Among the essays in Umberto Eco’s collection Il secondo diario minimo (Milan, Bompiani, 1992), in the chapter devoted to “Instructions for Use,” there is one titled How to Justify a Private Library. Here, the author frees from guilt anyone who, upon entering a bookstore, is struck by a kind of Stendhal syndrome mixed with literary FOMO, and feels an urgent desire to buy new books for their private collection, even while knowing they won’t be able to read them right away. Accumulating books, Eco says, is a way of building a personal reserve of knowledge: texts to consult, others to begin in the future, and many that will remain on moderately dusty shelves waiting for the right moment to be opened.

This is certainly one of the reasons why the physical book continues to exert its charm, despite the spread of e-readers and digital devices. Also thanks to a broader renewed interest in the analog — as has happened with vinyl records, cassette tapes, and film photography — the book maintains a material presence that also involves the particularity of the place where it is purchased. In this context, bookstores become even more important as spaces that directly shape the experience of discovery, selection, and the pleasure of buying.

View gallery

View gallery

Some bookstores across the five continents stand out for a variety of reasons. For example, Tiny Tiny Bookstore in Japan is recognized by Guinness World Records as the smallest bookstore in the world, where, due to its size and book selection, only children can enter; Livraria Bertrand, located at 73 Rua Garrett in Lisbon, is the oldest bookstore in the world still in operation, founded in 1732; while on Mont Blanc, at the Punta Helbronner station, there is laFeltrinelli 3466, the highest bookstore in Europe at 3,466 meters above sea level, inaugurated in 2019. It’s also impossible not to mention the “18 miles of books” at Strand Bookstore in New York, the only survivor of Book Row, a city district where, between the late nineteenth century and the 1960s, more than thirty bookshops once stood.

