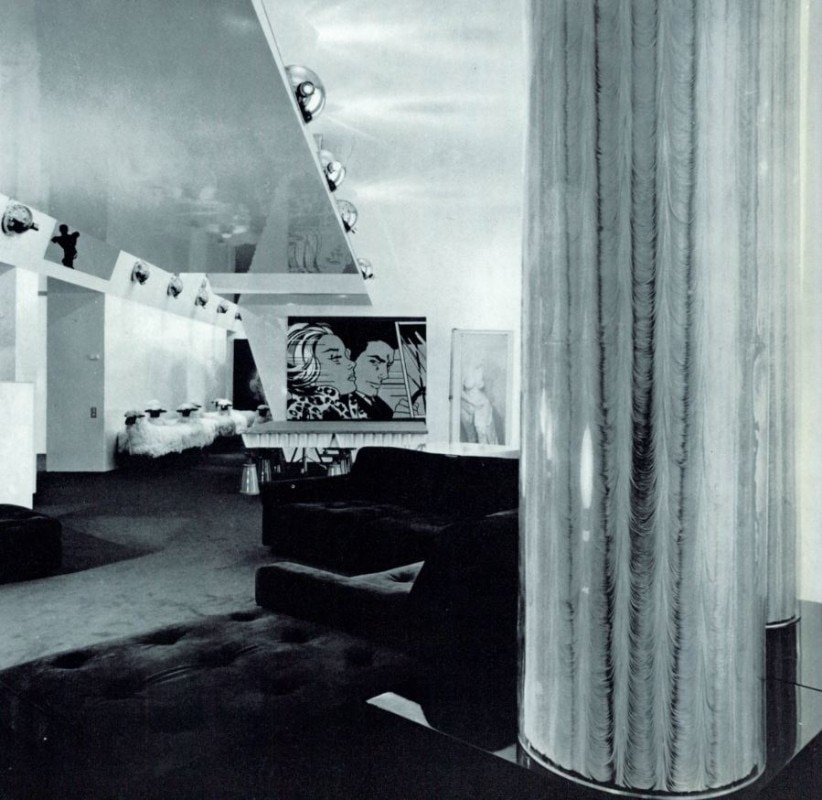

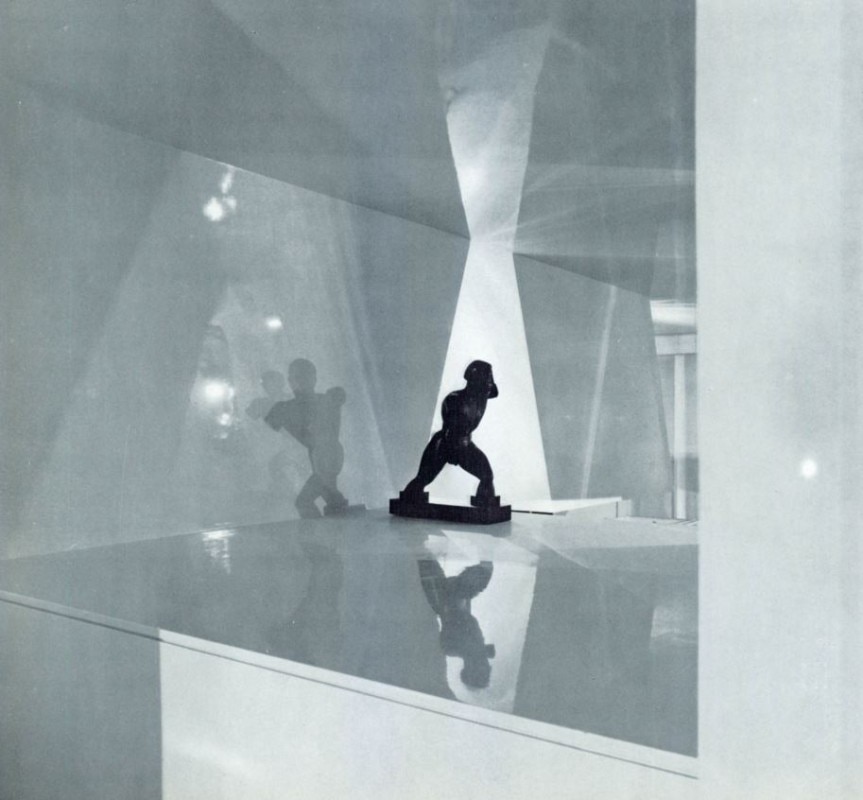

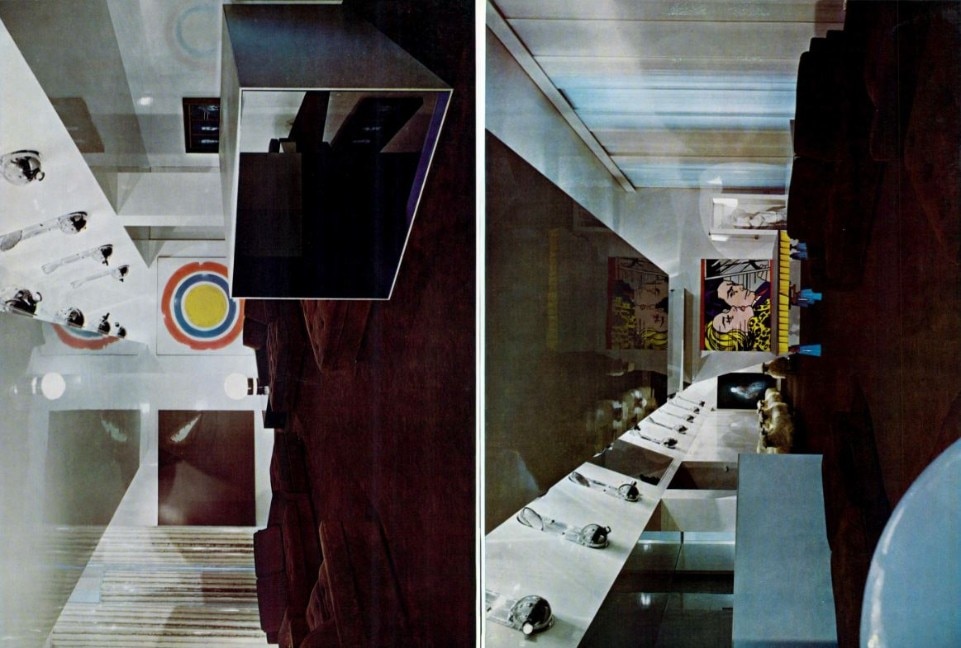

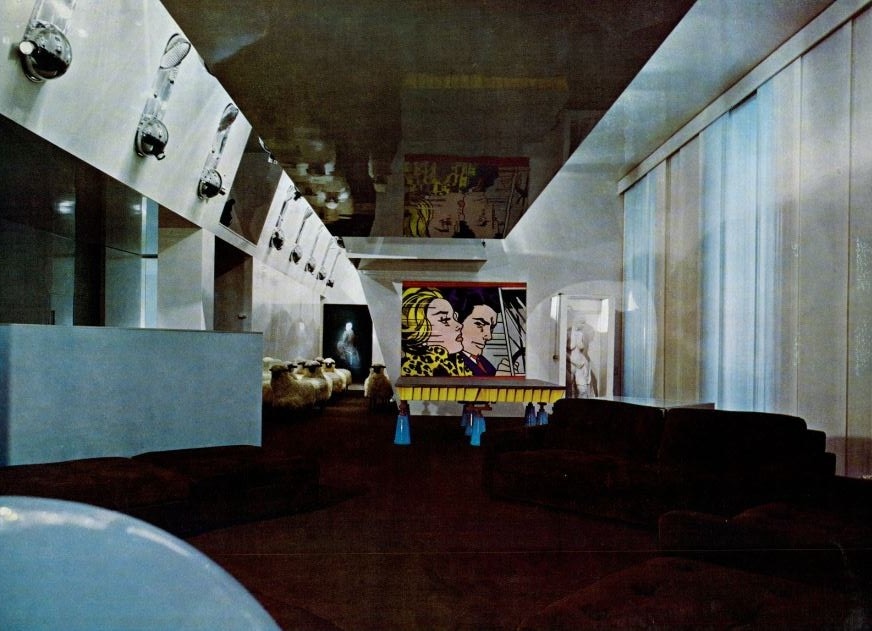

