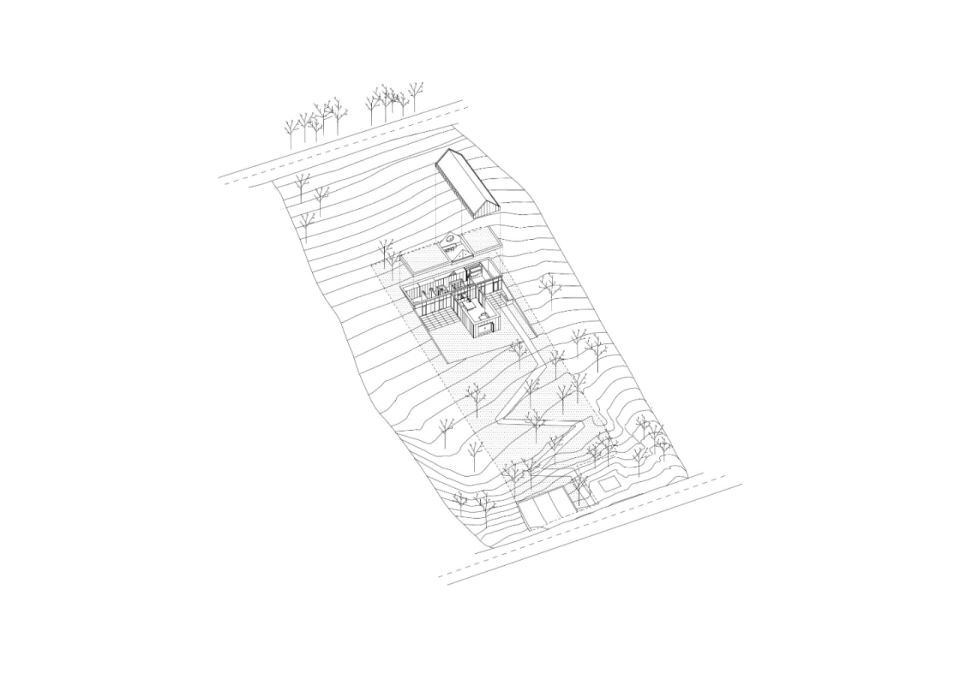

When a client asked for a home on the hills of Lozorno, Slovakia, one that could frame views of the lake below and its verdant setting, the response from Noiz Architekti proved even more site-specific than the request itself, yet deliberately infused with an element of surprise.

