Marble matters– exploring Carrara’s legacy

Sixteen young international architects took part in two intensive training days in Carrara, organized by FUM Academy and YACademy, featuring visits to the marble quarries and a design workshop focused on the use of the material.

- Sponsored content

In this interview, Ellen van Loon, the OMA partner in charge of the project, explains how durability and flexibility of usage are inevitable characteristics of any truly sustainable building. She talks to us about the relationship with Danish Modernism and Dutch Structuralism, as well as the critique of the local tradition of urban planning embodied in Blox.

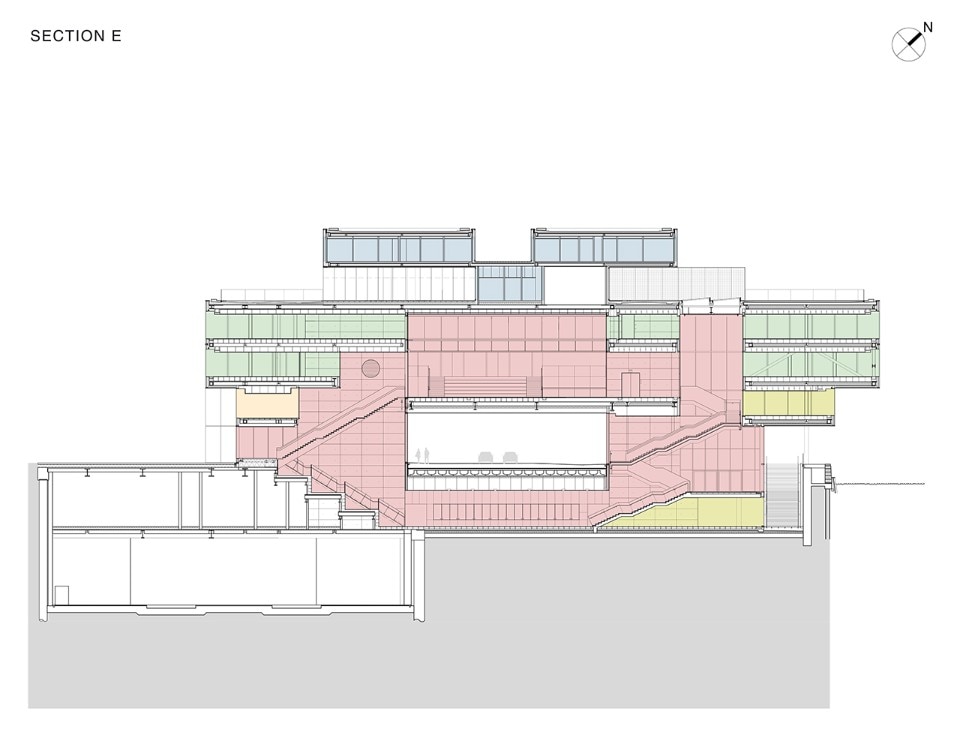