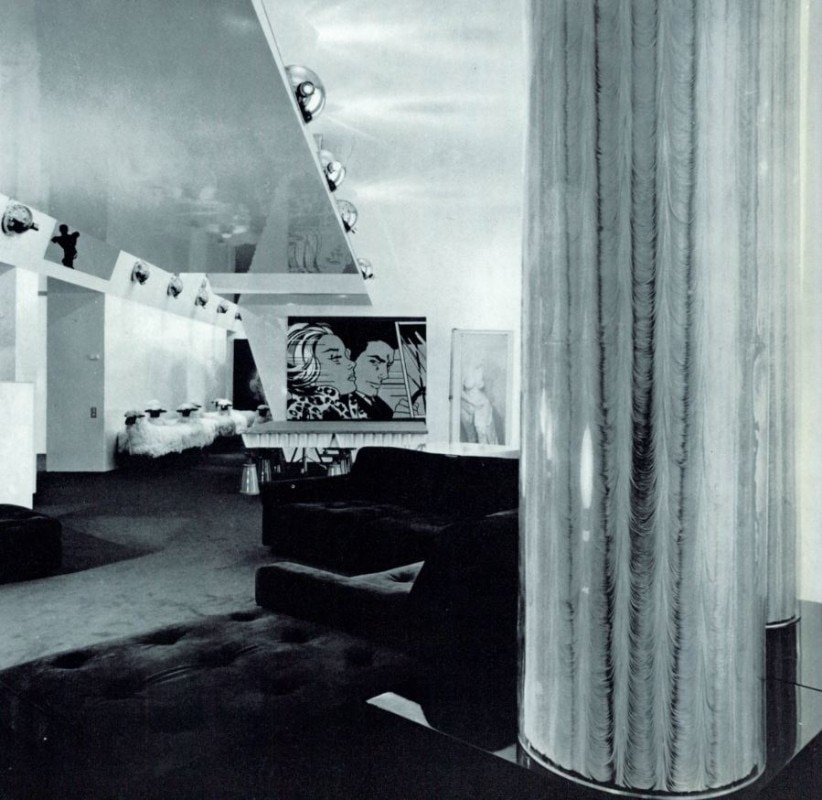

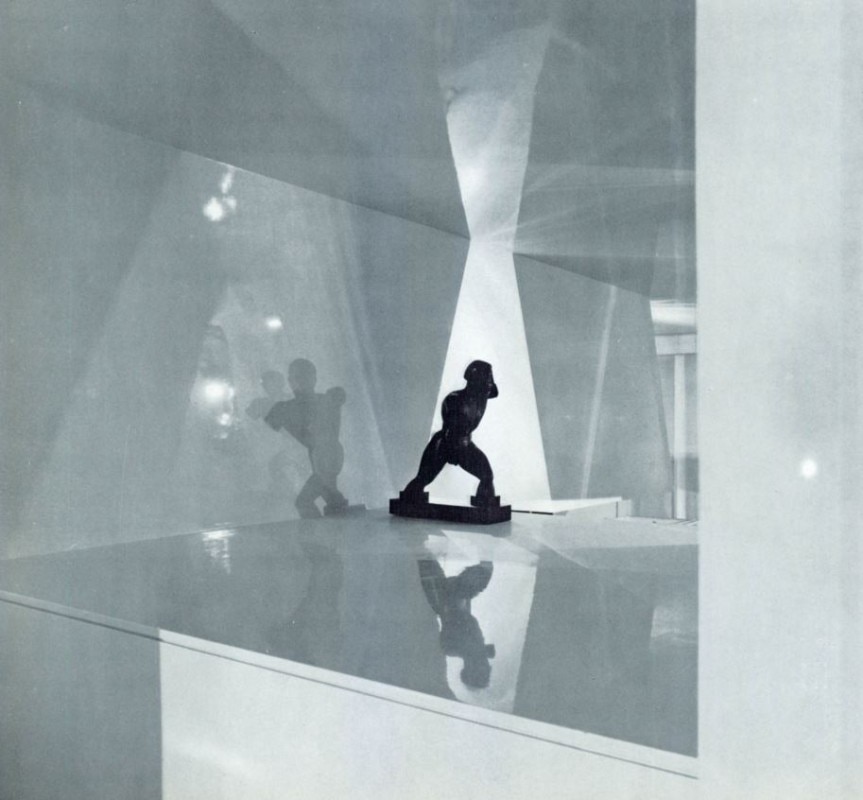

For the Agnellis, in 1969 Aulenti also designed an apartment in Milan, the so-called House of the Collector, where once again the idea of scenic enjoyment returned, and of a space entirely organized around a collection of artworks.