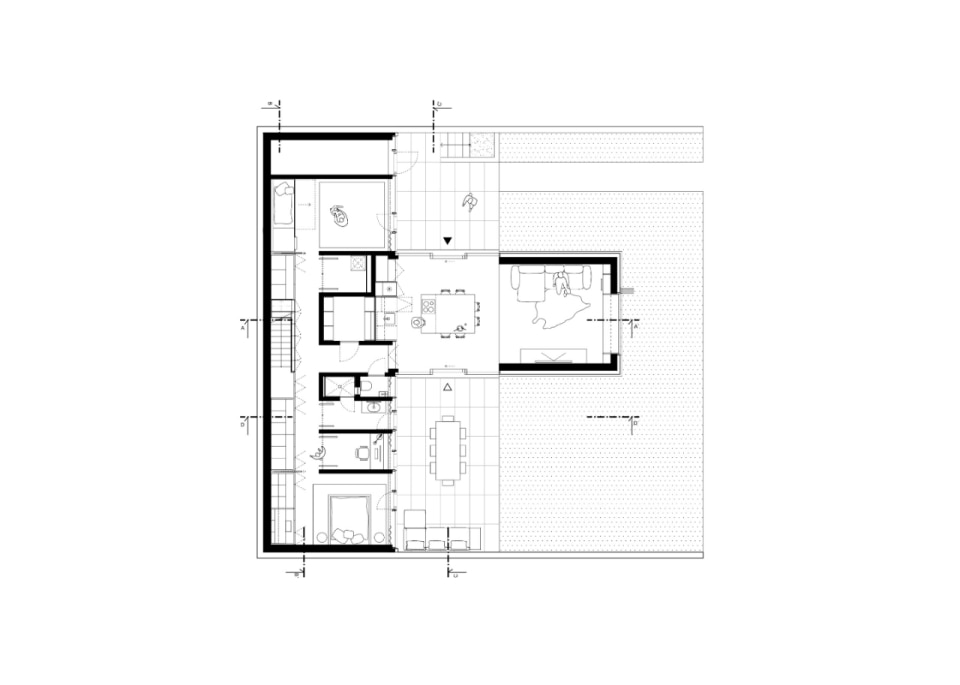

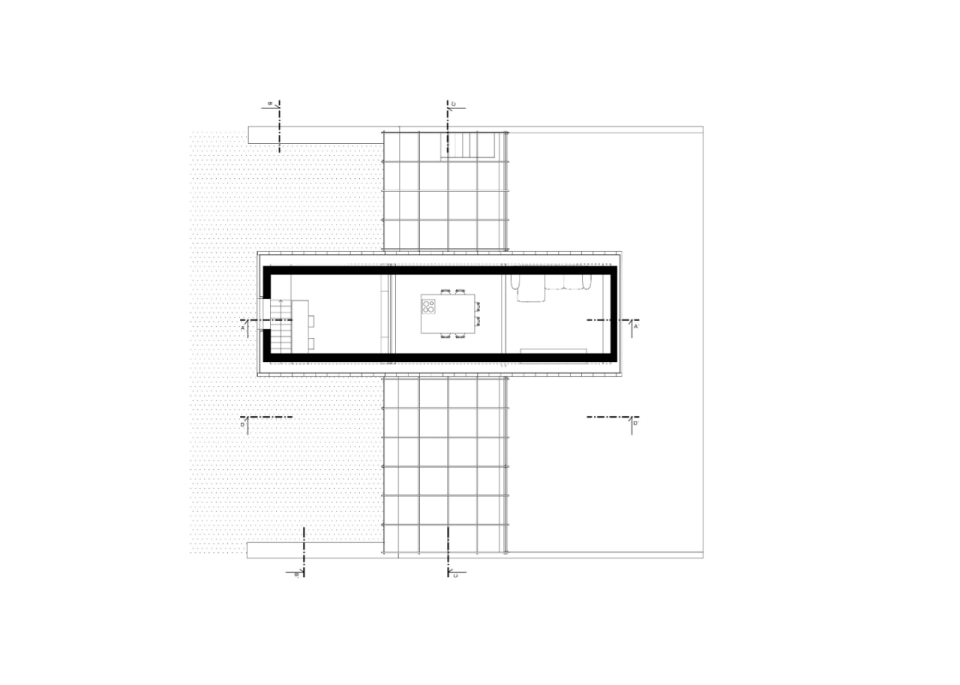

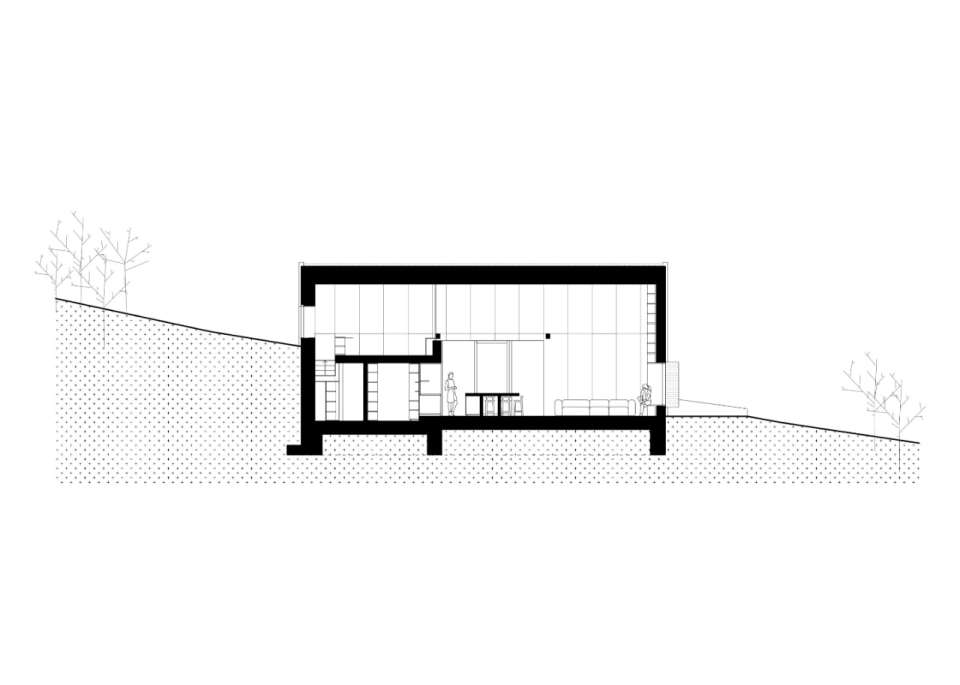

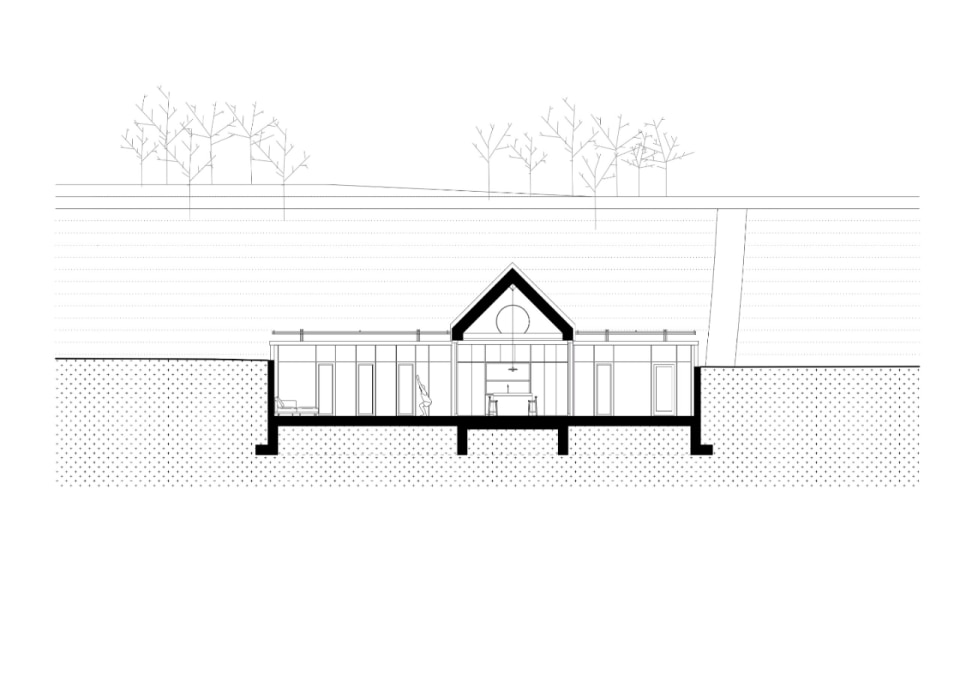

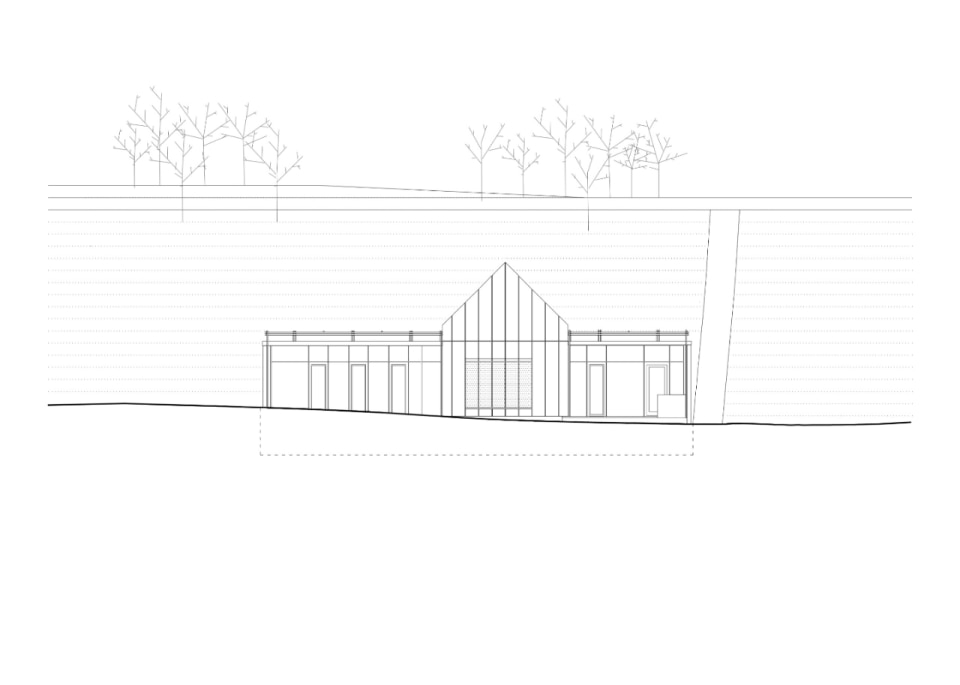

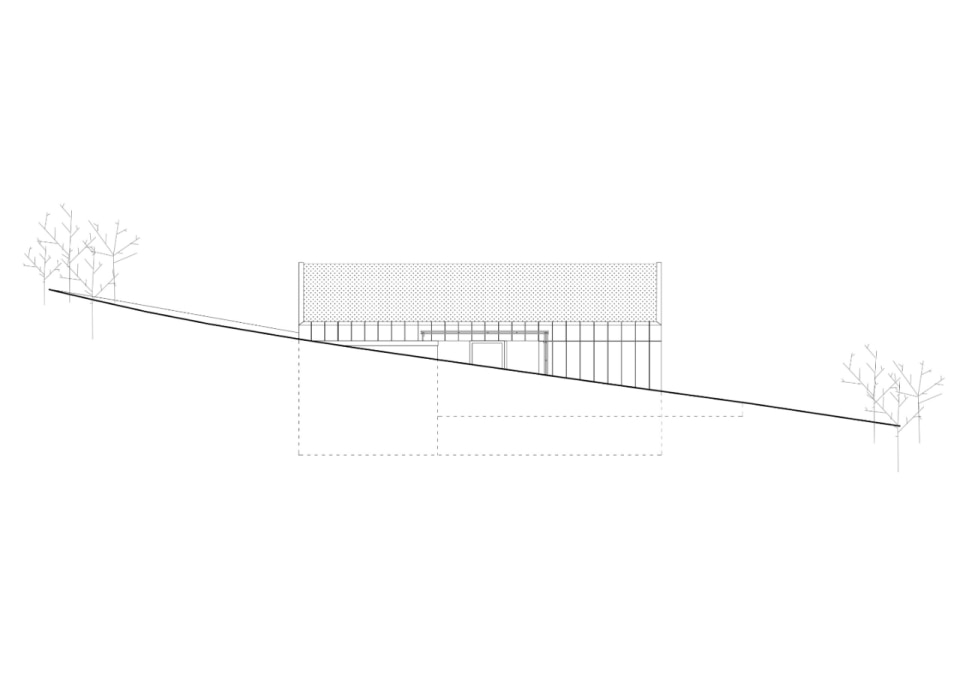

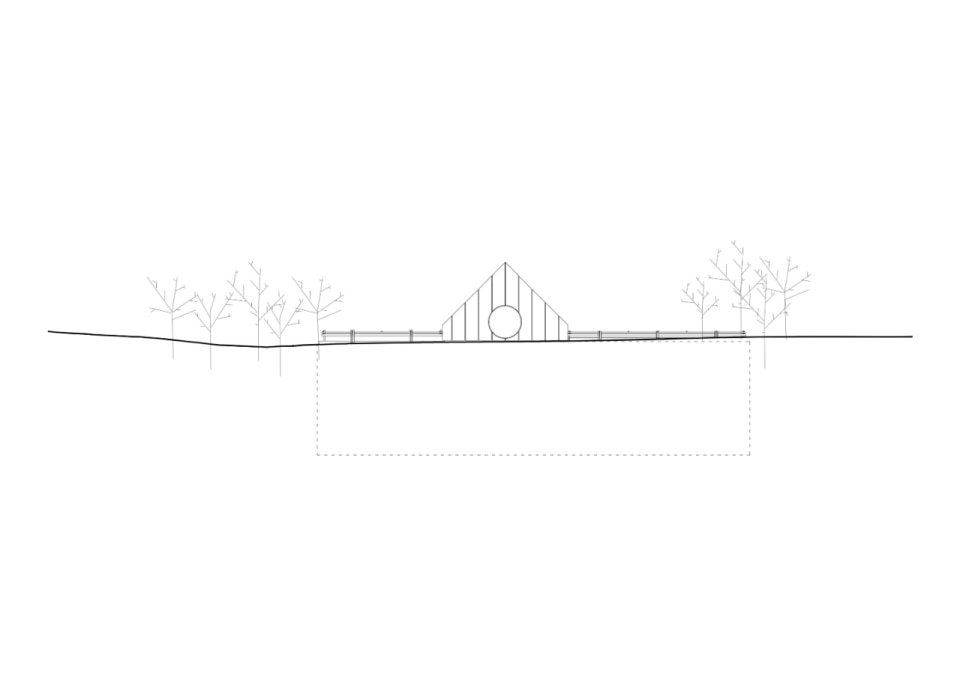

In a single project, born of the very contours of the site, the studio has not only combined a striking multiplicity of contemporary themes – apparently independent – but also reinterpreted motifs from architectural history through a distinctly current lens. Two orthogonal volumes define the house: one, containing the bedrooms, is an underground architecture of the kind that, since Wright, has lent modernism its organic dimension; the other, hosting the living areas, is a materialization of the archetypal hut. And