During the first major snowstorm of the New York winter, newly elected mayor Zohran Mamdani didn’t just appear behind a podium. He addressed citizens urging them to stay home and read Heated Rivalry, the novel behind the most talked-about series of the moment.

He did so wearing a Carhartt jacket — a Full Swing Steel model genuinely built for the cold — purchased at Dave’s New York, a long-standing workwear and uniform store in Chelsea, and later customized by Brooklyn-based embroidery company Arena Embroidery, under the close supervision of the mayor’s team.

Just hours later, the same jacket was with him as he shoveled snow in neighborhoods across the city.

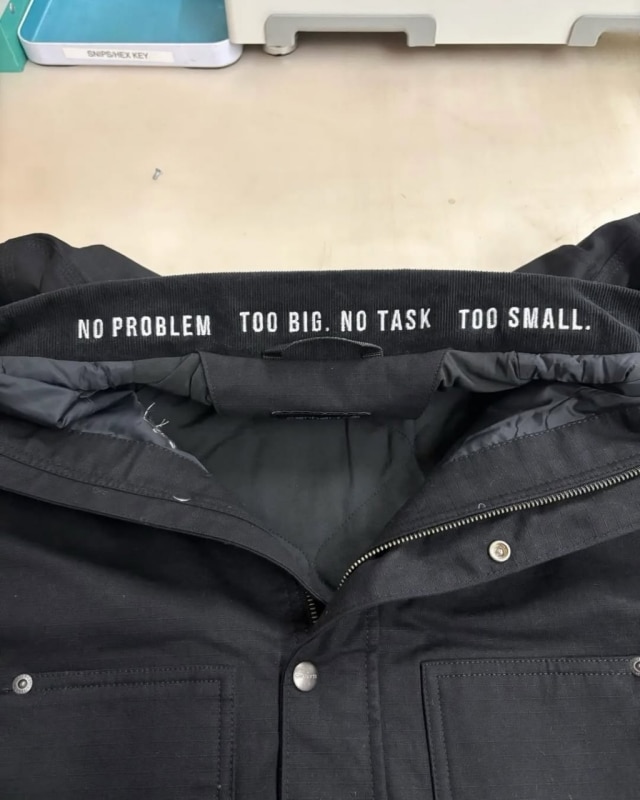

This custom piece, which has sparked widespread conversation in recent hours, had every reason to stand out — especially given the symbolic weight of the choice. On the chest, in place of a traditional logo, the words “The City of New York” appear, treated like an institutional brand but without graphic emphasis. On the left bicep, in bold lettering, the word “Mayor.” Inside the collar — hidden and therefore readable only by the wearer — is a phrase Mamdani himself spoke in the first hours after his electoral victory: “No problem too big, no task too small.”

Not a campaign slogan, not a call to action, but a statement of posture — almost a private reminder turned sartorial detail. The result is not political merchandising (there is no intention of mass reproduction or consumer appeal) but the conscious construction of a unique object that uses the language of clothing to express an idea of power that is operational, present, and not detached from work.

It is not political merchandising, but the conscious construction of a unique object that uses the language of clothing to articulate an idea of operational power.

Because in the United States, Carhartt is not a neutral brand — and above all, it is not interchangeable. It is workwear in the most literal sense: clothing for labor, construction sites, physical effort. Founded in Detroit in the late nineteenth century, the company grew by supplying overalls, jackets, and uniforms to workers, railroad employees, soldiers, and women employed in factories during World War II.

At this point, it becomes essential to clearly distinguish Carhartt USA from Carhartt WIP — the European, fashion-oriented branch of the brand, launched in the 1990s and gradually absorbed into global streetwear circuits. In Europe, Carhartt is often associated with urban subcultures, fashion collaborations, and stylistic reinterpretations of workwear heritage. In the United States, however, it remains tied to a blue-collar, practical, functional imaginary. Mamdani’s choice is meant to speak precisely this language.

This is not the first time workwear has entered the wardrobe of American Democratic politics. Precisely because it is rooted in ideas of labor and function, Carhartt has over the years become a visual code used to signal a certain proximity — real or aspirational — to the working class. It is not anti-aesthetic; rather, it is an aesthetic that rejects ornament in favor of credibility.

The great sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, in Distinction, explained how taste, culture, and power are never individual matters, but tools through which social hierarchies become visible and are reproduced. In today’s media landscape, this insight feels almost prophetic. Aesthetics has become one of the main symbolic battlegrounds of politics, often dominated by the right — think of Melania Trump, Nancy Reagan, or the Berlusconi family — who have used image as a promise of order, success, and authority, often reducing it to pure status.

And yet, at least in this respect, the United States can offer a different example, where style and aesthetics can also function as progressive tools. Since the Kennedy era, clothing has often worked as a coherent extension of political vision, and that tradition survives today in figures capable of using image with awareness, without letting it overshadow the message: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rawa Duwaji, New York’s young first lady, Mamdani himself, and Michelle Obama, who recently wore a Chanel look while presenting her book The Look, a photographic exploration of her own style.

The comparison with Italy, at this point, becomes inevitable. Here, fashion is still often perceived — especially by parts of the political class — as a frivolous or ideologically suspect territory. The left has frequently chosen to withdraw from the field of image, confusing aesthetics with luxury and thus giving up one of the most silent yet powerful political tools. And when someone does turn to an image consultant, they are quickly condemned for superficiality, as the Schlein case illustrates. The result is a form of symbolic marginalization with nothing virtuous about it.

In this sense, Mamdani’s jacket works as a reminder. It shows that aesthetics is not an optional extra, but a fully fledged political language.

And perhaps it is also a signal: we need to start building an image of power that is coherent, legible, and, when necessary, willing to get its hands dirty.