The story connecting Domus to the shapeshifting Milan-based entity commonly known as Salone del Mobile can be described as a proper love story. And like every proper love story, it can be made of enthusiasms, consonances, dissonances and frequent mutual yelling, but mostly of a long-lasting sharing of a discourse that very soon got wider and wider, crossing the border of the sole realm of furniture to reach out for research, politics, lifestyles and a global dimension originated from a single city.

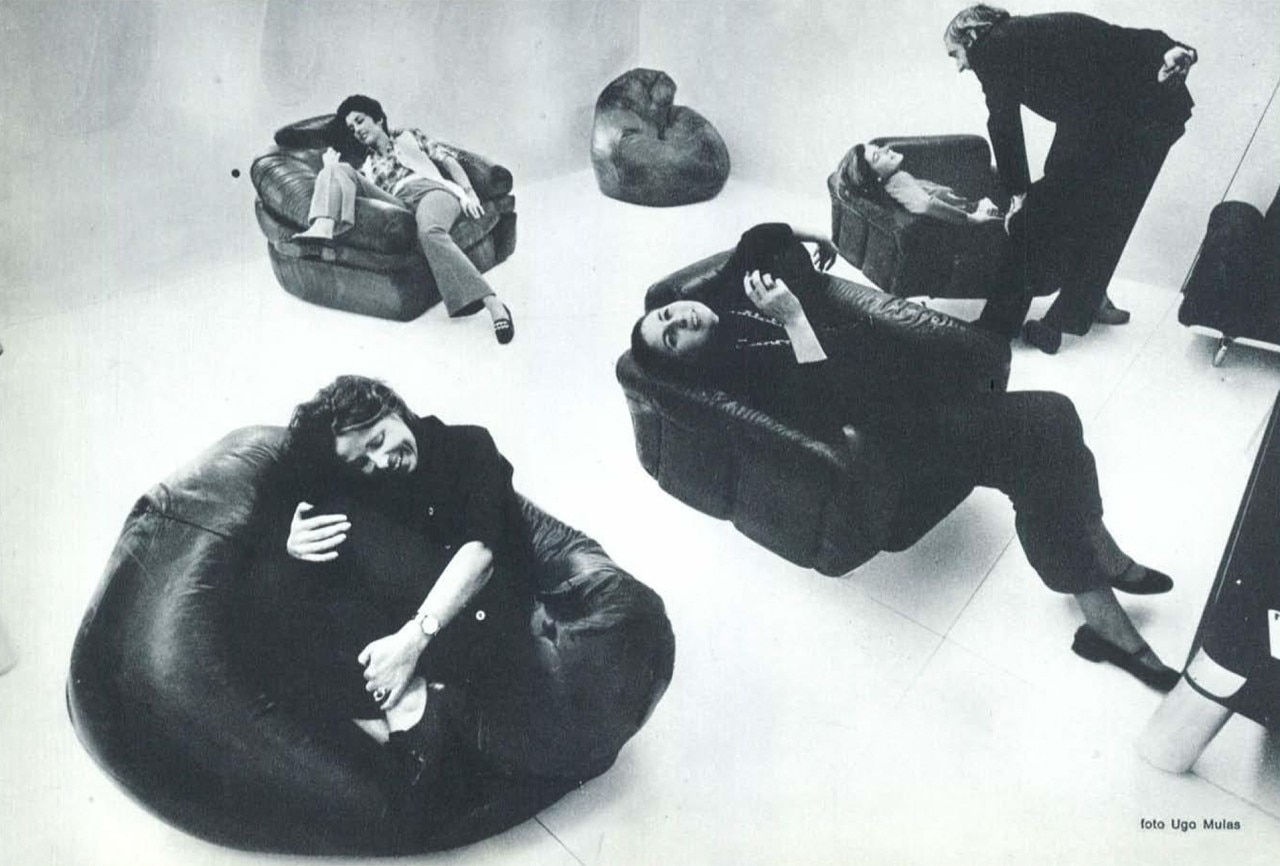

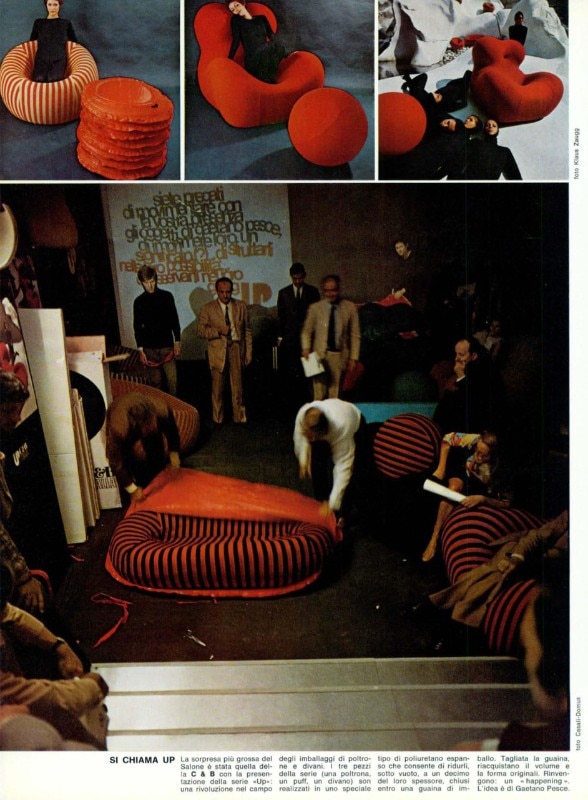

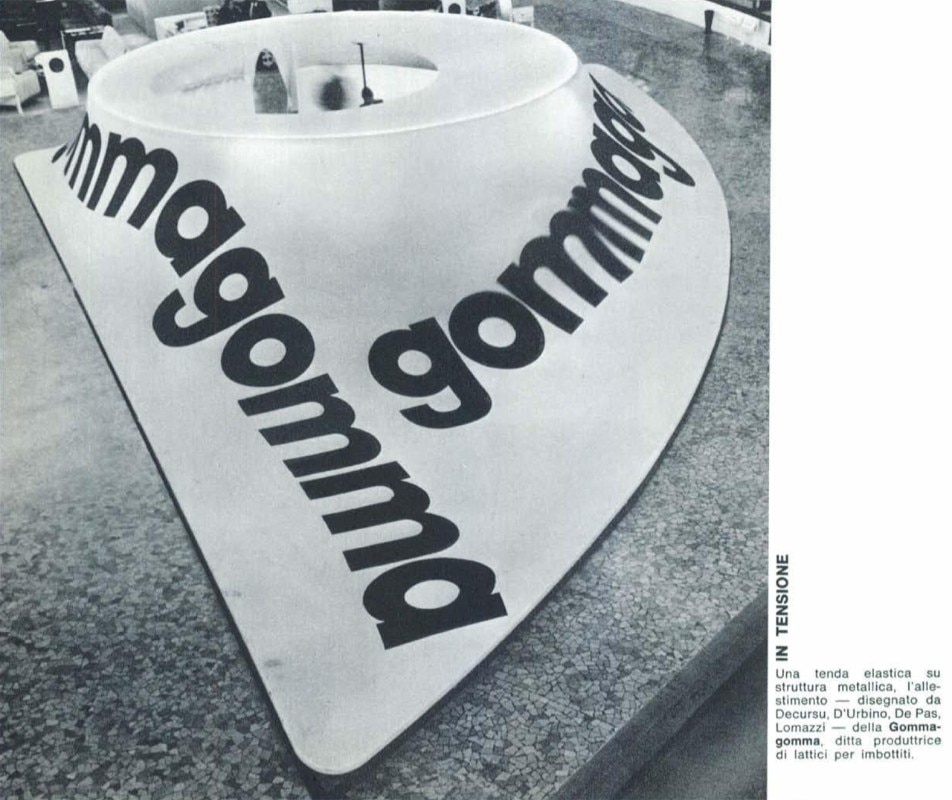

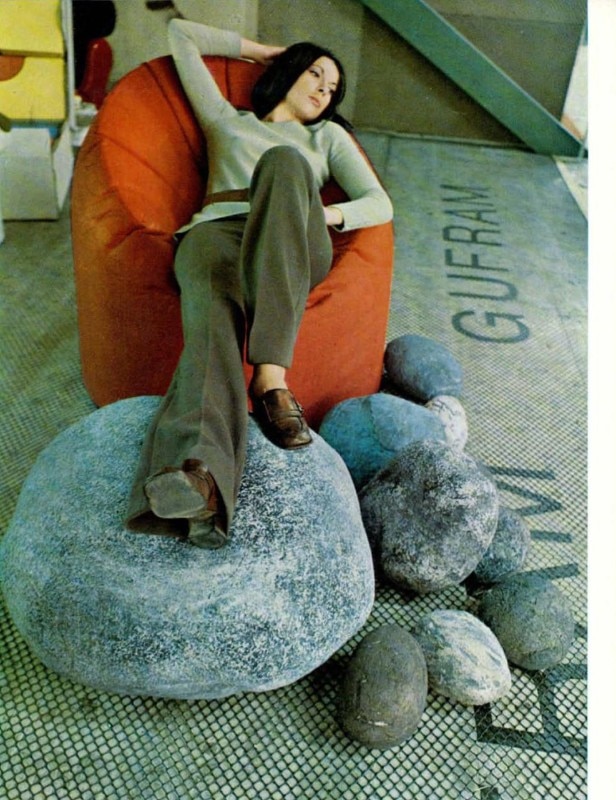

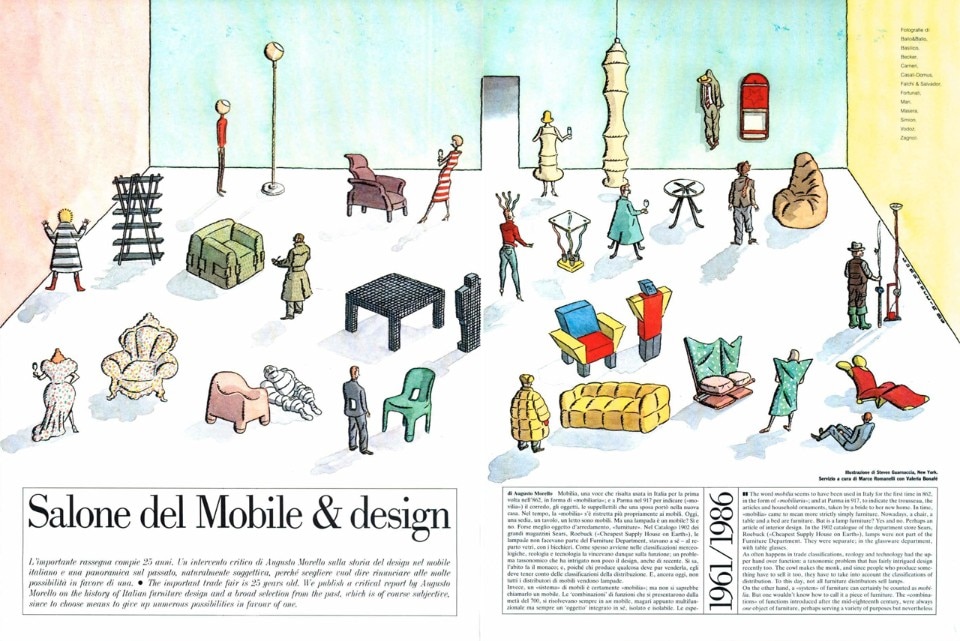

After having spent a first decade as a relevant yet well-behaved commercial event, at the beginning of the 70s the Salone joined the wave of Italian and European radical movements as they were reaching a larger audience. This phenomenon was perfectly represented in the exhibition Italy: the New Domestic Landscape at MoMA in New York, where the objects conceived by Ettore Sottsass, Superstudio, Archizoom and many others were presented by the curator Emilio Ambasz as “shapes that deliberately attempt a commentary upon the roles that these objects are normally expected to play in our society.”

Such inclination to commentary and criticism got more and more evident within the Salone, and it kept on being expressed through the whole decade, but in terms of an increasing contrast between critics and production system, as the words by Ugo La Pietra can witness, describing design system as “an exhausting hunt for novelties through all the operations from the research of innovation onwards, that fatally leads to absurd and harmful forms of competitiveness.” (Domus 577, December 1977). Those years that Jasper Morrison has recently recalled in an intimate account of his early Milanese experiences (Omaggio a Milano, Domus 1050, October 2020) were years when objects and images were basically hunting each other down and merging. Tommaso Trini would describe all this as:

“…the dominance of image over object. This is realism after the creation of white telephones and the slangy contemporaneousness of Antidesign and Folk, Revival, and Pop Art , in which form dominates. Like vitamin enriched food, this type of furniture is enriched by metaphors. There is something for everyone (…) If the Neoclassicals design beautiful objects for irremediably high social classes, the image creators produce for irremediably short terms.”

(Le quattro gambe del design, Domus 601, December 1979)