Furniture disappeared, sofas and armchairs blending with the carpet in colour and materiality; what resisted—like the large sheet-metal table supported by blue truncated cones—did so precisely to dialogue with the artworks, enhancing them. Among a Duchamp-Villon, a Magritte, and a Lichtenstein, the domestic space lent itself this time as a silent support to an orchestrated scenography.

View gallery

View gallery

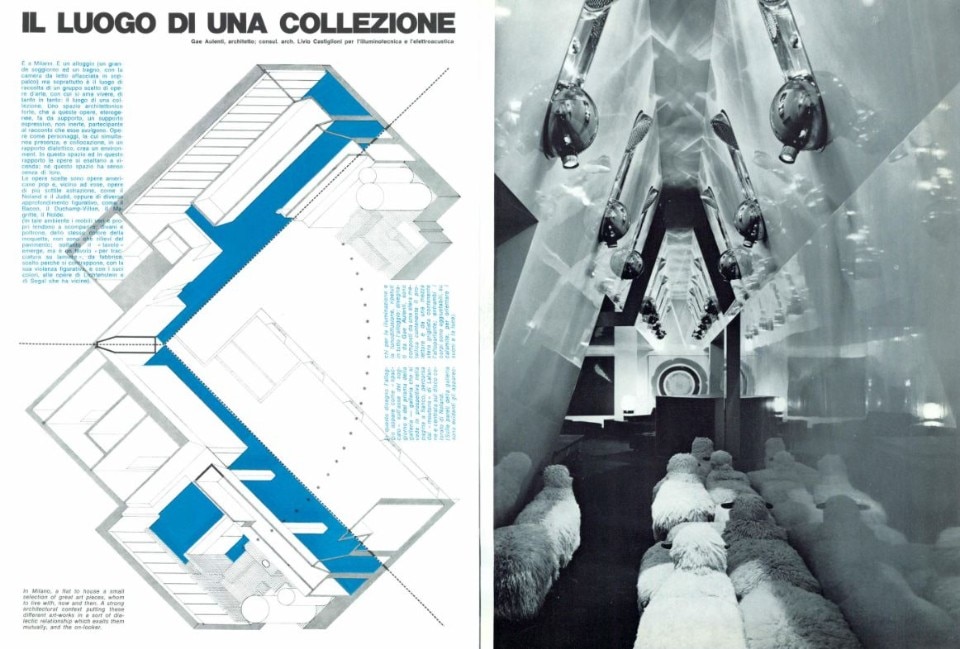

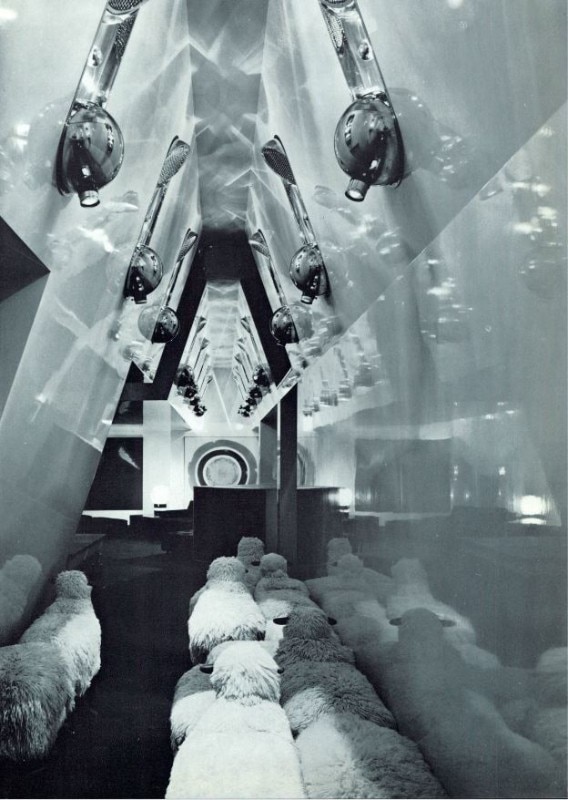

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

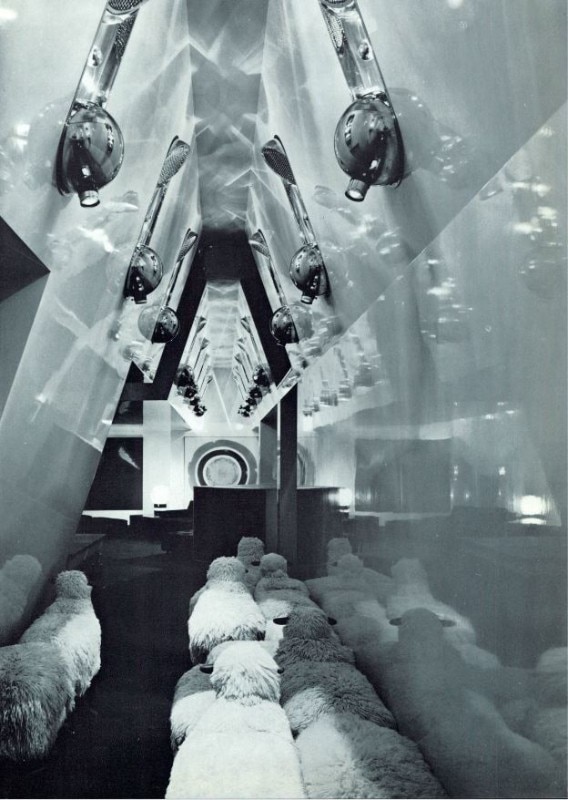

In this drawing, the apartment appears as split on the axis of the living room and the gallery prism ─ a gallery that can be seen in perspective on the opposite page, traversed by Lalanne's "moutons" and centred on Noland's coloured disc. (On the walls of the gallery the lighting and sound diffusion devices are evident, repeated throughout the room: designed by Gae Aulenti, they are composed of a metal sphere containing the projector and a grated half sphere containing the loudspeaker; both bodies can be adjusted, on magnets, to direct sound and light).

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

In this drawing, the apartment appears as split on the axis of the living room and the gallery prism ─ a gallery that can be seen in perspective on the opposite page, traversed by Lalanne's "moutons" and centred on Noland's coloured disc. (On the walls of the gallery the lighting and sound diffusion devices are evident, repeated throughout the room: designed by Gae Aulenti, they are composed of a metal sphere containing the projector and a grated half sphere containing the loudspeaker; both bodies can be adjusted, on magnets, to direct sound and light).

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

"House for an art collector": the Agnelli apartment conceived in MIlan by Gae Aulenti

