The towering silhouette of Battersea Power Station has been a dominant character in London’s industrial, architectural and pop cultural history for almost nine decades. Its finessed Art Deco lines, stoic proportions, and elegant contrast of red brick and white tapering concrete chimneys made it one of the first industrial buildings to capture the imagination of the London urbanite—a building so commanding that it moved beyond its original function to become a cultural icon.

The station has served as a literal and cultural source of energy since it was designed by Giles Gilbert Scott in 1929. By the 1950s, Battersea’s coal-fired energy powered a fifth of London’s electricity demand. It was decommissioned thirty years later, but its visual imprint remained unchallenged—its memorable symmetry and civic presence becoming a backdrop for musicians, artists, film and TV makers; a visual protagonist romanticised by its very disuse.

The station was listed by the National Heritage List for England in 1980 and was closed three years later. From that point, it began its journey through a volley of investors and investment ideas—including one as a theme park—until finally being acquired in 2012 by a Malaysian consortium. With assurance of financial stability, the station’s restoration began, becoming part of one of London’s largest and highest-valued regeneration schemes.

Visiting today, the Battersea Power Station—which was retrofitted by WilkinsonEyre following a winning design proposal in 2013—sits encased within the density of Rafael Viñoly’s wider masterplan: a smorgasbord of ‘starchitectural’ blocks that undulate and caress the edges of the rectilinear station. Ascending the exit steps from the (purposefully extended) Northern line Tube onto Prospect Way, Frank Gehry's deconstructivist cluster of residential buildings—his first in the UK—obscure direct views to the Art Deco station. It peeks out gradually, its red masonry nudging through Gehry’s jagged edges. The approach then leads to a sunken pit of turfed grass, where a handful of picnic benches are strewn across this diminutive plaza, underwhelmingly fronting the majestic façade of the restored industrial giant.

The towering silhouette of Battersea Power Station has been a dominant character in London’s industrial, architectural and pop cultural history for almost nine decades —a building so commanding that it moved beyond its original function to become a cultural icon.

