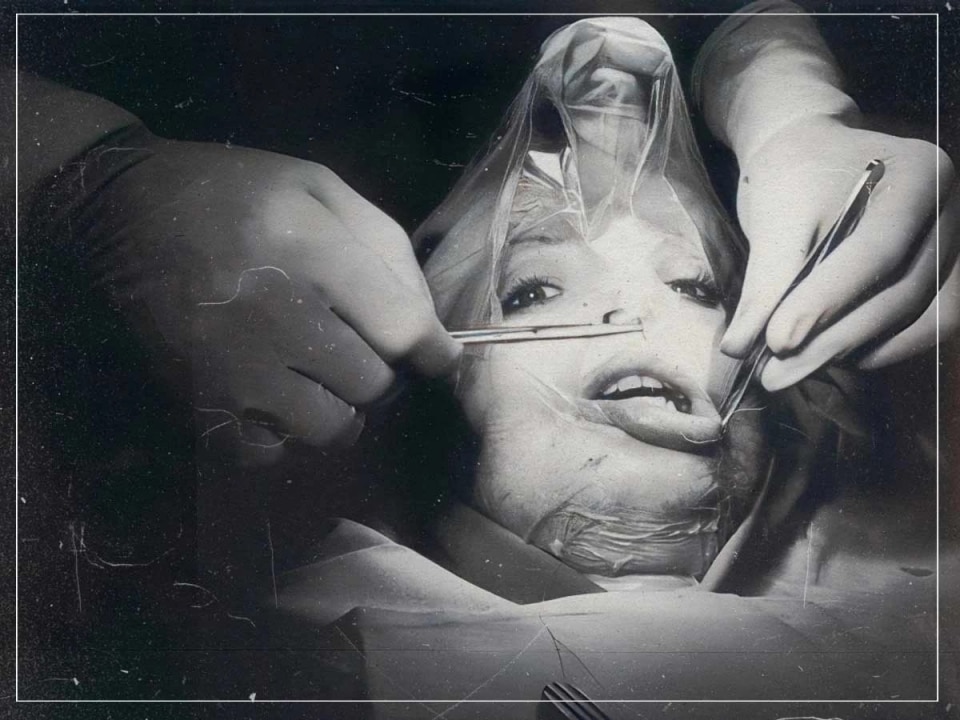

In the 21st century, the face has ceased to be a simple biological given and has become a designed interface. From beauty filters to algorithm-guided procedures, from facial recognition software to “AI-inspired” surgeries widespread in Asia, facial design today redraws the boundaries between body, identity and project. The exhibition “Face Value” at MoMA (2026) will reconstruct the analog genealogy of this manipulation, showing how promotional portraits produced by film studios were already subjected to radical editing: silhouettes, masking, collage and paint corrected the images of actors, athletes, socialites and politicians. Visual designer and essayist Riccardo Falcinelli has long described the face as “our own invention”: well before the digital age, the public image was already a designed artifact, a vehicle for gender stereotypes and codified aesthetic conventions.

The face as interface

The concept of “design” thus extends to the body itself, and above all to the face, which has become a privileged space of intervention and control, moving toward an almost transhuman condition.

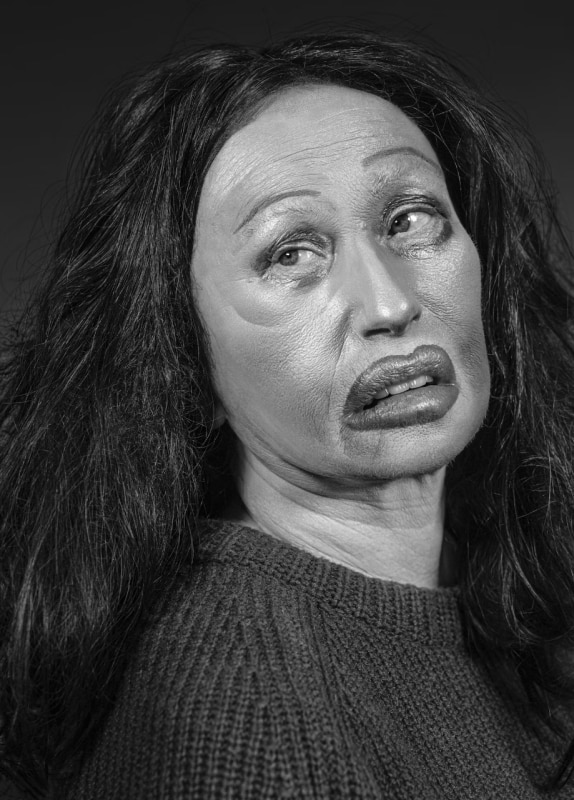

At the same time, art has anticipated and theorized the transformation of the face into an artifact. Orlan, a pioneer of surgical body art, turned the operating room into a studio, transforming cosmetic surgery into a conceptual language. American artist Cindy Sherman has brought her research directly onto Instagram: she thins eyes, lengthens noses, inflates lips through Face Tune, YouCam Makeup and FaceApp, pushing to extremes the distance between image and referent. The selfie becomes a compositional act, a field of metamorphosis that reflects the aesthetics of social media and the culture of the filtered self-portrait. Since 2017, the American artist’s body has thus become the privileged site, both real and virtual, through which to display the use of editing to shape makeup, masking and transformation.

