What Alvar Aalto represented for Finland goes beyond the talent of the designer: together with his wife and partner Aino, Aalto was able to translate the Finnish spirit into modern architecture. This is the case of the Säynätsalo Town Hall, built between 1949 and 1952: with its exposed red bricks and elevated courtyard, it is at once a civic and domestic building, both severe and welcoming, a symbol of a distinctly Nordic and Aalto-esque modernism.

Contrary to certain cold modernist volumes, Aalto designed warm and inviting spaces, and his work is often associated with Organic Architecture—not for specific morphological references to nature or its forms, but for his highly personal, constant pursuit of dialogue between building and place, between the natural and the constructed.

View gallery

View gallery

Paimio Sanatorium (1929–33), Paimio, Finland

Designed as much as a “medical device” as a building, this sanatorium for tuberculosis patients is immersed in the coniferous forest that characterises the Finnish landscape and organised around treatment rooms and terraces. Every detail was patiently designed by Alvar and his first wife, Aino: pastel colours soften the discomfort, the lights do not dazzle, the water flows silently, and the beds and armchairs direct the gaze towards the landscape. Here, functionalism becomes a form of architectural “empathy”.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Viipuri Library (1930–35), now Vyborg, Russia

The Viipuri Municipal Library marked Aalto’s entrance into the international debate: a rigorous volume conceals surprisingly plastic interiors. In the reading room – a rectilinear homage to the circularity of Erik Gunnar Asplund's Library in Stockholm – the undulating wooden ceiling and circular skylights diffuse a uniform, almost shadowless light; in the large lecture hall, the acoustics are shaped by the space. The severe lexicon of functionalism is bent to a softer, more topographical idea of public space.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Viipuri Library (1930–35), now Vyborg, Russia

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Villa Mairea (1938–39), Noormarkku, Finland

Villa Mairea is the most radical manifestation of Aalto's “human-centered modernism”. Commissioned by Maire and Harry Gullichsen – who co-founded the Artek design company with the Aaltos in 1935 – as an experimental home, it intertwines two L-shaped structures that create intimate spaces overlooking the forest. Wood, stone, white plaster and handcrafted details transform the villa into a domestic landscape: the forest-like porch, the irregular swimming pool and the fluid interiors show how the house can be an extension, rather than a negation, of the woods around.

Photo Jarno Kylmänen, Villa Mairea Archives

Villa Mairea (1938–39), Noormarkku, Finland

Photo Jarno Kylmänen, Villa Mairea Archives

House (1934–36) and Aalto Studio (1955–56) in Munkkiniemi, Helsinki, Finland

The Aalto house in Munkkiniemi, with its adjoining studio, is a domestic self-portrait of the designers. The 1936 house combines white plastered volumes and wooden surfaces, between modernism and Finnish rural house; the living room and library overlook the garden. Not far away, the Aalto Studio – completed in 1955 – with its amphitheatre-like courtyard and north-facing workroom, reflects the collective design approach that characterised the studio's modus operandi.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

House (1934–36) and Aalto Studio (1955–56) in Munkkiniemi, Helsinki, Finland

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Church of Santa Maria Assunta (1966–78), Riola di Vergato, Italy

In Riola, in the Apennines near Bologna, a mature Aalto finds a rare testing ground in Italy. The interiors of the Church of Santa Maria Assunta translates the language of Finnish forests into forms of white-painted concrete: the nave is illuminated by a sequence of curved sheds that bring indirect, almost Nordic light into the interior, focusing on the altar. The hall makes liturgy a spatial experience in continuity with the square and the landscape.

Photo Giovanni Comoglio

Paimio Sanatorium (1929–33), Paimio, Finland

Designed as much as a “medical device” as a building, this sanatorium for tuberculosis patients is immersed in the coniferous forest that characterises the Finnish landscape and organised around treatment rooms and terraces. Every detail was patiently designed by Alvar and his first wife, Aino: pastel colours soften the discomfort, the lights do not dazzle, the water flows silently, and the beds and armchairs direct the gaze towards the landscape. Here, functionalism becomes a form of architectural “empathy”.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Viipuri Library (1930–35), now Vyborg, Russia

The Viipuri Municipal Library marked Aalto’s entrance into the international debate: a rigorous volume conceals surprisingly plastic interiors. In the reading room – a rectilinear homage to the circularity of Erik Gunnar Asplund's Library in Stockholm – the undulating wooden ceiling and circular skylights diffuse a uniform, almost shadowless light; in the large lecture hall, the acoustics are shaped by the space. The severe lexicon of functionalism is bent to a softer, more topographical idea of public space.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Viipuri Library (1930–35), now Vyborg, Russia

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Villa Mairea (1938–39), Noormarkku, Finland

Villa Mairea is the most radical manifestation of Aalto's “human-centered modernism”. Commissioned by Maire and Harry Gullichsen – who co-founded the Artek design company with the Aaltos in 1935 – as an experimental home, it intertwines two L-shaped structures that create intimate spaces overlooking the forest. Wood, stone, white plaster and handcrafted details transform the villa into a domestic landscape: the forest-like porch, the irregular swimming pool and the fluid interiors show how the house can be an extension, rather than a negation, of the woods around.