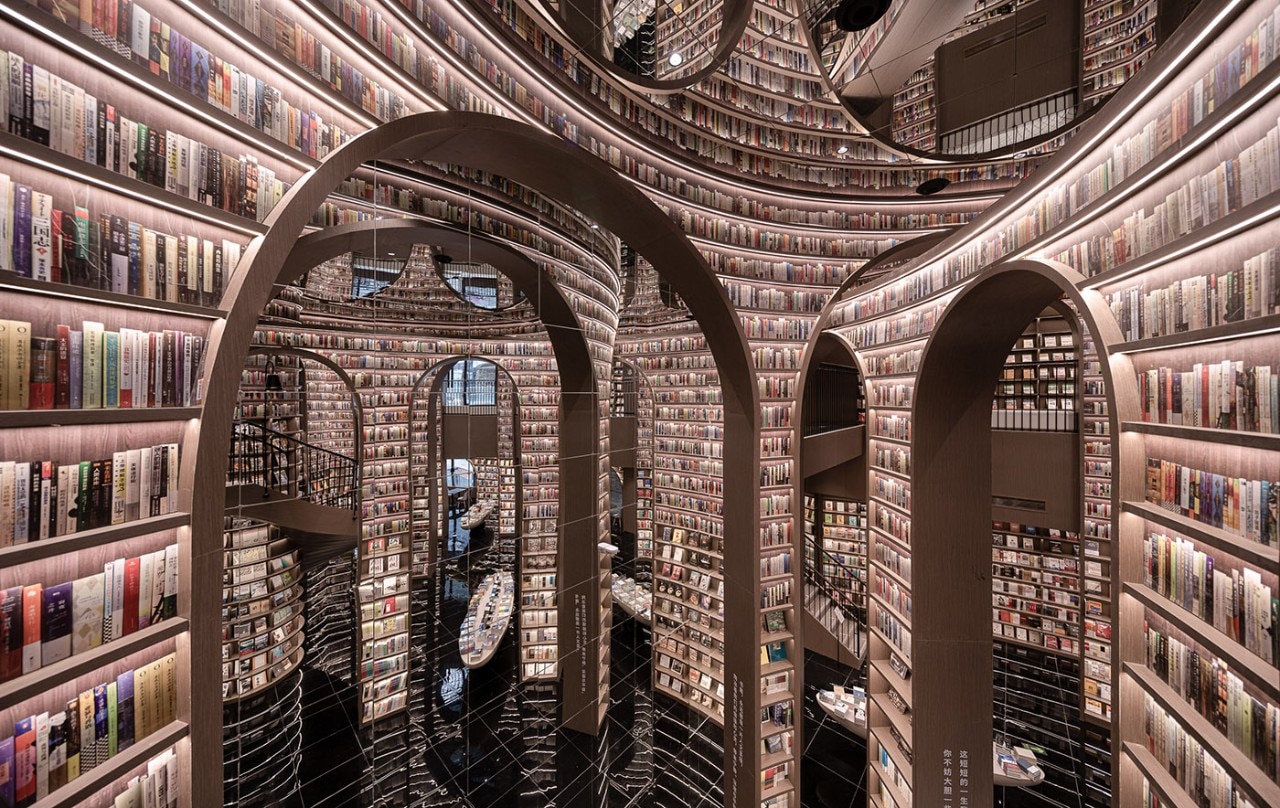

Among the countries that in recent decades have seen the opening of bookstores in incredible purpose-built structures, China certainly stands out. In Qianhai there is the largest bookstore in the world, with its 131,000 square meters: the Eye of the Bay Area, housing 300,000 volumes divided into nearly 100,000 thematic categories. This futuristic architecture integrates different thematic spaces such as the Art Garden, the Cultural Kaleidoscope for the humanities, a theater, exhibition galleries, and a science fiction center, anticipating the contemporary Chinese model of the bookstore as a hybrid space and cultural destination. At the same time, numerous bookstores are part of urban or rural regeneration programs, contributing to the recovery of existing buildings or the reactivation of small towns, often in direct dialogue with the natural landscape.

View gallery

View gallery

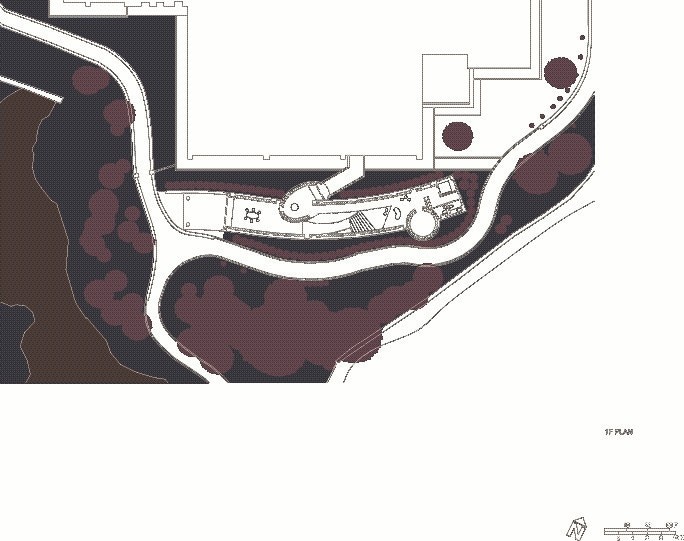

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

BRH+ / Barbara Brondi & Marco Rainò, Libreria Luxemburg, Turin, 2025

Photo © pepe fotografia

It may seem contradictory that in China — known for its censorship regulations, especially regarding political content — bookstores are the protagonists of ambitious architectural projects, but this is not an isolated case. In Tehran, in 2017, one of the world’s largest buildings dedicated to reading opened: the Tehran Book Garden. Although Iran has imposed very strict censorship, including on literary works allowed to circulate in the country — from which even The Da Vinci Code and James Joyce’s Ulysses have not escaped — Iran is one of the countries in the Middle East with the highest literacy rate (over 90% in 2025). For this reason, the construction of an architectural complex such as the Book Garden — covering an area of 100,000 square meters and housing over 200,000 volumes, both for consultation and for sale — should not be surprising.