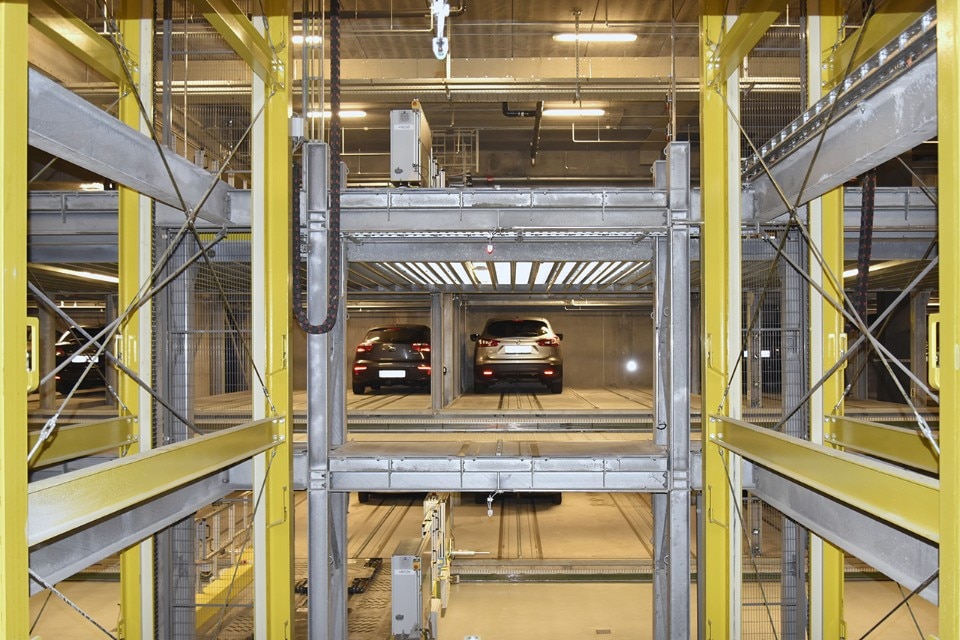

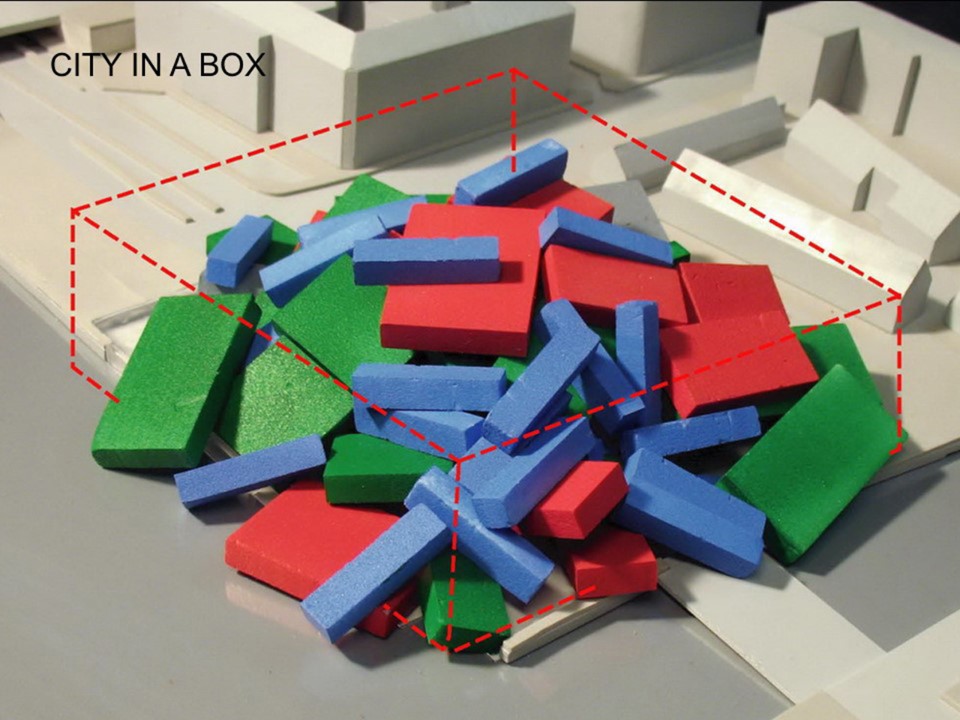

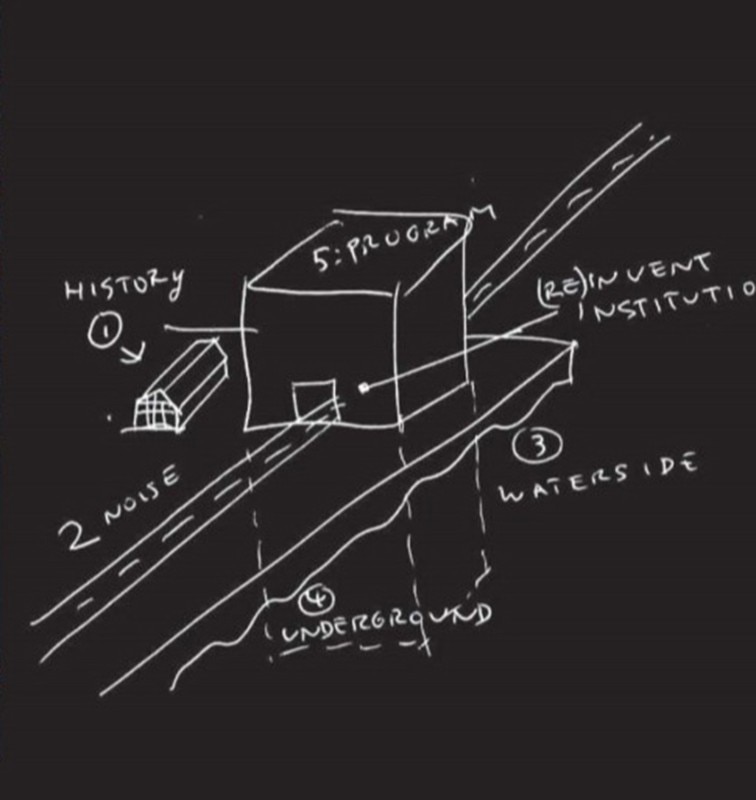

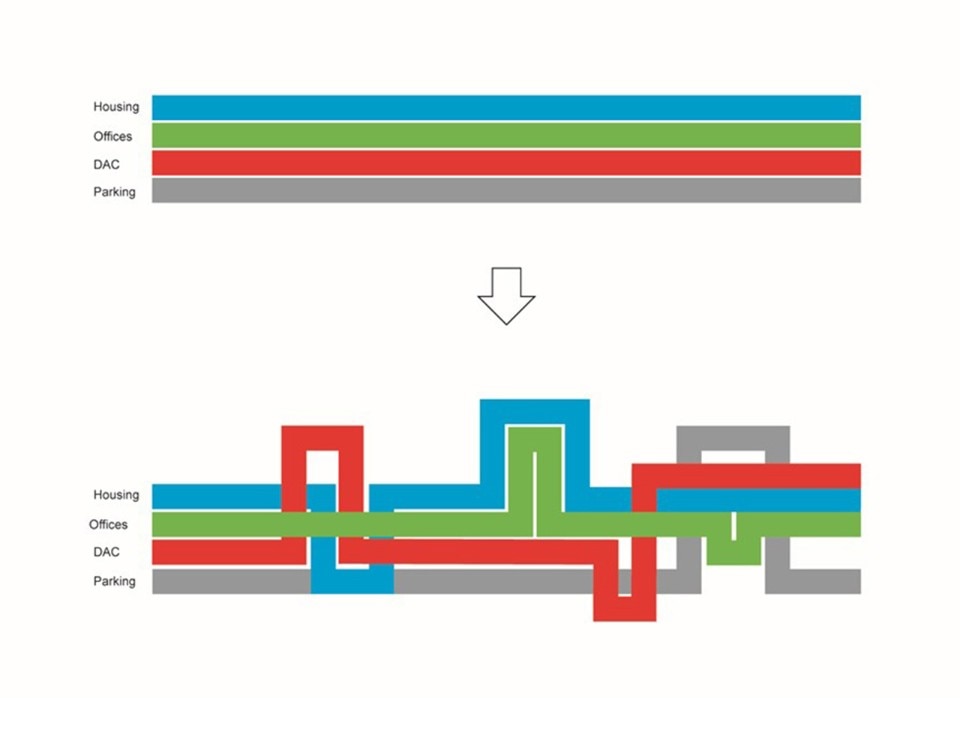

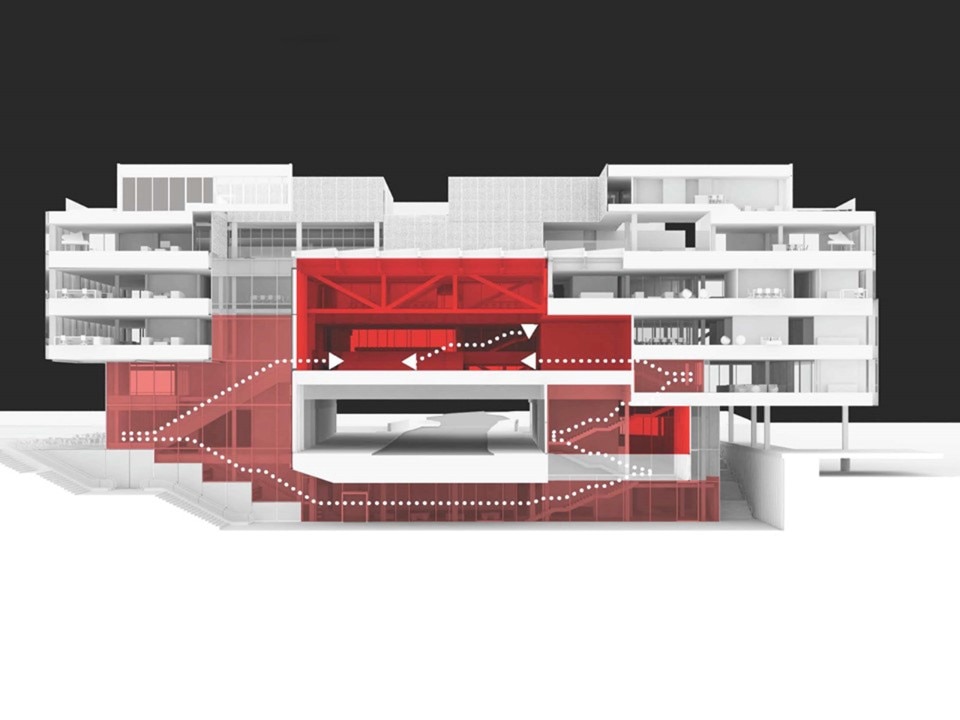

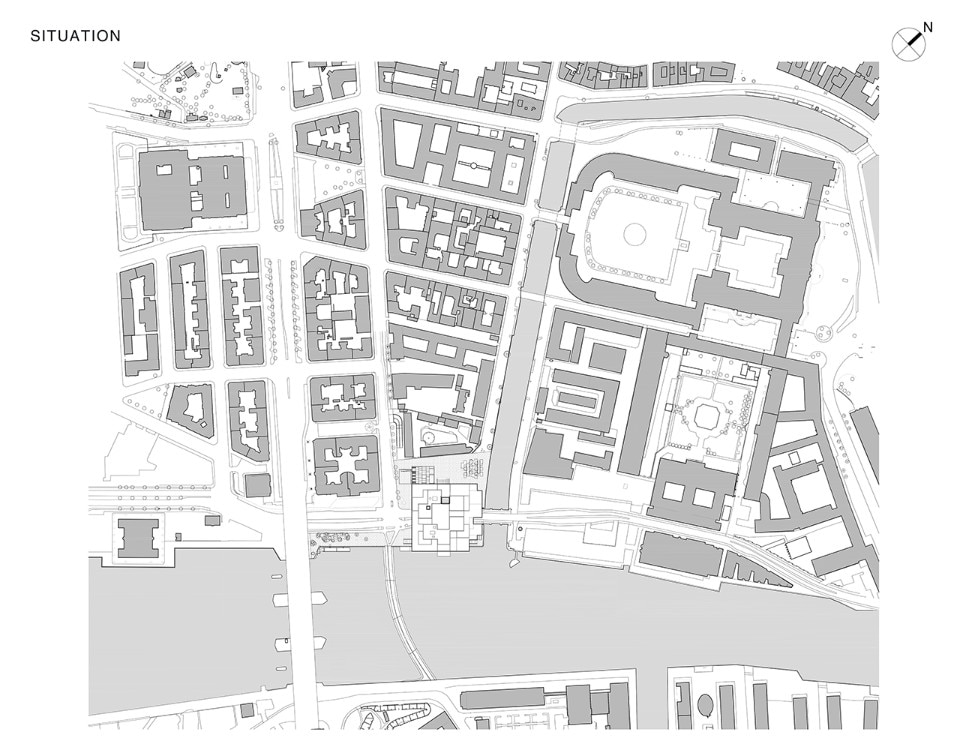

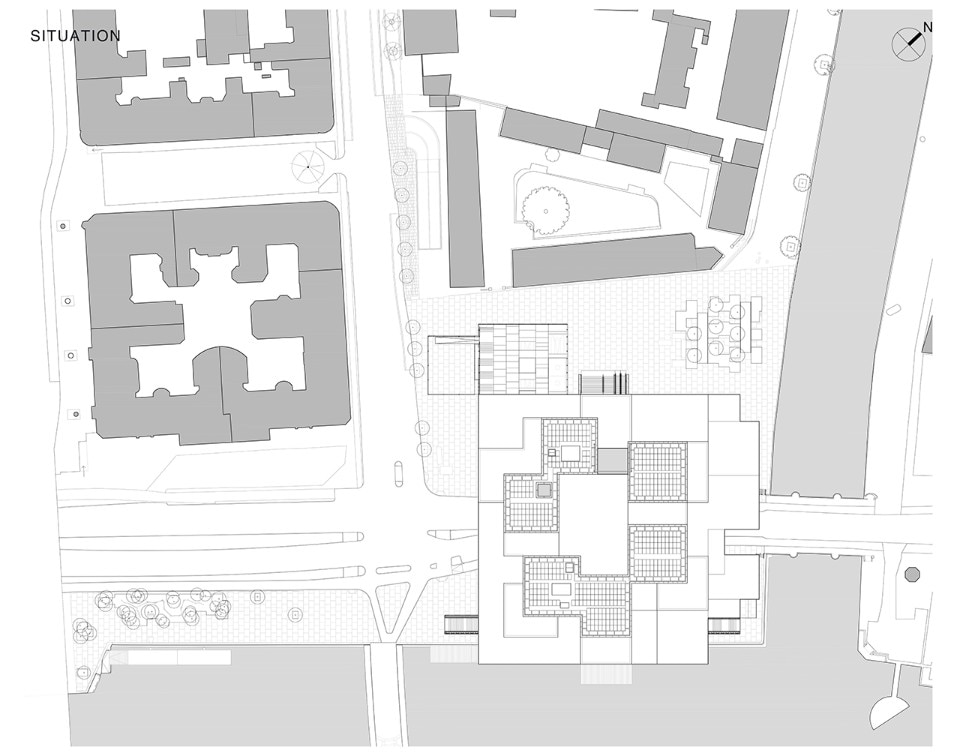

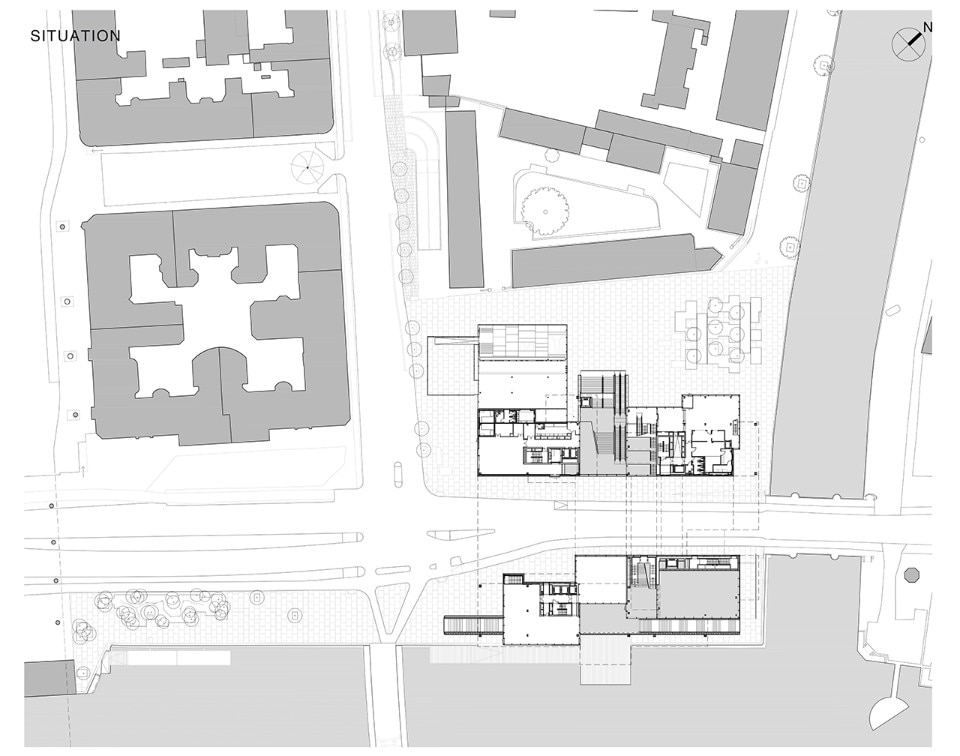

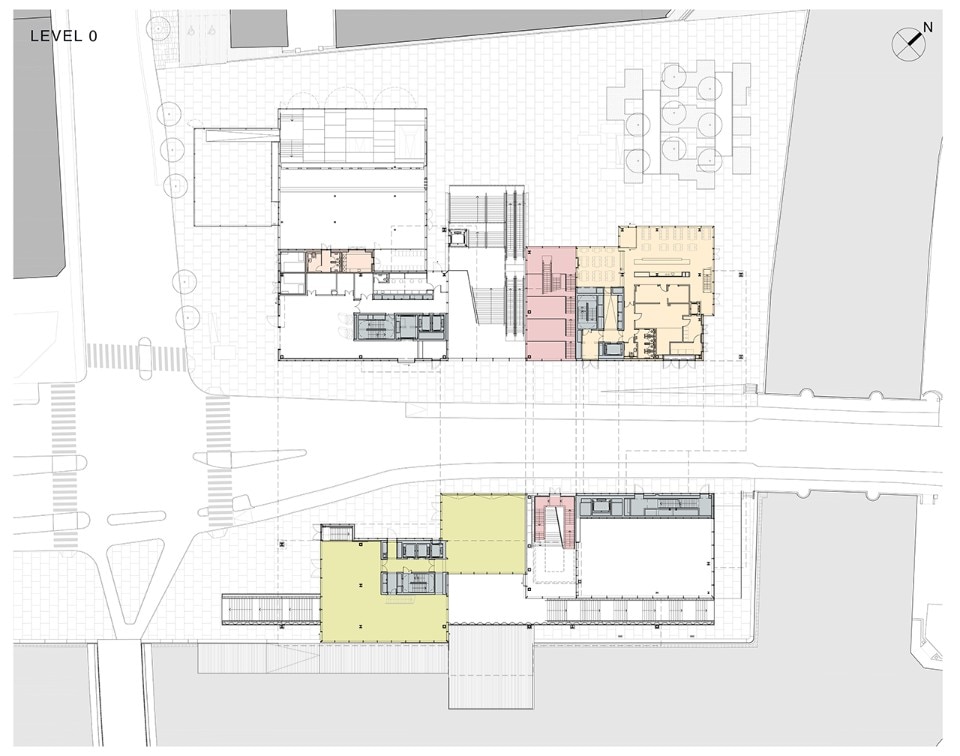

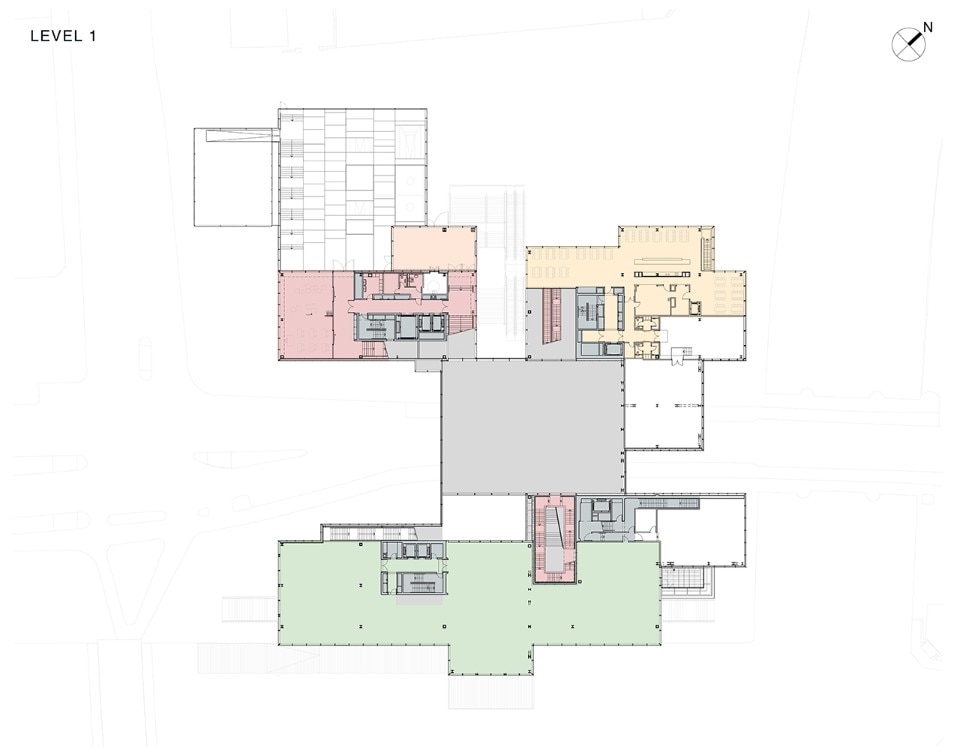

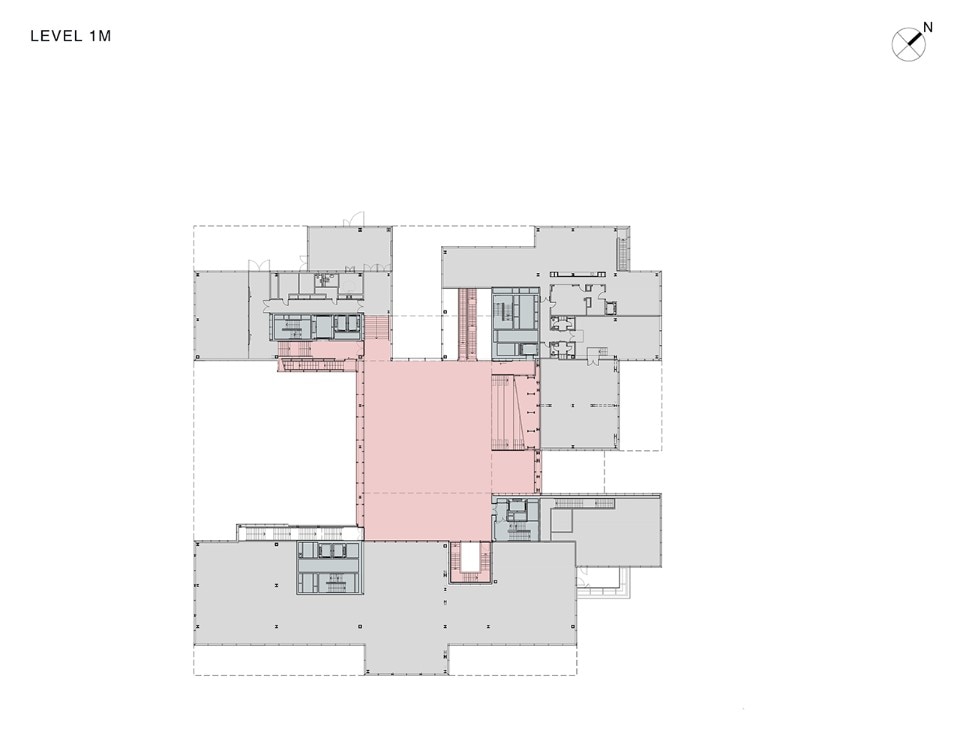

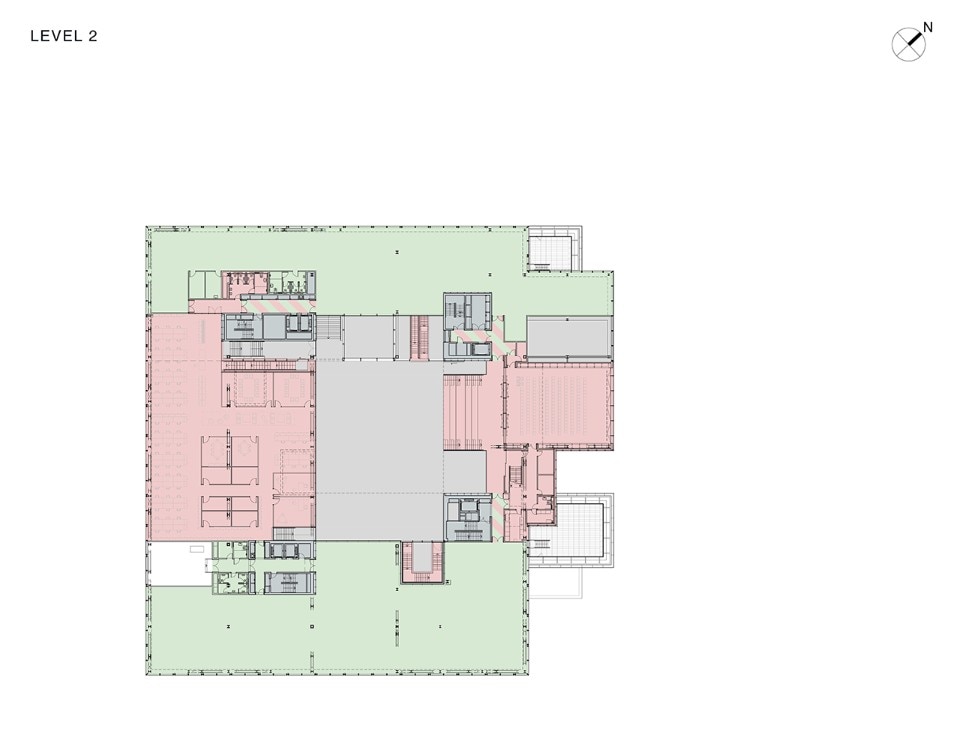

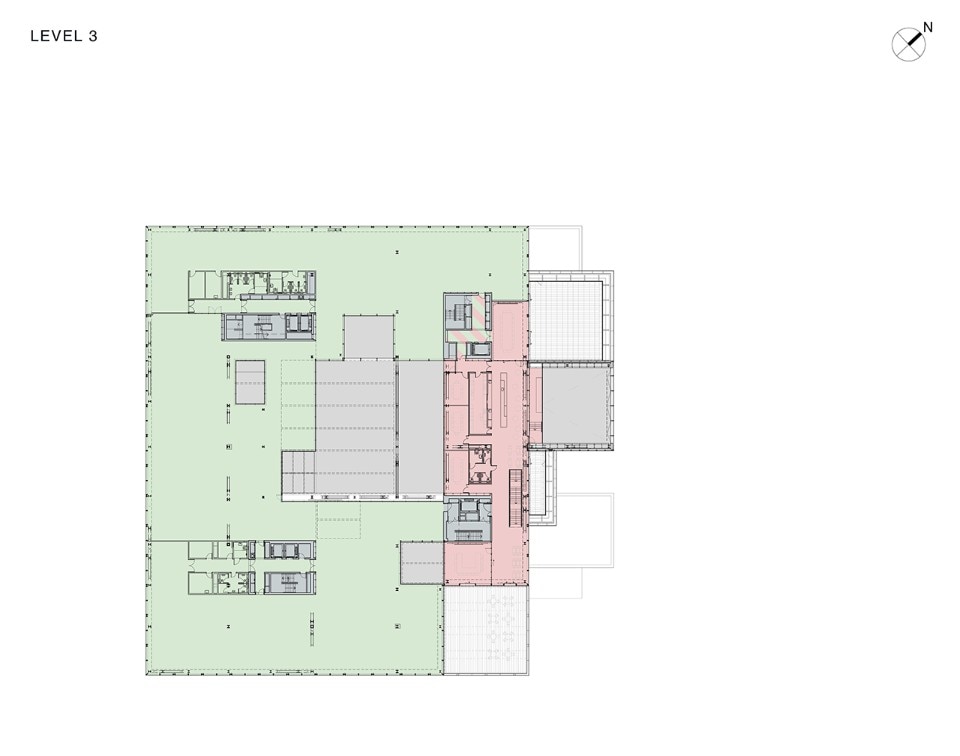

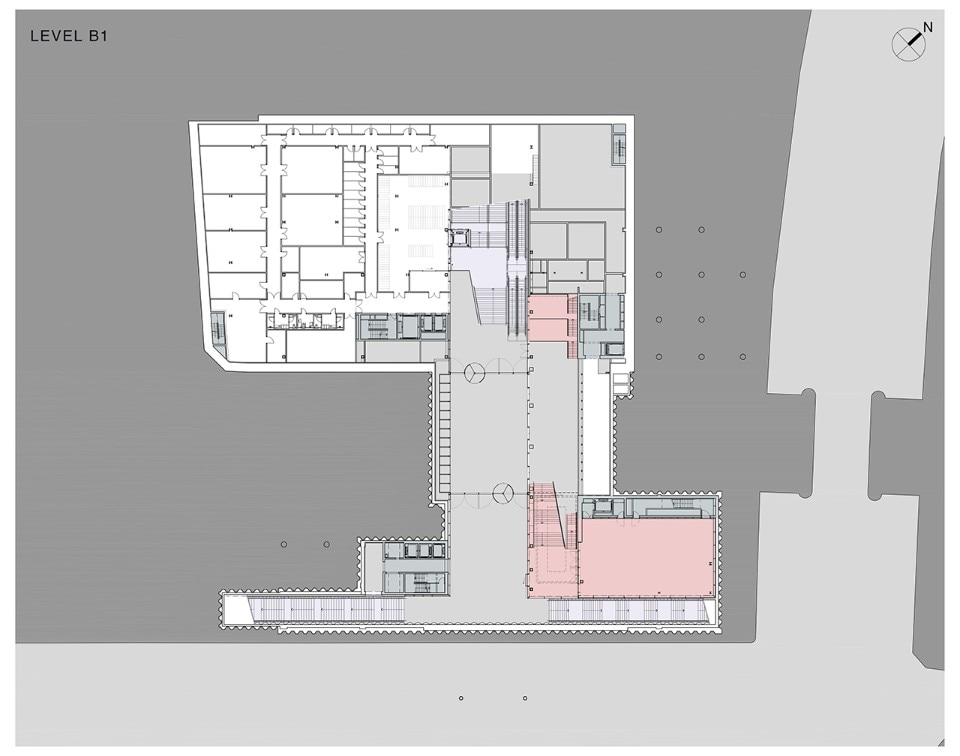

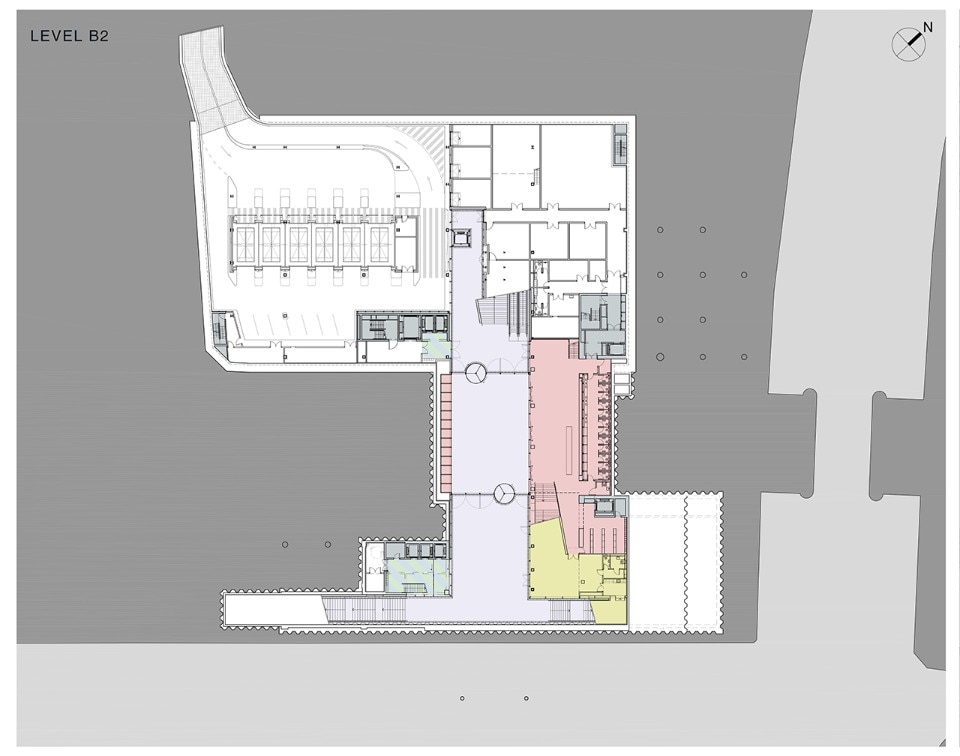

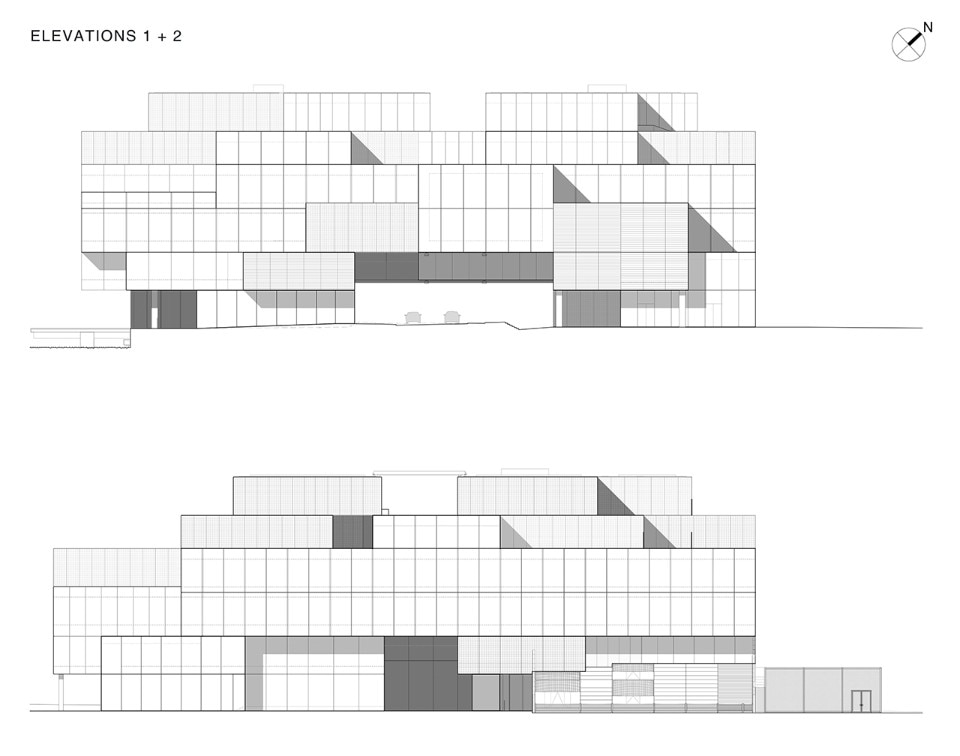

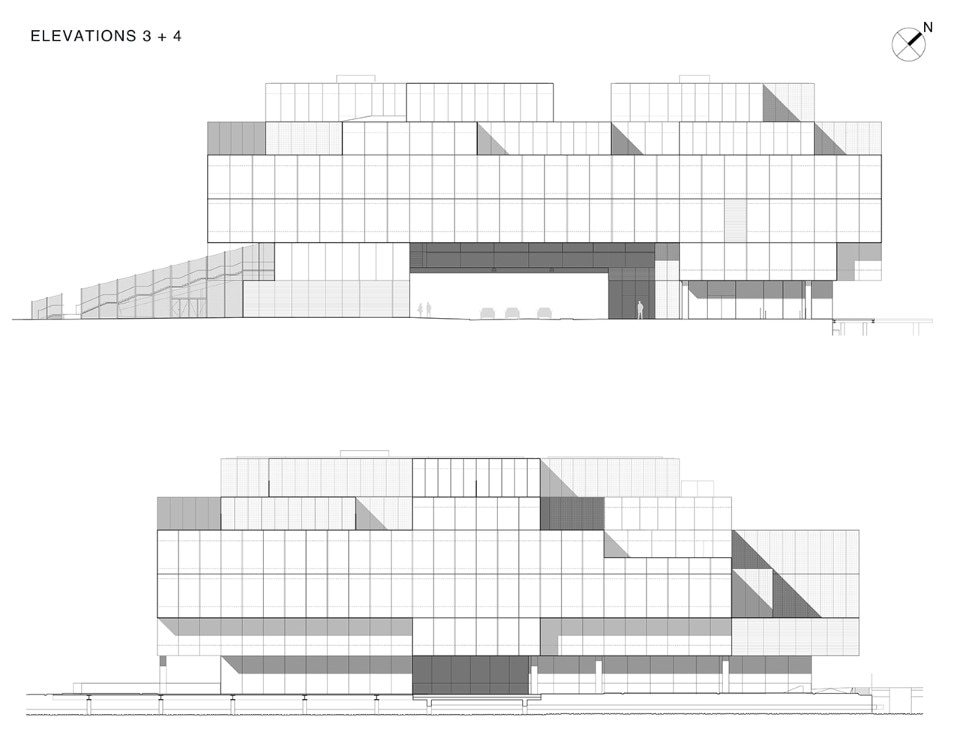

