In recent years, a parallel and almost invisible real-estate market has taken shape: that of private high-security shelters, conceived not only to offer protection in extreme situations but to guarantee luxury, exclusivity, and the full spectrum of ambitions that define a certain lifestyle.

It is not an extension of survivalism, but an architectural grammar that merges innovation, systemic fears, and wellbeing experiences translated into habitat.

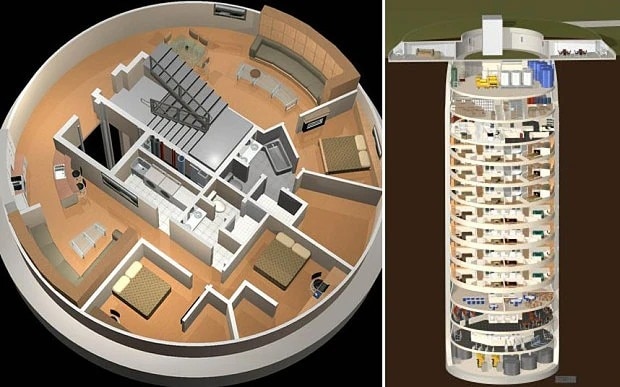

From missile to underground condominium

One example is Raven Ridge 11, part of the American complex Survival Condo, carved out of an old Atlas missile silo in Kansas: 15 underground floors with a swimming pool, hydroponic greenhouse, theater, library, climbing wall, bar, and even detention cells, a decontamination room, and a sniper post.

The units, sold at figures that some estimates place in the millions of dollars, represent an architecture of security disguised as a residential community.

Aerie: the 300-million therapeutic enclave

Even more exclusive is Aerie, the 300-million-dollar project developed by SAFE and announced for 2026: an underground club for 625 members, each equipped with a suite that can be modeled as a private residence—up to 20,000 square feet—immersed in an ecosystem of indoor pools, fine-dining restaurants, AI-assisted medical centers, and longevity-oriented facilities.

Not a simple bunker, but a therapeutic enclave designed for a community that imagines survival as an extension of wellbeing.