The exhibition “Bodydrift – Anatomies of the Future” (Design Museum Den Bosch, 2020) also explored the fusion between human and machine, focusing on the design of the self. In her “Biometric Mirror”, Lucy McRae invites the viewer to look at themselves in the mirror: what appears is not a reflection, but an idealized face generated by algorithms. A simulation of the self that foreshadows the advent of a computational aesthetic already theorized by Lev Manovich: a “media design” in which algorithms, machine learning and facial recognition automate the transformation of identity. The face, traditionally a symbol of subjectivity, thus also becomes a manipulable object, a data node, an interface that fuses the human and the technological.

The collective project of the face

This transformation takes on a particular radicality in China and South Korea, where cosmetic surgery operates according to almost industrial logics. Here, the face is treated as a collective project: the aesthetic canon is not an individual ideal but a social device, a professional and competitive investment. In her report “About Face” for The New Yorker, Patricia Marx describes a Seoul in which appearance is a job requirement rather than a narcissistic indulgence. Collectivist cultures help explain the desire “to resemble one another,” both in the similitas and the simultas described by philosopher Giorgio Agamben: not only to look like others, but to coincide with a shared model, to adhere to a collective face rather than an individual identity.

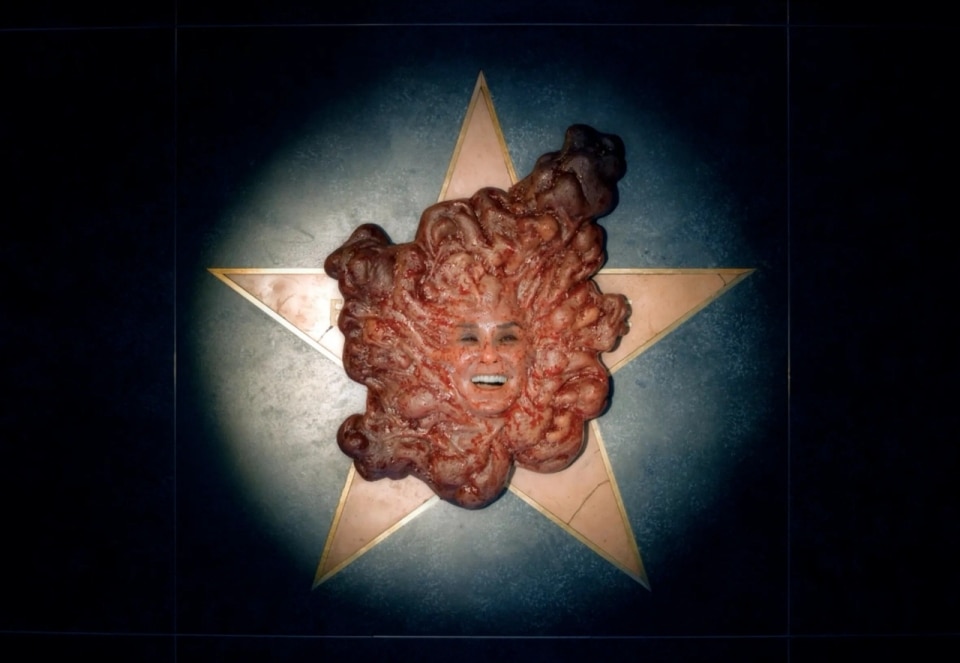

Alongside this dynamic is what writer Jia Tolentino, also in The New Yorker, defined as “The Age of Instagram Face” (2019): a fashionable face composed of an unsettling mix of ethnic traits and digital aesthetic stereotypes, a “single cybernetic look” generated by the intertwining of filters, FaceTune and surgery, flattening differences and turning injectables into a choice as easy as changing a haircut. Meanwhile, the frontiers of K-Beauty—from PDRN, a polymer of DNA fragments mainly derived from salmon with anti-aging effects, to extracts from the leaves of Houttuynia cordata (anti-inflammatory and antioxidant)—show how the search for harmony migrates from Renaissance proportions to biometric and molecular parameters.

Between post-operative videos, smoothed epidermis, and uniformed aesthetics, the risk is one of increasing alienation from one's own face.

