After exploring space in 2022, the International Exhibition of the Triennale returns to Earth to find it in a sorry state. “Inequalities” is the theme of the 24th edition, which marks a century of exhibitions. The first took place in 1923, and ten years later it moved into the building still known today as the “Triennale” — the Palazzo dell'Arte by Muzio, a stone's throw from Sforza Castle and on the western edge of Parco Sempione. Despite its age, the building is constantly evolving — see, for instance, the recent opening of Voce on the 'park floor'.

“Telling the story of inequality today means reflecting on what generates injustice for both humans and the planet. It means examining cities and their future, and considering architecture as a means of raising collective awareness,” writes Triennale president Stefano Boeri in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition.

Every city can serve as a good example for the others in the hope of achieving more sustainable development.

Nina Bassoli

Inequality should not be confused with diversity, which is a source of richness instead. However, the two concepts are linked: inequality can be seen as a distorted or negative form of diversity. This is one of the exhibition's key concepts, as it cannot address one without the other, though it tries to draw a line between them.

At the entrance to the Palazzo, a digital monolith by Pentagram — probably the world’s most famous design studio — introduces the theme of inequality through an effective and familiar medium: data. Curated by Giorgia Lupi, a designer known for her 'data humanism', the installation makes heavy use of numbers. Pentagram also designed the exhibition's entire visual identity, including 18 signs to guide visitors.

Such exhibitions are known for being dense with ideas and information, and this one is no exception. While you may feel that "you can't really see everything" or "it takes hours to visit", the layout of this 24th edition is actually quite clear, despite a few darker corners. And yes, there is a lot to see.

Also based on data is the large installation at the back of the main entrance hall, "Forms of Inequality", in which Federica Frangipane turns data into sculpture. It is located where the Triennale bar used to be (it has now moved downstairs to where Voce is).

The simplest way to navigate the exhibition is to note that the ground floor is dedicated to geopolitics and the upper floor to biopolitics. Returning to the ground floor, the main focus here is on cities — the environments in which most of the world’s population already lives, and will increasingly do so in the future. However, cities are also where inequalities are most visible. The curators repeatedly reference Chicago, where neighbouring districts — one wealthy and one poor — have a life expectancy difference of 30 years.

The “Cities” exhibition, curated by Nina Bassoli, forms the cornerstone of the 24th Triennale. It presents an 'atlas of places' comprising 43 cities, each of which “can serve as a good example for the others in the hope of achieving more sustainable development”. The exhibition begins with London’s Grenfell Tower, moves on to global cities and 'non-cities', as Bassoli calls them, and concludes with an in-depth exploration of Rome. Themes such as housing inequality, positive case studies and the coexistence of humans and animals are all highlighted.

In dialogue with the “Cities” show is the exhibit on Milan—its contradictions presented through a mix of data and creative interpretation. This same approach is reflected in the powerful (and already widely discussed online) installation on the grand staircase leading to the upper floor. Titled “471 Days”, it’s dedicated to those killed in Gaza from October until today, emphasizing one stark number: the death toll. You pass through this depiction of ongoing war to reach the upper floor, which shifts from geopolitics to biopolitics—as though walking through death is required to reach the realm of life.

The relationship between the two levels can be summarised in various ways: pars construens and pars destruens, hardware and software, macrocosm and microcosm, body and mind. The most evident is geo vs. bio.

While most people now understand geopolitics, biopolitics is less familiar. Coined by the French philosopher Michel Foucault, the term refers to how power operates over living populations, their bodies and their health. Foucault explored this concept through a genealogical lens, tracing the development of medical, social and political structures. His influence is especially evident in “We the Bacteria”, curated by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley — the theoretical core of this exhibition. The subtitle, “Notes for a Biotic Architecture”, hints at the show's fragmented nature and its connection to 20th-century architectural discourse.

The exhibition opens with an anatomical bust and a giant suspended ring representing the surface area of the human intestine. It then explores the Western obsession with hygiene, which is said to have made us more 'advanced', but which has also diminished our microbial diversity and made us more vulnerable. However, don't worry — architecture remains central, particularly in relation to “diseases of the built environment”. The underlying message is that we need to rethink design by viewing humans as mobile ecosystems.