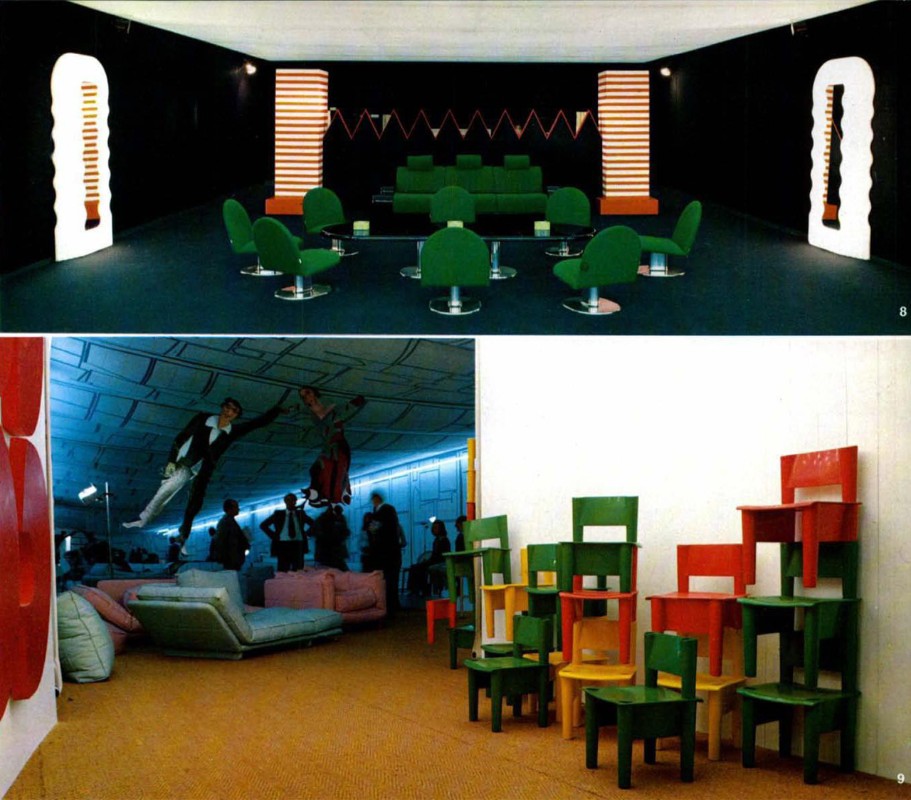

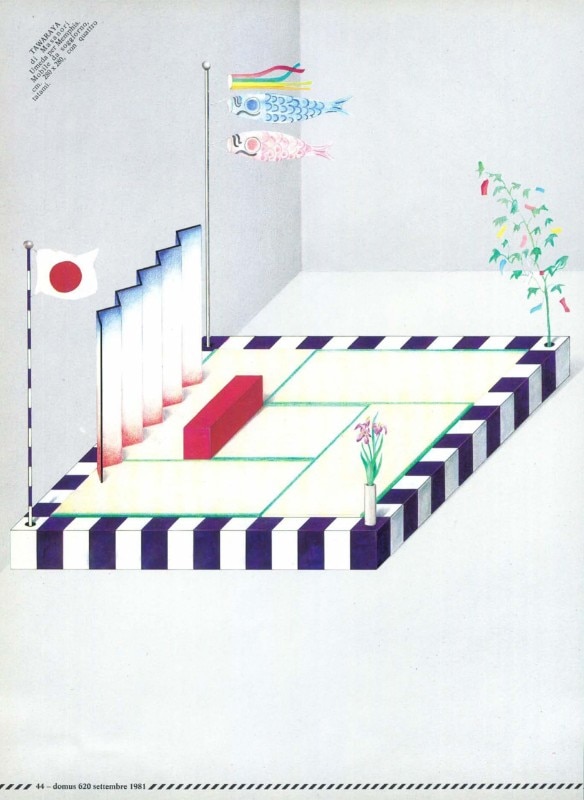

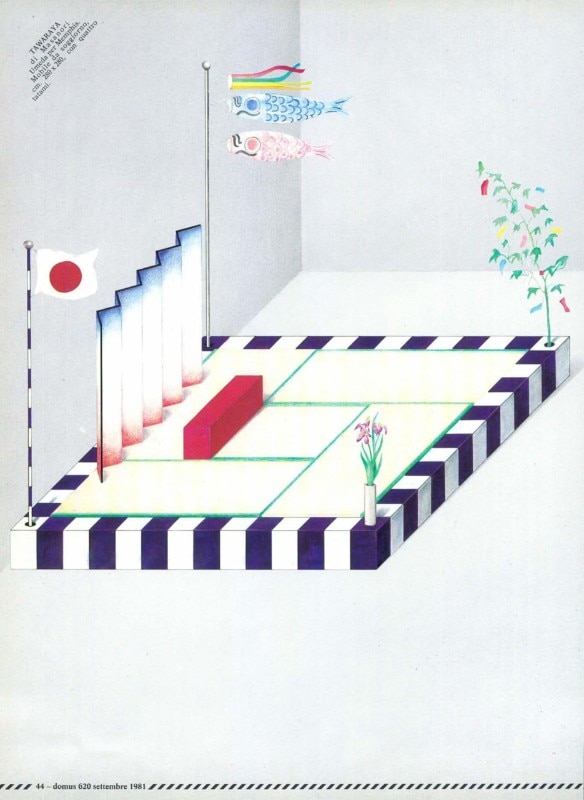

In 1981, such attitude to a critique of objects through objects themselves reached a symbolical climax, as Memphis was born and debarked at the Salone to easily become recognized as “the bomb of the year”.