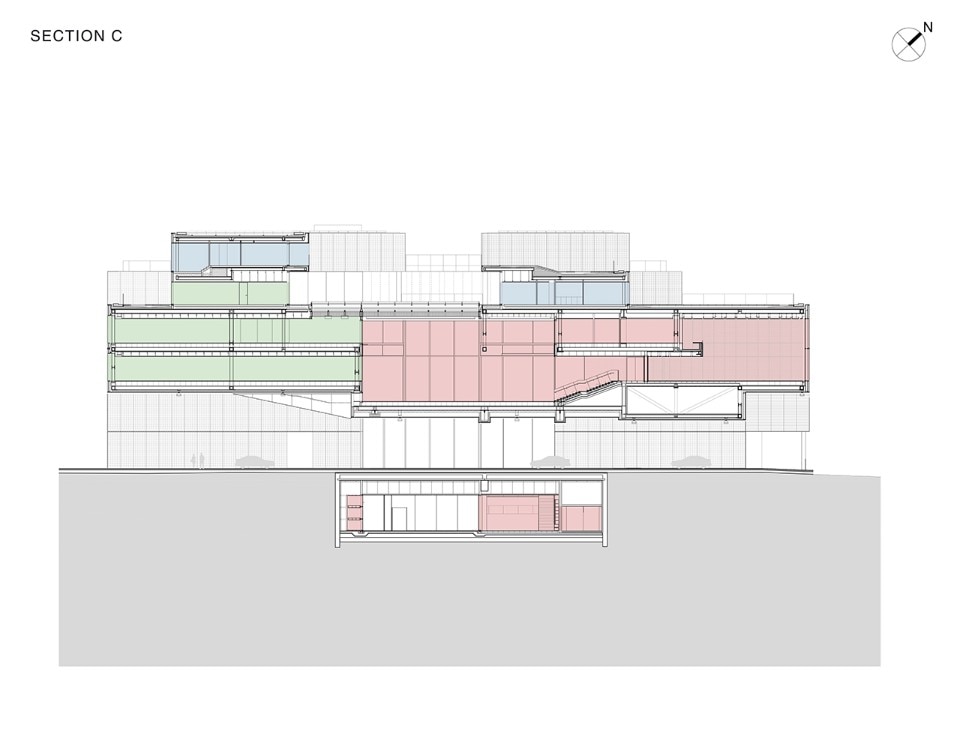

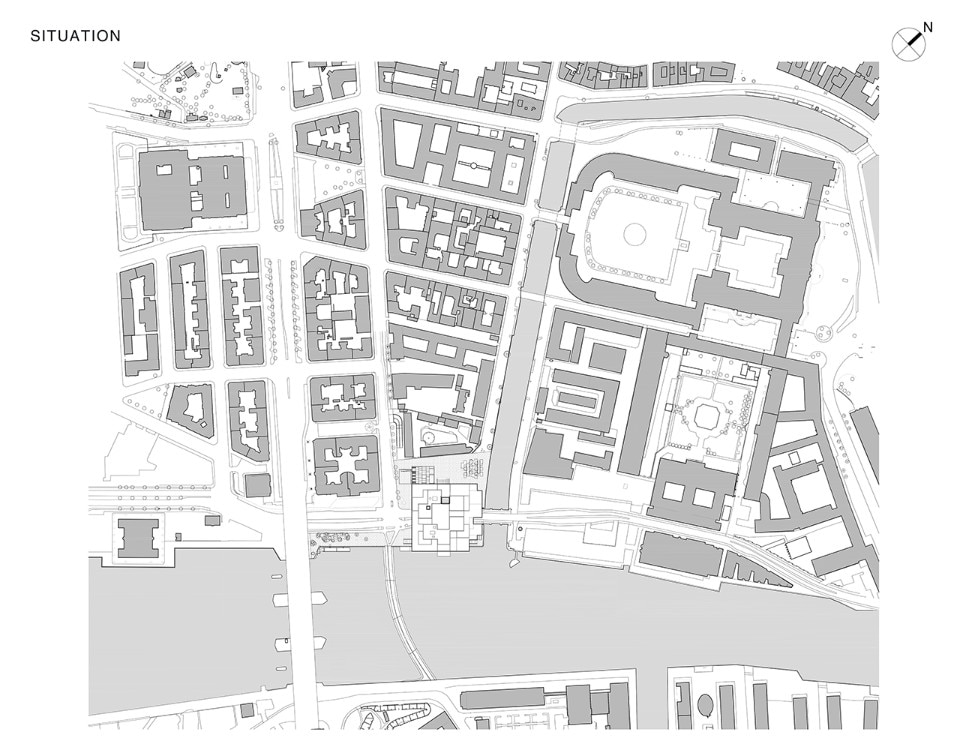

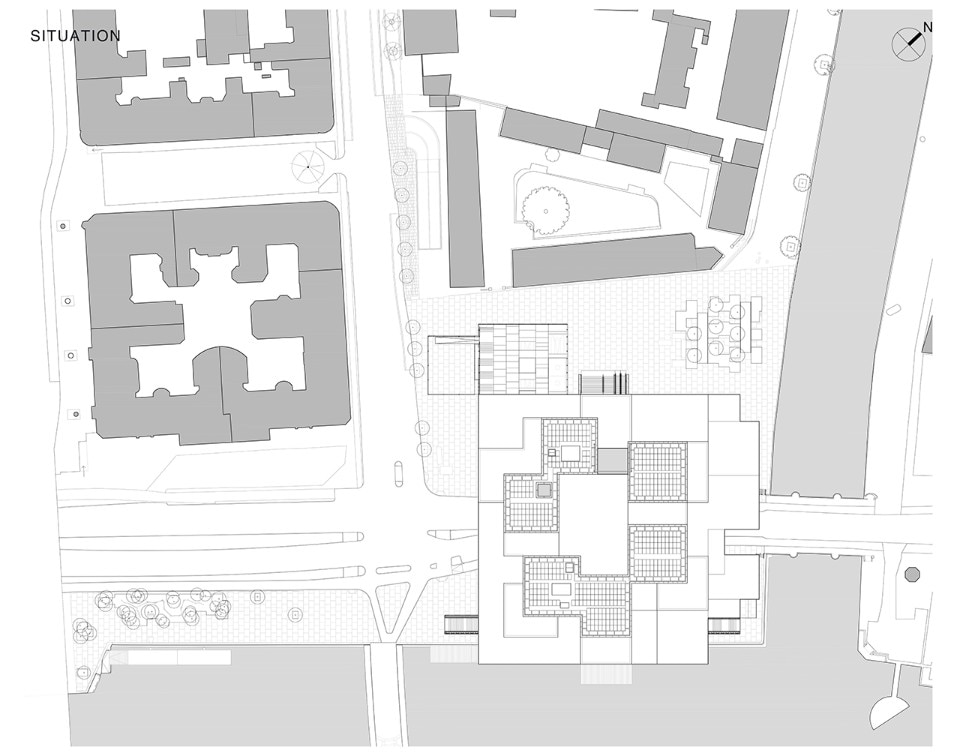

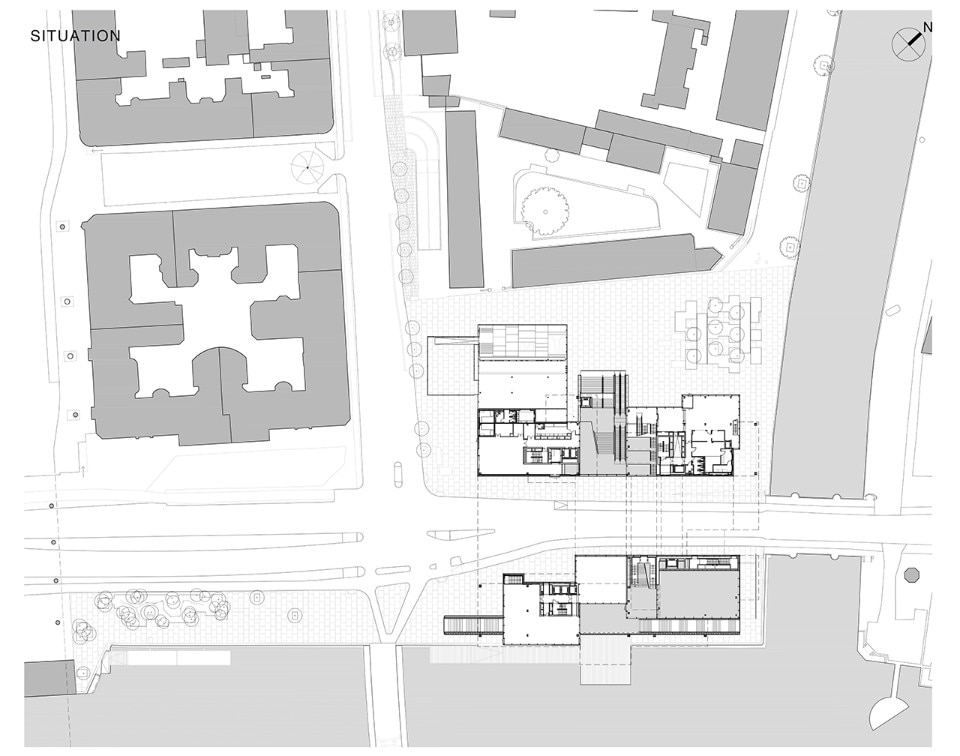

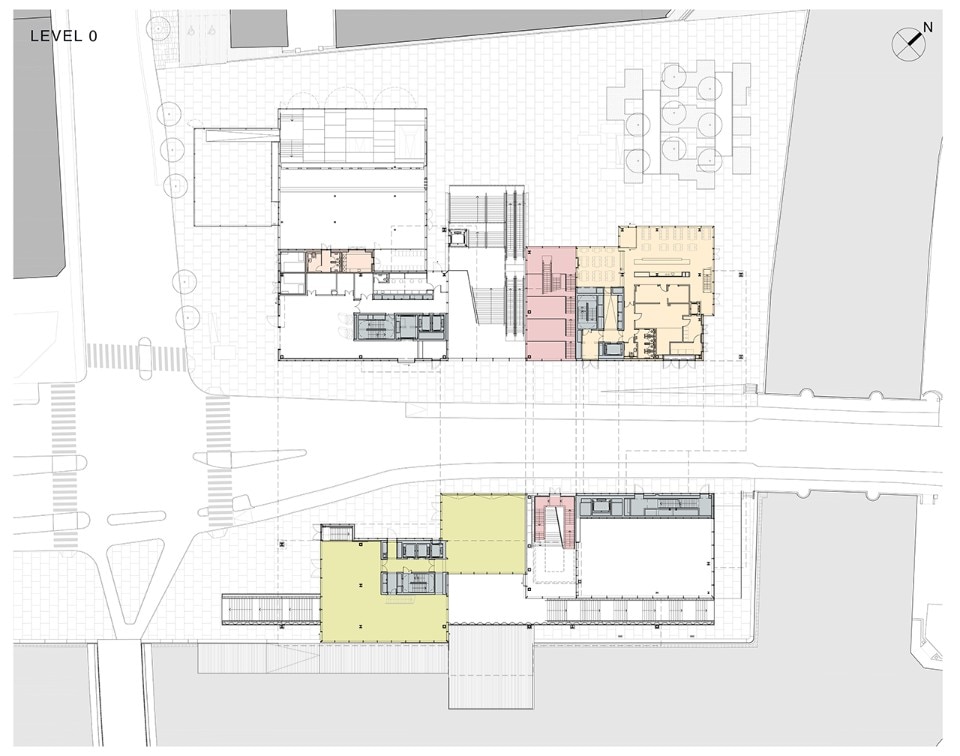

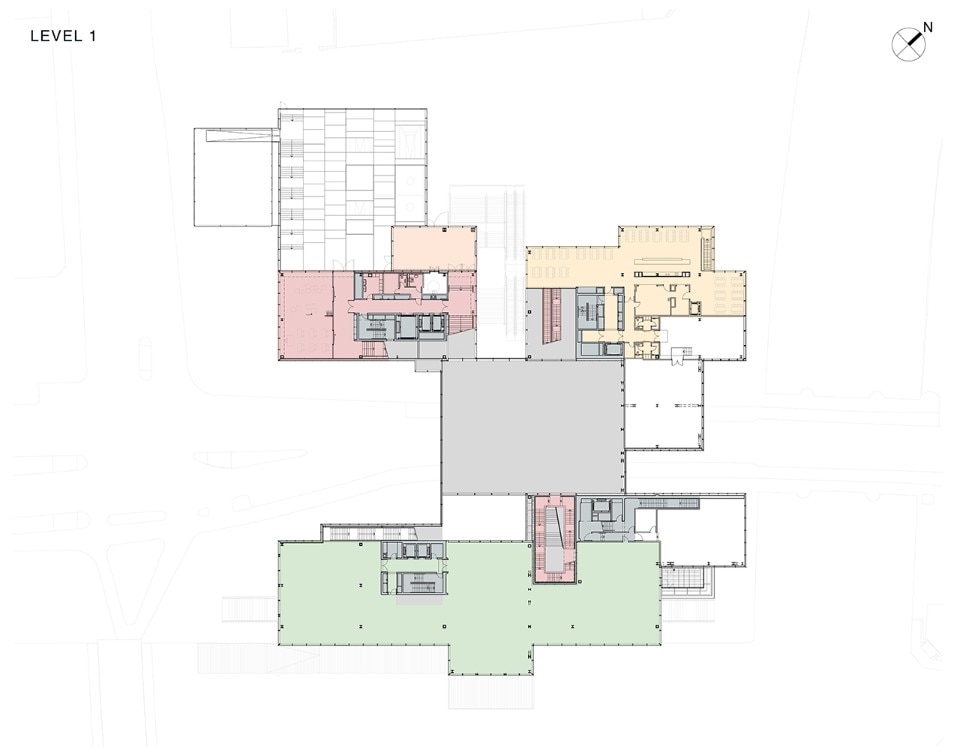

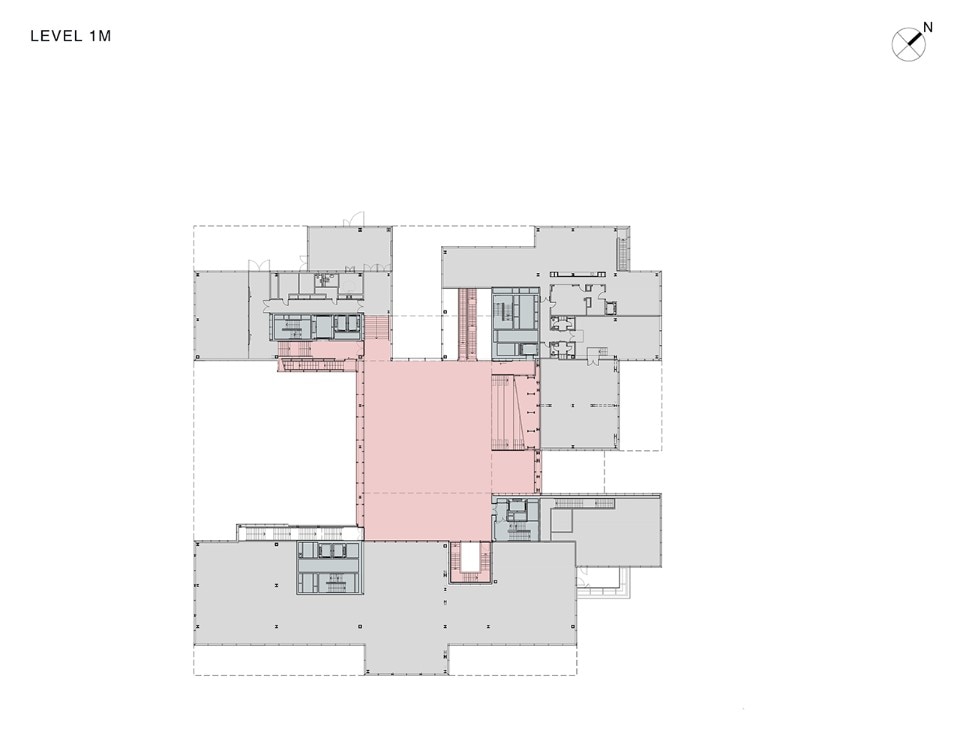

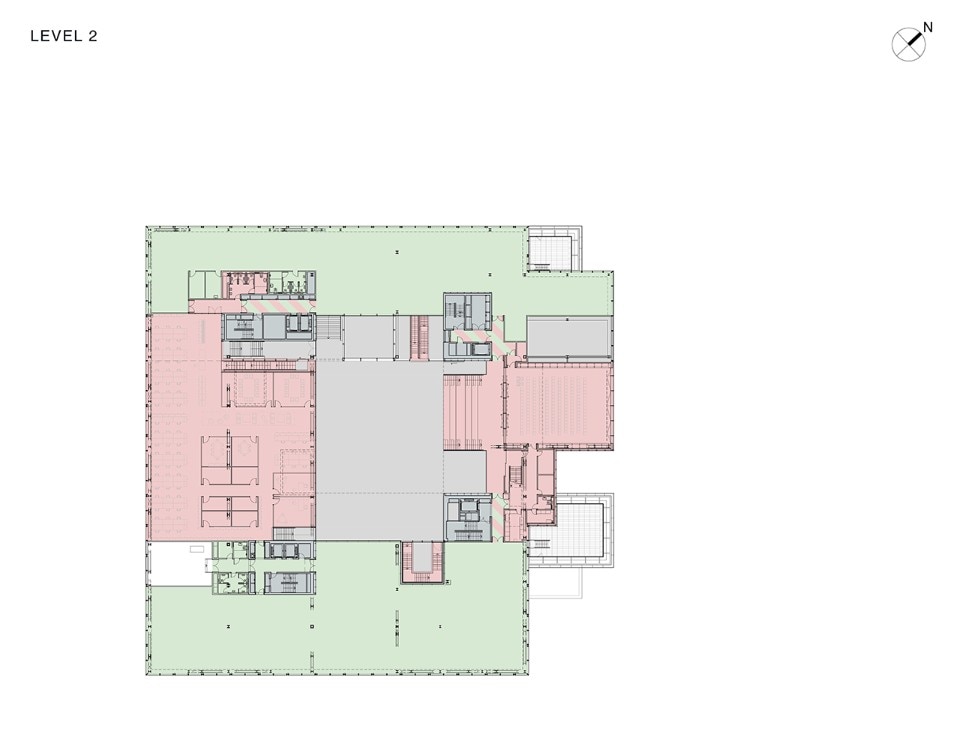

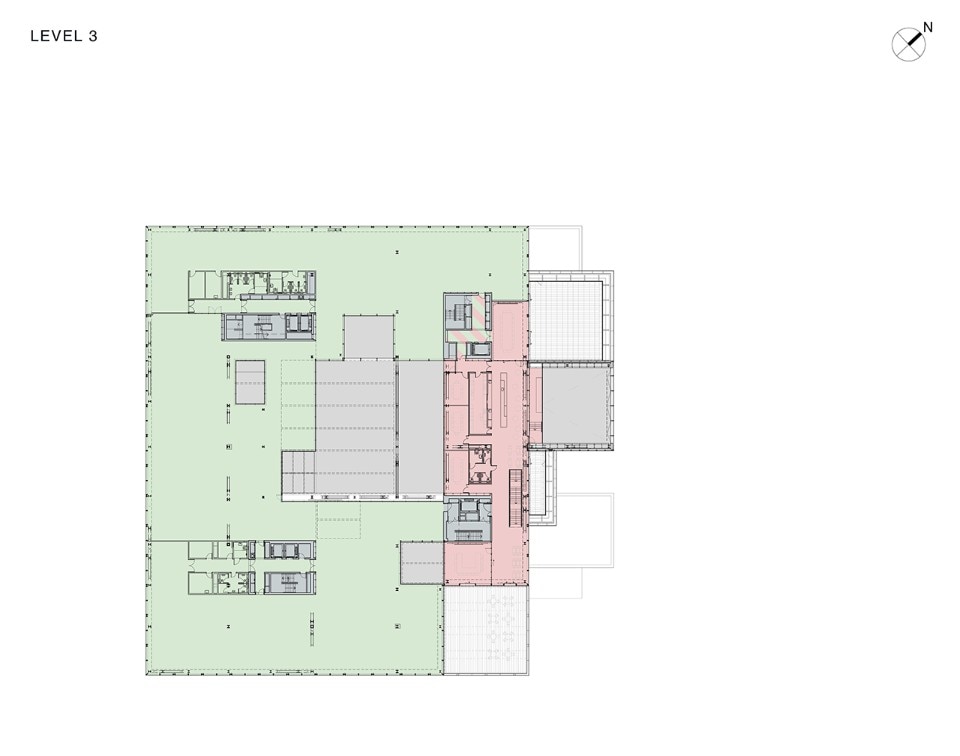

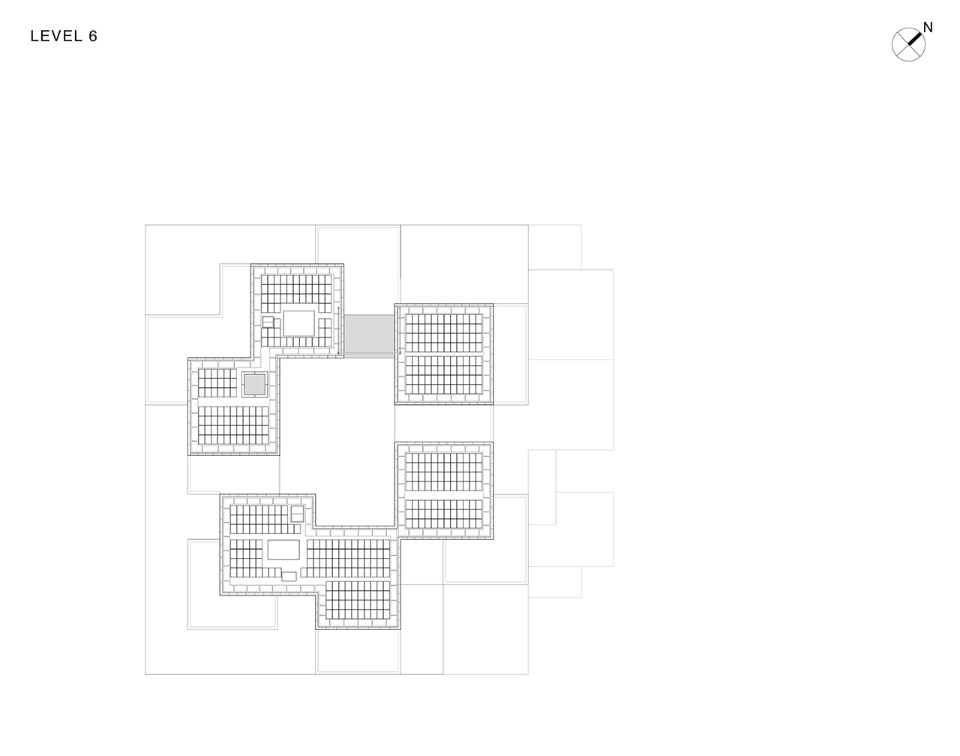

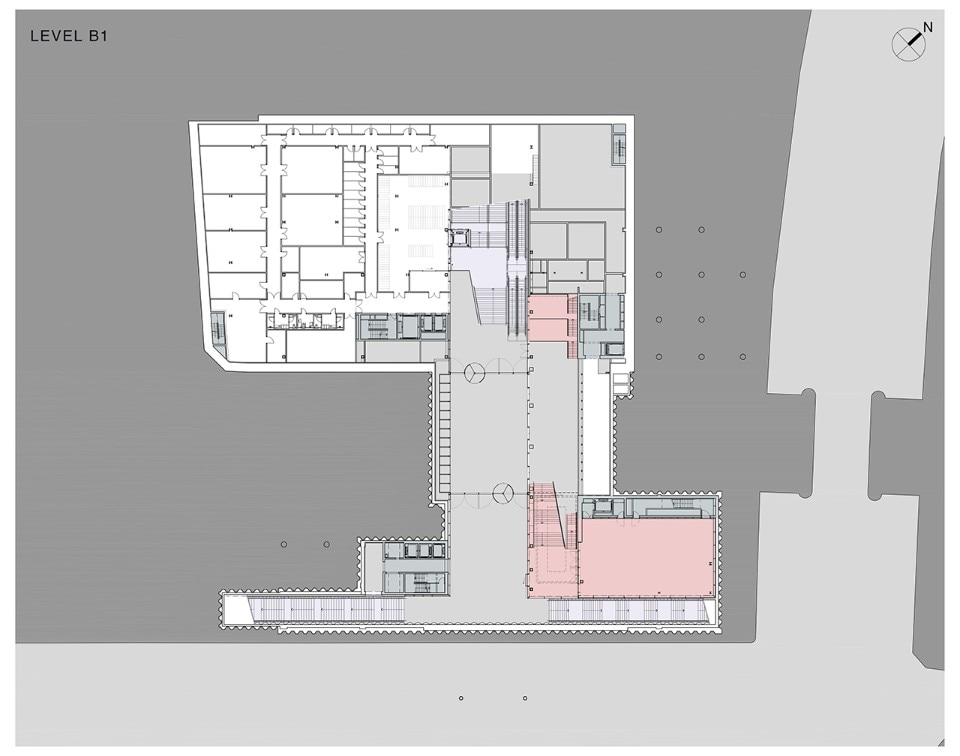

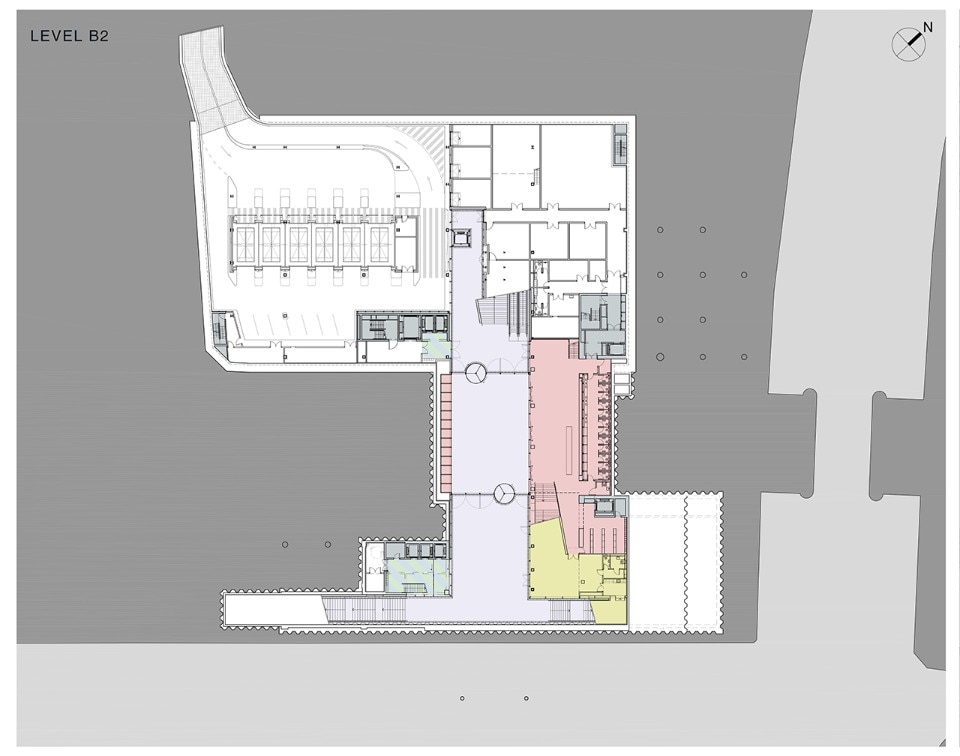

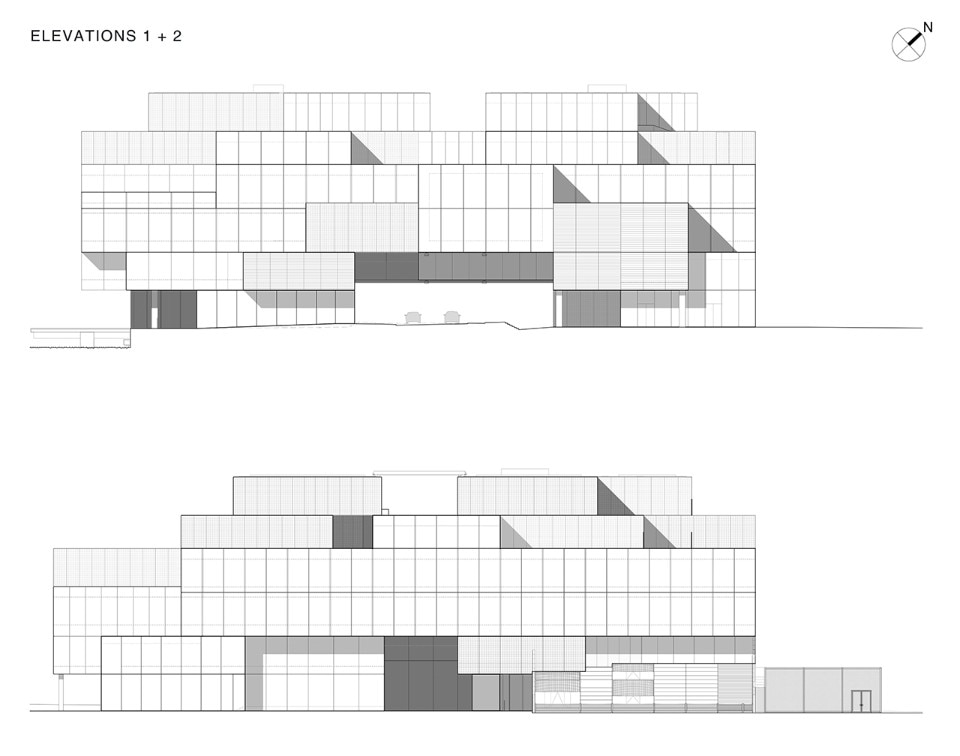

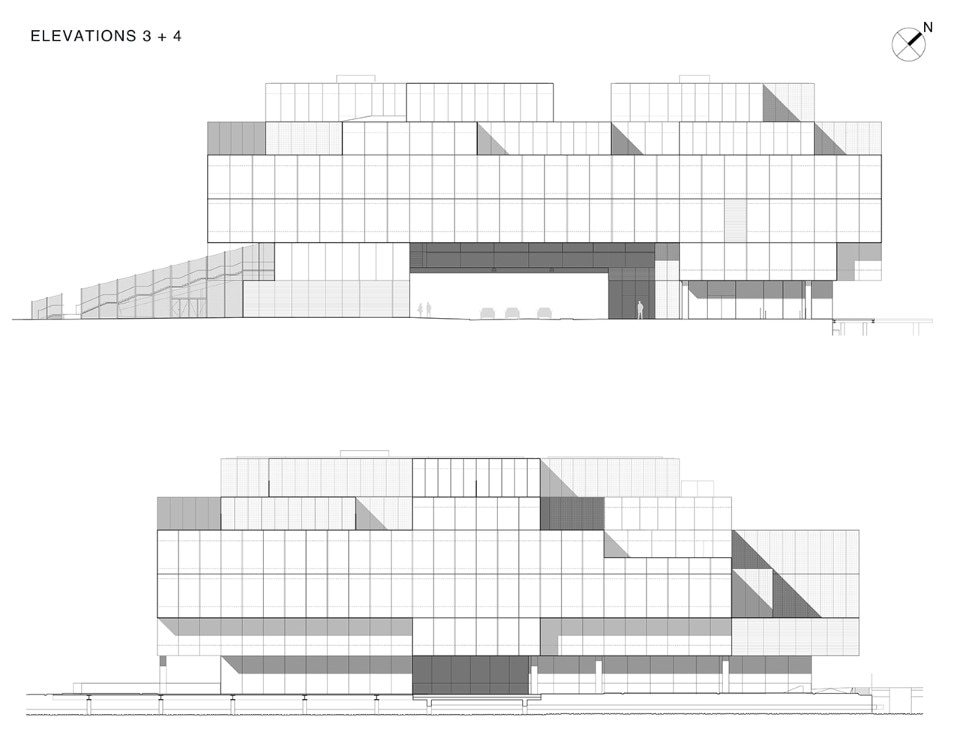

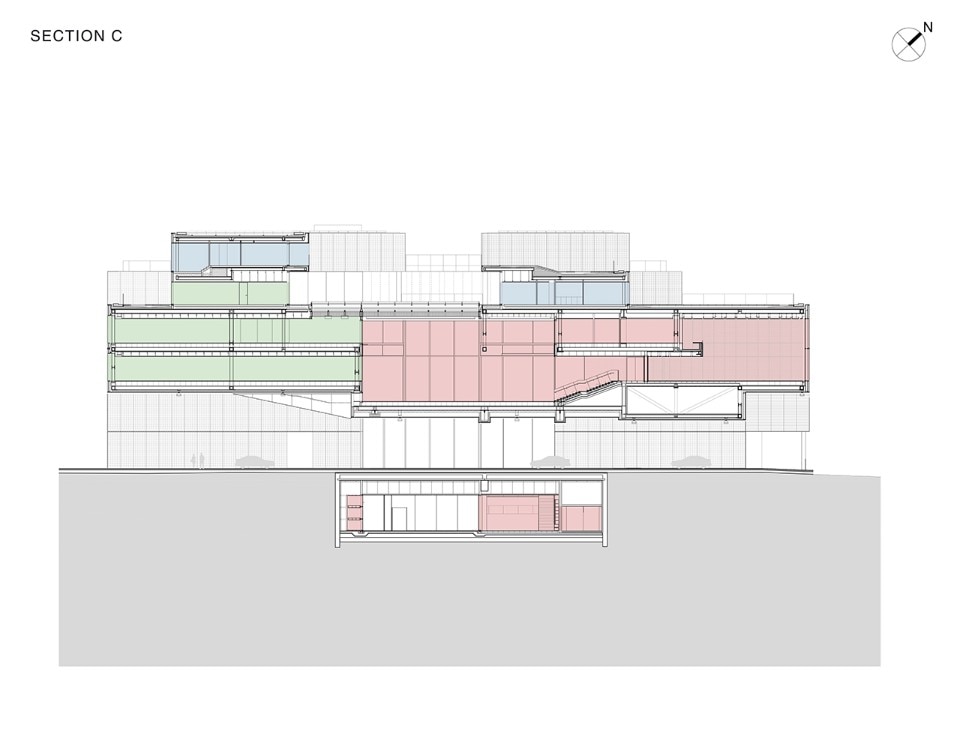