The theme of biodiversity and self-care continues on the upper floor with “Eight Stations on Planet Earth” by Telmo Piovani (including a section on Milan) and “The Republic of Longevity” by Palmarini and Sammicheli. There is naturally a lot more, including national pavilions (notably those of Ukraine, Puerto Rico and Lebanon, though the pavilions of Togo, Poland and the Roma and Sinti are also worth a visit), a large space dedicated to guest editor Norman Foster for Domus 2024, a DS+R installation, the Radio Ballads project by Serpentine, an AI exhibit by the Polytechnic and Theaster Gates' incredible ceramic collection.

There's plenty to see, but it's not overwhelming, and it's well organised. While the quality varies and there are occasional missteps, the curatorship is evident. The theoretical framework is strong, delivering a punch on the ground floor and offering a shift in perspective upstairs. Unlike the last Venice Biennale, Triennale's exhibitions rarely make you feel lost in a chaotic maze.

1. Puerto Rico Pavilion

The elevated toilet, hidden behind colourful ribbons and set up by Puerto Rico on the ground floor of the Triennale, is a powerful example of how an exhibition can effectively convey a relevant contemporary story. “Once Upon Three Feminicides” commemorates Neulisa Alexa Luciano, a Black transgender homeless woman who was murdered in her tent on 24 February 2020. Just hours earlier, Alexa had been photographed in a public restroom, with the image being posted on Facebook by a user who accused her of spying on children’s genitals. Curator Regner Ramos represents the restroom, the tent and Facebook as the physical and digital spaces where gender-based violence occurred and was amplified.

2. Lebanon Pavilion

Right next to Puerto Rico’s pavilion is Lebanon’s, titled “and from my heart I blow kisses to the sea and the houses”, this exhibition centres on a house from the 1920s located along Beirut’s waterfront, which has silently witnessed the multiple acts of violence that have hit the city over time. These include not only the devastating 2020 port explosion, which left deep wounds in the urban fabric, but also the long-standing absence of urban planning, which has led to the systematic dismantling of much of Beirut’s architectural heritage. As a form of protest and remembrance, the owner has chosen not to rebuild the house, instead inviting artists to give it a voice.

3. Ukraine Pavilion

Ukraine highlights internal inequalities within the country—an unavoidable reflection on its three-year-long war. There is a disparity between those living in the eastern and western regions—those farther from the Russian border and less exposed to attacks. Even starker is the gap between those who have fought and those who haven’t, between war amputees and citizens expected to show respect, not pity. “Ukraine: Inhale/Exhale!” includes high-impact visual works: a large wall with scarred hands at its center, a sculpture symbolizing inner strength amid physical destruction, a VR installation on the destruction of the Kakhovka dam, and more. At the entrance, curator Khrystyna Berehovska notes: “Our art speaks of paradoxes: strength in fragility, resistance in survival, and the dream of peace amid chaos.”

4. The presence of Milan

The host city is a prominent feature of this 24th International Exhibition, appearing multiple times from different perspectives. On the ground floor, Milan is featured in the “Cities” exhibition, curated by Nina Bassoli. This exhibition showcases a metropolitan area model titled “The Space of Inequalities”, created by the Politecnico di Milano. Paradoxes are further explored in 'Milan: Paradoxes and Opportunities', which is held at Cuore, the Triennale's research and archive centre. Curated by Seble Woldeghiorghis, Damiano Gullì and Jermay Michael Gabriel, director of Black History Month Milano, the exhibition explores the contradictions that characterise the city today. Starting with data collected by Bocconi University, six major paradoxes were identified and assigned to artists to interpret and present in artistic form. These range from housing and income vs. rent to green spaces and accessibility.

On the upper floor, dedicated to biopolitics, Milan is part of 'A Journey into Biodiversity: Eight Stations on Planet Earth”, curated by Telmo Piovani. Among the sentinels collecting scientific data and organic materials is a plant that grows uniquely on the walls of the Castello Sforzesco.