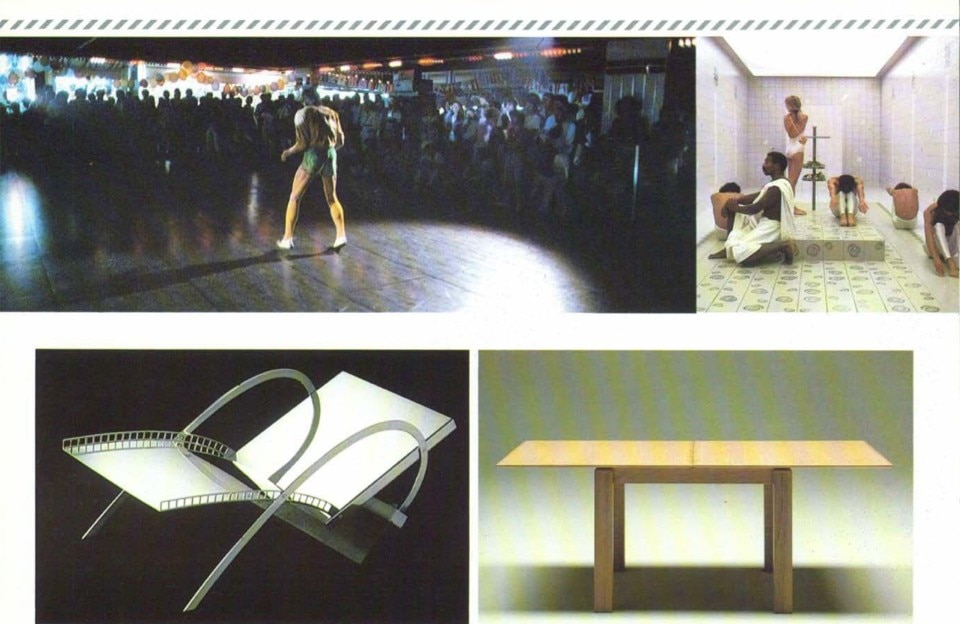

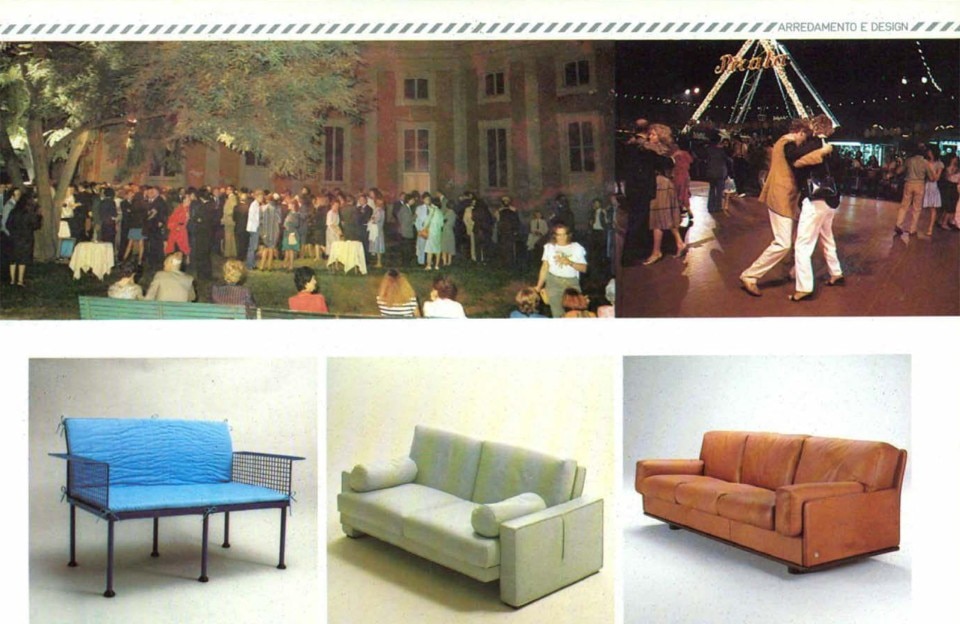

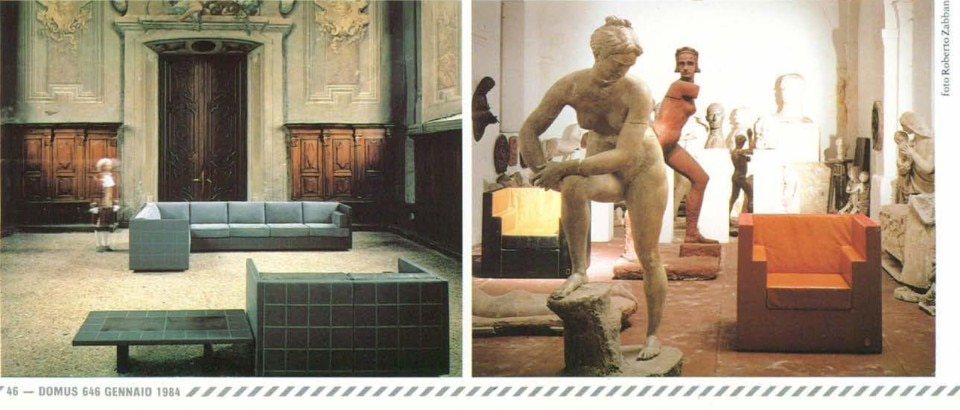

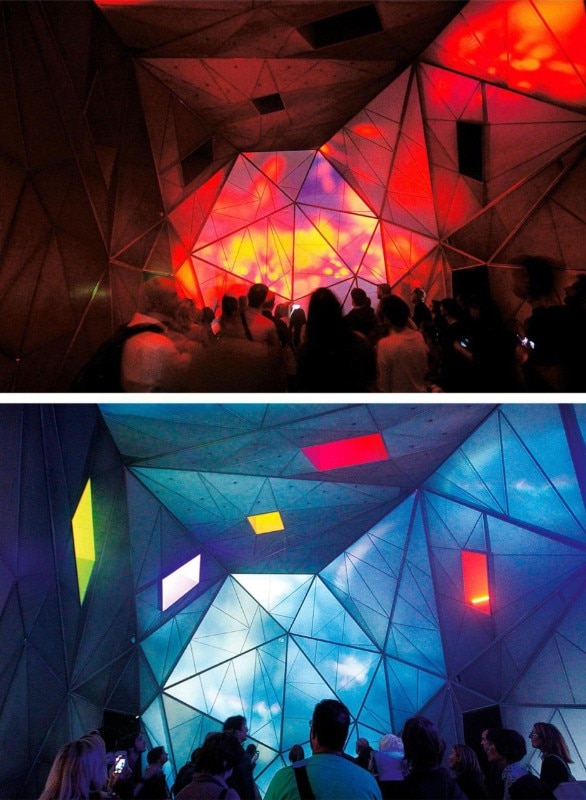

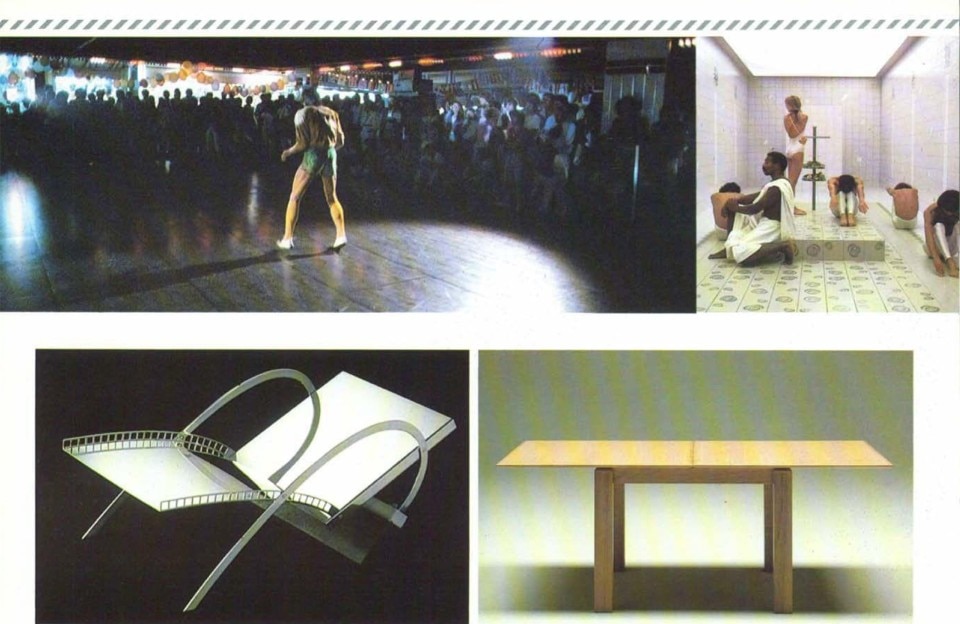

But a further step in evolution was already on the way: together with the transition from late Disco Years to the hedonistic era of Milano da bere (Milano-to-drink, common definition of Early 80s in Milan), the predominance of events was taking over the Salone scene, a triumph of postmodern semiotics transfiguring the well-known device of happenings into a dazzling galaxy of parties, scattered all across the city in the most surprising locations, and quickly gaining a higher relevance than the furniture fair itself. Famous design magazines renting an entire amusement park in the outskirts of Milan, Alcantara launching a design collaboration by gathering a cheerful crowd outside Padiglione di Arte Contemporanea to attend a glass-cased performance, hosted inside the transparent building, and so on. Priorities are swapped: Vanni Pasca would in fact quote Giulio Carlo Argan, the famous Italian art historian, and define such dimension as a progressive process based on mutual chase between objects and their image, as a world where the communication of an object determines its design, where communication itself is design (L’oggetto e l’immagine, Domus 642, September 1983), repeatedly echoed by Ugo La Pietra (Domus 657, January 1985) .

Many postmodern and neo-modern cultist designers theorize on the ephemeral vibrations of the apparent, the transient and temporary event, for a ‘loving’ design in contrast to the old ‘functional’ design

Ugo La Pietra, Domus 657, January 1985

During the following years, the scope of design action and reflection got so wide — spanning across the boundaries of so many disciplines that its own boundaries seemed to disappear — that someone had to take over the role of consciousness of design (this used to be the expression dedicated by Alessandro Mendini to Enzo Mari on Domus, but for sure Mari could not handle all this alone). Critics would therefore take that role, starting from Juli Capella who would become a strict analyst of the Salone during the 90s, asking himself and his colleagues how to cope with the yearly supply of new designs and highlights, as “we always end up being dragged along by that great dictator, the Salone’s annual catwalk which more and more reminds us of the feverish world of fashion.” On another side, Andrea Branzi would stress the civil value of design, the sole force to inspire and organize a proper resistance movement against political status quo in Italy:

“This civilized culture has helped, via domestic things, to implement the modernization that has failed to materialize on the national public scene. Design and fashion are the token of an ‘opposition’ industrial enterprise that lets off its critical steam not in political skirmishing, but in the technical and expressive quality of its products. Further, it puts into worldwide circulation a system of signs of matchless beauty and charisma.”

(Sul Salone del Mobile ‘94, Domus 762, November 1994)

