The last major Richard Rogers retrospective in London was in 2013 at the Royal Academy of Arts. It was titled “Inside Out”, alluding to the Anglo-Italian’s role in authoring the “high-tech” movement, which he co-pioneered with his early-career colleague Renzo Piano. The movement radically exposed the mechanics of buildings as the highest gesture of legibility and tribute to technological advancement. The 2013 exhibition also chronicled Rogers’ career-long thinking on city-making as a social science.

Today, an exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum tells a more personal story of Rogers’ architectural and urbanist approach. Far more compact than its Royal Academy predecessor, “Richard Rogers: Talking Buildings” occupies two rooms, delving into his thinking via eight of his projects – six built, two unrealised. Curated by his son, Ab Rogers, the exhibition is intended to be chronologically non-linear, albeit selecting buildings that begin at the start of his career – Zip-Up House (1967) – and ones that mark its end – Drawing Gallery (2020). The show has been designed for visitors to “ping-pong” from one project to another, discovering both the commonalities and diversity that Rogers had when addressing some of humankind’s most “essential concerns”.

Within the acoustically intimate, Georgian proportions of the Soane house, a recording of Rogers’ voice recalls the inspiration he took from a wristwatch his mother gave him that had colourfully exposed mechanics. He talks about the act of “humanising of parts” so that people can read them, and how that becomes integral to design that serves individuals and societies. He goes on to describe being influenced by Italian ideas of humanism in his formative years – he was born in Florence in 1933.

