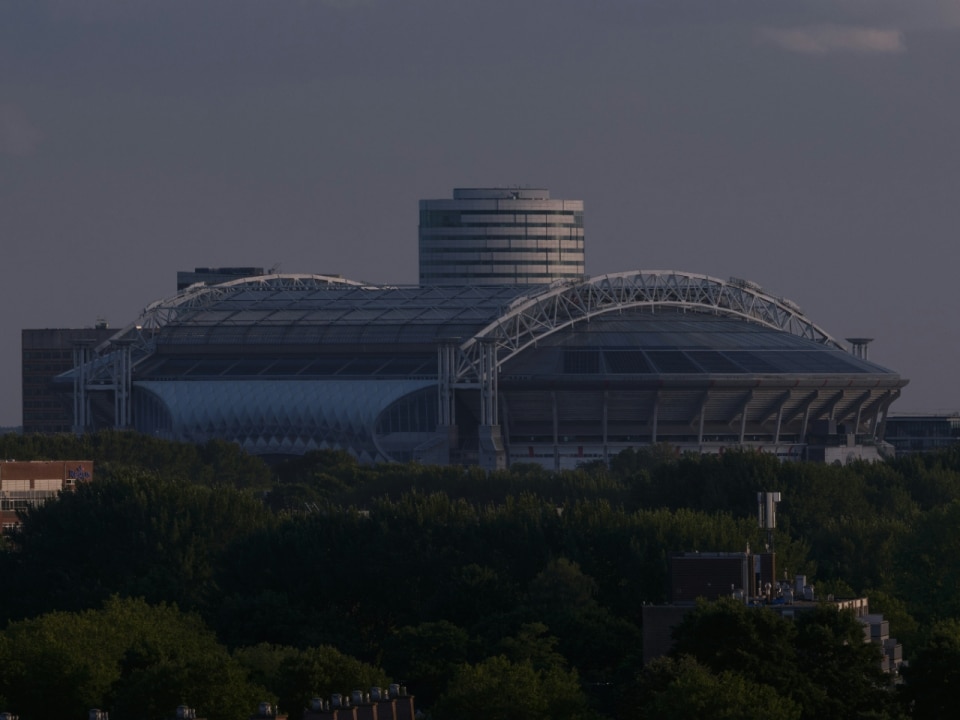

“Luci a San Siro” is a classic of Italian pop music from 1971. Sung by singer-songwriter Roberto Vecchioni, it tells the story of a love gone awry, which broadens into an ode to youth, to Milan, and to the San Siro neighbourhood – home to the legendary stadium of AC Milan and Inter Milan. In recent years, the song has been cited increasingly often, becoming the resigned lament and melancholic soundtrack to the mounting rumours surrounding the demolition of one of Italy’s (and world’s) most beloved football grounds.

After months of uncertainty, and following the Milan City Council’s recent approval of the sale of the ground to private ownership after ninety years (that is, to FC Internazionale Milano and AC Milan), the two clubs have now signed the deed of sale, a prelude to the much-discussed demolition. From the 253-page dossier submitted by the two clubs, the current plan appears to suggest an almost complete demolition of the stadium, with the remaining portion to be converted into a museum.

Milan thus seems, footballistically speaking, to be edging closer to another spectacular own goal – not unlike the quiet summer demolition of Ignazio Gardella’s 1958 Agriculture Pavilion, which was torn down amid the city’s deserted streets at the end of July.

Losing our football grounds would mean losing a part of Italy’s identity. By conforming to international trends we would also be relinquishing that provincial spontaneity.

In San Siro’s case, the real risk was failing to heed the warning signs. Football-wise, we may be staring down another own goal for Milan – not unlike the quiet summer demolition of Ignazio Gardella’s 1958 Agriculture Pavilion, which was torn down amid the city’s deserted streets at the end of July.

San Siro’s predicament mirrors that of other historic grounds: Manchester’s Old Trafford, Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge, Newcastle’s St James’ Park, Valencia’s Mestalla, whose clubs are all weighing up new architectural projects. While Europe’s footballing old guard struggles under the social and structural weight of its ageing stadiums, the brave new world takes a radically different view. Take Qatar’s Stadium 974, built for the 2024 FIFA World Cup from shipping containers and designed to be dismantled.