Today Blox has its headquarters in Copenhagen where it serves as an urban condenser of differing realities, among them established companies and start-ups involved in the city’s sustainable development. Started in 2006, the project is the fruit of a public/private partnership and it is the new home to the DAC, the Danish Architecture Centre. Conceived according to the density of the public transport connections it hosts, Blox develops in section both as a drawn plan and as a series of visual relationships between the indoor spaces of the building and its surroundings. Via this operation the visitor clearly sees the simultaneous carrying-out of all the activities contained in the building, from exhibition spaces, offices, and co-working situations to coffee-bars, a bookshop, a gym, 22 apartments and underground parking areas. Exploring and modifying the dynamics of the waterfront (an area of the city currently undergoing great transformation), the building with its nine storeys, is crossed by an urban pedestrian crosswalk and itself serves as a bridge across a ring-road.

View gallery

View gallery

The building as a container for a variety of functions within the city: was this a central theme of the project?

The city already has buildings with mixed public functions on the ground floor and private ones on the upper storeys. Our concept was to subvert this order. Another typical characteristic of Danish urban culture is the overwhelming desire to be freed from traffic – something I can understand as an architect – and to embellish the city, meaning to transform it into a sort of leisure place. There have been times when I feel the city’s lack of original content in an absence of automobile dynamics and congestion. Noise is life, energy, and I don’t see anything wrong with that. Blox is a concentration of functions penetrated by a ring-road and it was designed to be an energetic urban experience, as an inhabited highway intersection.

Blox was designed to be an energetic urban experience, as an inhabited highway intersection.

Speaking of the congestion of functions and references, I wonder if there is a relationship to Dutch Structuralism via, for instance, Herman Hertzberger and his Centraal Beheer.