Photo Jarno Kylmänen, Villa Mairea Archives

Villa Mairea (1938–39), Noormarkku, Finland

Photo Jarno Kylmänen, Villa Mairea Archives

House (1934–36) and Aalto Studio (1955–56) in Munkkiniemi, Helsinki, Finland

The Aalto house in Munkkiniemi, with its adjoining studio, is a domestic self-portrait of the designers. The 1936 house combines white plastered volumes and wooden surfaces, between modernism and Finnish rural house; the living room and library overlook the garden. Not far away, the Aalto Studio – completed in 1955 – with its amphitheatre-like courtyard and north-facing workroom, reflects the collective design approach that characterised the studio's modus operandi.

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

House (1934–36) and Aalto Studio (1955–56) in Munkkiniemi, Helsinki, Finland

Photo Maija Holma, Alvar Aalto Foundation

Church of Santa Maria Assunta (1966–78), Riola di Vergato, Italy

In Riola, in the Apennines near Bologna, a mature Aalto finds a rare testing ground in Italy. The interiors of the Church of Santa Maria Assunta translates the language of Finnish forests into forms of white-painted concrete: the nave is illuminated by a sequence of curved sheds that bring indirect, almost Nordic light into the interior, focusing on the altar. The hall makes liturgy a spatial experience in continuity with the square and the landscape.

Photo Giovanni Comoglio

This design philosophy also emerged in Aalto’s projects across Europe, such as the Church of Riola in Italy, but it finds its most authentic expression in Finland’s natural landscapes, as though it were a biological necessity of his architecture.

