In many Venetian calli — now turned into liquid corridors — the water reaches your knees; but if you lift your gaze, a network of walkways connects terraces and rooftop altane. Ground floors are no longer inhabited: many entrances and shops have become amphibious spaces, while life has moved upward. The MOSE system, once conceived as a defensive barrier against high tides, now acts more like a membrane that stabilizes an uncertain equilibrium.

A parallel-world Venice? Or a glimpse of its future? In recent years many have imagined it underwater: from novels (Le acque di Venezia, Ultima) to academic projects (Project Venezia 2100: Living with the Water) to interactive visualizations (Venezia +6m, Venice Underwater). The fragility of the lagoon city has become the unspoken premise of the latest Biennales.

If sustainability becomes a trend, then it disappears.

Lina Ghotmeh

Since the 1990s, sea levels have continued to rise, and between 2010 and 2019 there were forty episodes of acqua alta above 120 cm — a dramatic increase compared to a century ago. Venice lives in the past but already inhabits the future: one in which water is no longer an emergency, but a permanent condition.

Fragile cities and the reality of climate change

Returning to our present world — our Earth-616, to borrow from Marvel comics — Piazza San Marco is already preparing for high tide, walkways laid out, on the final day of the Holcim Foundation Forum. Retreat, resist, respond were the keywords: urban thinkers, environmental scientists and design practitioners confronting flooding and sea-level rise — “one of the defining climate challenges of our time.” The aim: rethink how we inhabit water-vulnerable cities. From the crisis of Jakarta to coastal communities swept away by storms, the Forum offered a sharp, lucid view of today’s unfolding apocalypse. In parallel, the Holcim Awards ceremony — one of the world’s leading recognitions for sustainable architecture and construction.

Sustainability is social before everything else. If people don’t want to use a space, it cannot be sustainable.

Kjetil Thorsen, Snøhetta

View gallery

View gallery

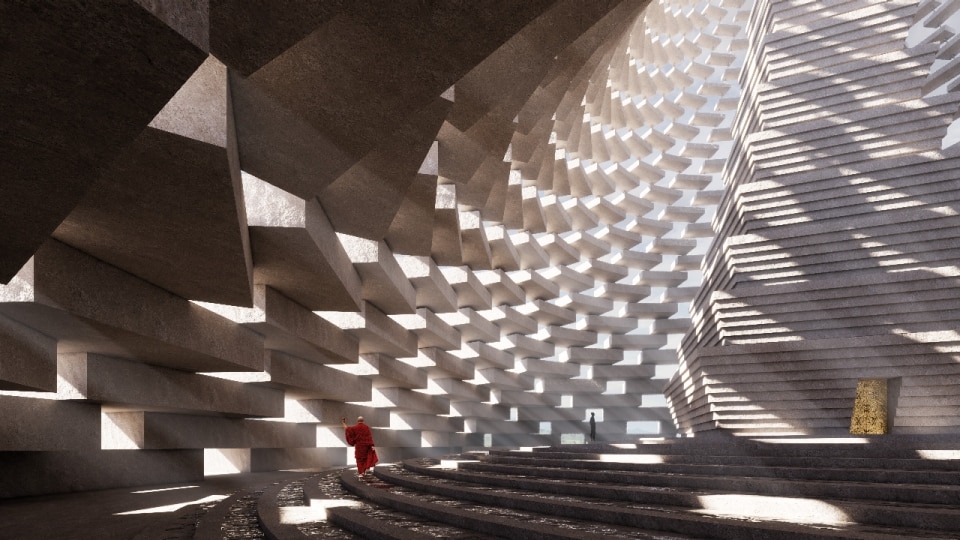

Gelephu Mindfulness City - Gelephu, Bhutan | BIG – BJARKE INGELS GROUP

In Bhutan, the Gelephu Mindfulness City designed by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group envisions a new spiritual and economic capital built on harmony between people and nature: neighborhoods that follow the natural valleys, local materials, hydropower, and urban farming come together in a holistic – and seemingly replicable – urban model.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Gelephu Mindfulness City - Gelephu, Bhutan | BIG – BJARKE INGELS GROUP

