The category of DIY prefabricated and transportable houses, freed from the dogma of the fixed and permanent architectural object, spread rapidly in America as early as the late 1800s. Although semi-permanent and mobile housing was also produced in 20th-century Europe to address the housing challenges brought on industrial development and since the two world wars, it was in the United States that this mode of living became tied to an ideological, work-related, and cultural revolution expressed above all through nomadism—not only of the individual, but of their home as well.

Caravans, trailers, and mobile homes, as well as prefabricated units transportable by truck, small, low-cost popular dwellings that could be assembled in a few hours and to which major figures in architecture such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Buckminster Fuller and Walter Gropius devoted attention, gradually evolved into a systematic and increasingly sophisticated phenomenon, culminating in the late 1990s with the rise of the Tiny House trend.

The spread of what initially represented a niche interest—some will remember Lloyd Kahn and Jay Schafer, founder of Tumbleweed Tiny House—has led to a varied market in which social needs, aesthetic aspirations, and speculative dimensions coexist. This evolution is symptomatic of how the right to housing has been progressively eroded by commodification dynamics that have profoundly altered its forms and social function. After the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, prefabricated micro-houses emerged again as a topic, perhaps because there is a growing need to identify strategies to respond to a transnational housing emergency with solutions that allow people to exercise autonomy, reduce costs, and reaffirm a relationship with one’s home that differs from the one imposed by the real estate market.

But what happens if Amazon takes over?

Interest is no longer confined only to the United States and Canada, where the use of such dwellings is historically far more widespread and culturally accepted than in Europe. Since they began appearing on online marketplaces a few years ago— initially in their most rudimentary form as metal containers converted into prefabricated homes — Tiny Houses have become the meeting point between a real need and an offer capable of interpreting an aspirational demand: owning a home at prices that are, at least on paper, affordable.

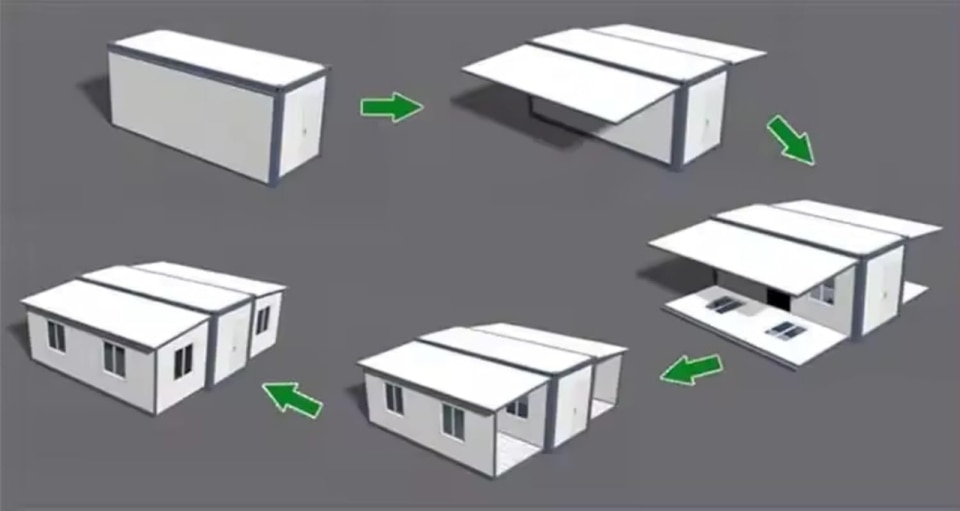

Benefiting from a kind of globalization of imaginaries once geographically limited, today anyone can stumble upon a “Prefab Tiny House Luxury Prefab Container Tiny Home” available for a few thousand dollars with a single click. Amazon’s catalog overflows with modular mini-homes that are versatile, multifunctional, mobile, sustainable, fully customizable, accessorized, and even luxurious; built in wood or metal, thermally insulated, with two, three, or four rooms compacted into just a few square meters, complete bathroom, equipped kitchen, and folding systems that allow the spaces to expand or be designed by sending a message via WhatsApp.

And yet, we are not talking about luxurious prefabricated glamping shelters, nor of design experiments along the lines of modernist existenzminimum, nor of micro author housing models. We do not find Ikea, the start-up Boxabl by Elon Musk, or companies such as the Capsule Castle that promise green-immersed habitats ready to combine a vision of radical living with essential living.

Rather than offering a design concept or truly accessible and sustainable solutions, the Prefab Tiny Homes on Amazon appear as the latest manifestation of the house-as-commodity, the culmination of a commodification process that has not only structurally undermined the right to housing, but has redefined the home as an ordinary consumer good—freely purchasable and deliverable wherever and whenever you want.

Thus, one can scroll through listings promising a “Modern Single Luxury Apartment” made with sustainable, high-quality materials shipped from who-knows-where; sellers with nonexistent names guaranteeing 10-day delivery and 10-minute assembly for multifunctional two-story prefab homes priced between 7.000 and 60.000 dollars. If at first the trend centered on repurposed shipping containers — alongside the offer of DIY wooden houses sold in assembly kits — now the market includes custom modifications, different layouts, and varied finishes for dwellings that sometimes show no consistency with the sales details (or even the product description).

One of the most visible channels through which both enthusiasm and skepticism toward Amazon’s new prefabricated homes—promising more and more under unclear conditions—can be observed is YouTube, where numerous videos thoroughly debunk the platform’s listings. Some focus on the possible lack of compliance with local building regulations, others on customs and shipping fees; some read the reviews available on Amazon— very few —and a small minority even perform live unboxings of their purchase.

The most common advice, though contrary to the many articles that periodically proclaim a global revolution of “buying a house with a click,” is not to give in to Amazon’s insistent algorithm, but to purchase directly from the suppliers and wisely lower one’s expectations. After all, there is still no significant and reliable data that precisely quantifies the total number of buyers on a global—or even national—scale. For now, the market remains primarily American, and the uncertainties surrounding regulations and permits make direct purchasing far less practical than media narratives suggest.

The popularity of this phenomenon brings into focus several unresolved questions about the future of our housing conditions and the paradoxical forms they may take in an era of increasing privatization and precarity. In the case of Tiny Homes sold on Amazon, need and solution risk feeding one another in a vicious cycle, because it is difficult for an individual market action—the independent purchase of a micro-home on an e-commerce platform—to correspond to the claim of a right that is, by nature, social and collective.

Why, then, this tendency to turn to Amazon to compensate for our lack of control over contemporary living? Perhaps simply because it offers us the illusion therof, along with the thrill of being able to choose among countless options and possible ways of life. But one thing is certain: if a company like Amazon is dispensing housing solutions with a click—and it begins to seem like a plausible remedy—then the time has come to ask what this phenomenon is truly a symptom of.