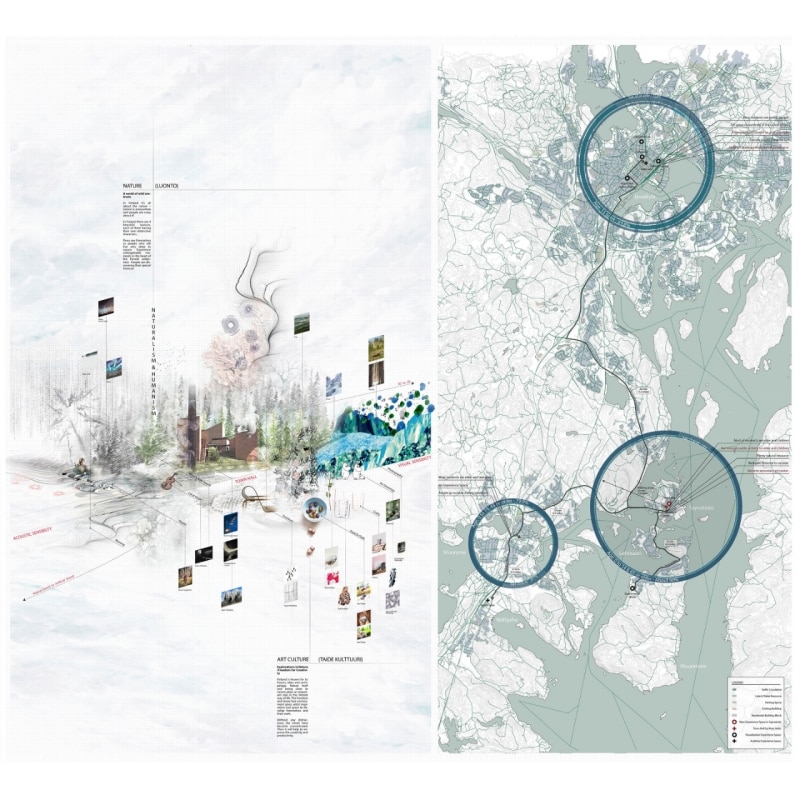

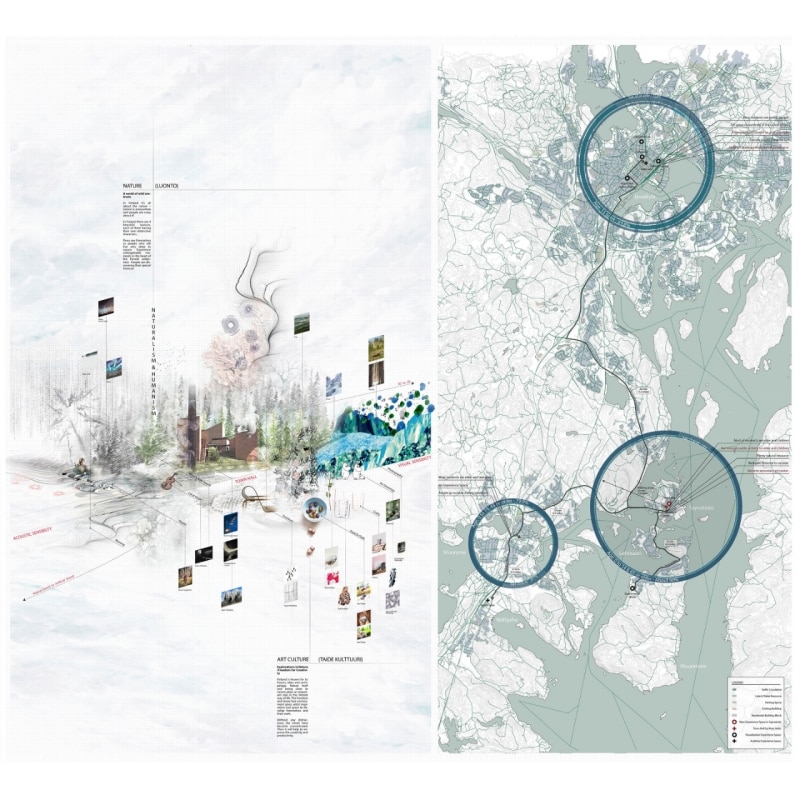

In the future, right beside the red-brick Town Hall, a new cultural center is expected to rise, and among the most appreciated proposals is the one by the Chinese firm Chuxin Tuoyuan.

Why a cultural center is being discussed

Between the 1940s and 1950s, Alvar Aalto was commissioned to design a highly significant building for Säynätsalo, a small settlement located on Lake Päijänne in south-central Finland. By then, he had already designed his most renowned works—today full-fledged twentieth-century manifestos—such as the Paimio Sanatorium, an architecture conceived down to the smallest detail for patients’ recovery and well-being, and the Viipuri Library, built before the city returned under Russian control.

So, shortly after completing the Baker House, the student dormitory commissioned by MIT in Cambridge, Alvar Aalto created the Säynätsalo Town Hall, conceived not only as an administrative center but also a social heart for the community, including a library, public spaces, and residences in addition to offices.

Over time, however, the building has had to face the demographic reality of the island: aging and migration toward Finland’s more attractive cities have gradually depopulated the area. It has thus become necessary to devise strategies to counter this phenomenon, and in recent years several research initiatives on Säynätsalo’s situation have emerged.

Among the ongoing studies is one promoted by the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, an invitation to rethink new forms of community regeneration starting precisely from the function of Aalto’s town hall and the surrounding areas.