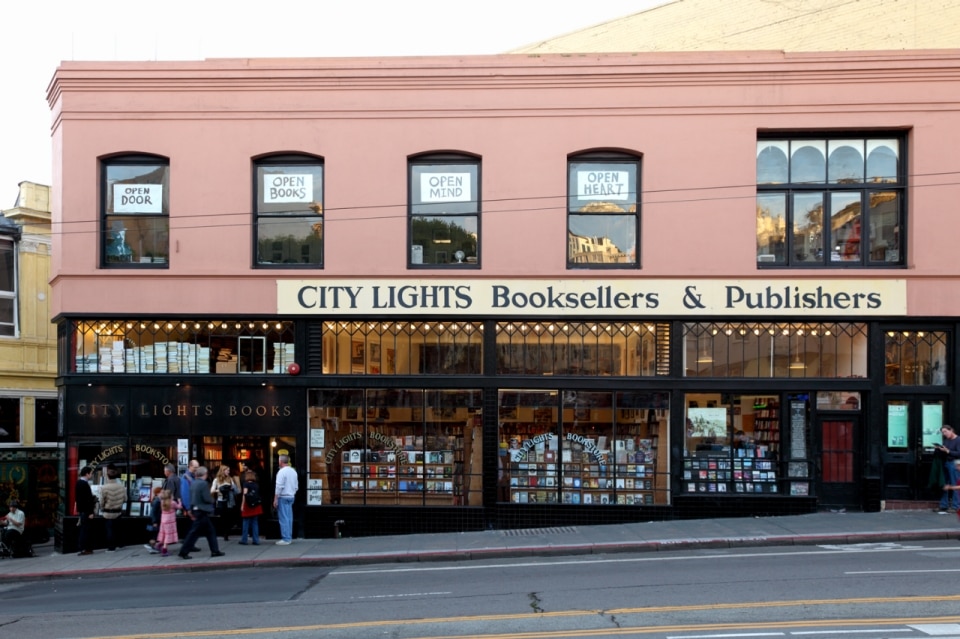

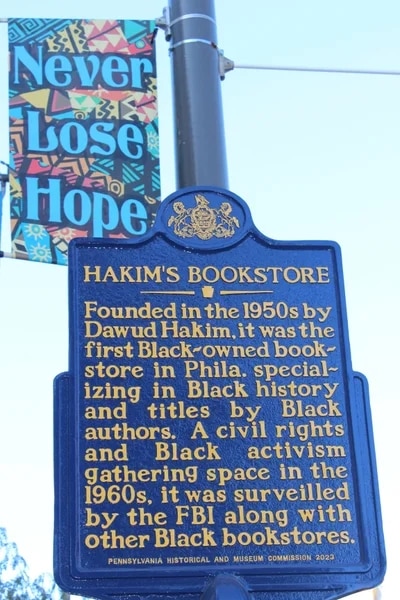

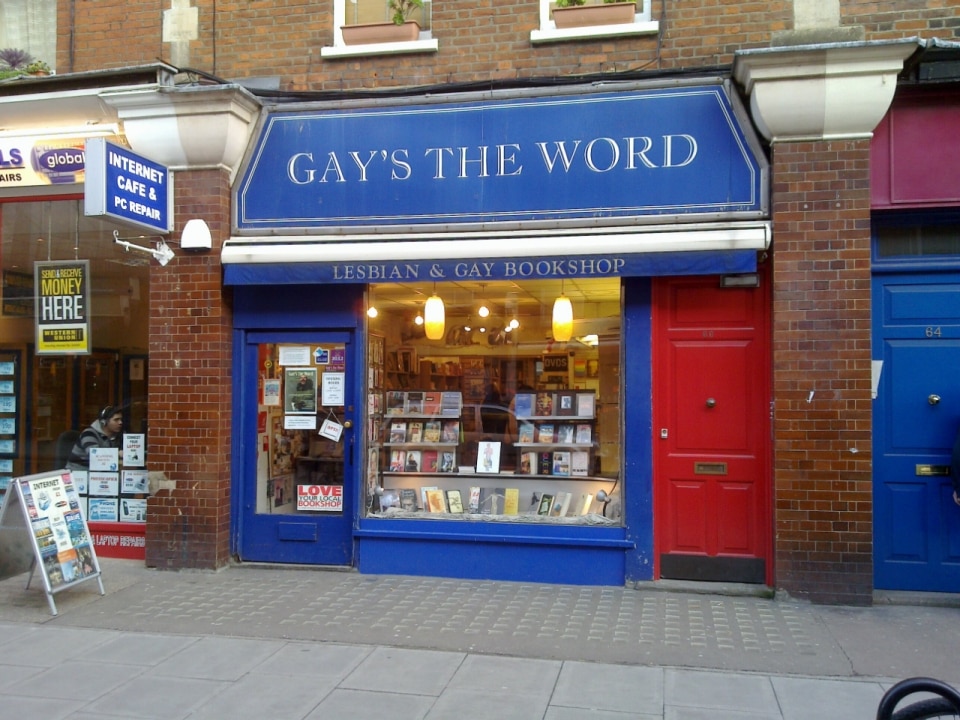

And if, alas, someone wonders whether we still need bookstores in the twenty-first century, it is worth remembering that bookshops, in addition to being commercial activities, are also civic institutions that can become synonymous with resistance. One example is the story of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York, the first bookstore dedicated to authors from the queer community, opened in 1967 and closed in 2009. It was founded by activist Craig L. Rodwell, one of the promoters of New York’s first Gay Pride and a key figure in the LGBTQ+ liberation movement before and after Stonewall. For more recent confirmation, one need only look at what is happening in Ukraine, where, since the beginning of the war, dozens of new bookstores have opened, including Sens bookstore in 2024, the largest in the country, in the heart of Kyiv.