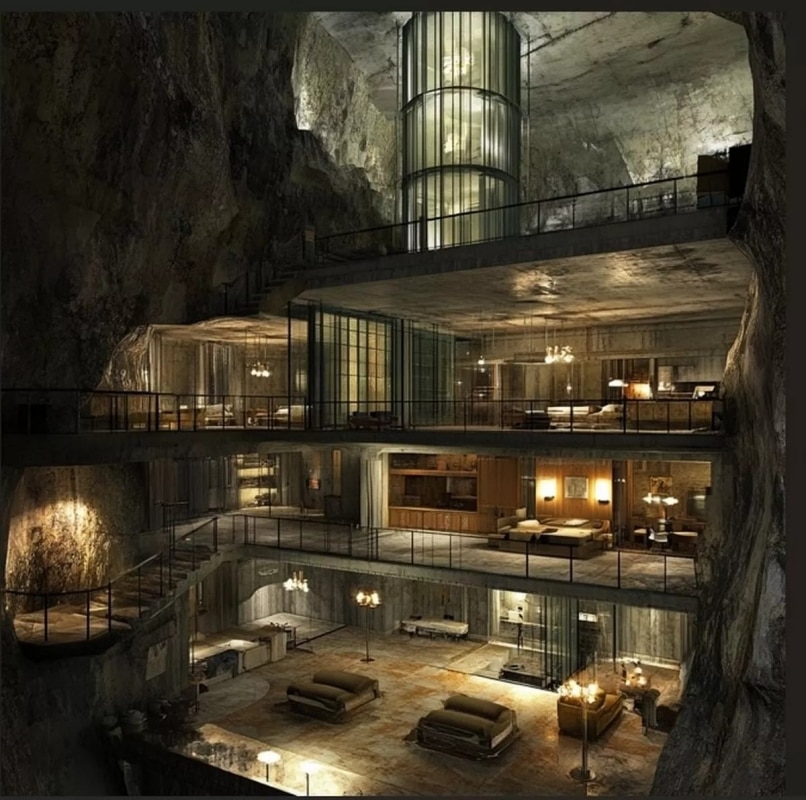

The Oppidum: an underground palace in Central Europe

In Central Europe, the Oppidum in the Czech Republic is among the most radical attempts to transform the underground into high-end residential architecture. Originally conceived as a Soviet-era security structure, today it is an underground palace with a surprisingly rich spatial articulation: suites shaped according to the grammar of luxury hospitality, an interior garden with a calibrated light cycle, and scenographic rooms with digital “windows” simulating impossible horizons.

@bryson_owen Things that make sense in a bunker! #surviavlbunker #survivalcondo #bunker #bunkers #doomsday #doomsdaypreppers #undergroundbunker #luxurybunkers #luxurybunker #buildabunker #bunkerlife #bunkerboy #warbunker #survivaltips #bunkergear #secretbunker #doomsday #doomsdaymom #doomsdayevent #familybunker #mrbeast ♬ original sound - Bryson Owen

The sequence of spas, cinemas, and armored wine cellars translates the aesthetics of the shelter into a language of absolute comfort. Here, the bunker merges with the elite residence, aiming not so much at survival as at the continuity of privilege under extreme conditions.

Vivos: the global infrastructure of the day after

Responding to the same ambition is the network of underground shelters built and managed by Vivos, led by CEO Robert Vicino and active for over a decade. It includes at least three major complexes: xPoint in South Dakota (575 bunkers for thousands of people), a shelter in Indiana, and the massive Europa One in Germany.

Described as “the ultimate escape from doomsday,” Europa One—excavated into the karst rock of Thuringia—features an armored infrastructure designed to withstand nuclear explosions, chemical agents, and extreme events. Private quarters finished with noble materials stand alongside theaters, underground greenhouses, and collective spaces organized as a small autonomous settlement.

Luxury troglodytism

At first glance, these bunkers may seem like the extreme expression of private protection. In reality, the super-rich are colonizing not only the vertical space of skyscrapers but also the urban underground through what some define as a form of “luxury troglodytism”: monumental basements, defensive residences, and armored structures configured as devices of privilege.

The subterranean secession

The race for luxury shelters signals a shift in the psychology of power: elites no longer perceive themselves as guarantors of social stability but as subjects who must withdraw from the world they have contributed—both for better and for worse—to shaping.

It is a dynamic that recalls what sociology—starting with Michael Hechter—defines as a form of “secession of the rich”: privileged groups carving out separate physical and symbolic spaces in order to preserve living conditions no longer guaranteed in the common sphere.

The right to safety

What may seem like an architectural absurdity opens up a larger question: who will have the right to be safe?

View gallery

View gallery

RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon, Bunker 599, Diefdijk, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2013

One of the 700 bunkers of the New Dutch Waterline (NDW), a military defence line in use from 1815 to 1940 that protected the cities of Muiden, Utrecht, Vreeswijk and Gorinchem by deliberate flooding, becomes a striking public attraction thanks to a radical design gesture that aims to promote a naturalistically and historically significant area for the country. The small, seemingly inaccessible bunker is ripped in half by a wooden pathway that reveals the interior of the building, which is generally precluded from view, and leads visitors to the paths of the adjacent nature reserve.

Photo Holland-PhotostockNL from AdobeStock

RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon, Bunker 599, Diefdijk, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2013

Photo Holland-PhotostockNL from AdobeStock

B-ILD, Bunker pavilion, Vuren, The Netherlands 2014

An underground bunker is renovated to make the best possible use of the minimal interior space (9 square metres of floor area by two metres in height) and converted into a holiday home. The floor plan is reproduced above ground through a platform that serves as a terrace.