A particularly discreet project

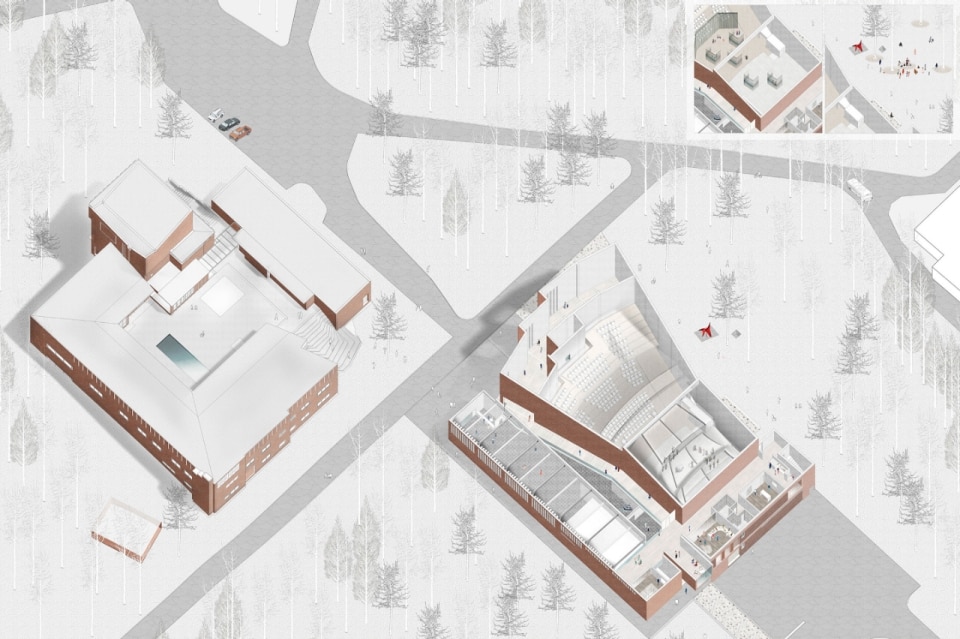

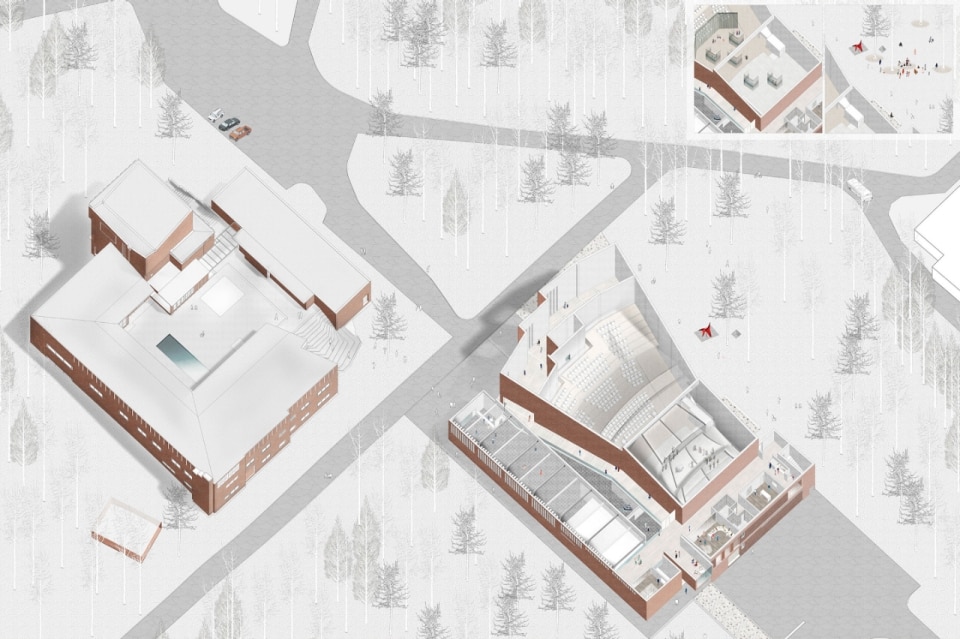

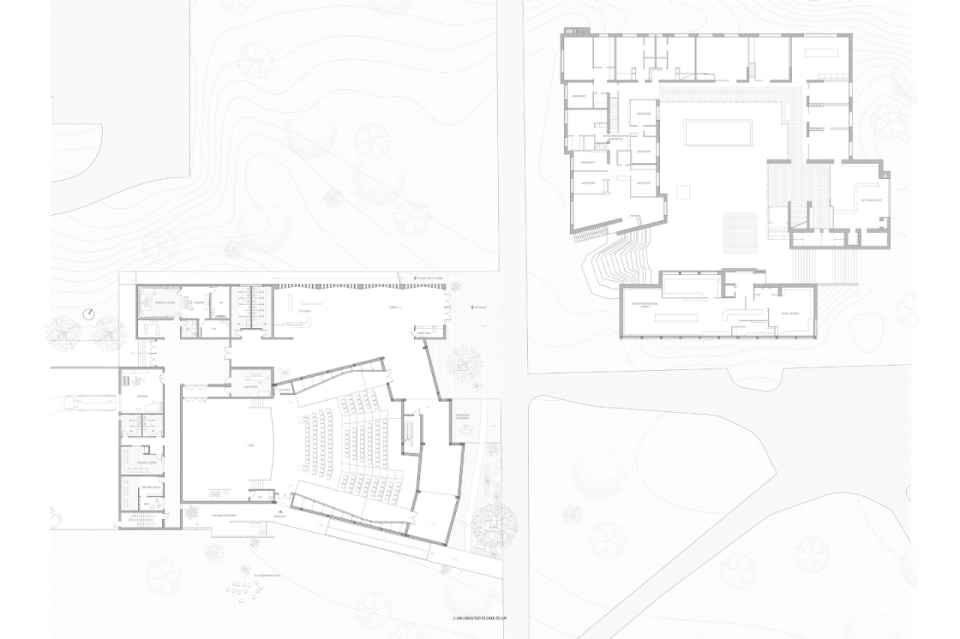

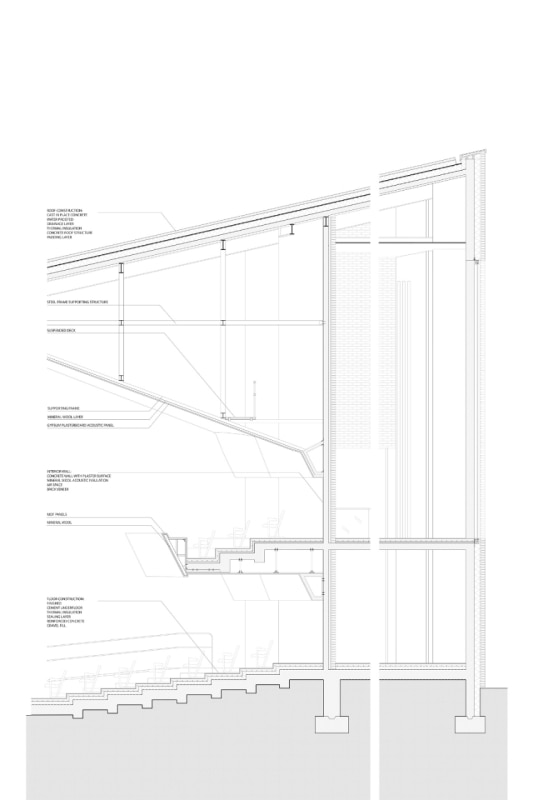