Domus 482, January 1970

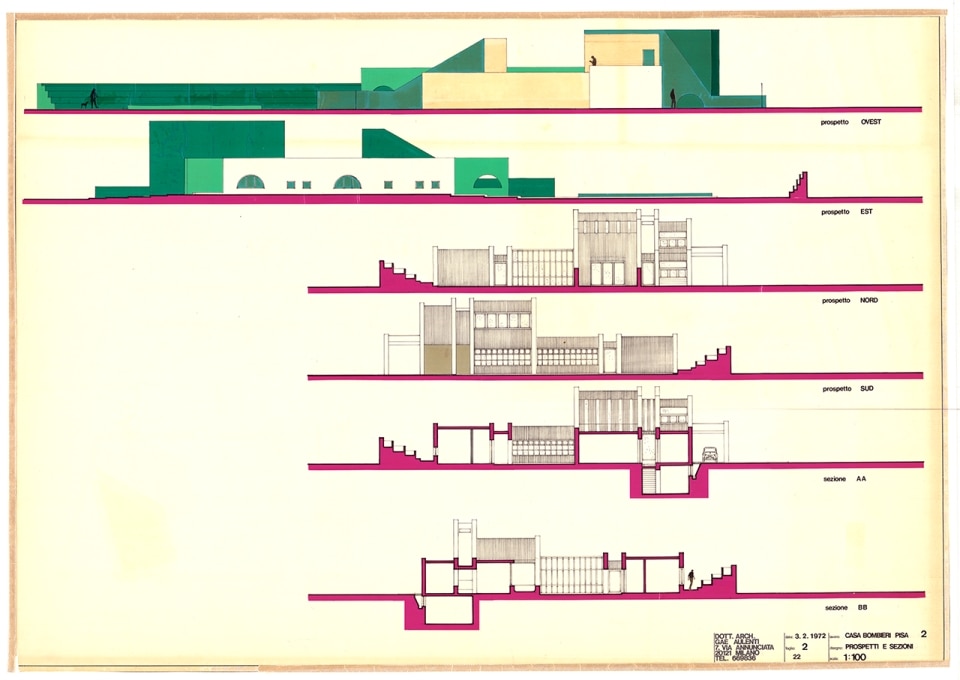

Beyond these experiments, in the early 1970s “La Gae” immersed herself in themes of domesticity, refining concepts she had already explored in her Villa in the Woods (1963). She designed for herself a villa in Capalbio in 1971 (never realized), then the Villa in Parma for Clemente Papi (1973), and one for Plácido Arango Arias in Formentor, Spain (1974, also unbuilt), all conceived with offset nuclei organized around patios and courtyards; the villa built in Pisa in 1973 for Enrico Bombieri would prove even more original.

With this “house of parallel walls,” Aulenti explored the potential of the wall as the guiding element in spatial genesis. The entire structure emerged from the staggering and juxtaposition of a complex system of parallel masonry filters and diaphragms, between which the different rooms were set, with a system of openings that expanded interior views: any principle of rigid symmetry was overturned in favour of a constant search for new systems of spatial organization—an approach that would also be transposed to the urban scale.