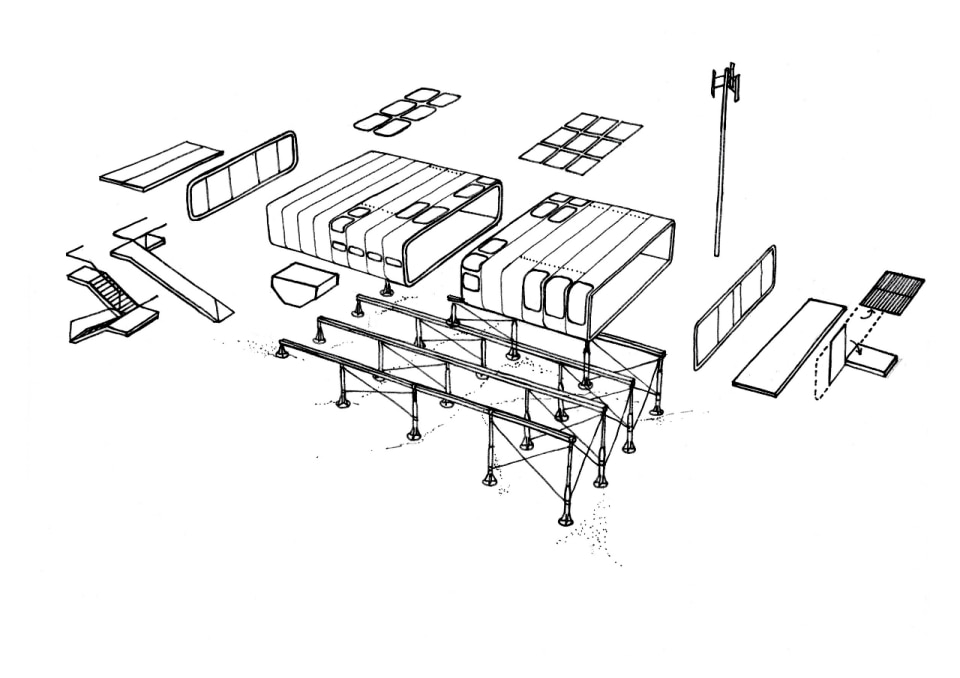

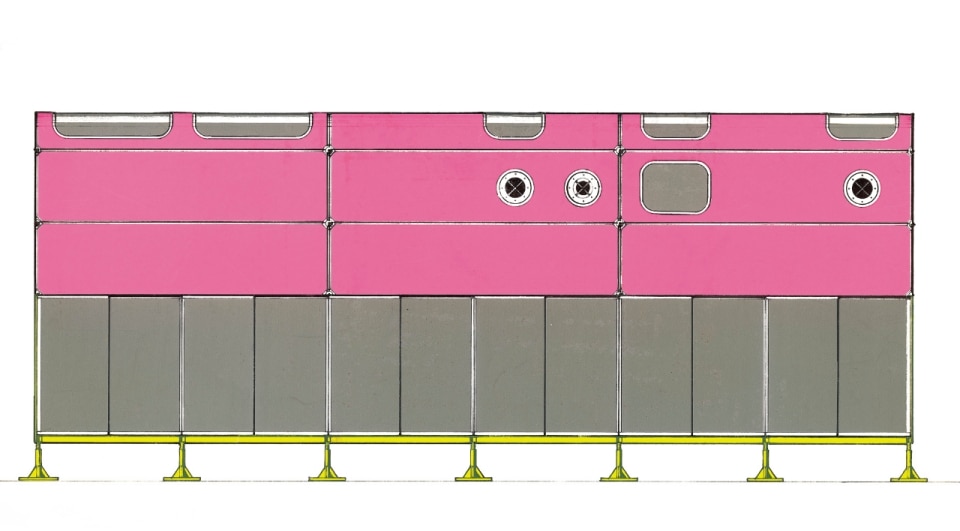

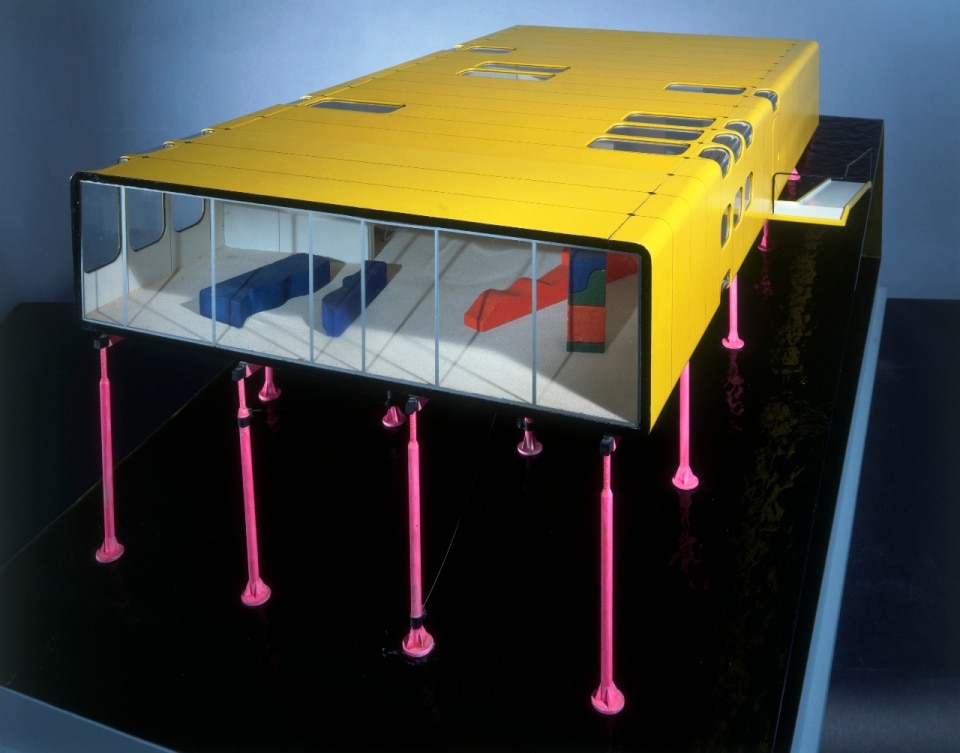

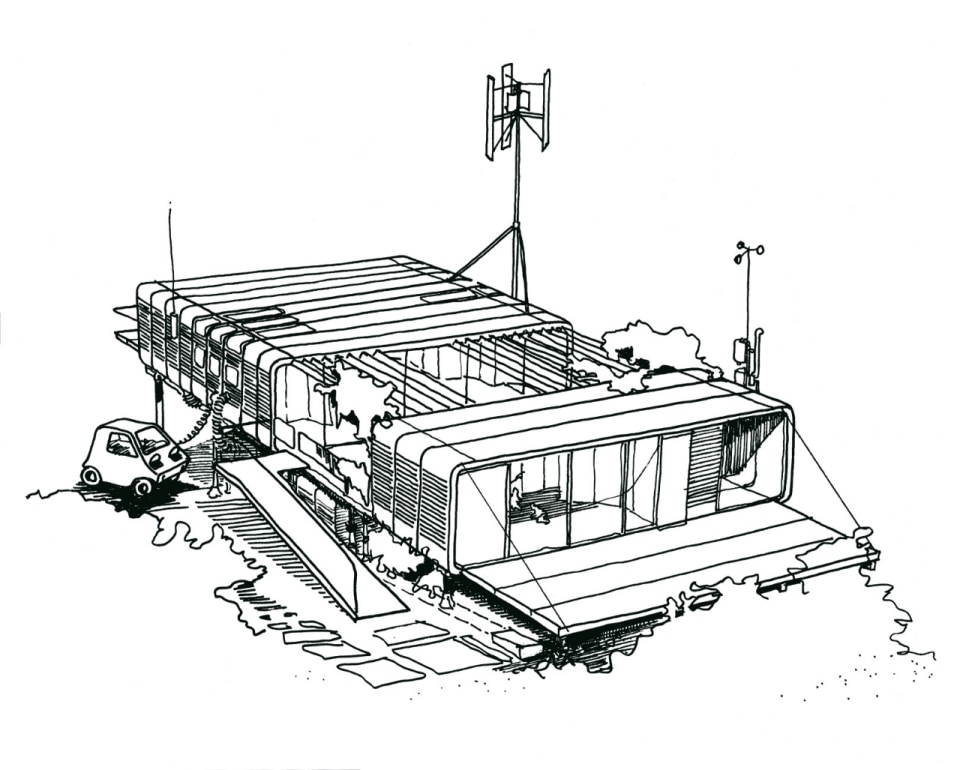

Rogers’ interpretations of humanistic design play out differently across each project. In Zip-Up House, which he designed with Su Rogers, he brought ideas of modularity to the challenge of creating a “House of Today” – the name of the competition it was created for. The aim was to design with autonomy from site. The house was envisioned as moveable, built from a kit of parts in an approach that is well-rehearsed today, yet was a relatively young idea when the project emerged.

Nearly fifty years later, in his Tree House project, Rogers scales up his prefabricated ambitions to “rethink a democratic, mass-produced solution for housing”. The concept is simple – a stacked tower of timber units with a central core that transports people who live in the wooden boxes to and from two levels of shared space – cafes and communal amenities at ground, and garden spaces on the roof. The project addresses ongoing streams of Rogers’ societal and environmental concerns in one vertical swoop. It rises upwards in locally sourced materials to help the planet; it remains dense and compositionally adaptable to accommodate social change. It was never built.

These drawings best encapsulate the architect’s modern-day definition of humanism – where the ultimate spatial altruism is the ability to accommodate progress and anticipate change.