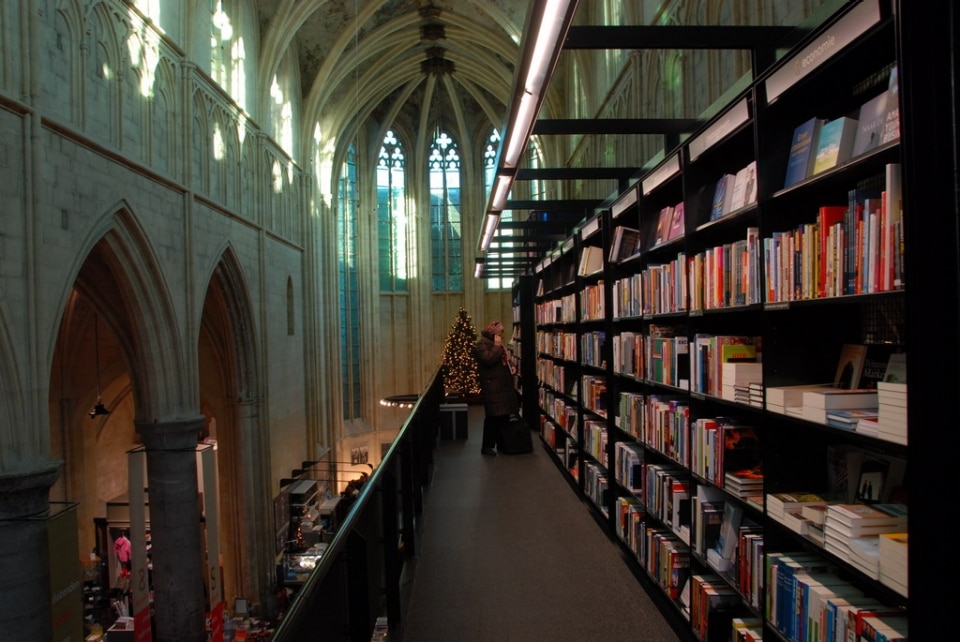

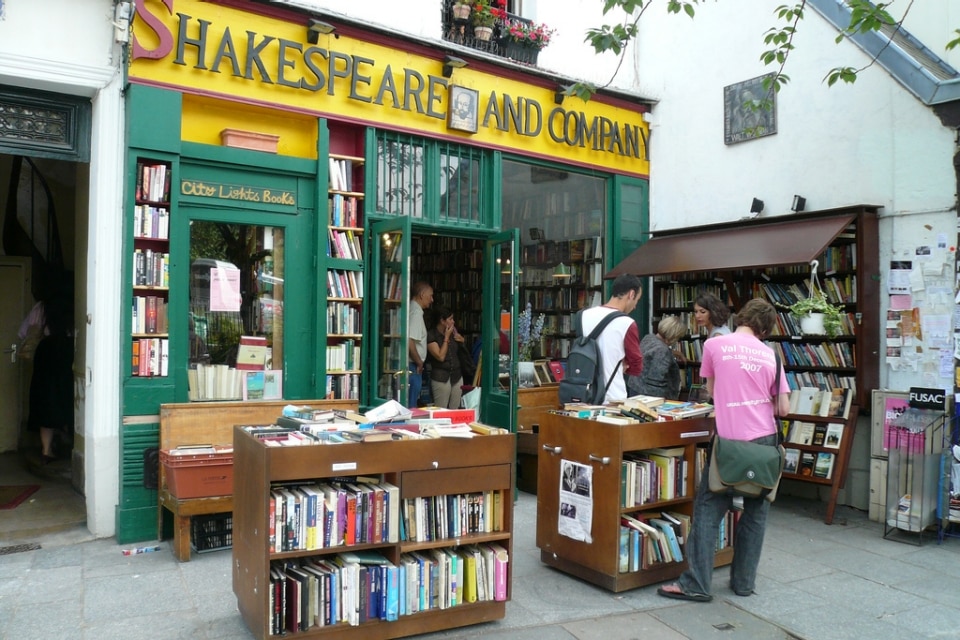

Today, the possibility of telling an ever wider audience the stories behind independent bookstores around the world, and the architectural experiments behind increasingly extraordinary bookshops, is turning stores for books and magazines into destinations to be included in travel itineraries, also thanks to major luxury brands and publishers with strong identities who choose to invest in this sector. Domus presents twenty bookstores to visit at least once in a lifetime, selected for the architectural value of their spaces, their history, and the way they interpret the relationship between publishing, design, and the context of use.