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

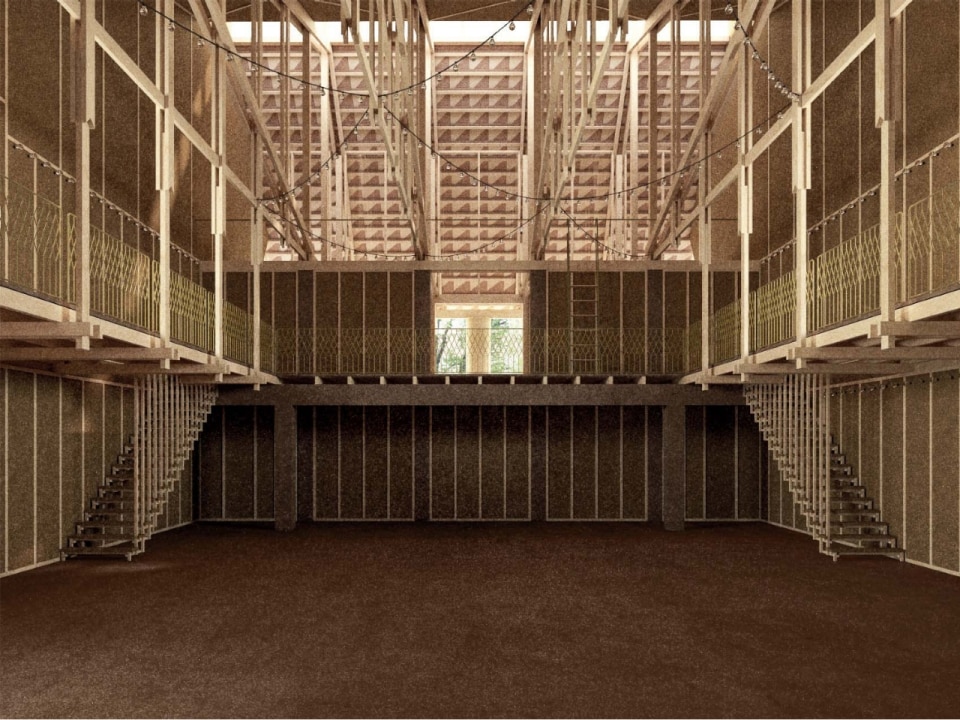

Healing Through Design - Bengaluru, India | THE AGAMI PROJECT / A THRESHOLD

In Bangalore, the Healing Through Design project by The Agami Project and A Threshold draws inspiration from the Japanese art of kintsugi: reclaimed materials and construction waste are transformed into a health and training center that restores dignity and beauty to urban fragilities.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Healing Through Design - Bengaluru, India | THE AGAMI PROJECT / A THRESHOLD

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Old Dhaka Central Jail Conservation - Dhaka, Bangladesh | FORM.3 ARCHITECTS

In Bangladesh, the conservation of Dhaka’s former Central Jail by FORM.3 Architects places memory at the heart of urban life, transforming a symbol of confinement into a public park, museum, and community space. According to the jury, the project “retains and rehabilitates historic structures, adds appropriately scaled new buildings, and even integrates a needed public road through the site to ease traffic, all without losing sight of the community’s needs.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Old Dhaka Central Jail Conservation - Dhaka, Bangladesh | FORM.3 ARCHITECTS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Pingshan River Blueway Landscape - Shenzhen, China | SASAKI ASSOCIATES, INC

In Shenzhen, the Pingshan River Blueway Landscape by Sasaki Associates revitalizes 40 kilometers of riverbanks with a “holistic vision,” combining biodiversity, natural drainage, and accessible public spaces within a large urban ecological corridor.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Pingshan River Blueway Landscape - Shenzhen, China | SASAKI ASSOCIATES, INC

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Art-Tek Tulltorja - Pristina, Kosovo | RAFI SEGAL A+U, OFFICE OF URBAN DRAFTERS, ORG PERMANENT MODERNITY, STUDIO REV

In Pristina, Kosovo, Art-Tek Tulltorja (by Rafi Segal A+U, Office of Urban Drafters, ORG Permanent Modernity, Studio REV) transforms a former brick factory into an art and technology center, turning a site of industrial memory into a hub for community innovation. The jury noted that in post-conflict Kosovo, this project – which embraces environmental remediation, cultural programming, and economic development – could have a profound impact.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Art-Tek Tulltorja - Pristina, Kosovo | RAFI SEGAL A+U, OFFICE OF URBAN DRAFTERS, ORG PERMANENT MODERNITY, STUDIO REV

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

School in Gaüses - Girona, Spain | TED'A ARQUITECTES

In Spain, the School in Gaüses by Ted’A Arquitectes reimagines the rural school as an ecological micro-campus, built with local rammed earth, wood, and cork, where learning extends into the natural environment.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Crafts College - Herning, Denmark | DORTE MANDRUP

In Denmark, The Crafts College by Dorte Mandrup is a campus that combines school, housing, and workshops for construction techniques. The jury particularly praised its social mission: “Using design to champion under-prioritized craftspeople, the project affirms that beautiful, context-rooted architecture can instill pride, know-how, and excellence in its users.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Southern River Parks - Madrid, Spain | ALDAYJOVER ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE

The second Spanish project awarded is The Southern River Parks by Aldayjover Architecture and Landscape, which redesigned a thousand hectares along Madrid’s Manzanares and Gavia rivers, creating a green system that counters desertification and promotes urban agriculture.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Southern River Parks - Madrid, Spain | ALDAYJOVER ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing - Asunción, Paraguay | MOS ARCHITECTS & ADAMO FAIDEN

In Asunción, MOS Architects & Adamo Faiden tackle housing vulnerability through a participatory approach: Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing consists of modular homes, local materials, and shared public spaces that help mend the social fabric.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing - Asunción, Paraguay | MOS ARCHITECTS & ADAMO FAIDEN

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

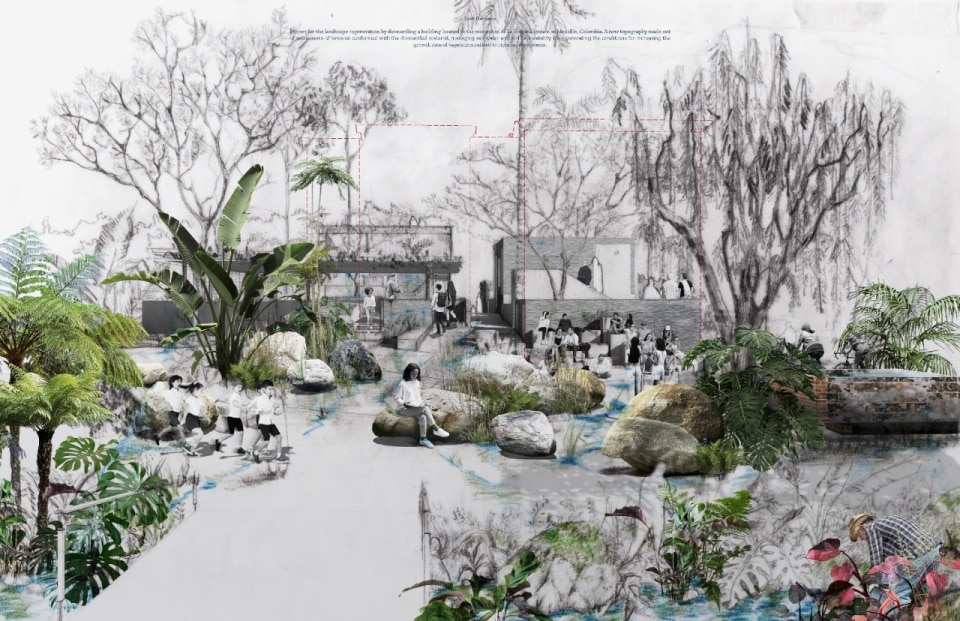

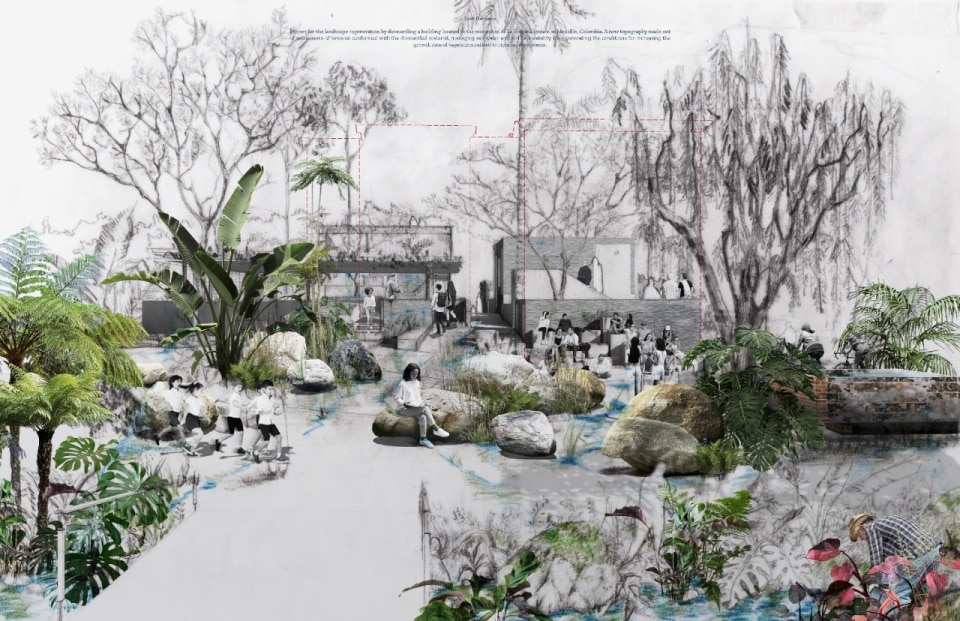

Return of the Lost Gardens - Medellín, Colombia | CONNATURAL

In Medellín, the Return of the Lost Gardens project by Connatural “deconstructs” a university building to uncover a hidden stream, creating a teaching garden and a biodiversity laboratory.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Return of the Lost Gardens - Medellín, Colombia | CONNATURAL

