If it is a fact that we live in a world in constant motion, why must architecture be static? A question, this one, that runs through the history of modern and contemporary architectural thought: from the mechanistic approaches inebriated by speed and techno-scientific progress characteristic of the Avant-gardes, the Modern Movement, radical megastructures and High Tech; to the explorations of urban systems as complex organic entities in perpetual transformation/proliferation of the Japanese Metabolism of the 1960s; to more recent works investigating multiple forms of interaction with the environment (from Jean Nouvel's optical screens, to Neri Oxman's ecologically programmed skyscrapers as symbionts of the environment).

These issues have recently been extensively investigated in the exhibition “Architettura Instabile” curated and set up by the Diller Scofidio + Renfro studio at the MAXXI in Rome (until March 2025) which, emphasizing a critical interpretation of the Vitruvian “firmitas,” offered insights into architecture in motion as a possible response to the instability imposed by the flows of a “liquid” society (cit. Zygmunt Bauman), contemporary geo-politics and natural disasters.

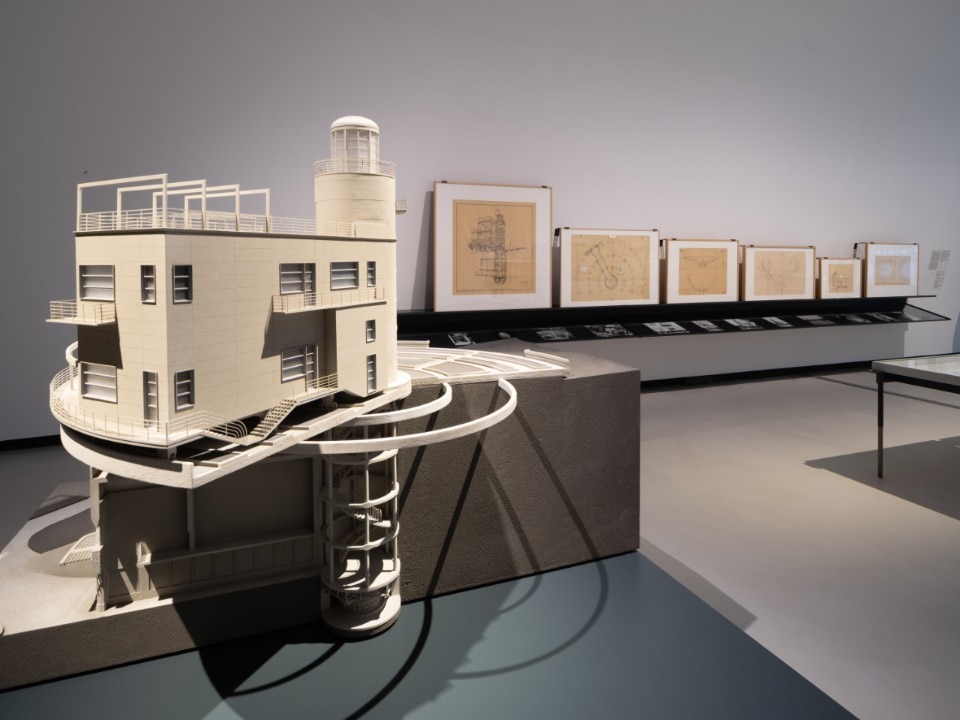

And it is precisely within this cultural groove that a work as unique as quite unknown, also rightly included in the Roman exhibition in the section dedicated to “ecodynamic” architectures, fits in: it is the Villa “Il Girasole”, conceived and built between 1929 and 1935 by engineer and entrepreneur Angelo Invernizzi, together with architect Ettore Fagiuoli and mechanical engineer Romolo Carapacchi, in Marcellise near Verona, where the building seems docked like an unlikely ship among the cherry trees.

The villa is the manifesto of a “responsive” architecture that, instead of opposing or reacting passively to natural forces, accommodates them: to dictate the rules of response in this case is the sun, which the house “follows” in its perennial daily cycle from east to west like a “mechanical flower” rotating on itself to intercept the changing light, fluctuating temperatures and atmospheric fluctuations throughout the day.

A ‘tour’ on a realized utopia, but without vertigo.

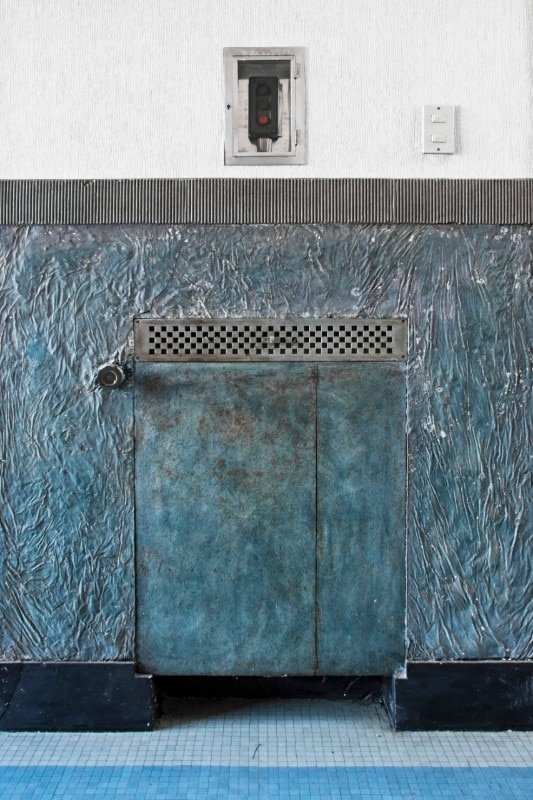

The building consists of a three-story circular basement leaning against the natural slope of the land, on which rests a two-story volume with an “L” layout pivoting on a central cylindrical block including staircase and elevator bodies, and topped by a glass-concrete turret. On the exterior, rigorous rationalist geometries pay homage to nautical architecture through the gleaming, light metal cladding of the facades. Inside, Art Deco atmospheres infused with futurist suggestions pervade the rooms: a large garage and reception rooms in the basement, the family's domestic spaces in the upper volume (with common rooms on the first level and sleeping areas on the second).

A special feature of the work is the upper body's possibility of complete rotation (360°) in two directions around its own axis (corresponding to the central cylindrical block) in a time of 9 hours and 20 minutes at a speed of 4 mm/second: the rotation is given by an electrically activated mechanism consisting of a system of trolleys with railway wheels on a ring of steel rails resting on the floor slab of the building's circular base. An innovative engineering solution, implying both an intimate belief in scientific-technical progress and a yearning for a deeper (and cathartic?) connection with Nature, at a time when the country was “moving” inexorably into the war.

Never open to the public in the past, the villa over the years has maintained a defiladed profile, like a hidden jewel. Featured in 1936 in Architecture magazine, in 2006 a monograph was dedicated to it (Aurelio Galfetti, Kenneth Frampton, Valeria Farinati, Villa Girasole. The Rotating House, Mendrisio Academy Press) that helped foster its notoriety. With the passing of the owners, the sole heir decided to transfer the property, in order to ensure its preservation, to a Swiss foundation named after her parents and subsequently passed under the Cariverona Foundation umbrella. Since the heir's death in 2014, the villa has been in a state of neglect and degradation until 2023, when the establishment of a new Foundation Board of Directors turned the spotlight back on the villa to give it a well-earned centrality in the Italian cultural and architectural scene.

Today the building can be visited by appointment for a “tour” on a realized utopia, but without vertigo (the villa should move a few millimeters per second).

This article is the result of a discussion with the Il Girasole Foundation, partly to clarify the many inaccurate reports currently circulating on digital platforms regarding the construction.