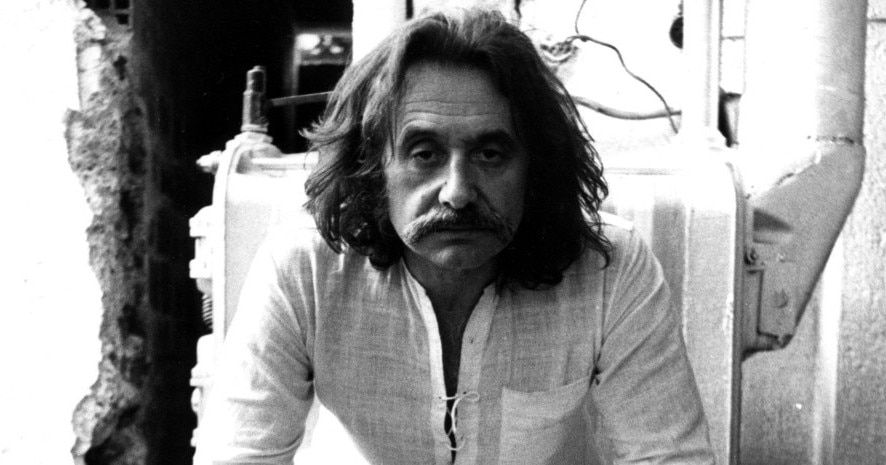

Ettore Sottsass (1917–2007) was born in Innsbruck in 1917. His father (Ettore Sottsass Senior) was an architect and his mother was Austrian. Having graduated from the Galileo Ferraris high school, he enrolled in the Department of Architecture at the Turin Polytechnic, where he graduated in 1939. Enlisted during the Second World War, he was imprisoned for approximately six years. On finally being released, he returned to Italy in 1947 and began working in Milan – where he met Giuseppe Pagano – first of all with his father and then later opening his own design studio.

In 1948 he joined MAC, the Concrete Art Movement, and took part as an artist in the first collective exhibition dedicated to this art form. As well as his passion for art and design, Sottsass also actively dedicated his time to photography.

His meeting with the entrepreneur Sergio Camiulli led to him becoming the art director for Poltronova in 1957, for which he was to design the “Superbox”, a series of wardrobes clad in printed laminate with stripes, or designs inspired by road signs or petrol pumps, a furniture line which included “Barbarella” (1965) and the “Ultrafragola” mirror (1970).

In 1958 he began his long-term collaboration with Olivetti, as a design consultant. His relationship with the company lasted for more than thirty years and earned Sottsass numerous awards, including three Golden Compasses. For the Ivrea-based company, his work included the design of the first Italian mainframe computer, the “Elea 9003” (1959) and a wide range of typewriters, including the “Praxis” (1964), “Tekne” (1964), and the famous “Valentine” (1969, together with Perry King). As well as these, he also designed the “Logos 27” (1963), “Summa-19” (1970), “Divisumma 26” calculators, and the “Synthesis” office system (1973).

During these initial years of activity, Sottsass developed a vision of design as an instrument for social criticism, which led him to maintain that “Design is one way to discuss life. It is a way to discuss society, politics, eroticism, food and even design. Lastly, it is a way to build a possible figurative utopia or to build a metaphor of life. Of course, for me, design is not limited to the need to lend more or less form to a stupid product destined for a more or less sophisticated industry; therefore, if you have to teach anything about design, it should be, above all, something about life, and you should stress this point, explaining that technology is a metaphor for life”.

This led to his adherence to the principles of Radical Design. Together with the “Alchymia” group, he exhibited at the Design Forum in Linz (1979) with the “Seggiolina da pranzo” (in chrome-plated and Abet-print laminated iron), the “Svicolo” floor lamp (which produced light in pop colours with the use of pink and black neon) and the side table “Le strutture tremano”, objects in which the alchemy of the most varied of forms, colours and materials created new aesthetic canons which aimed at moving beyond the idea that decoration is a crime.

In 1980 he first founded “Memphis” in collaboration with other designers, including Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki, Andrea Branzi and Michele de Lucchi, with the aim of providing objects with “a symbolic, emotive and ritual aspect” The underlying principle of absurd and monumental furniture is emotion, more than function”. This was followed by the setting up of the Ettore Sottsass Associati firm, which included Aldo Cibic, Matteo Thun, Marco Zanini and Marco Marabelli. Memorable designs from this period included the “Carlton” (1981) and “Cargo” (1979) bookcases, and the “Tatar” table (1985).

Much loved abroad, he was chosen by Emilio Ambasz to represent new Italian design at the epic exhibition held at the MoMA intitled “Italy. The new domestic landscape” (1972), and was the subject of numerous solo shows, including that organised by Cooper Hewitt in New York and at the International Design Zentrum in Berlin (both of which took place in 1976). At the MoMA he presented a prototype entitled “Micro Environment”, with which he sought to move away from the typically functionalist distinction of the home into different rooms according to the use made. Sottsass described the project as “a system of plastic ‘containers’ for home furnishings. These containers allowed for the construction of a domestic environment which was adaptable in any moment to the needs of the inhabitants.

The idea is that necessity ‘furnishes’ the home. In other words, while up to this point the scene for domestic drama or comedy has always been the same (as in Greek theatre), the scene can now change easily according to each transformation of situation. This possibility of changing the scene could modify or allow to modify (I think) even the very material of the drama or comedy or domestic ritual” (1971).

His activity in the field of design was often accompanied by critical activity, which for example led him to set up the magazine “Terrazzo” in 1988, with an editorial team involving Barbara Radice, Christoph Radl, Anna Wagner and Santi Caleca. Dedicated to design and architecture, it was published in thirteen issues up to 1996.

Profoundly disappointed by Italian mass production, which he blamed for provoking the society of consumerism, form the 1990s onwards Sottsass reduced his work as a designer to just a few interventions for art galleries, instead dedicating his work ever increasingly to architecture.

Among his building projects, which are less well-known that his design work, of note are the Wolf house in Ridgeway, Colorado (1986-1986); the condominium in Viale Roma, in Marina di Massa (1985), the Mourmans Villa in Lanaken, Belgium (1995-2001, with Johanna Grawunder), and an entire village in Singapore (2000). All these works were centred on humankind, and what is notable is the attempt to establish a connection between the natural and the artificial on the one hand, and between new construction and genius loci on the other.

As Sottsass would say, “the ritual of architecture is practised to create a space that before the ritual was not real. A space becomes real when it is solid with attributes and heavy with meaning, when it is condensed - like a broth - with presences and ideas, when it is dripping - like a dense colour - with surprises and transformations, when it pales with shadow and is corrupted by light” (1956).

He died in Milan on 31 December 2007 at the age of ninety, after having received many prizes and recognitions, including an honorary doctoral degree from the Royal College of Art in London, (1976), Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Republic (1992), the IF Award Design Kopfe from the Industrie Forum Design in Hannover (1994), the nomination as Honorary Doctor of the Royal College of Art in London (1996) and the Oribe Award from the city of Gifu in Japan. He was Grand Officer for the Order of Merit from 2002 until his death.

In the words of Hans Hollein:

Sottsass is a magician. Without Sottsass our life would be colourless

- Born:

- 1917–2007

- Professional role:

- architect, designer, artist