yet it also functions like those telescope-like solids with which Herzog & de Meuron have marked recent decades, inhabited within by the luminous, symmetrical rigor of certain 1990s high-tech interiors and the monomaterial pale woods of today’s domestic language.

This house, behind the apparent simplicity of a lakeside dwelling, embodies a distillation of references to the history of modern architecture and the challenges of the contemporary.

Looking closer at the material choices, this eclecticism multiplies. Pale woods line the living room entirely and, on the inner façade of the “hut,” become a full-height library wall that saturates the surface and frames the landscape through a single, garden-level window. These raw woods, dialoguing with equally raw exposed concrete, are present throughout the house – in wardrobe fronts, bed structures, and doors – set against vintage details such as circular switches, and warmer textures like parquet floors and sand-toned terrazzo. In the kitchen, a different dialogue unfolds: the hi-tech suggestion of a fitted wall with metallic finishes and abstract pendant lights meets a masonry table, its pink terrazzo recalling the patterns and chromatics we might call “millennial”.

Very quickly, the house establishes a “landscape of surprise.” Its seemingly intimate interior in fact “escapes” in every direction: through the glazed walls of the bedrooms, the living room’s transparency onto a patio nestled in the hillside, and the visual continuity between levels and openings in the living-studio space. It is an effect reminiscent of the Raumplan in Adolf Loos’s houses – and Vienna, after all, is not far away.

Once outside, the palette shifts again: the night zone blends in with reflective glazing and green roofs dissolving into the slope, while the day zone asserts itself through metal – light pergolas and expansive corten surfaces.

The sense of disorientation is complete, even as the house attempts discretion within the landscape. The references it generates are so many that it becomes difficult to decide whether one is looking at underground architecture, a house in the woods, a camouflage house, or a house of mirrors. And at the upper edge, where the final slice of façade is cut in half by the meadow – like a metaphysical tympanum, the likes of Bomarzo or Scarzuola – the vision of architecture as an eclectic machine is brought to its fullest expression.