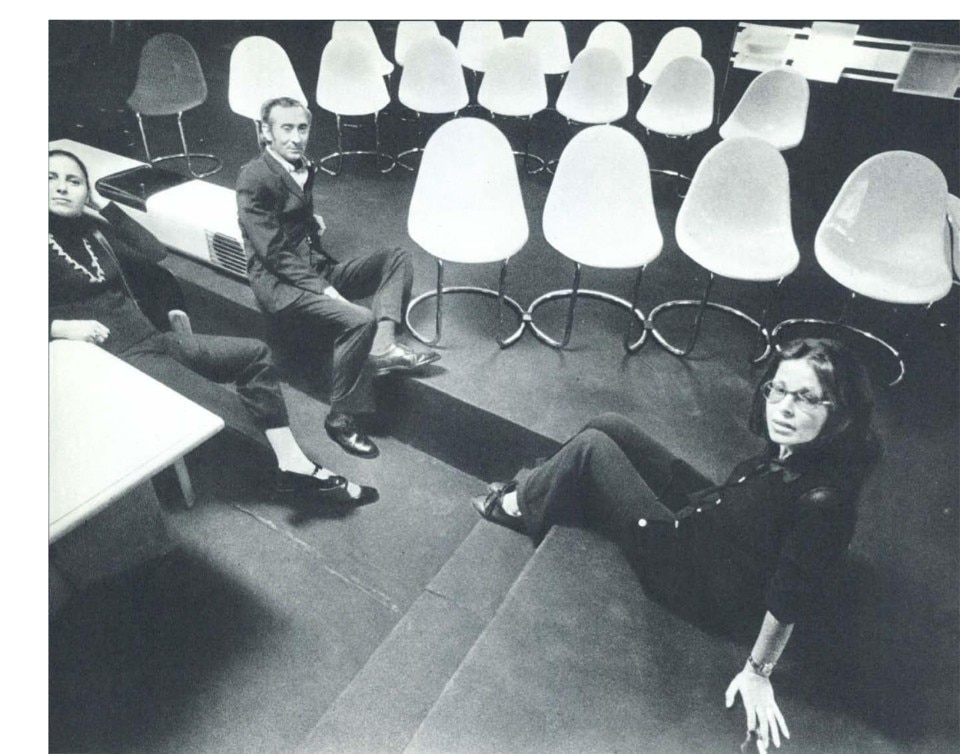

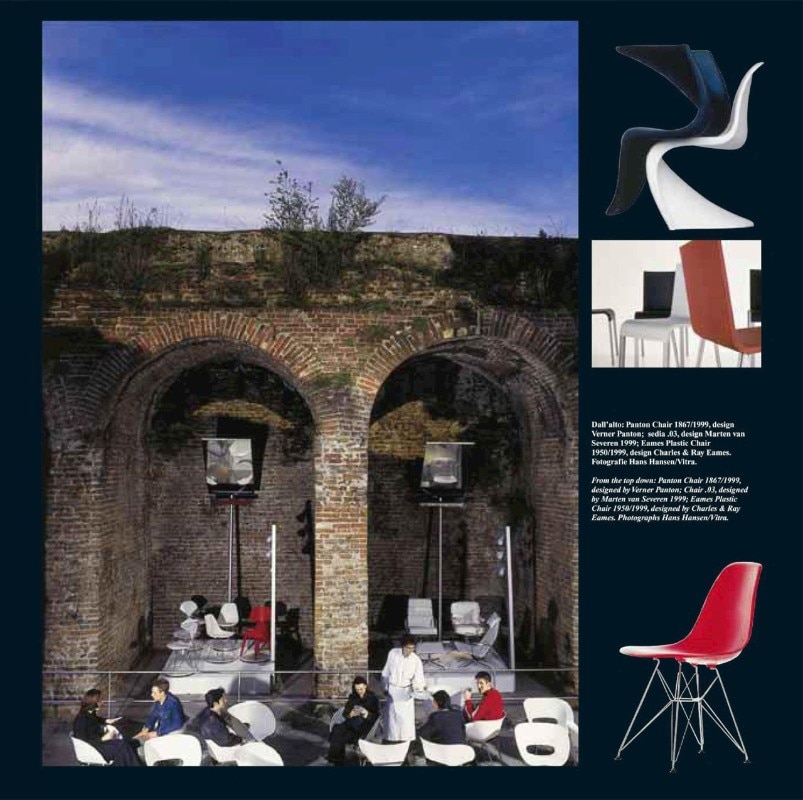

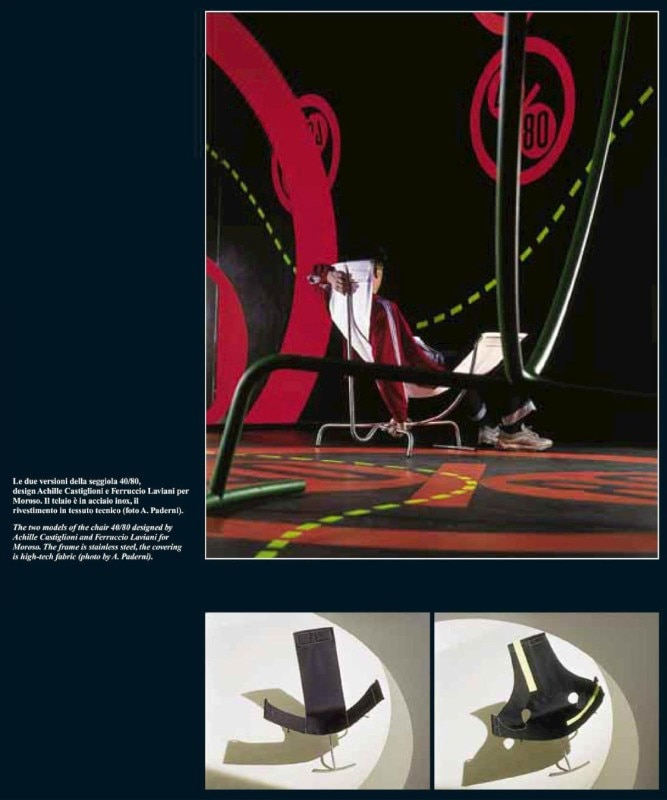

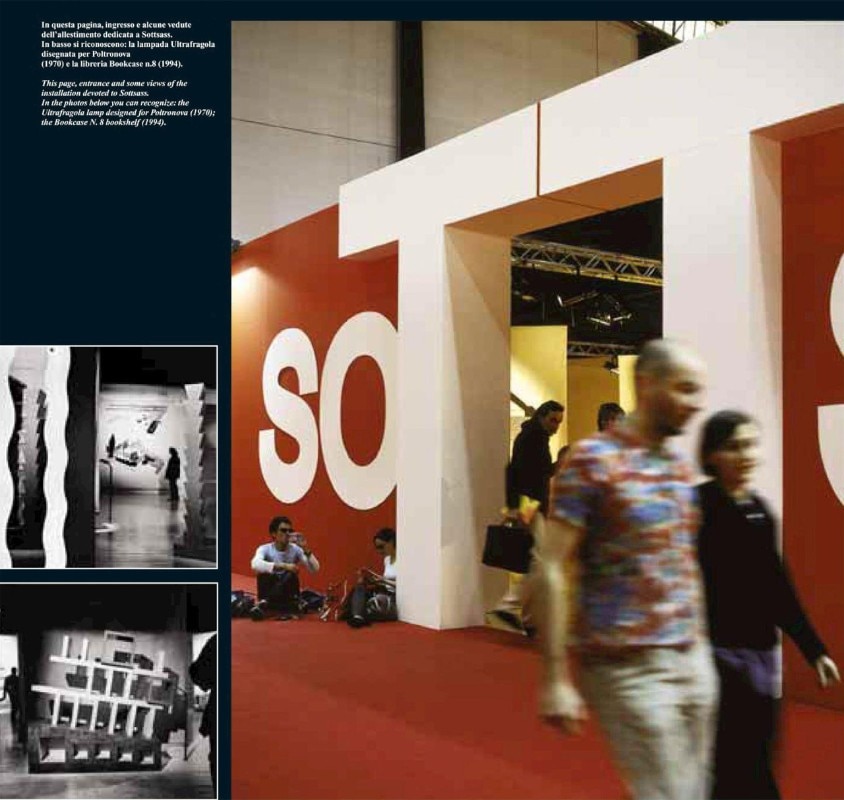

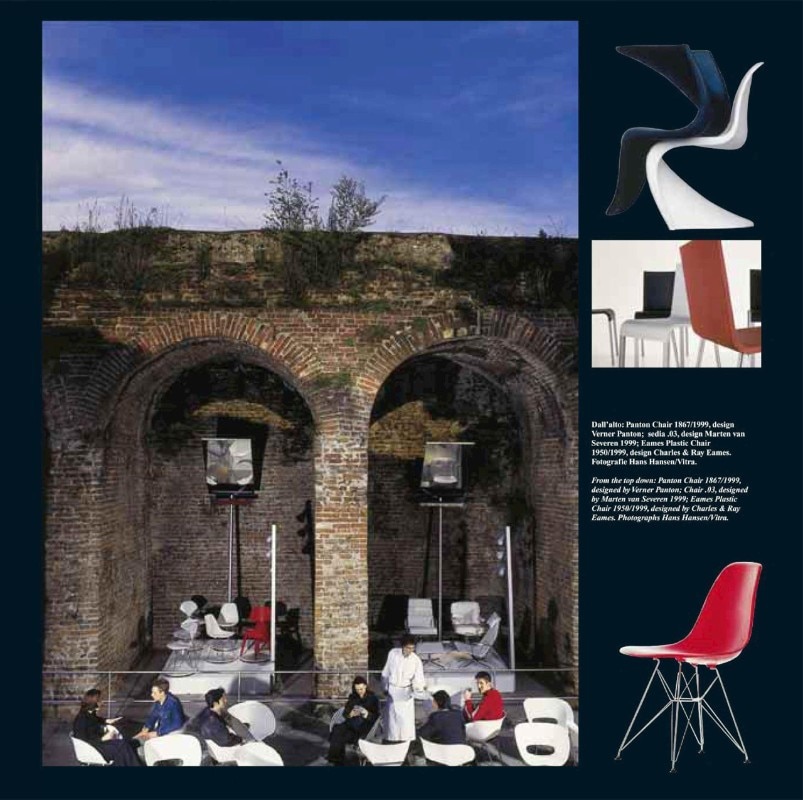

In the meantime, the cultural component was growing stronger within the mission of the Salone and its galaxy: several monographic exhibitions took place during different editions, dedicated to Munari, Aalto, Sottsass, Castiglioni, Colombo and many more.

