A common thread connects New York’s High Line – one of the most influential urban interventions of this century – and Canal Café, which recently won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. The architects behind both projects are the same: Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, who founded their firm in 1979. In 2004, Charles Renfro joined the team just as New York began the ambitious High Line project, which was realized five years later. The competition sought “visionary design proposals” to transform the deteriorating elevated tracks in a once-blighted neighborhood into an innovative urban space. The idea of a suspended linear park was so impactful that it not only revitalized the Meatpacking District – turning it into a hub for major designers – but also became a model for urban regeneration worldwide.

The High Line: the virtues and limits of a visionary project

The High Line is a visionary project that has been widely imitated – every city seems to want one. From Twelve Architects’ project in Manchester to the upcoming Tokyo installation set to open in 2029, the influence of the High Line is undeniable. In this issue of Domus, Diller reflects on the project’s early stages.

“We proposed turning it into a park, as Frederick Law Olmsted did with Central Park. At first, the High Line project seemed really complicated because we didn’t know what a ‘park in the sky’ would be like. How would we make it safe? How would we get rid of the waste?” Diller recalls. Back then, the west side of Manhattan was a decaying area marked by drug trafficking, prostitution, and large swaths of abandoned space. The elevated park helped regenerate much of the city, but not without consequences.

An influx of visitors and a sharp rise in property values transformed the High Line into a gentrification engine. “Today, it’s one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods. But the residents – the artists – have been pushed out. It’s become an area for the rich, even though it remains a public park,” Diller notes. So, what could have been done to prevent this? “As architects, we wouldn’t have created a less beautiful project,” she observes. “Had we known how popular it would become, we could have imposed quotas for affordable housing. This didn’t happen, but it should in future projects.”

It is essential to adapt existing structures, but also to design new ones with an eye to the future, to what will happen in 30 or 40 years’ time

Elizabeth Diller

In response to this unchecked growth, in 2018, the studio staged The Mile-Long Opera, a performance involving 1,000 singers along the entire High Line, narrating the stories of those displaced by the project. This was a clear, almost self-critical answer to the contradictions inherent in their own creation.

The Golden Lion in Venice could have been awarded years ago

While the High Line was taking shape, DS+R was also working on another project – the Canal Café – which only came to fruition this year, the same year that Ricardo Scofidio, Diller’s partner in both work and life, passed away.

“In 2008, the project was terminated abruptly during its final design. We never understood why,” Diller shares. The Canal Café structure is entirely transparent, with the Corderie dell’Arsenale visible from every step of the process. Today, its message is even stronger. “This opportunity for the café-laboratory to be situated so visibly at the lagoon, drawing water from it, is a more powerful statement now than it would have been in 2008. Concerns about water degradation and depletion have never felt more urgent.”

The instability of architecture can make it durable

Time is a recurring theme for Diller. “We live in an age of rapid change. And architecture seems so slow. A lot of time passes between the design and construction of a building, and then it stands there, permanent and difficult to adapt, unless adaptability is taken into account from the beginning,” she says, discussing her research for the "Restless Architecture" exhibition at MAXXI in Rome. The show highlighted historical and contemporary examples of architecture that embraced “instability” as a design principle, including Maurizio Sacripanti’s Italian Pavilion at Expo 70, Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe, Angelo Invernizzi’s Villa Girasole, and OMA’s Maison à Bordeaux.

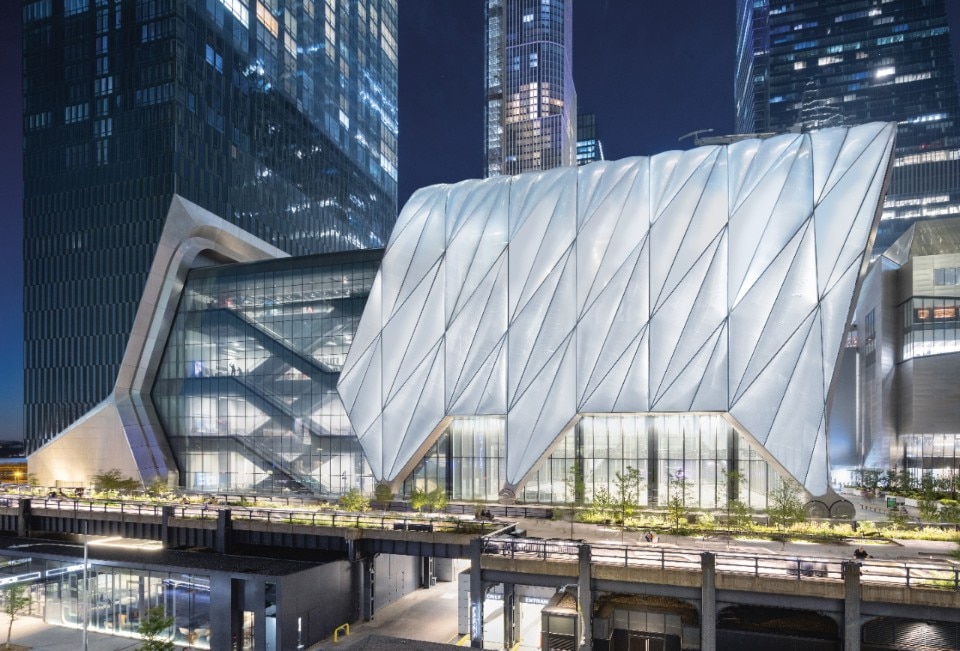

One example of this concept in action is The Shed, a piece of movable architecture designed by DS+R. This building can expand and contract by rolling its telescopic shell along rails, adjusting its covered space as needed.

Designing cities, leaving space for the future

The story of the High Line is also one of a project that never came to be. In 1999, while the competition to redevelop Manhattan’s West Side was underway, Diller was on the jury. “I remember sitting there with all these older white men and wondering: ‘What am I doing here?’” she recalls. “Everybody else – like Peter Eisenman and the other architects – was proposing huge buildings, as if filled with architecture.” There was one exception: Cedric Price, the architect behind the Fun Palace, who argued that nothing should be built at all, allowing the city to breathe, as it was already densely developed. “Don’t take another open space and plug it with buildings,” he said. Diller remembers his almost empty drawings: “I thought it was brilliant.”

Price’s ideas continued to influence Diller’s approach. The Blur Building of 2002, for example, is an installation made of fog where visitors see everything as “blurry” – a stark contrast to the high-definition trend of that period. More recently, DS+R’s masterplan for Milan’s Parco Romana adopts a similarly unconventional approach: “No perfect lawns, but a wilder and more varied nature,” Diller explains. Like New York, this project also involves the regeneration of an old railway infrastructure.

I hope that, in the future, architects and planners will be more involved in the growth of cities.

Elizabeth Diller

But, Diller points out, a masterplan alone isn’t enough. Cities need vision and thoughtful design. “With climate change and urban growth, cities will become increasingly dense. It’s essential to adapt existing structures, but also to design new ones with an eye to the future, to what will happen in 30 or 40 years’ time,” she says. “It’s not enough to build new residential or office districts. We need schools, culture, shops, and parks.” Her hope is that “architects and planners will be more involved in the growth of cities” – and that they will stop “building higher and higher, as if to win the race for the tallest skyscraper.”

Opening image: Elizabeth Diller, photo Geordie Wood