The tumultuous relationship between Italian rationalism and the Fascist regime survives for less than a decade, before their final estrangement. The key question, doomed to a negative answer, is whether and how rationalist architecture can embody in its three dimensions the ideals of the dictatorship, in search of a clear identity and of the monuments to represent it.

The history of Italian rationalism is made of groups, movements, exhibitions and reviews, even more than of architects and buildings. The creation of the Gruppo 7, in 1926, marks the beginning of this short season. Members of the group include Luigi Figini (1903-1984), Guido Frette (1901-1984), Sebastiano Larco, Gino Pollini (1903-1991), Carlo Enrico Rava (1903-1985), Giuseppe Terragni (1904-1943) and Ubaldo Castagnoli, immediately replaced by Adalberto Libera (1903-1963).

The Gruppo 7’s writings set some of the fundamental topics that underpin the theoretical reflection and the built work of all the interpreters of the Italian rationalism: the tension between a “new architecture”, informed of the existence of new technologies, such as reinforced concrete, and oriented towards the construction of a new society; the influences of the European modernism, most notably of Le Corbusier, but also of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius; the will to question the absolute value of these models, and the interest into their local and national rethinking.

In 1928, the Gruppo 7 merges with the MIAR (Movimento italiano per l’architettura razionale), the initiator of the short-lived series of the Esposizioni italiane di architettura razionale. The first edition is organized that same year by Libera and Gaetano Minnucci (1896-1980); the second takes place in 1931, and includes the famous “Tavolo degli orrori”. This gathers a collection of traditionalist buildings commissioned by the regime, selected by the wholeheartedly Fascist Pietro Maria Bardi (1900-1999), as a provocation against his own party. The latter took deep offense, withdrawing its endorsement to the MIAR and virtually causing its dissolution.

The MIAR can count amongst its most prestigious members Giuseppe Pagano (1896-1945), since 1933 the editor-in-chief of Casabella, whose editorial board is based in Milan since 1928. His co-editors are Edoardo Persico (1900-1936), from 1935 until his death, and Anna Maria Mazzucchelli, up to the forced closing of the review by the Fascist authorities, in 1943. Casabella and Quadrante, edited by Bardi and Massimo Bontempelli (1878-1960), are the two main platforms for the debate on Italian rationalism, both engaged in its promotion, though with different attitudes: soft-spoken and problematic for Pagano, polemic and politicized for Bardi.