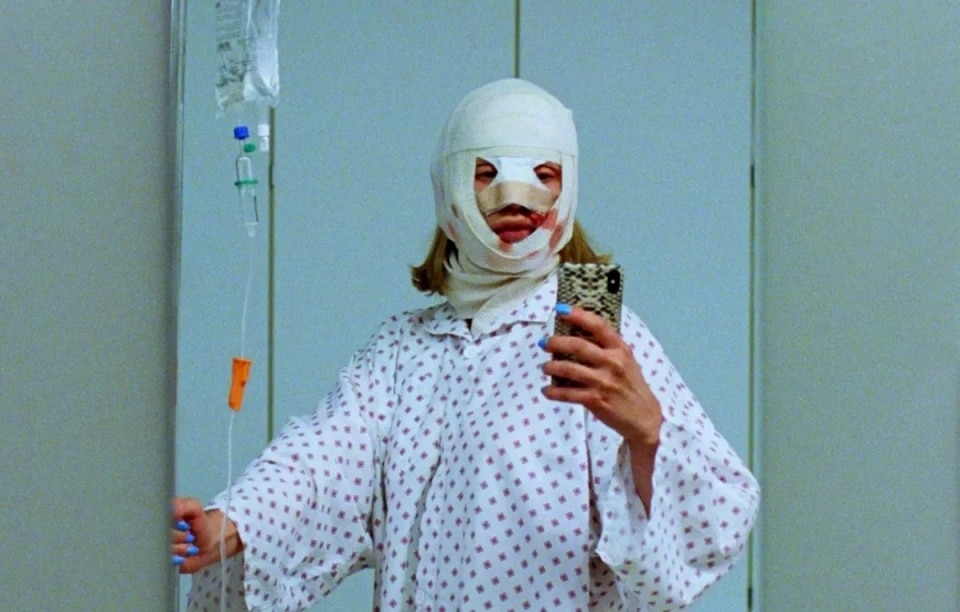

In the West, by contrast, every sign of time is perceived as an individual fault. AR and Instagram filters contribute to blurring the relationship between image and reality: one enters the surgeon’s office with a photo of a celebrity saying “make me like this,” as if the face were a scalable object. Between post-operative videos, smoothed epidermises and standardized aesthetics, the risk is a growing alienation from one’s own face, a distancing from who we actually are toward what we appear to be—a gap that can be, and is meant to be, reduced only through targeted interventions, and therefore through perfectly engineered facial design.

Otherwise, the risk is finding ourselves in front of the mirror like Demi Moore in The Substance, no longer recognizing any correspondence with our social image, to the point of wanting to disfigure the real one.

Young, old, or surgical

Botox is perhaps the most evident symbol of this normalization. Born in 1989 as a medical treatment for strabismus and approved for cosmetic use only in 2002, the product was presented from the outset as natural and essential: “Look like you with fewer lines,” read the first campaign. Yet there is little that is natural about a semi-frozen face designed to prevent aging.

Celebrities, from the Kardashians downward, have turned it into a routine, integrating it into beauty culture as an inevitable and aspirational gesture, almost an extension of personal hygiene. Between street-facing botox bars, flirtatious neon signs and walk-in treatments, injectable aesthetics are fully de-stigmatized. In this scenario, Byung-Chul Han reads digital self-exposure as part of neoliberal “psychopolitics”: in the attempt to become an “entrepreneur of the self,” the individual voluntarily and enthusiastically exploits themselves, transforming the self into a work of art to be displayed and optimized for the system, becoming—through the smartphone—an “info-thing,” self-surveilled and self-exploited in the continuous optimization of the self.

The face, traditionally a symbol of subjectivity, has become a manipulable object, a data node, an interface that merges human and technological.

Films such as Sick of Myself have pushed the discourse onto a further plane, extreme and almost opposite, yet driven by the same underlying obsession with attention and social media. Here the protagonist Signe, jealous of the fame of her artist boyfriend, begins to generate a cycle of body horror and self-destruction in order to gain visibility, playing on the idea of “hurting oneself” to become famous.

Even my own personal experience (the fear that when my eyebrows regain mobility, expression lines might form on my forehead) testifies to how deeply this normality is internalized, how aesthetic medicine generates addiction more powerfully than any benzodiazepines on the market, and how the monstrous “anthropological mutation” imagined by Pasolini has exceeded even his darkest predictions. After all, there are not many choices, as Fran Lebowitz stated in her latest interview on Fallon Tonight: “There’s three ways to look. Young, old, or surgical.”

Perhaps all that remains is pure opposition—or at least the awareness that the face today is a territory of design in continuous rewriting: biological, digital, cultural.

Opening image: Cindy Sherman, Untitled #649, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Hauser&Wirth