The exhibition naturally includes Rogers’ most iconic and well-known projects – Centre Pompidou (1977) by Piano + Rogers, and Terminal 4 at Madrid-Barajas Airport (2005) by Richard Rogers Partnership – exhibited in intricate models and arresting large-scale drawings. And then in Rogers’ 1999 design for London’s Millenium Dome, the expression of democratic design is defined by adaptability. Resembling a pop-art poster, the plan colourfully reveals the project’s original design for 12 pavilions, laid out internally in sundial format. It describes ideas of “maximum versatility” and ‘non-hierarchical” spaces, which could support a future of public entertainment and events without boundary.

In the second and final room, Rogers’ work on Lloyd’s of London (1986) emblematises the glorification of what he terms ‘urban vitality’ when he produced writings On Modern Architecture – first in 1990 and then in 2013. The project, which was designed to expand or contract according to the needs of its client’s oscillating insurance market, gives shape to Rogers’ description of “controlled randomness, which can respond to complex situations and relationships”.

The building pulls services to the exterior to alleviate space inside. Set against the signature bright colours that seem to be hereditary to the Rogers family, these drawings best encapsulate the architect’s modern-day definition of humanism – where the ultimate spatial altruism is the ability to accommodate progress and anticipate change.

Opening image: Casa Rogers © arcaidimages.com