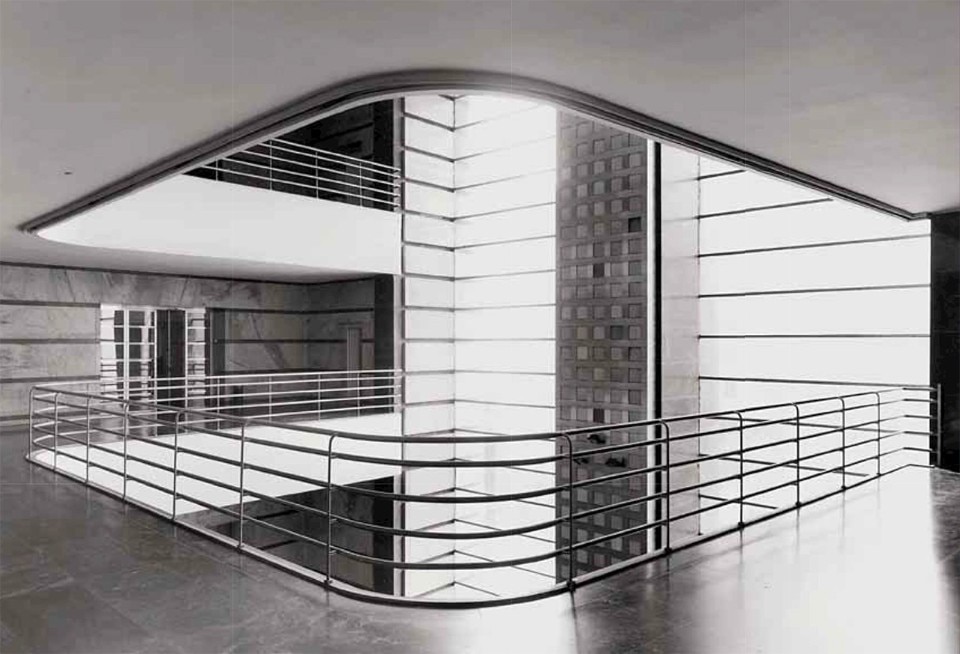

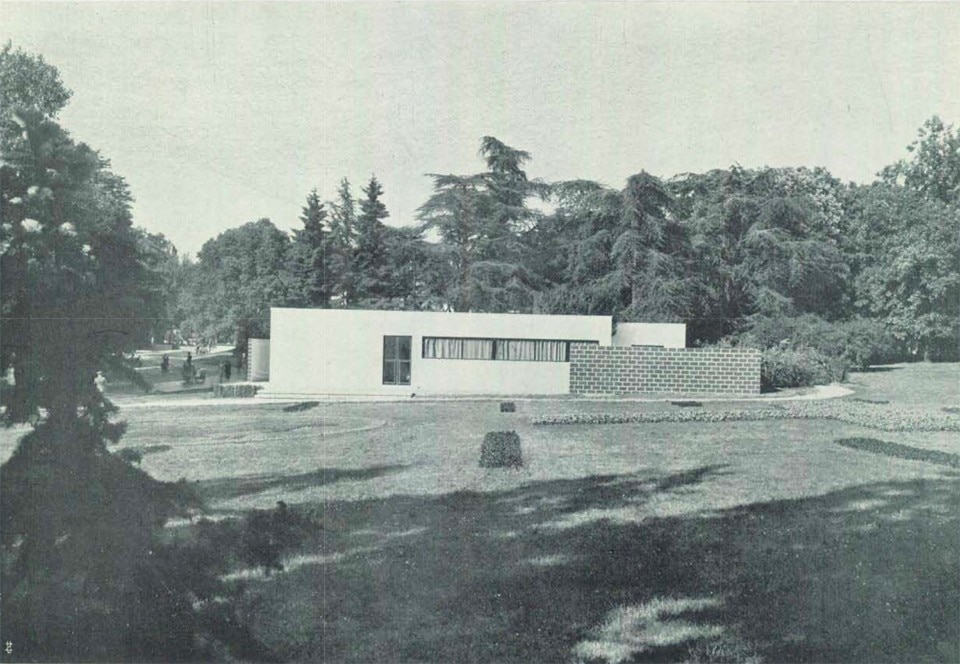

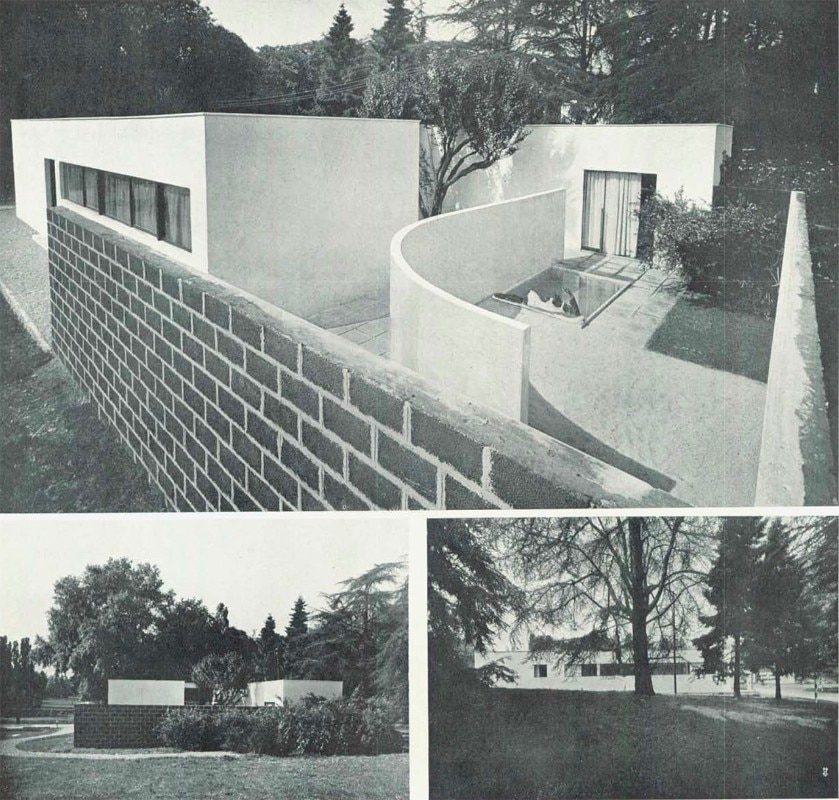

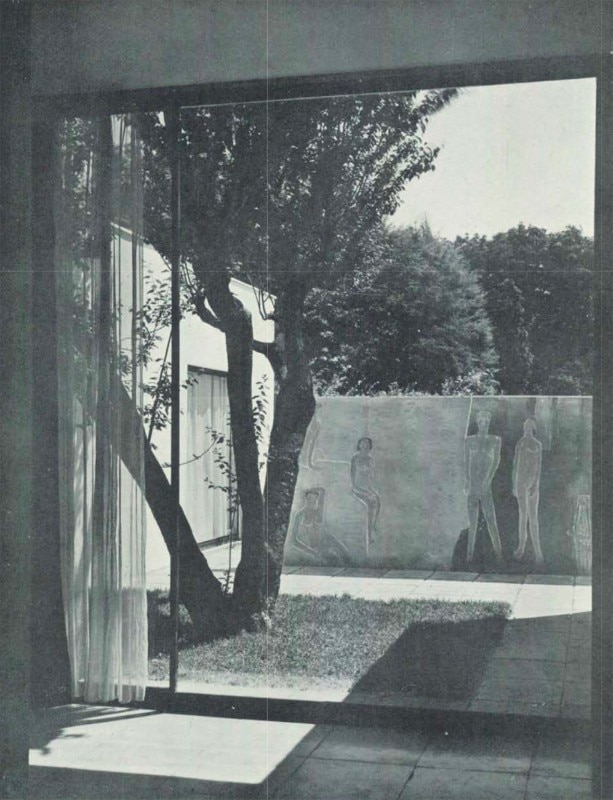

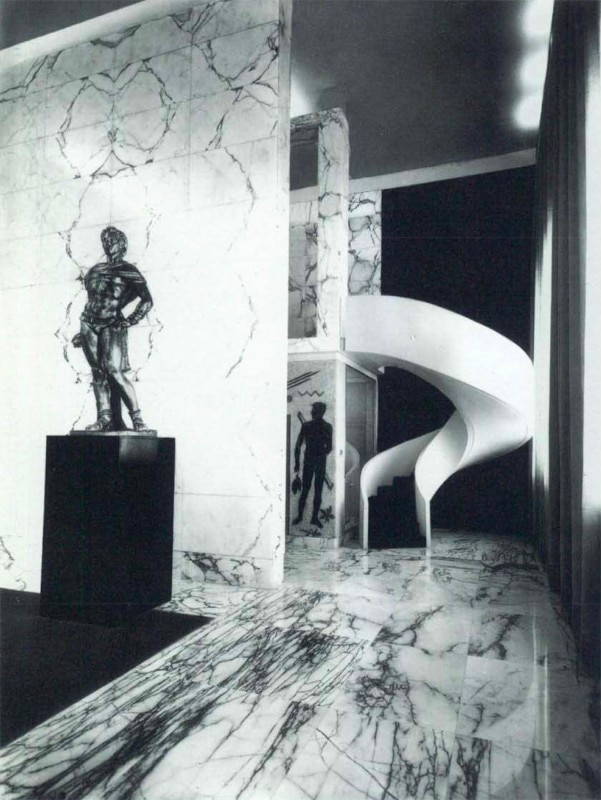

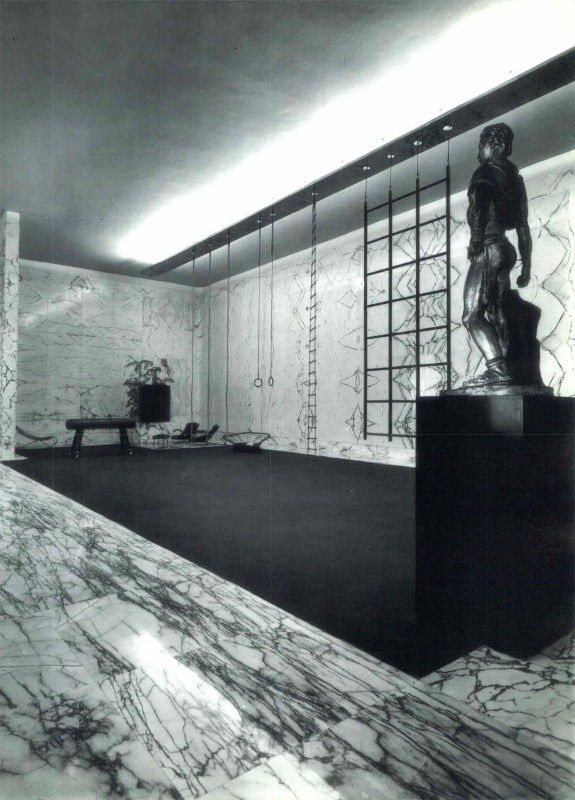

The triennale exhibitions organized initially in Monza and later on in Milan are a valuable occasion to build full-scale models of rationalist architectures. An interesting example is the Casa elettrica, built by Figini and Pollini in 1930 for the IV Esposizione triennale internazionale delle arti decorative ed industriali in Monza. Libera and Frette designed the furniture, while Piero Bottoni (1903-1973) was in charge of the chicken and the bathroom. The building is conceived as a prototype of a rationalist residence, overtly inspired by the five points of Le Corbusier’s architecture.