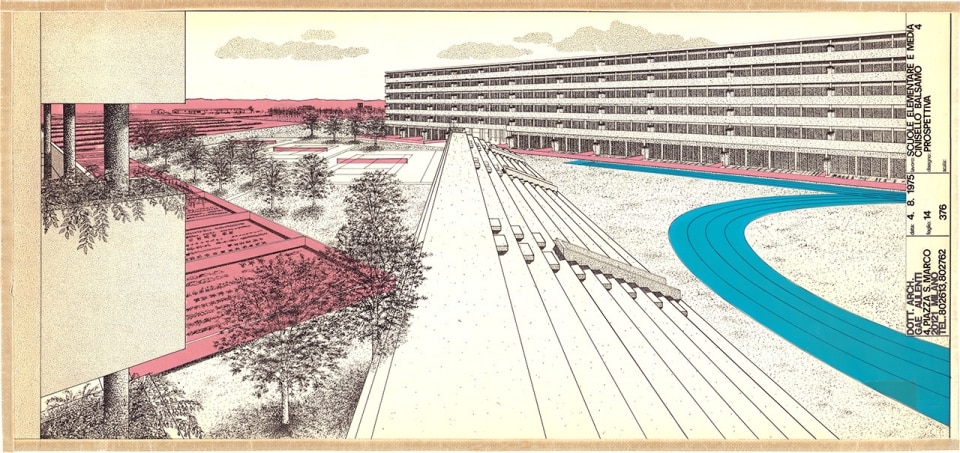

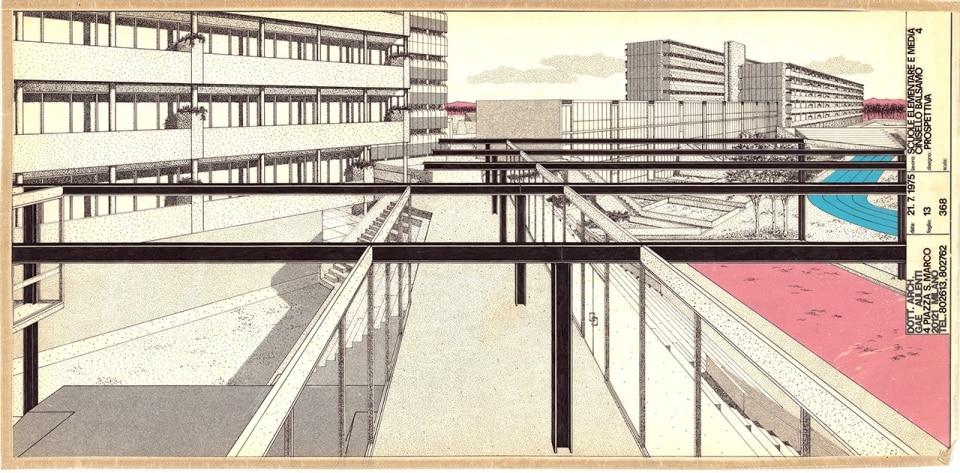

Indeed, the 1970s marked the beginning of her large urban plans, and in Cinisello Balsamo, in the same year as the Pisa project, Aulenti proposed a residential development with schools, once again organized around the parallel axes of inhabited “masonry bands,” with diagonal insertions for services, all firmly held together by a grid of beams and pillars that gave the project drawings the sense of endless spatial progression.

Then came the Musée d’Orsay, apex and true sublimation of Gae Aulenti’s career, the constant perseverance of her work carried out within the limits imposed on the lone woman who, “always pretending nothing was amiss,” insisted on practising a profession considered essentially “male.” Winner of the 1980 competition in Paris to transform the disused Gare d’Orsay into a museum of 19th-century art, the project entailed, on the one hand, restoration of the existing building and, on the other, the clear independence of all new interventions. Above all, as in the House of the Collector, it was the artworks’ path that determined the architecture. The site lasted six years, and in Gae’s own words it was “a continuous struggle,” starting with the challenge of making the station’s iron vibrations coexist with works of art that “cannot live within vibrations.”

Like all great gambles (and as had already happened with its cousin, the Beaubourg, though so different in premises and results), once inaugurated the Orsay was not universally liked, but as Aulenti herself said: “if everyone likes you, something is wrong.” Yet even today, in those sober and respectful choices, in that valorization of collections through materials chosen by the architect—such as the light-coloured limestone (perfectly enhancing the natural light coming from the station’s original vault, combined with the interior lighting design by Piero Castiglioni)—resides the project’s profound intelligence.

Naturally, Aulenti’s architecture led her to theatre: for her, it was simply another possible space to experiment with language and spatial construction; indeed, it was perhaps in this context, at least in Italy, that she expressed herself most freely.

Her encounter and collaboration with Luca Ronconi, starting in 1974, proved fundamental to developing a new idea of scenography, where scenic space was essentially concrete space: no longer a container to be decorated, but a structure made of solids and voids, of light and shadow, of rhythm and pauses—just like architectural space. For The Tale of Tsar Saltan, staged in May 1988, Aulenti went so far as to transfigure this scenic-architectural space, simultaneously representing three dimensions and multiple viewpoints.

If everyone likes you, something is wrong.

Gae Aulenti

The fortified city towers of the Tsar were seen from above, as was the stage backdrop—a stormy sea also rendered from a “skyward” perspective. From prologue to epilogue, muffled or dazzling atmospheres unfolded, with a surreal, fairytale-like tension constantly evoked by floating elements suspended in midair, culminating in the final scene, where diners at a richly laid table suspended in the middle of the stage sat and feasted around it, defying gravity itself.

“Minor,” though only in scale, was her work in design. The Table with Wheels, produced by FontanaArte in 1980, once again synthesized that coexistence of rigor and play that, in her own original way, never left Aulenti’s personality and oeuvre. With an apparently simple move, yet born of refined and ingenious thinking, Aulenti took the trolleys used in factories to transport glass sheets and reimagined them, inserting industrial wheels with metal forks beneath a glass top, producing the estranging—and brilliant—effect she had cherished since The Arrival at the Sea, where this story began.

Thus, in continuing to celebrate the work of this great master today, it seems fitting to borrow once more the words of Manfredo Tafuri, who with the sophisticated acumen of a historian described her architecture as a perfect symphony of “exhausted geometries” and “rarefied elegance.”

Opening image: Photo Gorup de Besanez, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons