Architectural historian and theorist Beatriz Colomina, full professor at Princeton University, has spent the last four decades deconstructing the contradictions behind established assumptions in our experience of built spaces. Such as the “modern” houses she analyzed in Sexuality and Space (1991): true devices of oppression and segregation, for women as for any living form deviating from the norm.

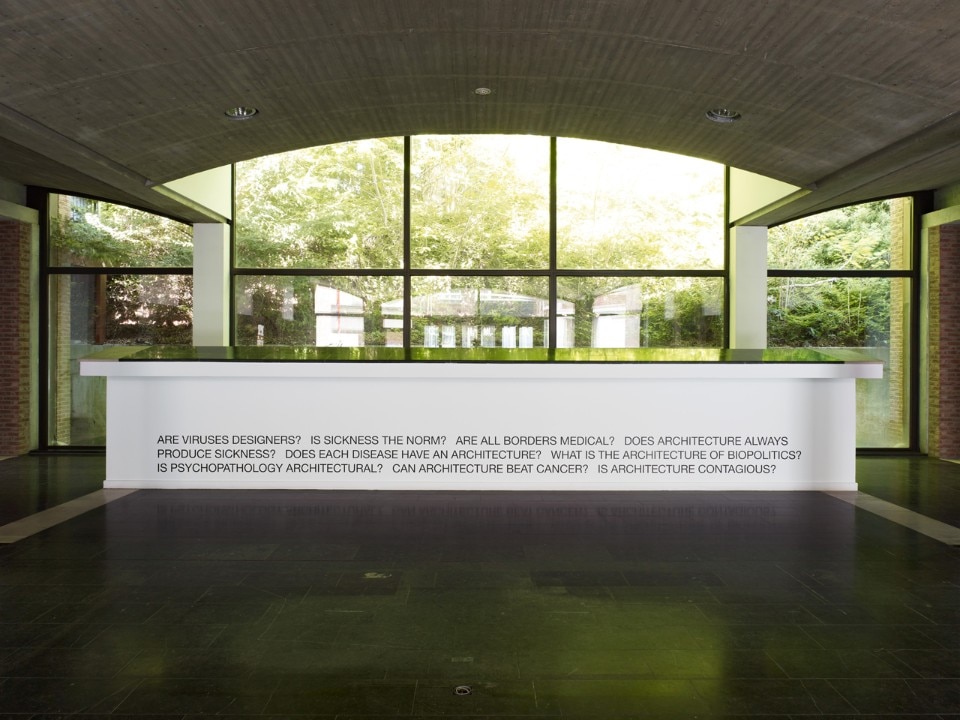

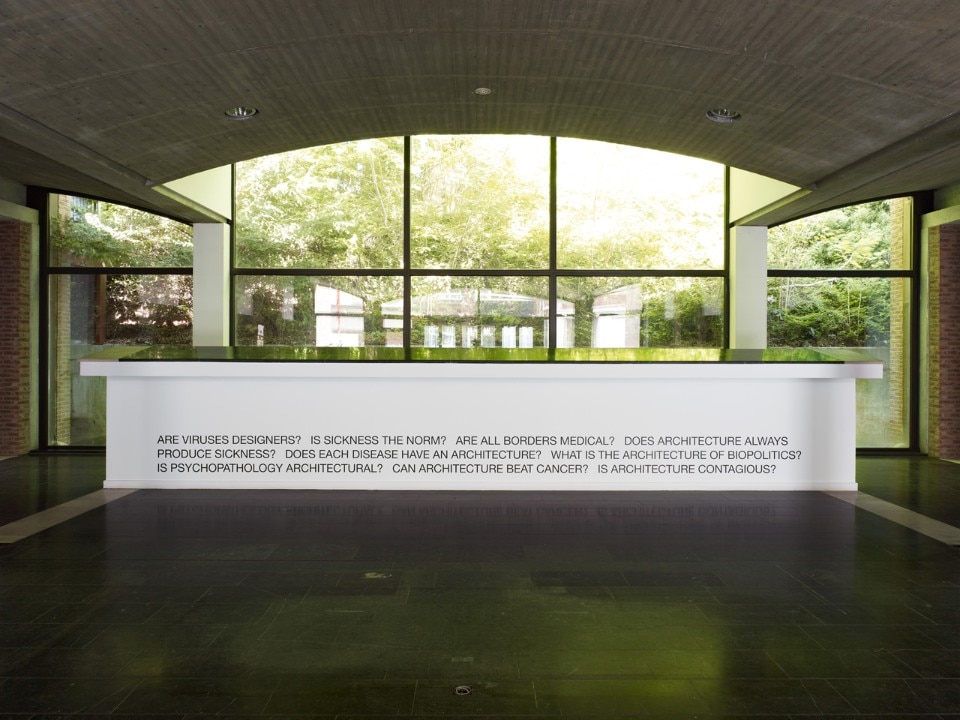

In recent years, she tells Domus, the relationship between architecture and illness has been the subject of her and her students' research. A pre-pandemic interest – she declares herself deeply struck by the disturbing timing of subsequent events – which in any case nobody wanted to dissipate during the lockdown period: a series of related essays on the e-flux platform has then been started, and now the exhibition Sick Architecture is open at the CIVA in Brussels, with a set design co-developed with Office KGDVS, combining the research works with other historical examples and contemporary art works, a tool for investigating a relationship of mutual determination which is still ambiguous.