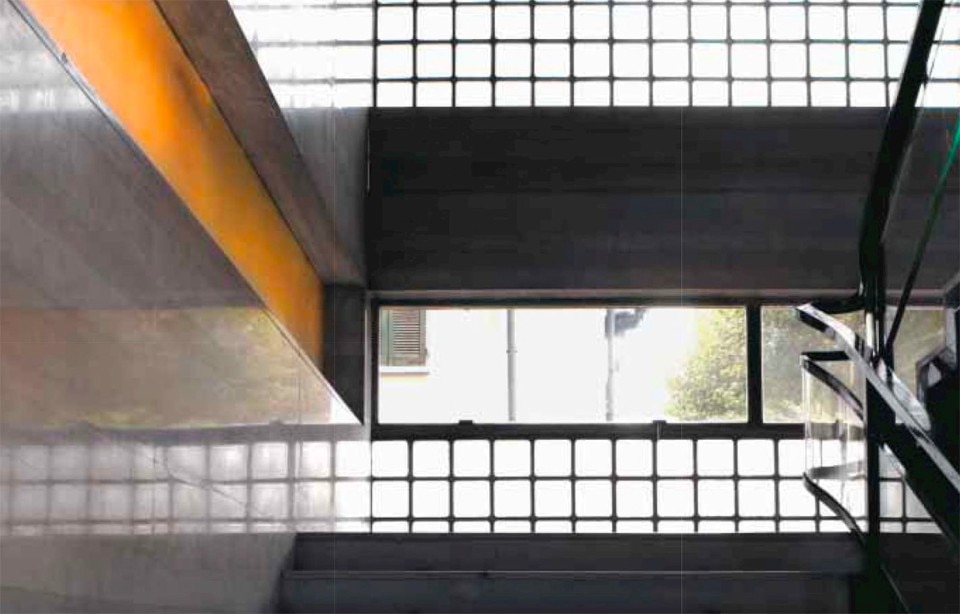

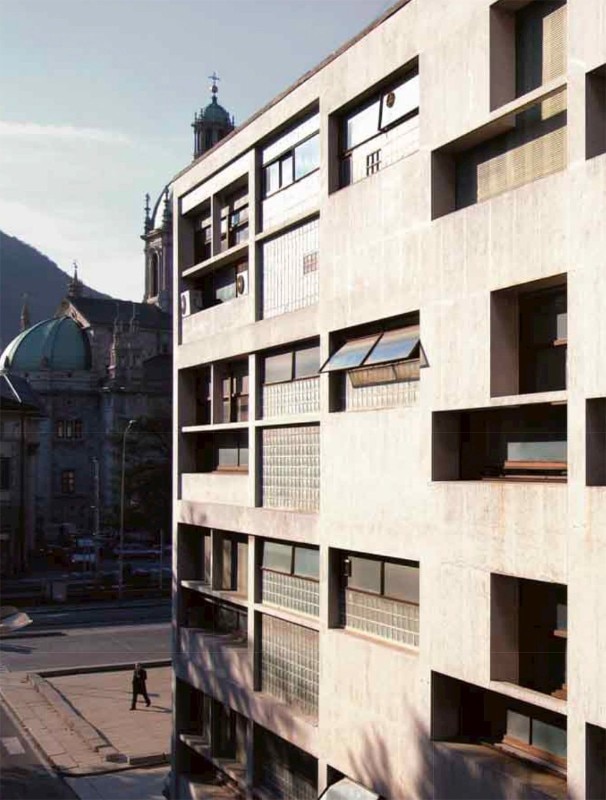

Since the start of the 1920s, and more intensely during the following decade, some isolated rationalist “objects” start to punctuate the landscape of the main Italian cities. Como is the birthplace of Terragni, the undisputed protagonist of Italian rationalism, who proves to be very prolific in his hometown. His major works here include the pioneering residential building Novocomum (1927-1929), the Sant’Elia kindergarten (1936-1937), the Giuliani-Frigerio house (1939-1940) and most of all the Casa del Fascio (1932-1936).

The ambiguities of this building match with the turbulent personality of their author. In the words of Marco Biraghi, within Terragni’s architectures “the Italic matrix – a classic one, and even a baroque one (…) – coexist with no contradiction with their equally irrefutable modernity; similarly, Terragni’s temperament combines without contradictions modern and Fascist ideology”. Generally speaking, much more that the straightforward, uncompromised resolutions of Figini and Pollini’s Casa elettrica, the Casa del Fascio’s elusive character appropriately translates the antinomies underlying the entire experience of the Italian rationalism. The latter remains on the edge between search for modernity and continuity with the past, the ideals of a social renewal and the reality of a totalitarian country.