View gallery

View gallery

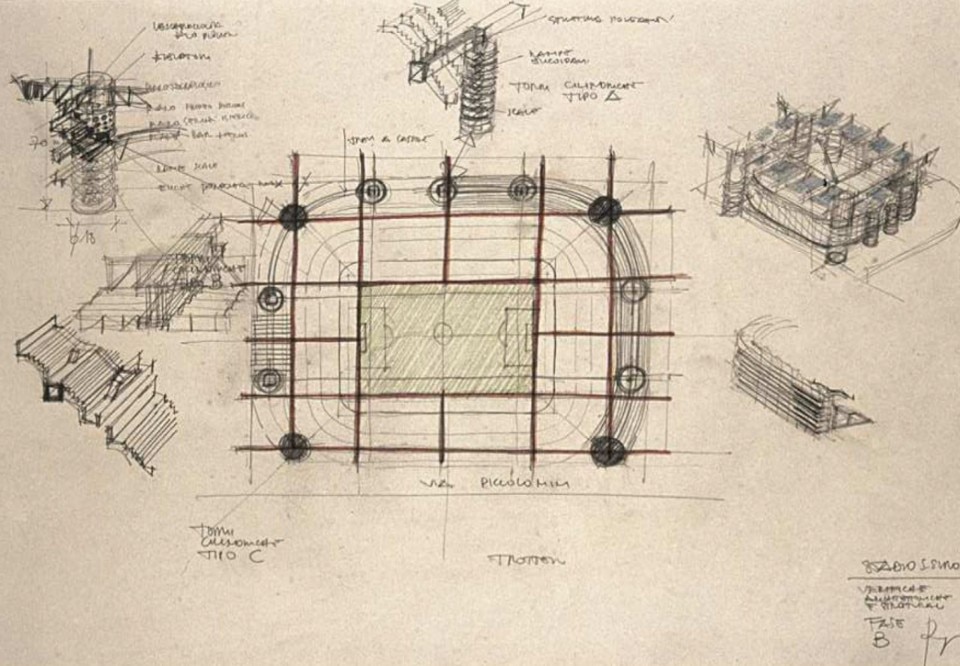

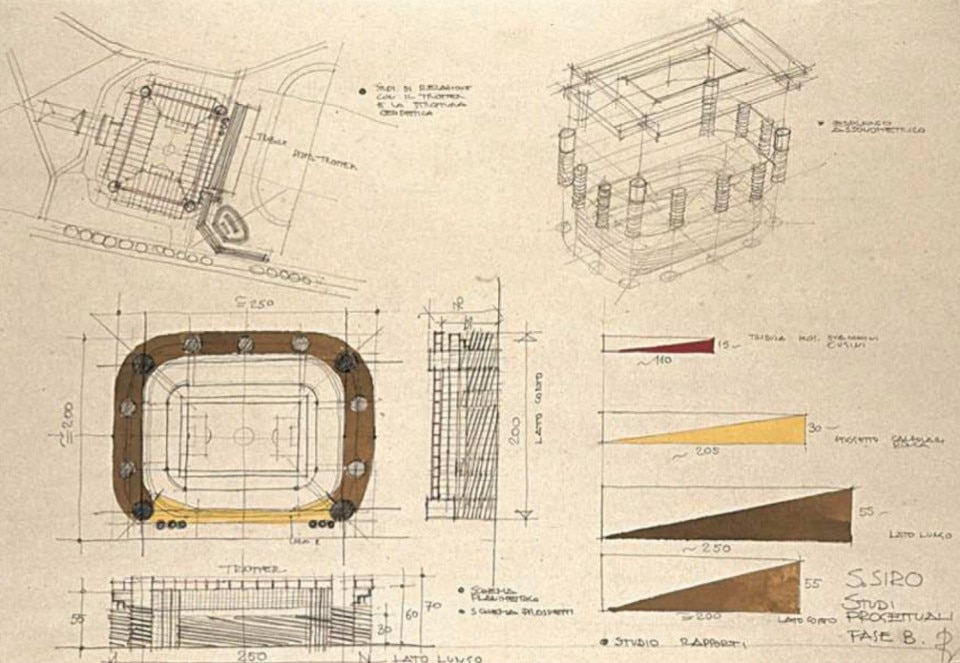

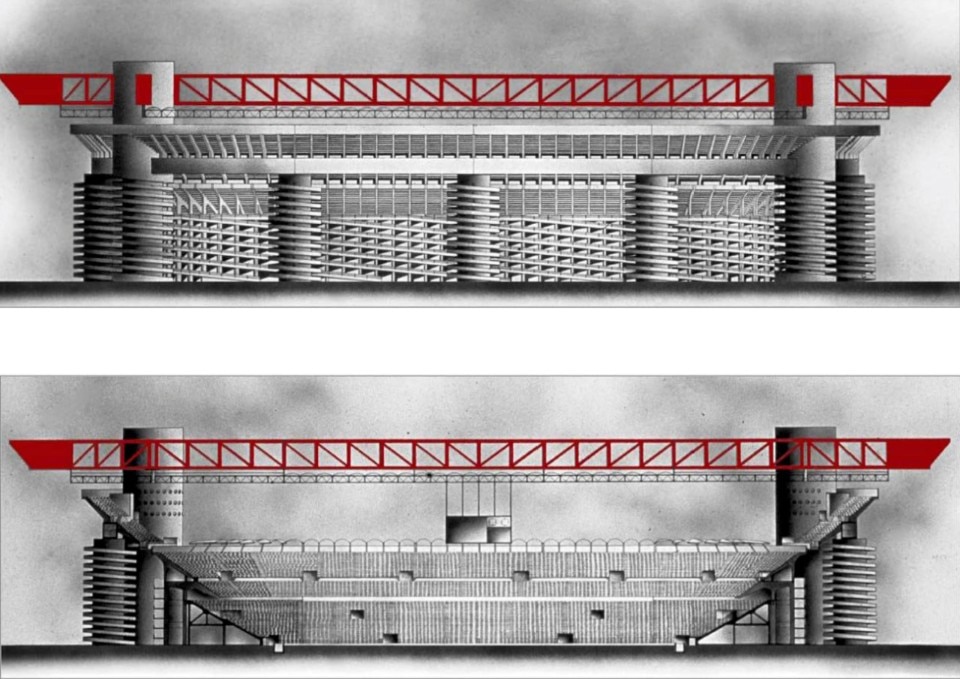

The San Siro case opens a crucial debate: that of safeguarding historic sporting architecture. It’s no secret that many Italian stadiums are swiftly approaching the end of their life cycle. Often built between the 1920s and 1930s as part of Fascist propaganda efforts, they were, at best, renovated (not always tastefully) for the Italia ’90 World Cup – the last flourish of Italy’s Craxian grandeur. As a matter of fact, in recent months there had been discussions about removing the third tier of San Siro – originally designed for the World Cup by Giancarlo Ragazzi (former Prime Minister and AC Milan chairman Silvio Berlusconi’s trusted architect, and the mind behind the Milano 2 and Milano 3 settlements) – and replacing it with a commercial and dining gallery. Similarly, at Florence’s Artemio Franchi, the ongoing restoration aims to remove the Italia ’90 additions in order to preserve the listed Pier Luigi Nervi original 1931 structure.

Football is changing, and so are its economics. Clubs now demand venues that are flexible and profitable, not just on matchdays but through non-sporting uses as well – to be transformed into event spaces, shopping hubs, hotels, or club museums, as with Juventus’ Allianz Stadium, the only Serie A ground owned outright by its club. It would be naïve to expect today’s football corporations to act out of love for their city or its history when there’s no financial incentive to do so. Loyalty, in football, remains the province of the fans. And it would be equally naïve to hope for a romantic gesture from Milan and Inter, two clubs whose connection to their city is now mostly limited to their headquarters.