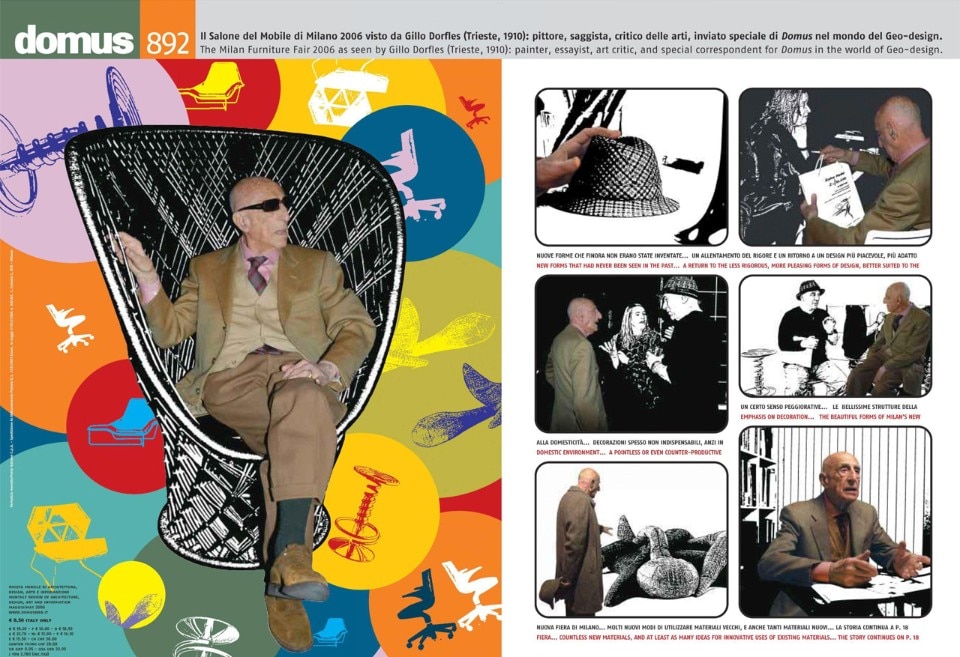

Such role of consciousness of design grew even more full of expectations on critics, as the turn of the millennium got closer ( even though Capella questioned: “What was the big difference between the end of the second millennium design and that of the early third? None at all, for a year in nothing is able to move the gigantic world of furniture”), and as the whole design world was becoming increasingly depending on the authority of big names.