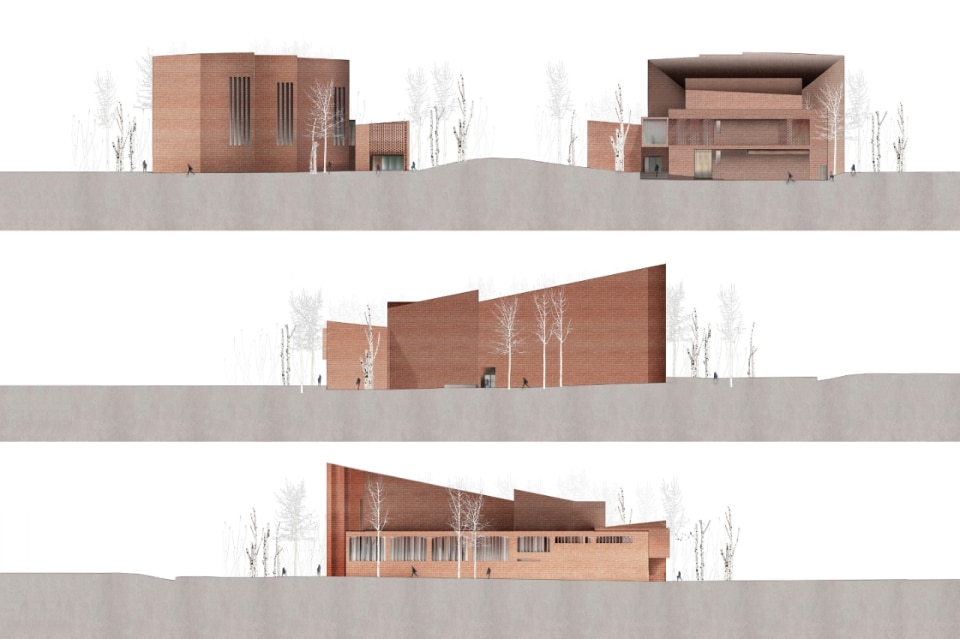

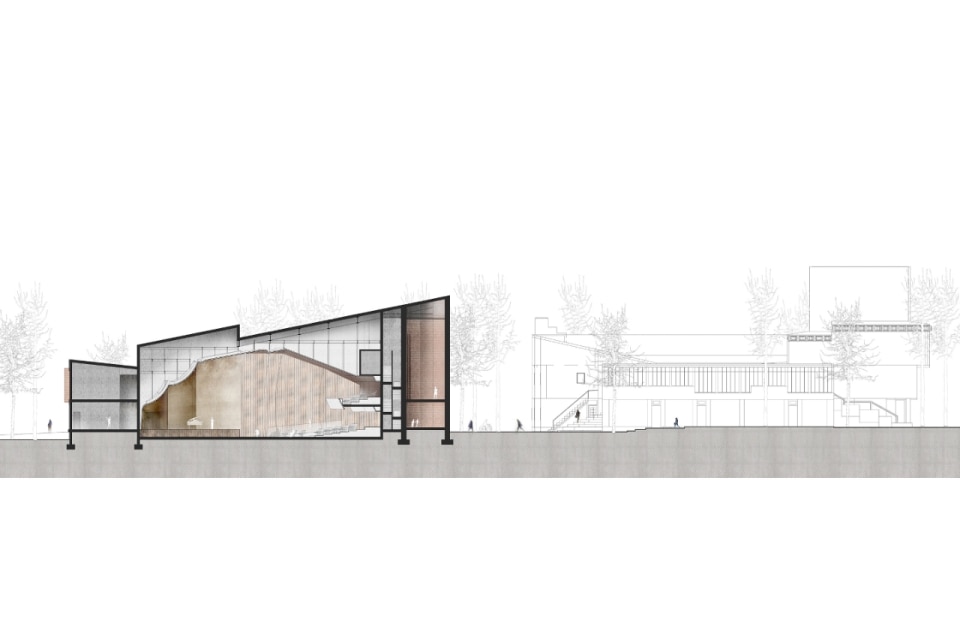

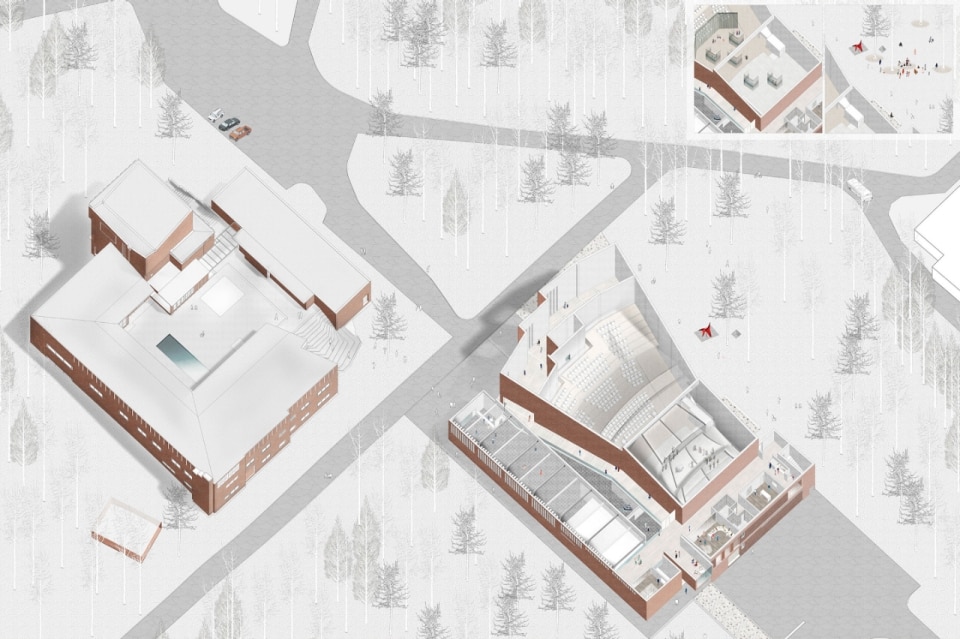

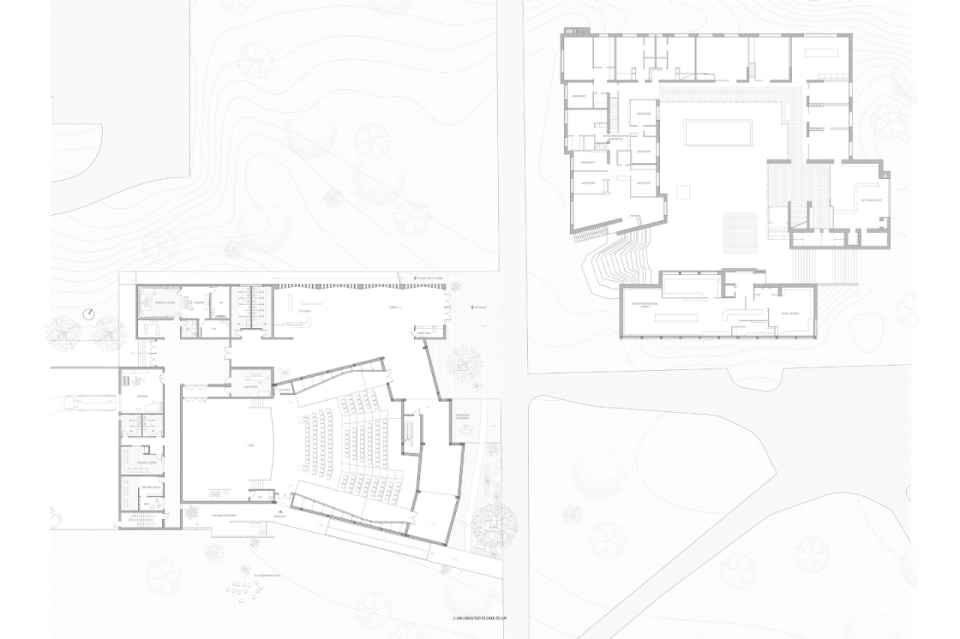

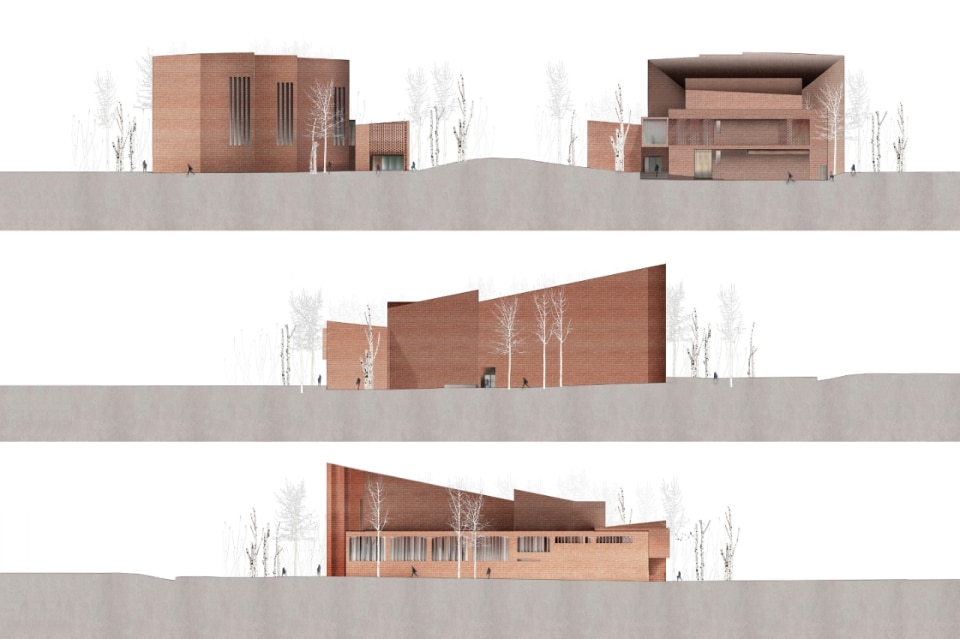

If you’re thinking of a Bilbao effect—an iconic architectural work generating a wave of development—that is not what will likely happen in Säynätsalo. The Light of the North Musical Art Centre, designed by the Chinese firm Chuxin Tuoyuan as part of Harvard’s invitation, “inherits the civic spirit and proportional order of the original complex,” explains Meng Zhao, the studio’s founder, in an interview with Domus.