Photo Tim Van de Velde

L+, Grüner St. Pauli, Hamburg, Germany 2015

A multi-storey bunker from 1942, which housed up to 25,000 people during the bombing of Hamburg, is being given a new lease of life through a conversion project aimed at preserving the building's memory and enhancing its attractiveness. The addition of several storeys made it possible to create new planted terraced spaces culminating in a public park at the top. The building also houses a hotel, commercial, recreational and training spaces.

Photo Felix Geringswald from AdobeStock

Sammlung Boros, Berlin, Germany 2017

In the district of Mitte, a bunker erected in 1942 as an air-raid shelter for the civilian population, later becoming a fruit store during the DDR and finally a Mecca for techno ravers now houses the Boros Collection, a private collection of contemporary art comprising groups of works by international artists from 1990 to the present day, displayed in the over 3,000 square metres of exhibition space.

Photo Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from wikimedia commons

BIG, Tirpitz Museum, Blåvand, Denmark 2017

BIG's intervention expands and transforms a hermetic concrete bunker from World War II into a cultural complex perfectly integrated with the listed landscape of Blåvand in western Denmark. The building, totally hidden in the landscape, consists of a single 2,800 square metre structure with four exhibition spaces excavated in the earth and marked on the surface by a series of cuts in the hillside that lead into the heart of the museum.

Photo Siegbert Brey from Wikipedia

Ateljé Ö, Bunker 319, Gotland, Sweden 2021

The project extends a Cold War bunker, located in a hilly area overlooking the Baltic Sea, for housing purposes. In addition to the bunker, the complex includes four new low houses set around an inner courtyard in which a tree stands, evoking the idea of a small village square. Rough, natural materials such as exposed concrete and wood in the shells and local gravel in the roofing blend the rigorous volumes into the natural landscape.

Photo Martin Brusewitz

Archea Associati, Digital Shelter, Florence, Italy 2022

The refurbishment of an old anti-aircraft tunnel is part of a redevelopment programme for an area of Florence not popular with tourists. The construction, which creeps 33 metres into the hill under Piazzale Michelangelo, designed in 1943 as a place of defence against World War II bombing by exploiting an older drainage system, has been recovered by Archea Associati as an art gallery devoted to digital research. With a total area of 165 square metres, the heart of Rifugio Digitale is the tunnel with 16 screens hosting temporary exhibitions, events and performances on art, architecture, photography, literature and cinema.

Photo Pietro Savorelli Associati

Archea Associati, Digital Shelter, Florence, Italy 2022

Photo Pietro Savorelli Associati

Corstorphine & Wright, The Transmitter Bunker, Dorset, UK 2023

The Bunker, which was used during the Second World War as part of the "Chain Home" radar system to detect enemy aircraft and signal their position, is set in a spectacular landscape context that led the owners to transform the military building into a holiday home. The reuse was intended to preserve as much as possible of the brutalist spirit of the space. From the entrance, underground as in its origins, the interior space opens onto Ringstead Bay with a large window that introjects light. The exposed concrete shells have been meticulously preserved, insulated and waterproofed from the outside to avoid distortion. The high thermal mass produced by the earth covering the building minimises the need for energy to heat the spaces.

Photo Will Scott

RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon, Bunker 599, Diefdijk, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2013

One of the 700 bunkers of the New Dutch Waterline (NDW), a military defence line in use from 1815 to 1940 that protected the cities of Muiden, Utrecht, Vreeswijk and Gorinchem by deliberate flooding, becomes a striking public attraction thanks to a radical design gesture that aims to promote a naturalistically and historically significant area for the country. The small, seemingly inaccessible bunker is ripped in half by a wooden pathway that reveals the interior of the building, which is generally precluded from view, and leads visitors to the paths of the adjacent nature reserve.