The challenge is immense. To decommission a stadium does not simply mean preserving its documents, memorabilia, seats, scoreboards and gates. It means acknowledging the emotional and local significance the structure embodies: something that extends well beyond its walls. In cities where buildable land is scarce, the trend of moving stadiums to the extreme edge of the metropolitan (or even beyond it) risks eroding the very heart of the sporting community. A new stadium takes years before it feels like home to its supporters.

Decommissioning a stadium is not just preserving documents, memorabilia, seats, scoreboards, and gates; it also means recognizing the emotional and local significance that extends beyond its walls.

Elsewhere in Europe, adaptive reuse and architectural recycling are central themes of debate. In Italy, however, the role a stadium can – and should – play within the urban fabric remains an open question. The San Siro controversy leaves these questions unresolved, not least because opposition to its demolition has been remarkably subdued. It was, in fact, The Guardian that reignited the debate from abroad, arguing for the protection of a building that is “an instantly recognisable setting, in an era when too many other venues tend towards the familiar.”

Where reuse is hard to achieve – as it often is in Italy, where the idea of architectural afterlife is still marginal – it becomes all the more important to encourage critical, culturally rooted projects rather than those driven purely by marketing and the homogenising logic of global sports branding. A case study from the Italia ‘90 era that remains relevant is that of Vittorio Gregotti for Genoa’s Marassi stadium.

Losing our football grounds would mean losing a part of Italy’s identity. By conforming to international trends – where the demolition of football cathedrals such as Upton Park (West Ham) and White Hart Lane (Tottenham Hotspur) has been passively accepted as the cost of modernity – we would also be relinquishing that provincial spontaneity which, even in a city as exacting as Milan, has always been a spark of vitality, passion, and belonging.

We have selected a collection of stadiums that have vanished, fallen into disuse, or lost their original identity through redevelopment.