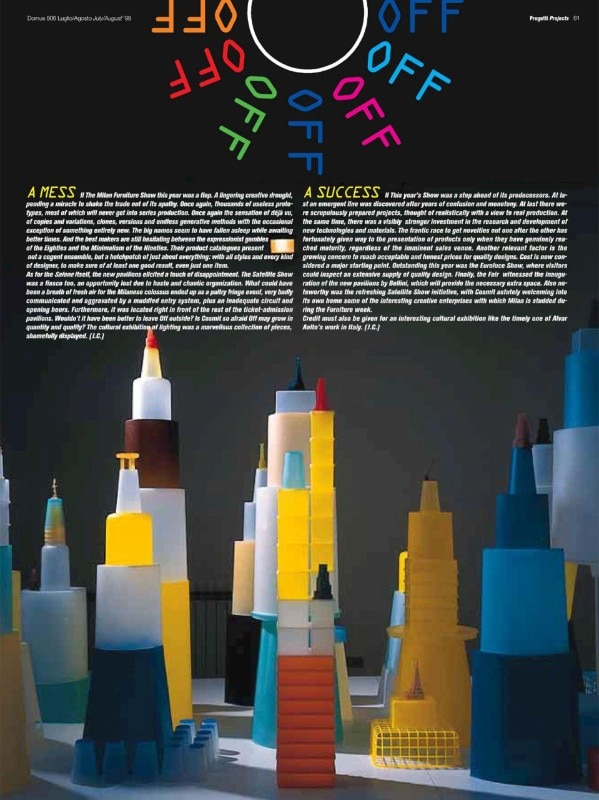

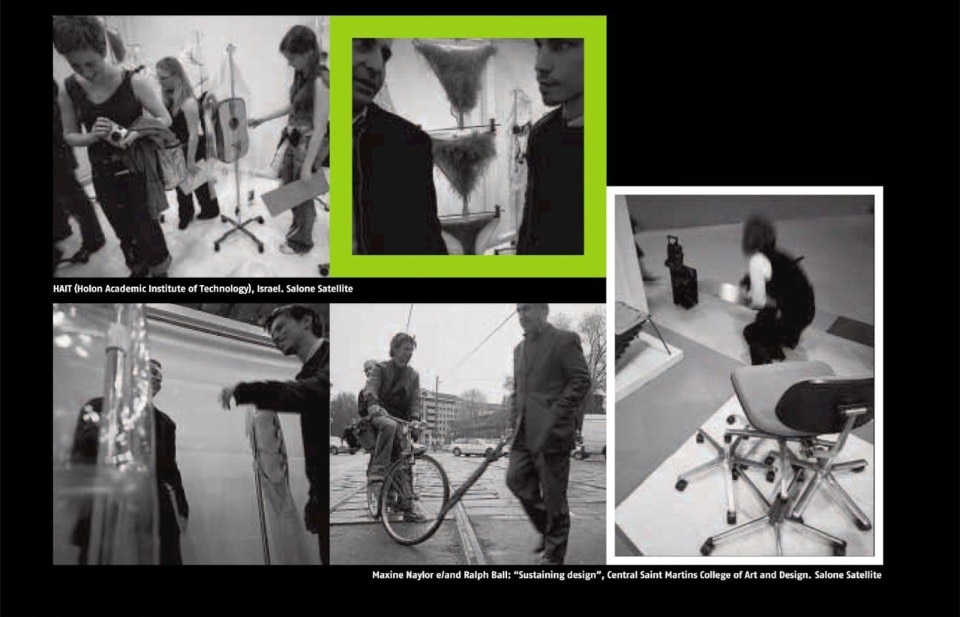

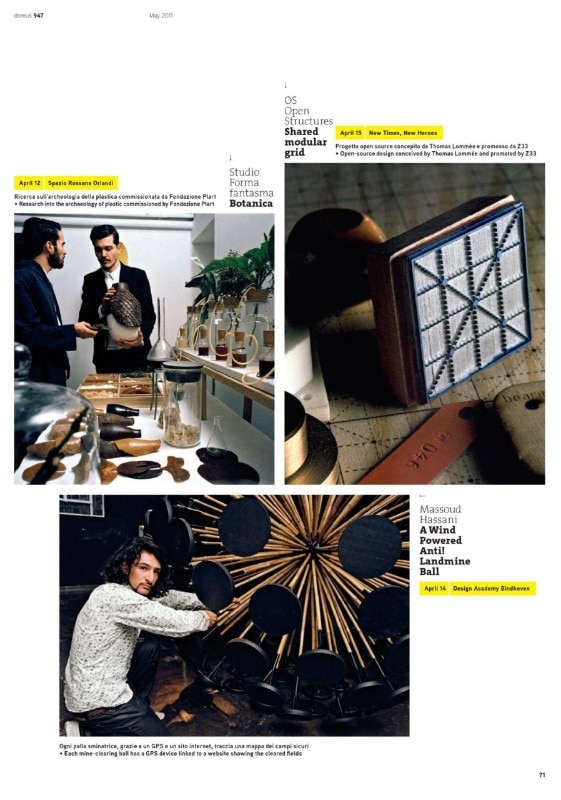

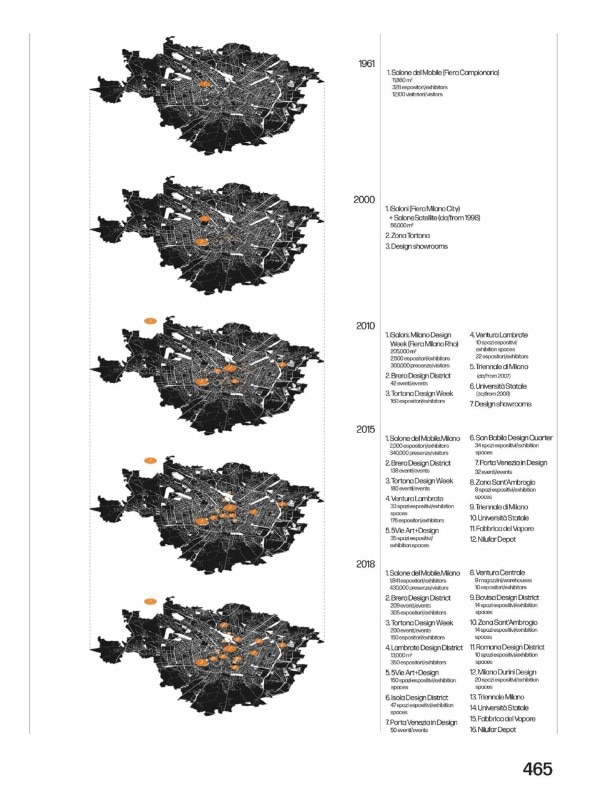

Soon the 9/11 attacks would come and shatter all globalist enthusiasms of the new economy era — and a lot of the carte blanche given to designers’ untamed flair until then (Storie di alberghi, Domus 848, May 2002) — but a new season was starting in any case, the Design Week era as we recently know it, with the Salone main event, the Salone Satellite besides, the Fuorisalone (Salone off) all across the city, and the Stars , the starchitects, the star designers. Names. In providing an account ( a day-by-day account since 2002, provided by a newborn domusweb.it ) of a season of bewilderment for what concerned principles, still packed with influential figures, names, Domus kept searching for a way out: names, again, but both famous and emerging names, all of them to be asked the same question, “where are we going?” Then be them Tokujin Yoshioka bringing us on the border between design and fashion on board of a sheet of paper, or be them the young Joris Laarman riding his bike through the streets of Milan to compose a live selection of highlights from an bustling Fuorisalone (La scelta di Joris, Domus 870, May 2004), their main mission remained to give a bewildered audience the chance to understand their times, to master them as they were starting to do with a relatively new digital dimension.

… where art, design, fashion and all the rest melt into a happy and almost always surprising result… The review of the Fuori Salone 2003 read the other day via Google, continues to go round my head…melt in a happy and surprising result art, design, fashion and all the rest, I have great faith in all the rest. (20-10-03)