Photo Holland-PhotostockNL from AdobeStock

RAAAF and Atelier de Lyon, Bunker 599, Diefdijk, Utrecht, The Netherlands 2013

Photo Holland-PhotostockNL from AdobeStock

B-ILD, Bunker pavilion, Vuren, The Netherlands 2014

An underground bunker is renovated to make the best possible use of the minimal interior space (9 square metres of floor area by two metres in height) and converted into a holiday home. The floor plan is reproduced above ground through a platform that serves as a terrace.

Photo Tim Van de Velde

L+, Grüner St. Pauli, Hamburg, Germany 2015

A multi-storey bunker from 1942, which housed up to 25,000 people during the bombing of Hamburg, is being given a new lease of life through a conversion project aimed at preserving the building's memory and enhancing its attractiveness. The addition of several storeys made it possible to create new planted terraced spaces culminating in a public park at the top. The building also houses a hotel, commercial, recreational and training spaces.

Photo Felix Geringswald from AdobeStock

Sammlung Boros, Berlin, Germany 2017

In the district of Mitte, a bunker erected in 1942 as an air-raid shelter for the civilian population, later becoming a fruit store during the DDR and finally a Mecca for techno ravers now houses the Boros Collection, a private collection of contemporary art comprising groups of works by international artists from 1990 to the present day, displayed in the over 3,000 square metres of exhibition space.

Photo Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from wikimedia commons

BIG, Tirpitz Museum, Blåvand, Denmark 2017

BIG's intervention expands and transforms a hermetic concrete bunker from World War II into a cultural complex perfectly integrated with the listed landscape of Blåvand in western Denmark. The building, totally hidden in the landscape, consists of a single 2,800 square metre structure with four exhibition spaces excavated in the earth and marked on the surface by a series of cuts in the hillside that lead into the heart of the museum.

Photo Siegbert Brey from Wikipedia

Ateljé Ö, Bunker 319, Gotland, Sweden 2021

The project extends a Cold War bunker, located in a hilly area overlooking the Baltic Sea, for housing purposes. In addition to the bunker, the complex includes four new low houses set around an inner courtyard in which a tree stands, evoking the idea of a small village square. Rough, natural materials such as exposed concrete and wood in the shells and local gravel in the roofing blend the rigorous volumes into the natural landscape.

Photo Martin Brusewitz

Archea Associati, Digital Shelter, Florence, Italy 2022

The refurbishment of an old anti-aircraft tunnel is part of a redevelopment programme for an area of Florence not popular with tourists. The construction, which creeps 33 metres into the hill under Piazzale Michelangelo, designed in 1943 as a place of defence against World War II bombing by exploiting an older drainage system, has been recovered by Archea Associati as an art gallery devoted to digital research. With a total area of 165 square metres, the heart of Rifugio Digitale is the tunnel with 16 screens hosting temporary exhibitions, events and performances on art, architecture, photography, literature and cinema.

Photo Pietro Savorelli Associati

Archea Associati, Digital Shelter, Florence, Italy 2022

Photo Pietro Savorelli Associati

Corstorphine & Wright, The Transmitter Bunker, Dorset, UK 2023

The Bunker, which was used during the Second World War as part of the "Chain Home" radar system to detect enemy aircraft and signal their position, is set in a spectacular landscape context that led the owners to transform the military building into a holiday home. The reuse was intended to preserve as much as possible of the brutalist spirit of the space. From the entrance, underground as in its origins, the interior space opens onto Ringstead Bay with a large window that introjects light. The exposed concrete shells have been meticulously preserved, insulated and waterproofed from the outside to avoid distortion. The high thermal mass produced by the earth covering the building minimises the need for energy to heat the spaces.

Photo Will Scott

These architectures materialize a radical inequality—spatial segregation that does not simply aim to hide, but to guarantee the continuity of life for a few.

Here, salvation is no longer a shared good: it is a purchasable service, and one that only a few can afford.

Opening image: The Aerie underground club. Courtesy Aerie