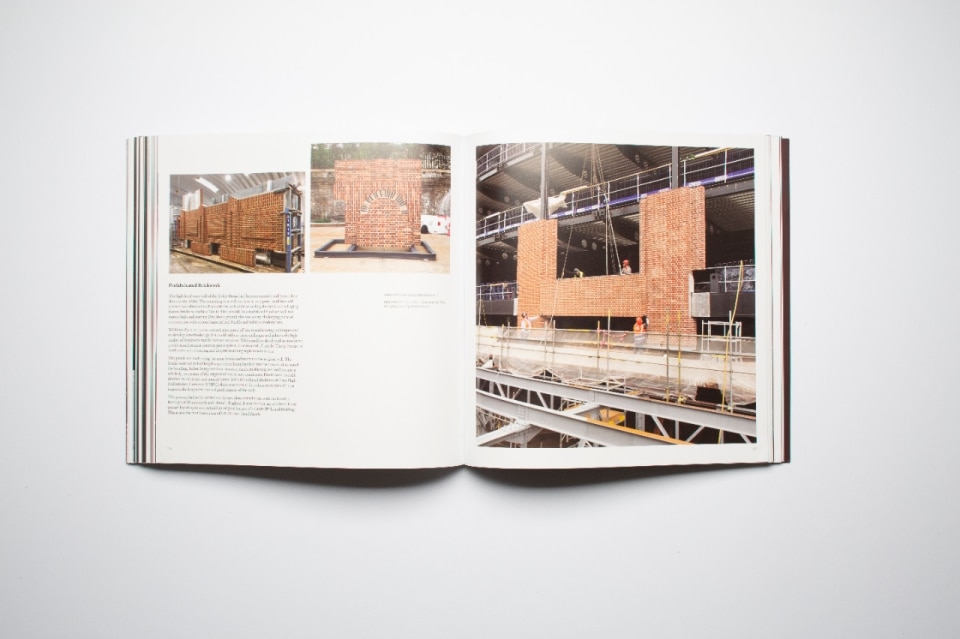

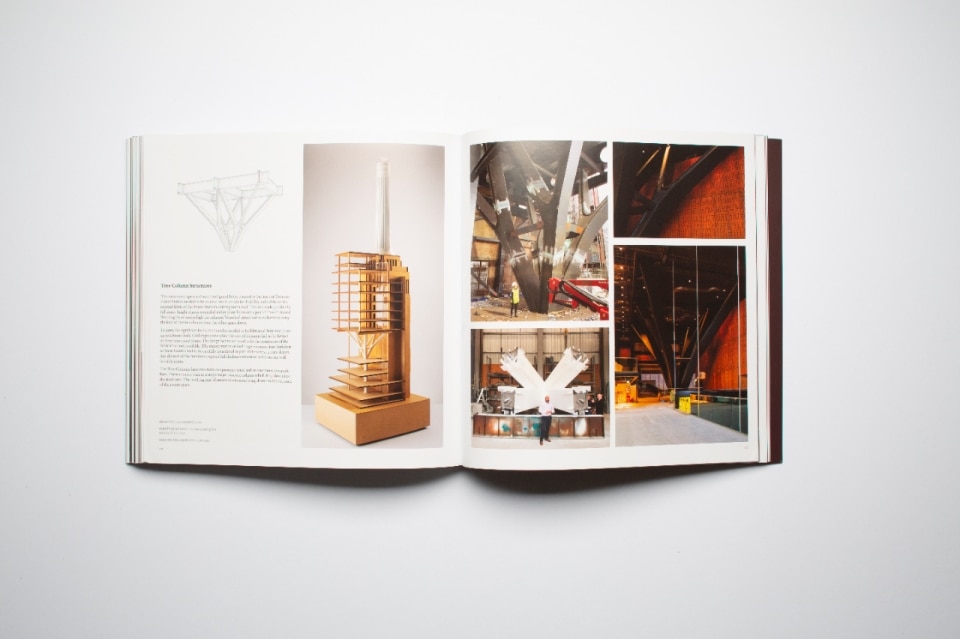

Inside, WilkinsonEyre’s work is a balance of exposure and intervention. In their forthcoming book chronicling work on the project, they describe the importance of maintaining the station’s “scale and visual drama”—an approach they saw as akin to working with “a modern ruin”. Their shared intention with the project client, the Battersea Power Station Development Company, was to retain legibility of all original fabric—to intervene with lightweight form, and to embark on a detailed restoration exercise that reinstated original equipment as urban sculpture. They began with a deep evaluation phase, including a 3D cloud survey of the building and ‘journalistic catalogue’ that formed the basis of their technical and material strategy.

As a result, the station’s native interiors are fully legible—their scale and heft readable against the finely inserted layers of circulation. So calculable are the proportions of the space, that when inside it is easy to imagine the churning sound and heat of the coal-fired engines that once inhabited the hall. Instead, it is now occupied by a programme of retail, event space, and multiplex cinema, with office and residential spaces existing out of sight, beyond the public heart of the building.

The contrast of the pristinely conserved power station against the swathes of new masterplan development that surrounds it is significant. Despite WilkinsonEyre likening the converted power station to a “Town in a City”, the analogy is closer to an upwardly stacked high-street (it is filled with mainly clothes and food), comprising retail units hospitable only to some.

Battersea Power Station has been painstakingly restored and retrofitted with an aim for its original spirit to emanate across time as well as space. But although its character can be fully read and felt, the surroundings in which it is set—swathes of commercial luxury and residential real estate that stands at over twenty times the average London salary—render it untouchable to many: a vintage gem inside a largely impenetrable vitrine.

As an exemplar of sensitive restoration and adaptation, two years on, the station stands proud. As an emblem of urban regeneration, it represents a question tied to many of London’s regeneration sites, particularly those that re-purpose heritage: can cultural identity remain accessible and relatable to all once the function and people it serves is so radically changed?

Opening image: © Peter Landers