Stefano Mirti, Domus 869, April 2003

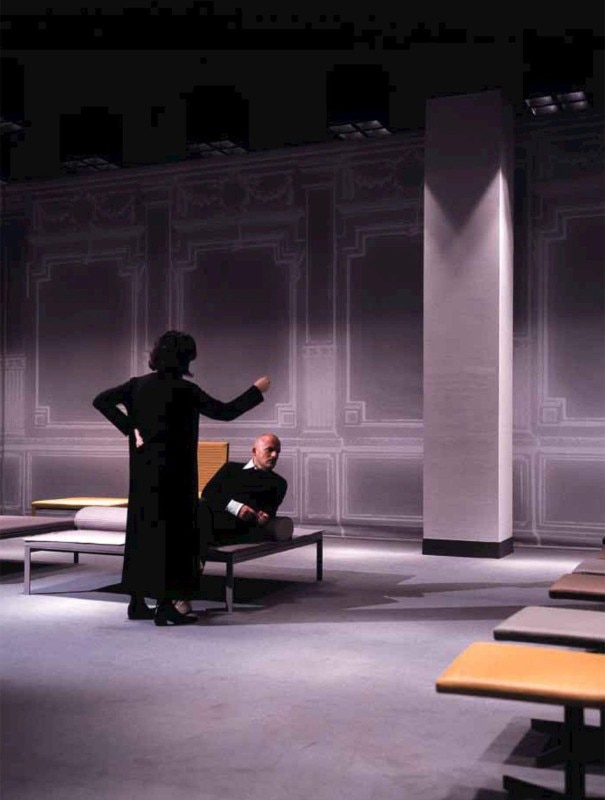

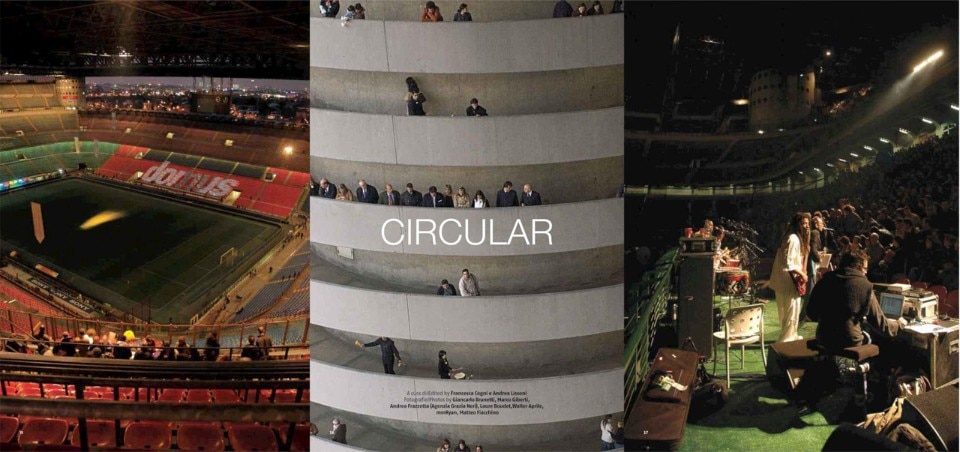

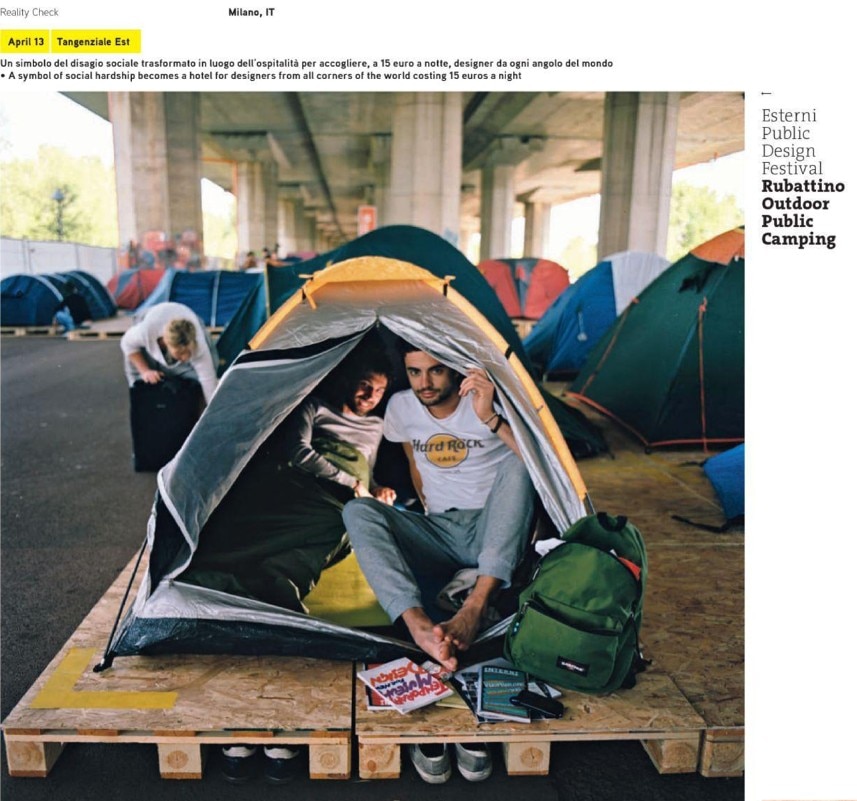

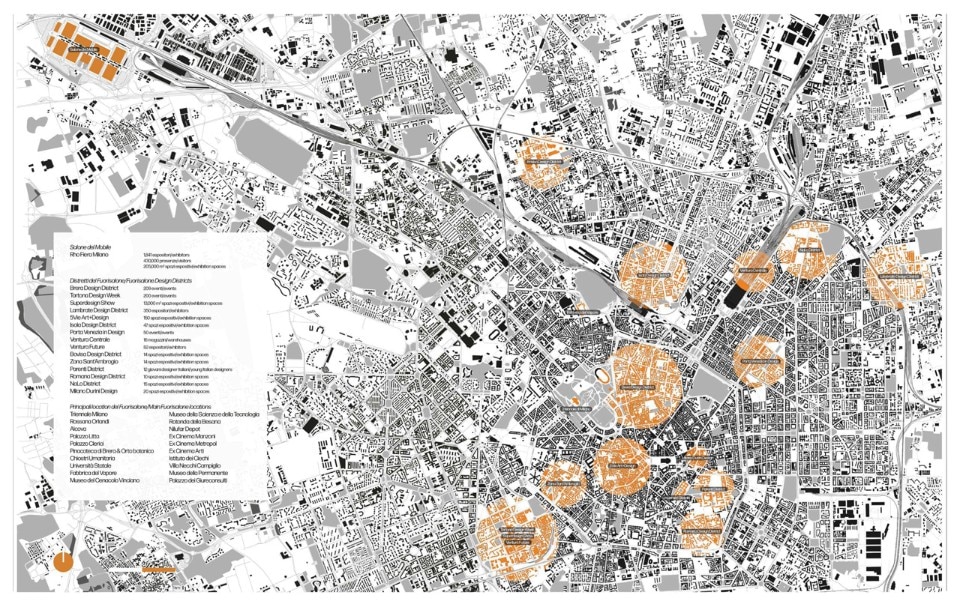

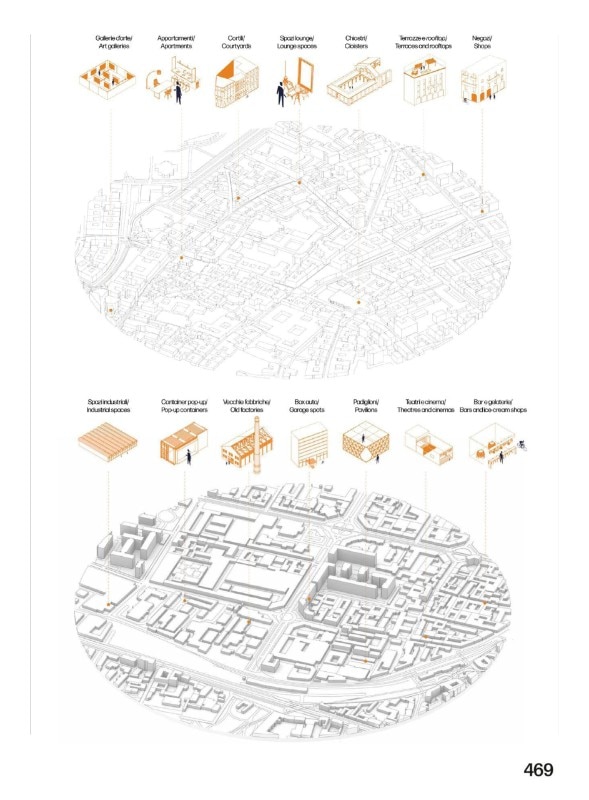

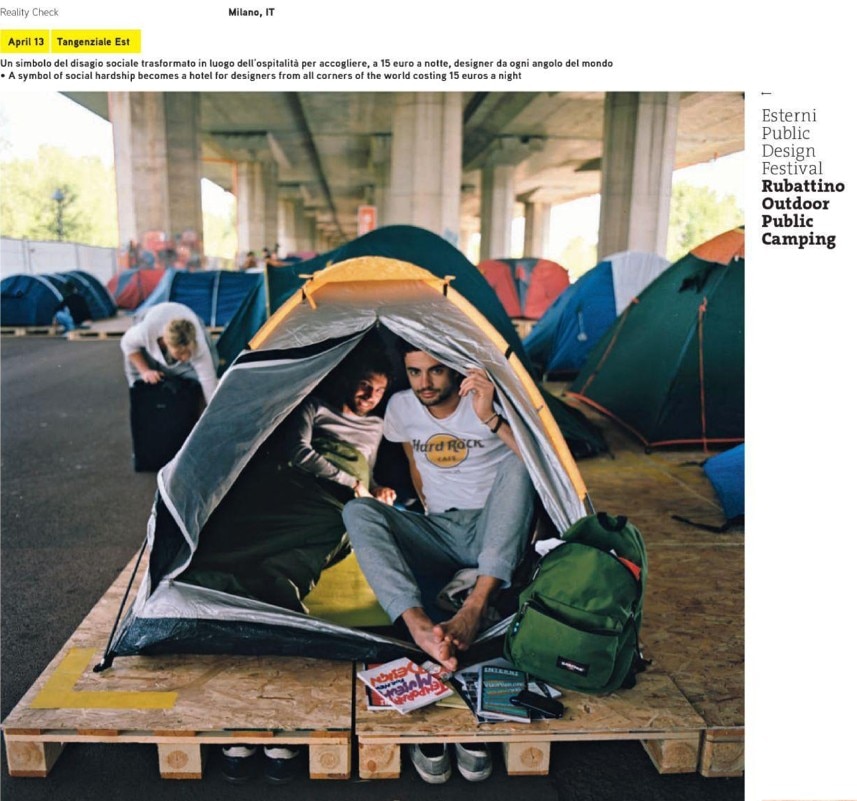

Such discourse would continue even after the 2008 crisis redefined all questions and priorities, and the main nature of the Salone became a combination of Fuorisalone, of questions on how we inhabit this world, of temporary placemaking and citymaking practices. Domus and the Salone found themselves together again inside the same discourse involving all Design Week actors, global actors, and the city of Milan. The involvement of Domus became all but intangible, as witnessed by events such as the one-night opening of the San Siro stadium, turned into a public square in 2005, or Domus Voices in 2014, at the Conservatorium cloisters.

In pre-pandemic times already, the discourse had turned the spotlight on responsibilities of design towards the planet, towards cities, towards people. In 2019, a Winy-Maas-guest-edited Domus ( claim of the year was “Everything is urbanism” ) published a visual research essay on the intangible impact of Design Week on the city of Milan, and not much later Dejan Sudjic drew a sharp outline of the discourse:

“If we can understand the practice of design as a continuing struggle between William Morris and Raymond Loewy, that is to say between a sense of social purpose and testosterone-fuelled shape-making guided by the profit motive, then Morris’s legacy is currently in the ascendant.”

(Is it too late for design to save the world, Domus 1045, April 2020)

As we try to come out of our shelters after the brutal Covid-related disruption, the questions that were left open are coming back with an ever greater power, questioning the ultimate nature of the Salone itself through the position that David Chipperfield outlined in 2020 while reflecting on the cancellation of a “both impressive and concerning (…) Tower of Babel, brimming with ingenuity and design, and staggering in its dimensions.” This position can be summarized by these few lines:

“Without no doubt we need to be less complicit in the concerns and priorities of consumerism but above all we need to seek beauty, to cherish it, to protect it and give it form whenever we can find it.”

(In praise of beauty, in the face of crisis, Domus 1045, April 2020)