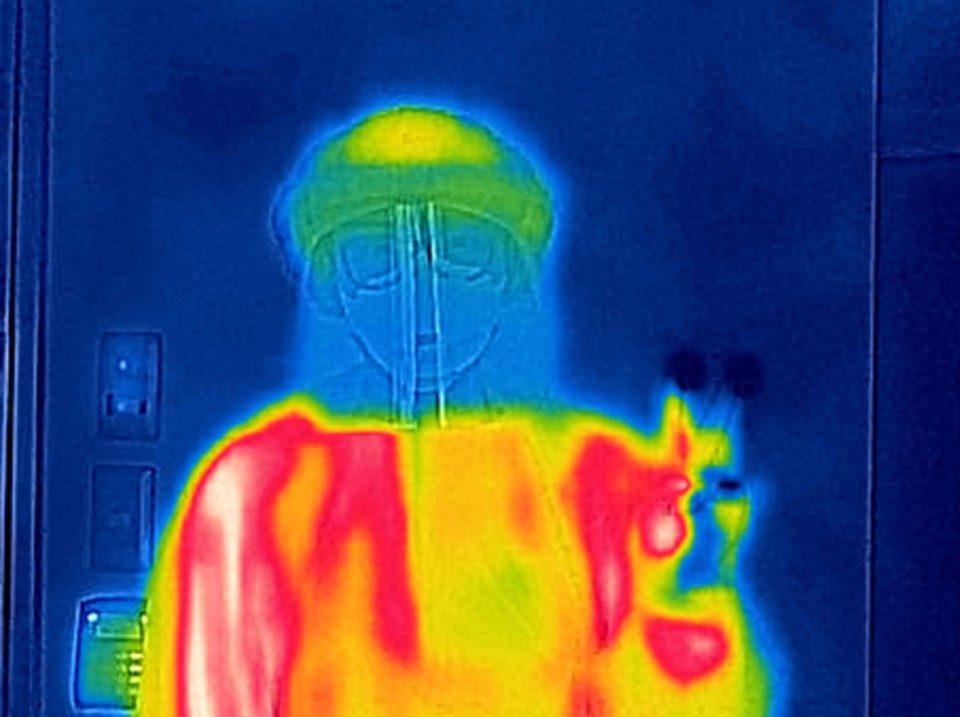

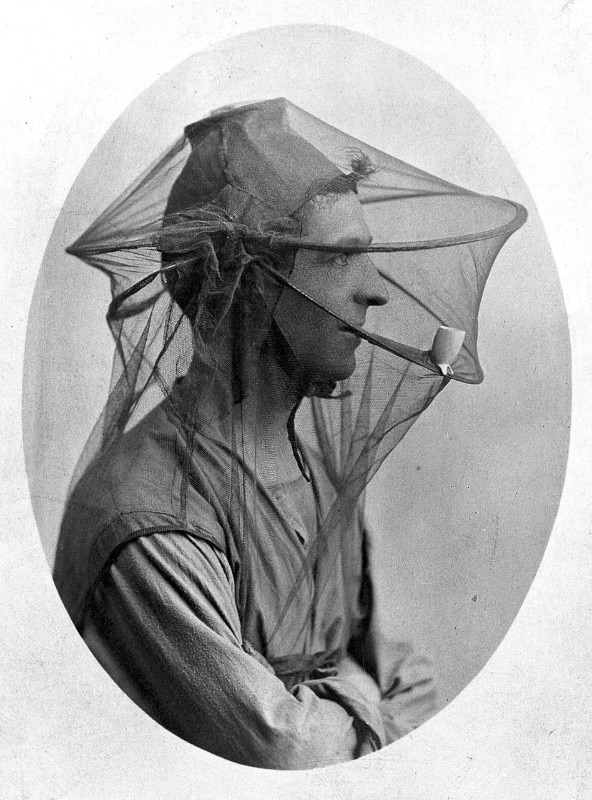

“This relationship between architecture and sickness” says Colomina “goes back historically a long time. The Greeks thought that the ideal city was a healthy city, later Vitruvius wrote that architects should study medicine, because health is their most important objective. At the center of all architectural treatises is the idea of a healthy body. Whether it's Leonardo’s man or the man of Le Corbusier, the Modulor, it's always a man, a white man, a healthy, athletic and exercised body”. Colomina stops, to stress that the idea is to say: no. “The center of architecture is a very fragile body that actually has to be kept at 36 degrees, and in certain conditions. Architecture is more like a cocoon that protects this body, a kind of orthopedic protection from the illness”.

“We are used to thinking of sickness as an exception”, she says. But sickness is not an exception: “we are sick all the time, we are made of millions of bacteria in some sort of balance. If we are lucky for a very short time we have that healthy athletic body; but when you are a baby, or when you are old, or sick, when you have any kind of disability, you are fragile”. The consequence is simple: the universal man that architecture has to serve is a fiction that doesn't actually exist. A big individual resembling nobody.

“So little by little, you see how the Neufert – the most popular architectural design manual and reference book, first published in 1936 – and all similar manuals through the years gradually started introducing a woman, then a child, then eventually a person on a wheelchair”. Finnish architect Aino Aalto and her husband Alvar are identified by Colomina as an interesting example of a radical repositioning on sickness. “When they were designing the Paimio sanatorium, apparently Alvar had been very sick, and having to stay in bed for such a long time, he realized a problem: architecture is always conceived for the man in the vertical position, but a patient lives constantly horizontal. Architecture’s not always designed for the person in the weakest position”. So, Colomina explains, if we design for the person in the weakest position, “then everybody else would be taken care of”.

The exhibition is conceived as a big collector and generator of questions, an investigation tool questioning the conceptual boundary of “normal” when it is applied to the sick vs healthy opposition in architecture.

The operation is a lot about shifting the perspective in which we are used to frame such (apparently oppositional) relationship.

“Is sickness the norm?” for example, means sickness is not an exception, but it's actually normal, and maybe what is pathological is actually architecture. “The problem with architecture” says Colomina “is that we both create the conditions for disease , then try to ameliorate it, claiming that our buildings are very healthy and protective for bodies.