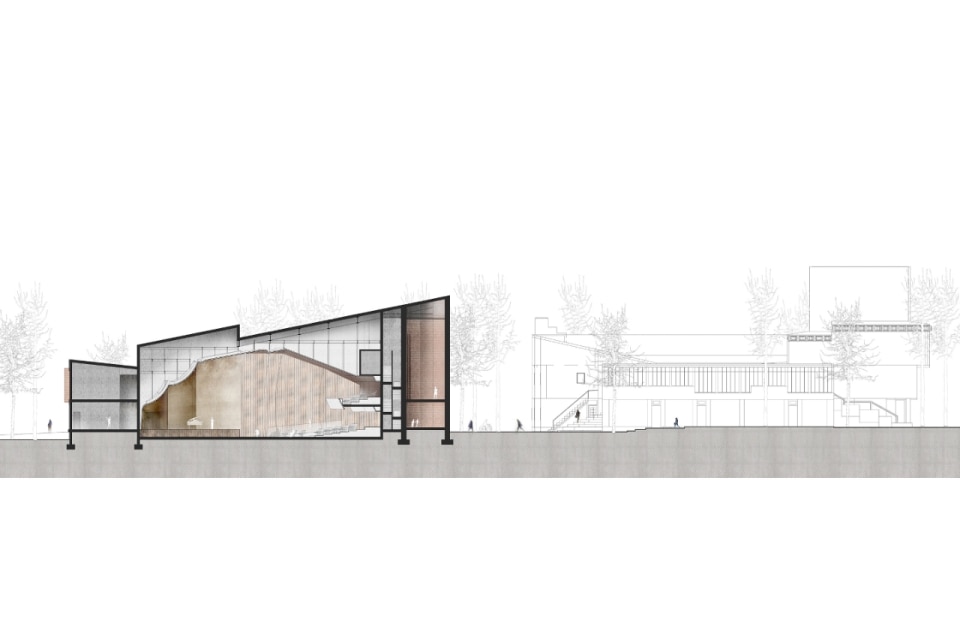

Looking at the project drawings, it is clear that the intervention is anything but disruptive; in fact, what surprises is its direct continuity with the town hall, located across the street.

The language adopted by the Chinese studio is closer to that of the Finnish master in its use of materials than in its layout: while Aalto conceived a complex facing a large elevated courtyard, connected to street level via two opposing staircases of different shapes, the studio led by Meng Zhao focuses on the compactness of the building, while maintaining a degree of permeability precisely in correspondence with Aalto’s “organic” staircase.

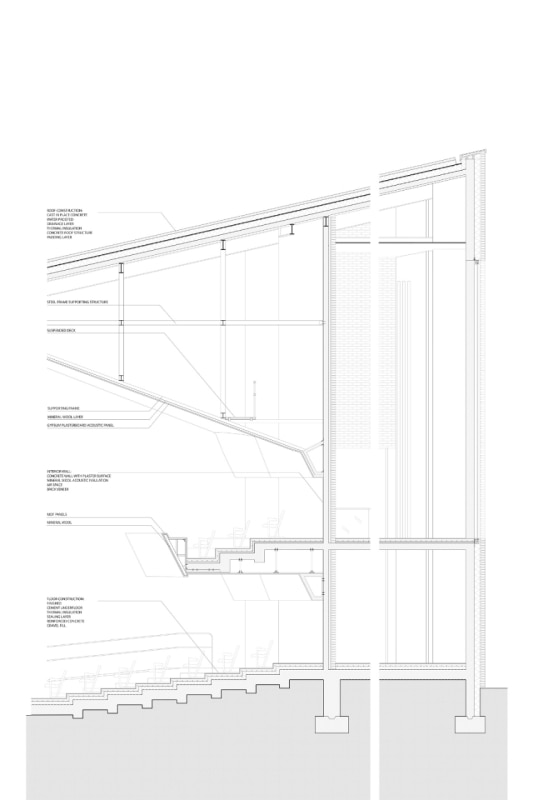

“The rhythmic arrangement of perforated bricks and curved wooden panels aims to create continuity between the existing and the new,” notes Meng Zhao, highlighting the material reference to Aalto’s architecture: the bricks, as well as the curved wood, are direct quotes. The interior space, imagined as both welcoming and contemplative, aims to evoke an atmosphere similar to that of a forest—an operation that Aalto himself carried out, though in different forms, for the Finnish pavilions at the 1937 Paris and 1938–39 New York Expositions.

A lot of Aalto, but not too much

Functionally, the center is designed to “encourage intergenerational participation and address rural depopulation through culture and creativity,” says Meng Zhao. The intention is clear: using culture as a tool for regeneration.

At the same time, it seems that Aalto’s architectural lesson is used to legitimize the intervention itself, which becomes almost a conscious quotation—less an homage than a strategy: blending into the existing framework without disrupting it, speaking the same language to “gain acceptance.”

View gallery

View gallery

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

Chuxintuoyuan, The Light of the North Musical Art Center, Säynätsalo

Courtesy Meng Zhao

If ever built, the Light of the North Musical Art Centre will have to contend with the risk of appearing excessively deferential, an approach that could significantly limit the building’s expressive strength. This is the same issue confronted by the firm A-Konsultit in its expansion of the Alvar Aalto Museum in Jyväskylä. In that case, however, the designers had the advantage—if not the luck—of working with Aalto’s own unrealized ideas, resulting in a project halfway between philological and contemporary.

In the case of the new—and hypothetical—cultural center, one must also consider that in a small, largely rural community like Säynätsalo, visual and symbolic continuity with an architect perceived as a national hero may be precisely what the community needs to recognize itself and perceive change as positive rather than as a break with the past.

Ultimately, more than providing answers, the Chuxin Tuoyuan project brings to the forefront a still-open question for contemporary architecture: how does one build next to the work of a twentieth-century master without becoming trapped by it and without pretending to surpass it?

Opening image: Säynätsalo Town Hall (1949-52). Photo Martti Kapanen, Alvar Aalto Foundation