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Schools for Flood-Prone Areas - Porto Alegre, Brazil | ANDRADE MORETTIN ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS, SAUERMARTINS

In Porto Alegre, Brazil, Schools for Flood-Prone Areas by Andrade Morettin Arquitetos Associados and Sauermartins raise classrooms and transform rooftops into community shelters, offering a replicable model for flood-prone regions.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Schools for Flood-Prone Areas - Porto Alegre, Brazil | ANDRADE MORETTIN ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS, SAUERMARTINS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

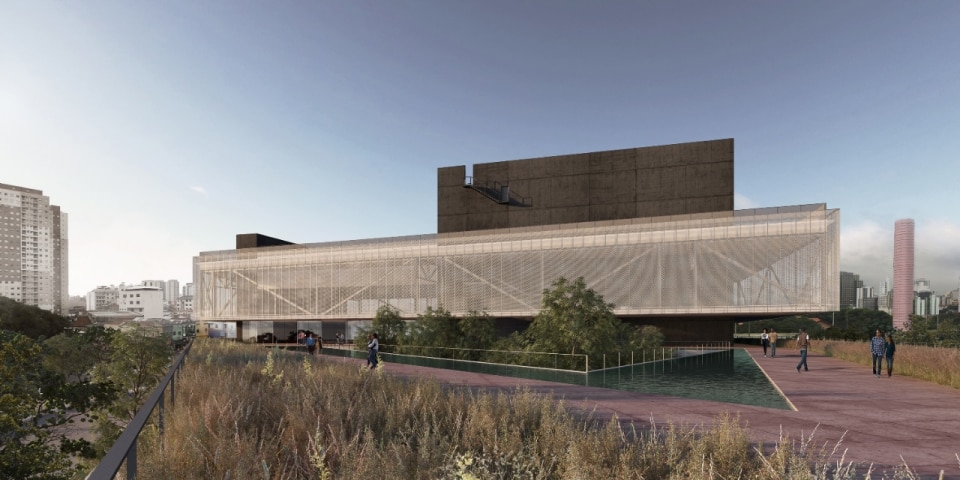

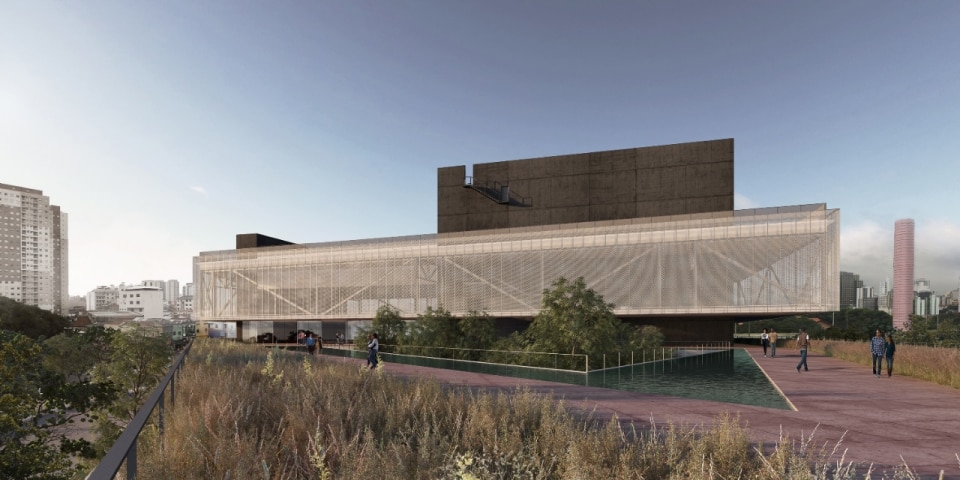

Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II - São Paulo, Brazil | UNA ARQUITETOS

The Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II in São Paulo transforms a degraded area into an inclusive civic center, hosting spaces for sports, education, and culture in the heart of the metropolis. The Jury highlighted the project’s ability to insert meaningful public space “where there was apparently no way to do something,” significantly improving the quality of life in São Paulo’s historic center.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II - São Paulo, Brazil | UNA ARQUITETOS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Brookside Secondary School - Asaba, Nigeria | STUDIO CONTRA

Many of this year’s awarded projects are schools. In Nigeria, Brookside Secondary School by Studio Contra combines climate-responsive architecture, local materials, and traditional techniques: built with locally made clay bricks, the campus employs the traditional barrel vault, arches, and “hit-and-miss” masonry to create a distinctive identity deeply rooted in its context.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Qalandiya: the Green Historic Maze - Qalandiya, Palestinian Territory | RIWAQ – CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION

In Qalandiya, in the Palestinian Territories, Riwaq – Centre for Architectural Conservation revitalizes a historic village through incremental restorations and direct community engagement. The jury commended the project for its thoughtful approach to heritage conservation, acknowledging its high level of sensitivity to complex social and political contexts, as well as its emphasis on knowledge generation and sharing.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Qalandiya: the Green Historic Maze - Qalandiya, Palestinian Territory | RIWAQ – CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

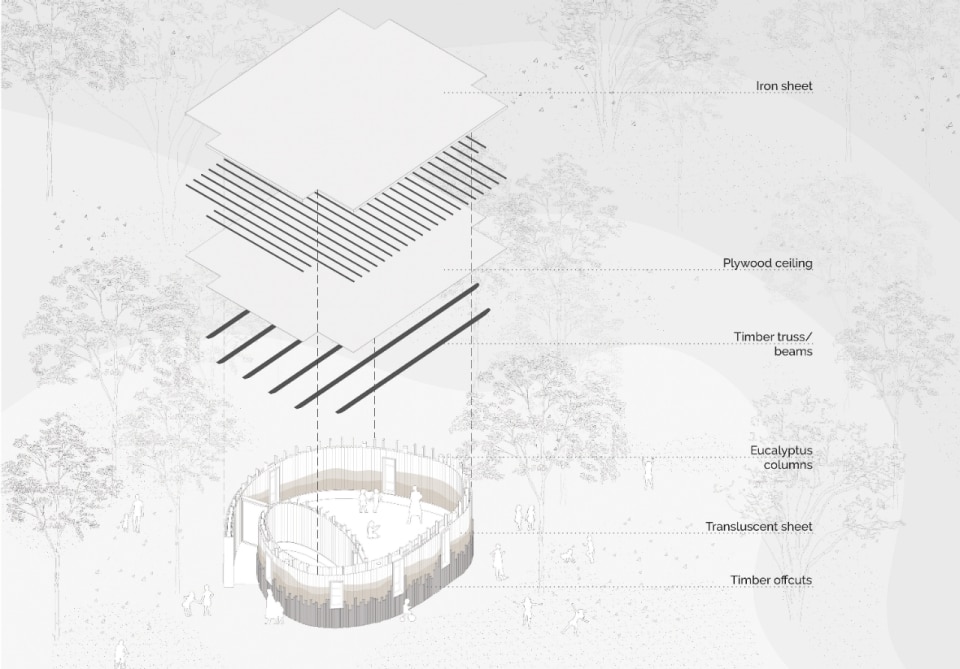

Waldorf School - Nairobi, Kenya | URKO SÁNCHEZ ARCHITECTS

In Nairobi, the Waldorf School by Urko Sánchez Architects is set within a protected forest: a temporary, demountable structure built with local earth and timber, promoting the value of impermanence and connection with nature.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Zando Central Market - Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | THINK TANK ARCHITECTURE

In Kinshasa, the Zando Central Market by Think Tank Architecture revitalizes the historic city market with a minimalist, tactile language: concrete and terracotta bricks define ventilated and luminous spaces, restoring dignity and safety to the twenty thousand vendors who animate it daily.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Zando Central Market - Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | THINK TANK ARCHITECTURE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre - Winnipeg, MB, Canada | STANTEC ARCHITECTURE

The Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre in Winnipeg is a low-impact timber and concrete Passive House pavilion that celebrates the renaturalization of a former quarry and the knowledge of Indigenous communities. The project integrates ecological restoration through native prairie landscaping, bio-swales, and stormwater management, while also incorporating Indigenous design elements developed in collaboration with local elders, reflecting traditional knowledge and community values.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre - Winnipeg, MB, Canada | STANTEC ARCHITECTURE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Lawson Centre for Sustainability - Toronto, ON, Canada | MECANOO ARCHITECTEN

In Toronto, the Lawson Centre for Sustainability by Mecanoo Architecten integrates student residences, learning spaces, and productive gardens. The jury remarked: “For sustainable urban living that will inspire future generations of students to advance their learning here beyond the campus.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Lawson Centre for Sustainability - Toronto, ON, Canada | MECANOO ARCHITECTEN

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Moakley Park - Boston, MA, United States | STOSS LANDSCAPE URBANISM

In Boston, the Moakley Park project by Stoss Landscape Urbanism transforms the waterfront into a resilient landscape that protects the city from storm surges while providing new green public spaces.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Moakley Park - Boston, MA, United States | STOSS LANDSCAPE URBANISM

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Portland Intl. Main Terminal - Portland, OR, United States | ZGF

Closing the selection is the Portland International Airport Main Terminal by ZGF, featuring its massive glulam timber roof and a bioclimatic design that drastically reduces embodied carbon.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Gelephu Mindfulness City - Gelephu, Bhutan | BIG – BJARKE INGELS GROUP

In Bhutan, the Gelephu Mindfulness City designed by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group envisions a new spiritual and economic capital built on harmony between people and nature: neighborhoods that follow the natural valleys, local materials, hydropower, and urban farming come together in a holistic – and seemingly replicable – urban model.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Gelephu Mindfulness City - Gelephu, Bhutan | BIG – BJARKE INGELS GROUP

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Healing Through Design - Bengaluru, India | THE AGAMI PROJECT / A THRESHOLD

In Bangalore, the Healing Through Design project by The Agami Project and A Threshold draws inspiration from the Japanese art of kintsugi: reclaimed materials and construction waste are transformed into a health and training center that restores dignity and beauty to urban fragilities.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Healing Through Design - Bengaluru, India | THE AGAMI PROJECT / A THRESHOLD

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Old Dhaka Central Jail Conservation - Dhaka, Bangladesh | FORM.3 ARCHITECTS

In Bangladesh, the conservation of Dhaka’s former Central Jail by FORM.3 Architects places memory at the heart of urban life, transforming a symbol of confinement into a public park, museum, and community space. According to the jury, the project “retains and rehabilitates historic structures, adds appropriately scaled new buildings, and even integrates a needed public road through the site to ease traffic, all without losing sight of the community’s needs.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Old Dhaka Central Jail Conservation - Dhaka, Bangladesh | FORM.3 ARCHITECTS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Pingshan River Blueway Landscape - Shenzhen, China | SASAKI ASSOCIATES, INC

In Shenzhen, the Pingshan River Blueway Landscape by Sasaki Associates revitalizes 40 kilometers of riverbanks with a “holistic vision,” combining biodiversity, natural drainage, and accessible public spaces within a large urban ecological corridor.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Pingshan River Blueway Landscape - Shenzhen, China | SASAKI ASSOCIATES, INC

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Art-Tek Tulltorja - Pristina, Kosovo | RAFI SEGAL A+U, OFFICE OF URBAN DRAFTERS, ORG PERMANENT MODERNITY, STUDIO REV

In Pristina, Kosovo, Art-Tek Tulltorja (by Rafi Segal A+U, Office of Urban Drafters, ORG Permanent Modernity, Studio REV) transforms a former brick factory into an art and technology center, turning a site of industrial memory into a hub for community innovation. The jury noted that in post-conflict Kosovo, this project – which embraces environmental remediation, cultural programming, and economic development – could have a profound impact.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Art-Tek Tulltorja - Pristina, Kosovo | RAFI SEGAL A+U, OFFICE OF URBAN DRAFTERS, ORG PERMANENT MODERNITY, STUDIO REV

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

School in Gaüses - Girona, Spain | TED'A ARQUITECTES

In Spain, the School in Gaüses by Ted’A Arquitectes reimagines the rural school as an ecological micro-campus, built with local rammed earth, wood, and cork, where learning extends into the natural environment.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Crafts College - Herning, Denmark | DORTE MANDRUP

In Denmark, The Crafts College by Dorte Mandrup is a campus that combines school, housing, and workshops for construction techniques. The jury particularly praised its social mission: “Using design to champion under-prioritized craftspeople, the project affirms that beautiful, context-rooted architecture can instill pride, know-how, and excellence in its users.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Southern River Parks - Madrid, Spain | ALDAYJOVER ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE

The second Spanish project awarded is The Southern River Parks by Aldayjover Architecture and Landscape, which redesigned a thousand hectares along Madrid’s Manzanares and Gavia rivers, creating a green system that counters desertification and promotes urban agriculture.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

The Southern River Parks - Madrid, Spain | ALDAYJOVER ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing - Asunción, Paraguay | MOS ARCHITECTS & ADAMO FAIDEN

In Asunción, MOS Architects & Adamo Faiden tackle housing vulnerability through a participatory approach: Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing consists of modular homes, local materials, and shared public spaces that help mend the social fabric.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Barrio Chacarita Alta Housing - Asunción, Paraguay | MOS ARCHITECTS & ADAMO FAIDEN

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Return of the Lost Gardens - Medellín, Colombia | CONNATURAL

In Medellín, the Return of the Lost Gardens project by Connatural “deconstructs” a university building to uncover a hidden stream, creating a teaching garden and a biodiversity laboratory.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Return of the Lost Gardens - Medellín, Colombia | CONNATURAL

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Schools for Flood-Prone Areas - Porto Alegre, Brazil | ANDRADE MORETTIN ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS, SAUERMARTINS

In Porto Alegre, Brazil, Schools for Flood-Prone Areas by Andrade Morettin Arquitetos Associados and Sauermartins raise classrooms and transform rooftops into community shelters, offering a replicable model for flood-prone regions.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Schools for Flood-Prone Areas - Porto Alegre, Brazil | ANDRADE MORETTIN ARQUITETOS ASSOCIADOS, SAUERMARTINS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II - São Paulo, Brazil | UNA ARQUITETOS

The Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II in São Paulo transforms a degraded area into an inclusive civic center, hosting spaces for sports, education, and culture in the heart of the metropolis. The Jury highlighted the project’s ability to insert meaningful public space “where there was apparently no way to do something,” significantly improving the quality of life in São Paulo’s historic center.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Sesc Parque Dom Pedro II - São Paulo, Brazil | UNA ARQUITETOS

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Brookside Secondary School - Asaba, Nigeria | STUDIO CONTRA

Many of this year’s awarded projects are schools. In Nigeria, Brookside Secondary School by Studio Contra combines climate-responsive architecture, local materials, and traditional techniques: built with locally made clay bricks, the campus employs the traditional barrel vault, arches, and “hit-and-miss” masonry to create a distinctive identity deeply rooted in its context.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Qalandiya: the Green Historic Maze - Qalandiya, Palestinian Territory | RIWAQ – CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION

In Qalandiya, in the Palestinian Territories, Riwaq – Centre for Architectural Conservation revitalizes a historic village through incremental restorations and direct community engagement. The jury commended the project for its thoughtful approach to heritage conservation, acknowledging its high level of sensitivity to complex social and political contexts, as well as its emphasis on knowledge generation and sharing.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Qalandiya: the Green Historic Maze - Qalandiya, Palestinian Territory | RIWAQ – CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Waldorf School - Nairobi, Kenya | URKO SÁNCHEZ ARCHITECTS

In Nairobi, the Waldorf School by Urko Sánchez Architects is set within a protected forest: a temporary, demountable structure built with local earth and timber, promoting the value of impermanence and connection with nature.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Zando Central Market - Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | THINK TANK ARCHITECTURE

In Kinshasa, the Zando Central Market by Think Tank Architecture revitalizes the historic city market with a minimalist, tactile language: concrete and terracotta bricks define ventilated and luminous spaces, restoring dignity and safety to the twenty thousand vendors who animate it daily.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Zando Central Market - Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | THINK TANK ARCHITECTURE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre - Winnipeg, MB, Canada | STANTEC ARCHITECTURE

The Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre in Winnipeg is a low-impact timber and concrete Passive House pavilion that celebrates the renaturalization of a former quarry and the knowledge of Indigenous communities. The project integrates ecological restoration through native prairie landscaping, bio-swales, and stormwater management, while also incorporating Indigenous design elements developed in collaboration with local elders, reflecting traditional knowledge and community values.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Buffalo Crossing Visitor Centre - Winnipeg, MB, Canada | STANTEC ARCHITECTURE

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Lawson Centre for Sustainability - Toronto, ON, Canada | MECANOO ARCHITECTEN

In Toronto, the Lawson Centre for Sustainability by Mecanoo Architecten integrates student residences, learning spaces, and productive gardens. The jury remarked: “For sustainable urban living that will inspire future generations of students to advance their learning here beyond the campus.”

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Lawson Centre for Sustainability - Toronto, ON, Canada | MECANOO ARCHITECTEN

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Moakley Park - Boston, MA, United States | STOSS LANDSCAPE URBANISM

In Boston, the Moakley Park project by Stoss Landscape Urbanism transforms the waterfront into a resilient landscape that protects the city from storm surges while providing new green public spaces.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Moakley Park - Boston, MA, United States | STOSS LANDSCAPE URBANISM

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

Portland Intl. Main Terminal - Portland, OR, United States | ZGF

Closing the selection is the Portland International Airport Main Terminal by ZGF, featuring its massive glulam timber roof and a bioclimatic design that drastically reduces embodied carbon.

Courtesy Holcim Foundation

And then there is that word: sustainable. A mantra these days. Sustainable, sustainable, sustainable — repeated so often it seems to have dissolved into air.

But what does sustainable really mean, this keyword that new projects wear like the trendiest handbag? “If sustainability becomes a trend, then it disappears,” says French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh, the only architect featured in the Time list of the 100 most influential people of 2025, and chair of the Africa & Middle East jury.

It may not be a trend, but it is certainly a tendency — especially in Europe and among younger offices — observes Norwegian architect Kjetil Thorsen, cofounder of Snøhetta and chair of the European jury. He expands the definition beyond the ecological paradigm: “Sustainability is social before everything else,” and “If people don’t want to use a space, it cannot be sustainable.”

You build a school, but you are actually building a community.

Sara Navrady and Rodrigo Louro, Mecanoo

What does exactly “sustainable architecture” mean?

For Mecanoo — the Dutch studio led by Francine Houben and represented here by designers Sara Navrady and Rodrigo Louro, who worked on the Trinity College project in Toronto, exploring the relationship between architecture, community and harsh North American climates, with a strong focus on urban agriculture — sustainability means building places where people can see themselves reflected. “You build a school, but you are actually building a community.”

Designing something that is meant to last — “If it lasts long, then it’s about sustainability”: with this, Chinese architect Ma Yansong — Domus Guest Editor 2026 and member of the Asia jury — introduces the theme of time. For him, architecture unfolds along the arc of history: “Architecture is about time, it’s about the memory, it’s about the future, about the imagination.”

You cannot achieve sustainability through design alone… The projects that work are the ones where you build coalitions.

Jeanne Gang, Studio Gang

American architect Jeanne Gang, founding partner of Studio Gang and chair of the North America jury, brings the conversation back to legislation. “You cannot achieve sustainability through design alone,” she notes, lamenting the absence in the U.S. of a regulatory framework comparable to Europe’s. Sustainability becomes a form of coalition-building: “The projects that work are the ones where you build coalitions.”

A global map without a single truth

Sustainability costs money — and is often the first thing cut when budgets shrink. The Awards, by supporting real projects with real funding, help safeguard their sustainable value. At the same time, selecting five projects across five world regions sketches a global map of sustainability — yet no single definition emerges. As Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in his Philosophical Investigations, “the meaning of a word is its use in the language.” And what this global mapping shows — as Danish architect Dorte Mandrup notes, participating with her Crafts College in Herning — is that every region has its own story. “How can you compare a Scandinavian project to a Nigerian project? You can’t.” “Impact means different things in different places.”

Designing something that is meant to last — if it lasts long, then it’s about sustainability.

Ma Yansong, Mad Architects, guest editor Domus 2026

Thus the Asia winner, in Dhaka (Old Dhaka Central Jail Transformation, Form.3 Architects), may share certain themes with the European winner — while the project for Africa & Middle East (Qalandiya: The Green Historic Maze, Riwaq) is entirely unique. Meanwhile, Boston’s flood-resilient park (Moakley Park Vision Plan, Stoss Landscape Urbanism) — though seemingly the most “classic” sustainable project — is perhaps the one that best stitches together the guarded optimism of the Awards with the urgency that permeated the Forum: the need to intervene before the storm.

The Bhutan paradox

A special case is BIG’s project in Bhutan — a proposal that, as Ma Yansong notes in an ideal handover from Bjarke Ingels (Domus Guest Editor 2025) to himself (Guest Editor 2026), “really split the jury.” Can designing an entirely new city — complete with an airport — be considered sustainable in a country with a fragile landscape and where air travel is the only connection to the outside world? The paradox is real: air travel is the least sustainable mode of mobility, yet it is the only one that prevents Bhutan from being isolated.

How can you compare a Scandinavian project to a Nigerian project? You can’t. Impact means different things in different places.

Dorte Mandrup

And this is where the project becomes compelling. As Giulia Frittoli and Frederik Lyng explain, BIG is not imagining a Western-style capital, but a constellation of settlements that extend from the landscape itself: “Landscape first, architecture second.” For Ma, “A village can have a future” — and this is what shifts the debate. “A project should encourage people to have better hope.” In Bhutan, “future” does not mean

skyscrapers or smart cities, but the possibility for a community to remain alive, for traditions to grow without turning into a museum.

All this because — as Venice teaches us — sustainability is not one precise thing. It is not like Kant’s moral law “within us,” but like the starry sky above our heads: different from region to region, continent to continent. And yet still a sky — still a guiding star. Not to design a better world — that may be too optimistic — but to design a world in which we can survive the increasingly harsh challenges that climate change will bring. Challenges that concern everyone, even those who assume they are safe. The future will be fragile everywhere. Just like Venice — queen of the seas, commercial powerhouse, jewel of the world — now risks being swallowed by the very water that once made it great.

Opening image: Gelephu Mindfulness City - Gelephu, Bhutan | BIG - BJARKE INGELS GROUP