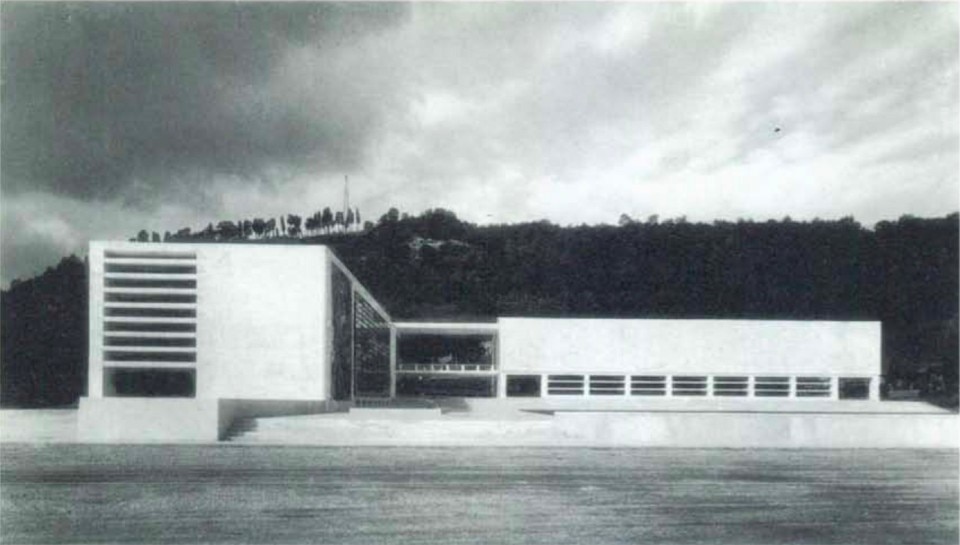

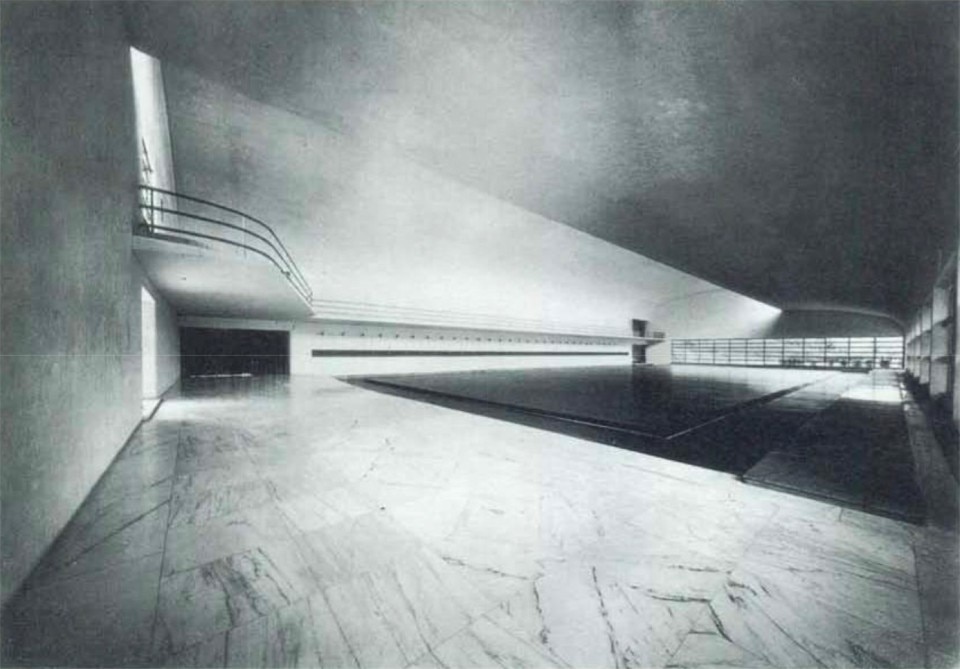

Besides the provincial chief town of Lombardy, rationalist architectures pop up all over the country, in larger cities as well as in smaller towns. In Ivrea, Adriano Olivetti (1901-1960) commissions to Figini and Pollini the complex of the Officine ICO (started in 1939); in Alessandria, Ignazio Gardella (1904-1999) designs the Anti-tuberculosis dispensary (1934-1938); in Milano, Pagano builds the premises of the Bocconi University (1937-1940); in Florence, Giovanni Michelucci (1981-1990) wins the competition for the Santa Maria Novella station (1932-1934); in Rome, Luigi Moretti (1906-1973) designs the Casa delle armi at the Foro Mussolini (1933-1936), Libera and Mario De Renzi (1897-1967) the Post office of via Marmorata (1933-1935), Mario Ridolfi the one of piazza Bologna (1932-1935); in Naples, the Post office (1933-1936) by Giuseppe Vaccaro (1986-1970) rises at the very heart of the demolished neighbourhood called rione Carità. These are all architectures that, in spite of their specificities and differences, confront the contemporary proliferation of historicist buildings. Several of them are designed by Marcello Piacentini (1881-1960), the actual deus ex machina of Italian architecture, and one of the Duce’s closest collaborators.

On the other hand, most of the firmly rationalist projects in the field of urban design and planning won’t be achieved. Amongst them, one of the most experimental is certainly the regional plan for the Valle d’Aosta (1936-1937) by BBPR, the firm lead by Gian Luigi Banfi (1910-1945), Ludovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso (1909-2004), Enrico Peressutti (1908-1976) and Ernesto Nathan Rogers (1909-1969), who also designed the Heliotherapy colony in Legnano (1938). The massive bar built after the Second World War by Bottoni on Corso Sempione, in Milan, is an altered and out-of-context fragment of the ambitious group project for “Milano Verde” (1937, by Pagano and others).

After the collapse of the MIAR, and even more clearly from the mid-1930s, the regime firmly disowns its links with rationalism. Right before the beginning of the war, Fascist architecture identifies with the flashy roman character of Piacentini’s monumental buildings, rather than with Terragni’s abstract classicism.

The leading figures of rationalism, for the most part still very young at the time, will follow different paths. Some of them won’t survive the war, such as Pagano and Banfi, assassinated in the Mathausen concentration camp, and Terragni, weakened on a psychological plan by his experience at the battlefront and killed by a fatal cerebral thrombosis. On the other side, many of the survivors, including BBPR, Bottoni, Figini and Pollini, Gardella and Ridolfi will be on the frontline in the reconstruction of a democratic Italian country.