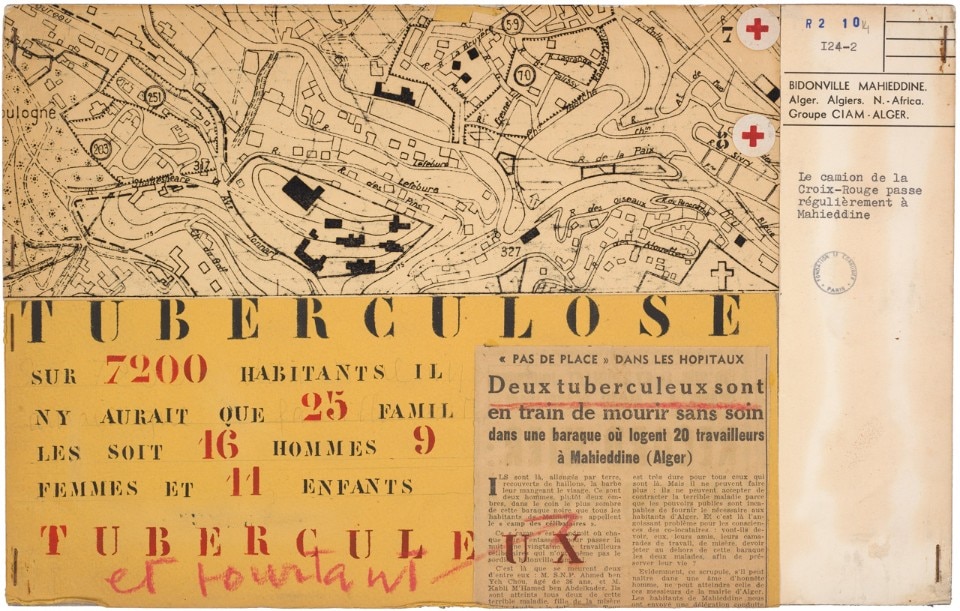

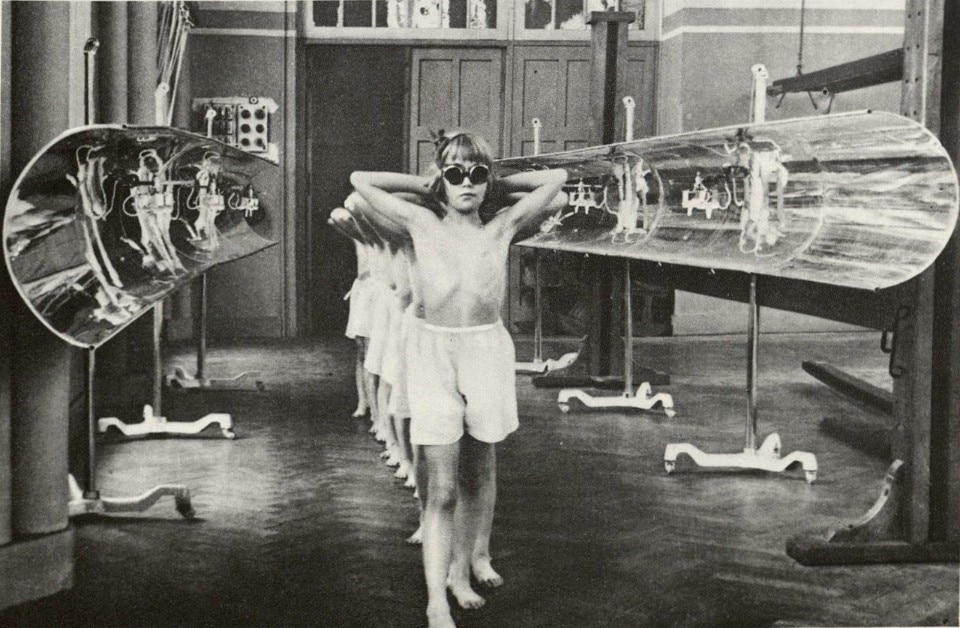

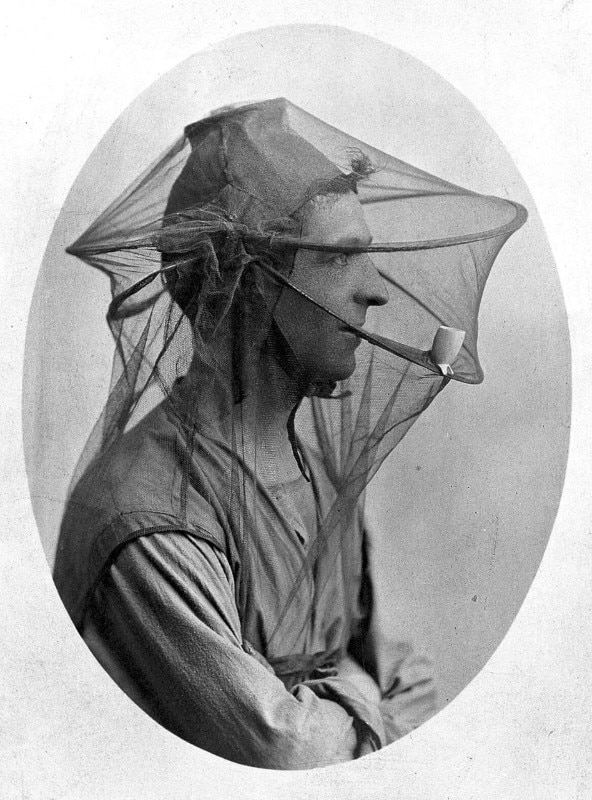

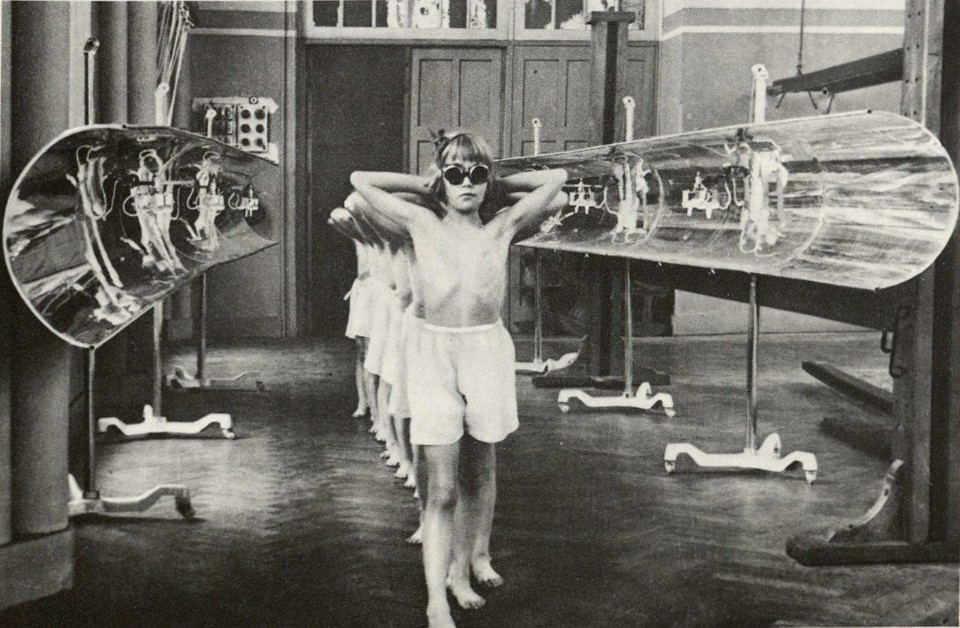

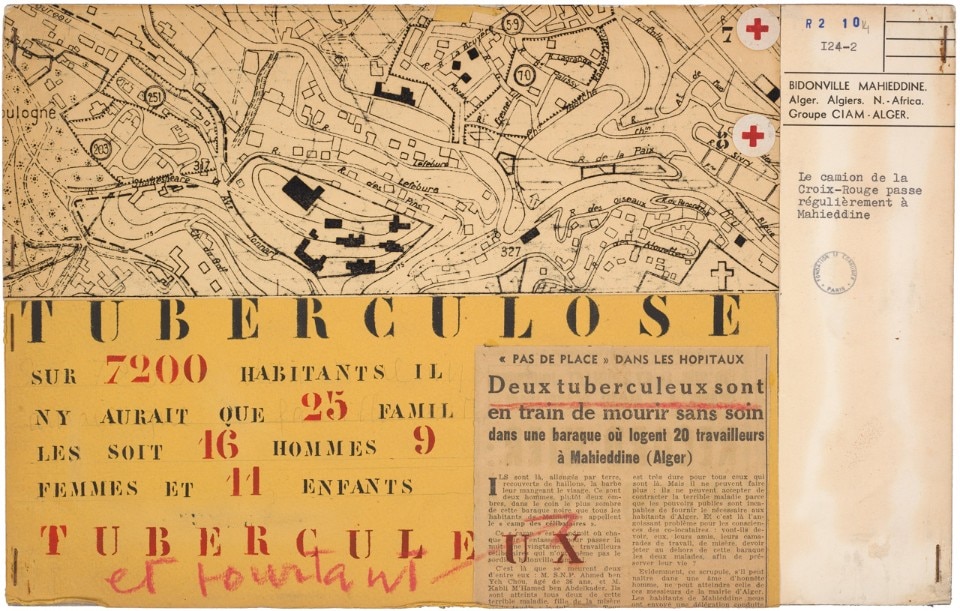

Doctors already in the 19th century said that man, in going indoors (already in the Neolithic), had constructed the conditions for diseases, such as tuberculosis.Then in the 50s, of course, there was a lot of toxicity created by the new materials, then the sick building syndrome came in the 70s, with the same buildings that we thought were so healthy with so much glass, in the strain to fight tuberculosis actually creating the condition for a lot of the skin cancers that are now part of our lives. So there is no disease without architecture and no architecture without disease”.

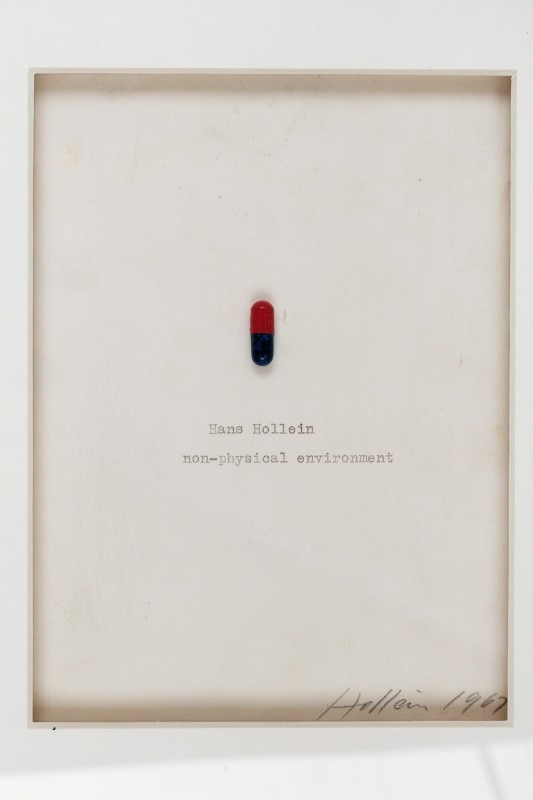

