“A flexible space,” is how Carlo Antonelli describes it, but also “a spaceship” and “a monstrous sound machine.” “This space is a device,” echoes Giorgio Di Salvo, who curated the audio and acoustic project together with Lucio Visintini, with technical support from the company Knauf. Antonelli developed the concept of Voce in his role as the project’s scientific advisor, envisioning it as a space for listening and hosting immaterial creative projects.

Voce is Triennale’s new space dedicated to sound, located on the “park level” of the Palazzo dell’Arte—the same level that hosts the theater and opens onto the gardens. Voce is not a club, not a concert venue, not a music production studio, nor an audio content hub (podcasts included). At the same time, it is all of these things.

Stefano Boeri, president of Triennale, presents it as a place that “could become a gallery where unique musical works are collected, accessible only here.” Boeri also emphasizes the symbolic value of the new project, as it demonstrates that “public institutions can do high-quality things.” Voce is therefore not just a performance space: it will host a collection of new, site-specific musical works, available exclusively within it—just like a painting in a museum.

Carlo Antonelli repeatedly highlights the sonic aspect during a presentation ahead of the public opening—scheduled for May 13—which coincides with the inauguration of the upcoming International Exhibition. “We’ve spent twenty years listening through phones,” he says. Voce aims to rediscover the complexity and physicality of sound thanks to its impressive soundwall: an immersive system capable of distributing audio in a diffuse way—unseen yet visually striking—integrated into more than 300 square meters of space.

“A giant brain wrapped in kilometers of cables,” Antonelli explains. The space was designed as a sound machine, where every element contributes to the listening experience.

The lighting is by Anonima Luci, using a pixel-to-pixel digital LED system stretching 350 linear meters and over 8 kilometers of wiring. A luminous scanning of the space, working in sections, present in its most abstract and nearly invisible form.

The seating, designed by Philippe Malouin and produced by Meritalia, is green and curved—modular felt elements with visible stitching, inspired by sound waves. In the room that hosts Voce, overlooking the garden (which in summer will feature an event stage), the original structure of Giovanni Muzio’s building has been revealed, with its grid of pillars and asymmetrical aisles.

Until a few months ago, this space housed Old Fashion. Before that, the legendary Piper (where Jimi Hendrix also played—and stayed for a while in Milan), and even earlier, the RAI radio studios, audio counterparts to the TV studios now occupied by Triennale’s theater.

“People were already dancing here in 1933,” says architect Luca Cipelletti, who designed the architecture and layout. The environment has been fully acoustically isolated from the rest of the building, thanks to laminated wood panels that conceal empty cavities and a sophisticated ceiling treatment.

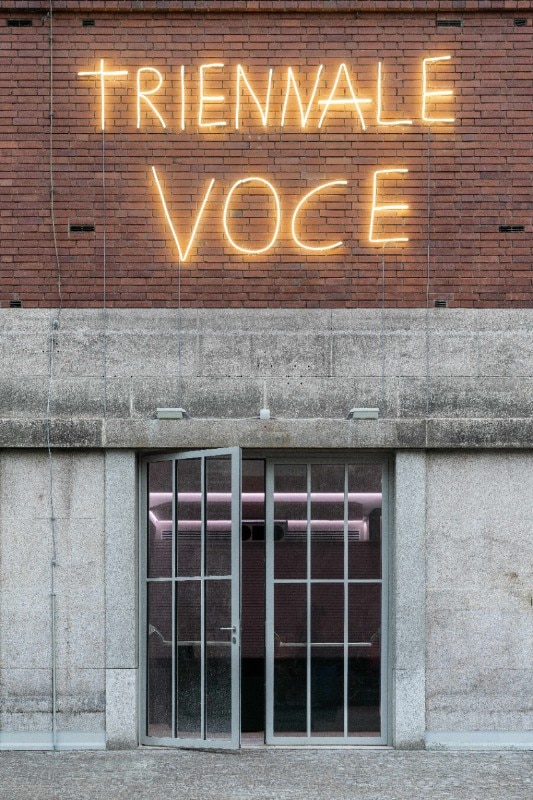

For the first month, Voce will also be open during the day, from 10:30 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. After that, regular hours will be 6:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m., Tuesday through Sunday. A cocktail bar run by T’a Milano will be active in the space, with a drink list curated by Daniel dell’Olio. Among the first scheduled events is a sold-out concert by Beth Gibbons of Portishead, along with many other Italian and international guests. On the façade that marks Voce’s entrance, artist Marcello Maloberti has installed the light piece Triennale Voce—a white neon sign in his own handwriting that emphasizes the value of orality as an artistic and poetic form.

Opening image: Voce, Triennale Milano 2025. Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani. Courtesy Dsl Studio