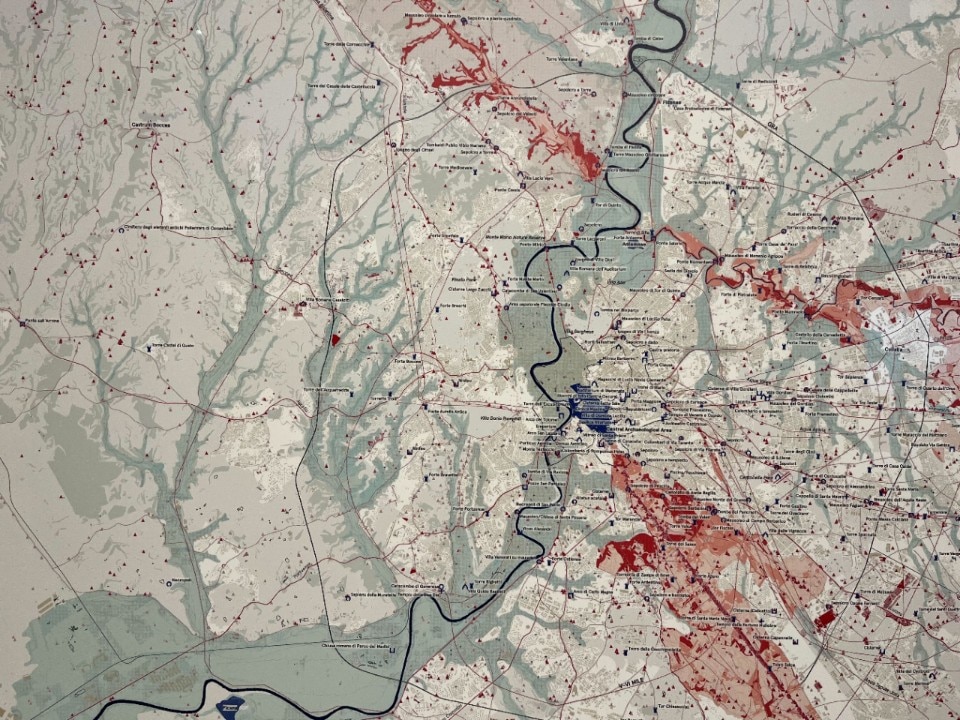

5. Archaeological Rome

Another urban map offering a vision of possible future transformations is that of Rome, which is also featured in the “Cities” section. “Subversive archaeology” is the term used to describe the year-and-a-half-long study by Laboratorio Roma050 which revealed an astonishing number of archaeological sites across the capital's metropolitan area. “How will life change in this unique metropolis where archaeology and history intertwine with biodiversity and geopolitics?” the curators ask. They offer a reflection on archaeology as a dynamic, living and generative resource, capable of redistributing not only material goods, but also the city's symbolic and cultural capital.

6. Alejandro Aravena's open source projects

A section of “Cities” is dedicated to urban regeneration as a project of care, listening and layering. This section includes experimental studies by international universities, as well as long-standing examples such as the Plug-In Houses by People’s Architecture Office in Shenzhen. Notably, it features open-source housing projects by Alejandro Aravena and his studio, Elemental. They make their housing prototype blueprints publicly available. Similar to pro bono projects by architects such as Shigeru Ban, which often respond to emergencies like the 1995 Kobe earthquake or the current war in Ukraine, Elemental’s open-source plans emphasise the urgent need for collective action in today's world.

7. The Intestinal Theatre and the hygiene product library

On the upper floor is the major exhibition “We the Bacteria: Notes for a Biotic Architecture”, curated by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, begins with two striking, interconnected installations. A wall of personal hygiene products represents our constant effort to eliminate dirt and microbes. Meanwhile, an expanded intestine hanging from the ceiling reminds us that bacteria are already inside us. The exhibition suggests that the human body should be understood as a mobile ecosystem within a microbial world.

8. The benefactors of the Ca' Granda

“Portraits of Inequalities. Class Painting” is both a collection of portraits and a tribute to the social pact—especially relevant in a time when the wealthiest 1% appears increasingly detached from the fate of the poor. These 17th- to 19th-century paintings depict 30 male and female benefactors of Ca’ Granda, the old hospital of Milan, now the Policlinico. In return for a generous donation, patrons would receive their portrait. Upon entry, one immediately sees Hospital Life Scene, a painting depicting a typical day in what is now the courtyard of the University of Milan, with figures from all social classes.

9. Norman Foster's mini-houses

The Norman Foster Foundation's mini-house prototype was first presented at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. However, the research behind the project has continued. At this Triennale, the exhibition “Toward a Fairer Future” presents initiatives for the transformation of an informal settlement in India, the regeneration of a war-torn Ukrainian city, and sustainable yet high-quality housing solutions. Inside the exhibition, you’ll find a full-scale section model, and outside the Palazzo dell’Arte, there is a complete prototype.

10. Shapes of Inequality

Imagine turning a graph on global inequality into a three-dimensional sculpture.“Shapes of Inequalities”, curated by Federica Frangipane and located at the far end of the ground floor's central hall, does just that. Rather than flat visuals, its themes are 3D (and purple) representations of various forms of inequality that have been analysed, materialised and made visible.