The question then extends to the definition of “normal” as a boundary made tangible through architecture, separating and segregating, cleaning and clearing the abnormal as it happened with the razing of the house of transgender activist Sylvia Rivera in New York. Such interpretation undoubtedly covers a crucial part of reality, but it might nonetheless result in being reductive, Colomina remarks, as in many cases the architectural, space-based interpretation of a health-based norm has also been “a tool for emancipation”. This has been the case of the Salpetrière hospital “where women diagnosed with mental illnesses, in 19th century Paris, would give public performances of their symptoms in front of large audiences, actually turning the hospital facility into an interface, an actual theatrical spaces they could take control of”; of the joint protest of Berkeley Vietnam veterans and architecture students leading to a transformation of urban landscape and the passing of American Disabilities Act; of the both metaphorical and material exploration of “an access to a new understanding of space as the idea of a pill for all kinds of questions” Colomina adds, “as Hans Hollein did when playing with pills as forms of architecture”, which are also shown in the exhibition poster, claiming that all is architecture.

In this perspective, the exhibition confirms its nature: an investigation tool, but most of all an archive tool, “an archive that travels and grows” Colomina says”and absorbs in a way the visitor’s reaction, like my former exhibition Radical Pedagogies was, in which people would stay in the Venice Arsenale taking notes sometimes from nine to five, so that chairs had to be finally put in the room”.