Dutch Structuralism is a movement whereby spaces are pixelated and connected but, by definition, aren’t polyfunctional. In any case what you’re saying is true: in the last five to ten years we’ve been looking at Hertzberger's buildings. In my opinion there is a great deal of quality in the Structuralist idea of space and it becomes even more interesting when that space is polyfunctional.

You've spent a lot of time in Copenhagen for this project. What do you think of the city?

There are some places that have energy, such as the port where you can see big ships coming into dock. Often, however, there are areas of only coffee shops, bars, and tourists. Instead, along the road connecting the airport to the downtown, there are whole areas of monotonous buildings, all with the same facade, without a single bar or shop. Back in Holland, some years ago we started to deal with the problem of “dormitory” districts. If people want to reside in a quiet place, then they should live in the countryside, but life is found in the city. It's amusing to note that some of the liveliest areas of Copenhagen are among the ones where there is the least amount of designed space, exactly because these are the places where, very suddenly, everything becomes possible.

Is that a critique of Danish urban planning?

It’s a critique of Danish urban planning.

View gallery

View gallery

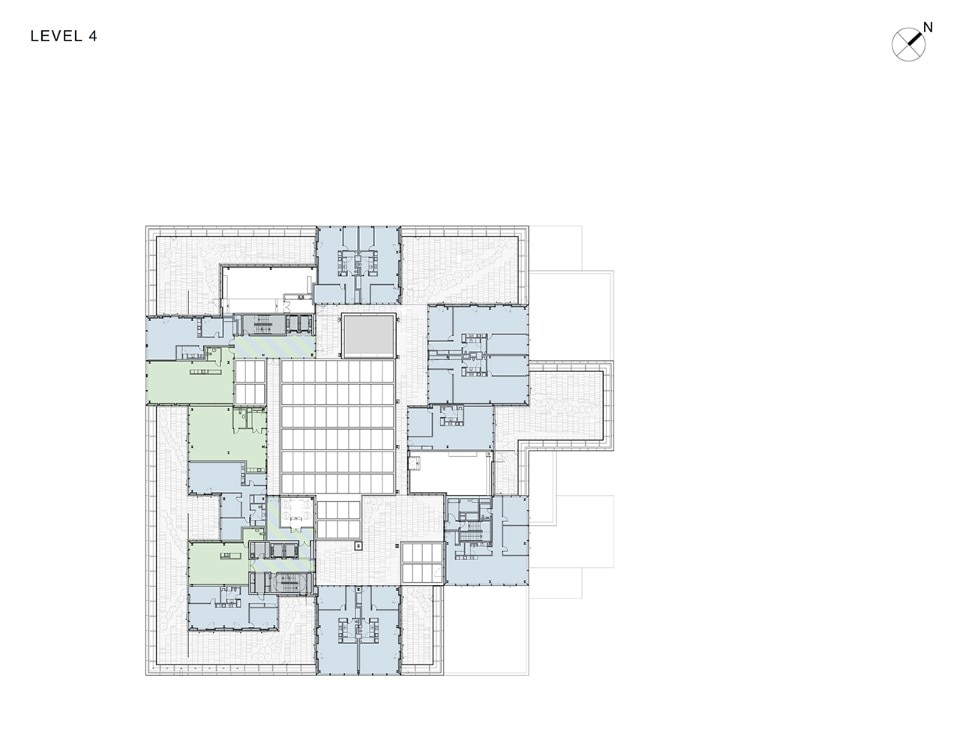

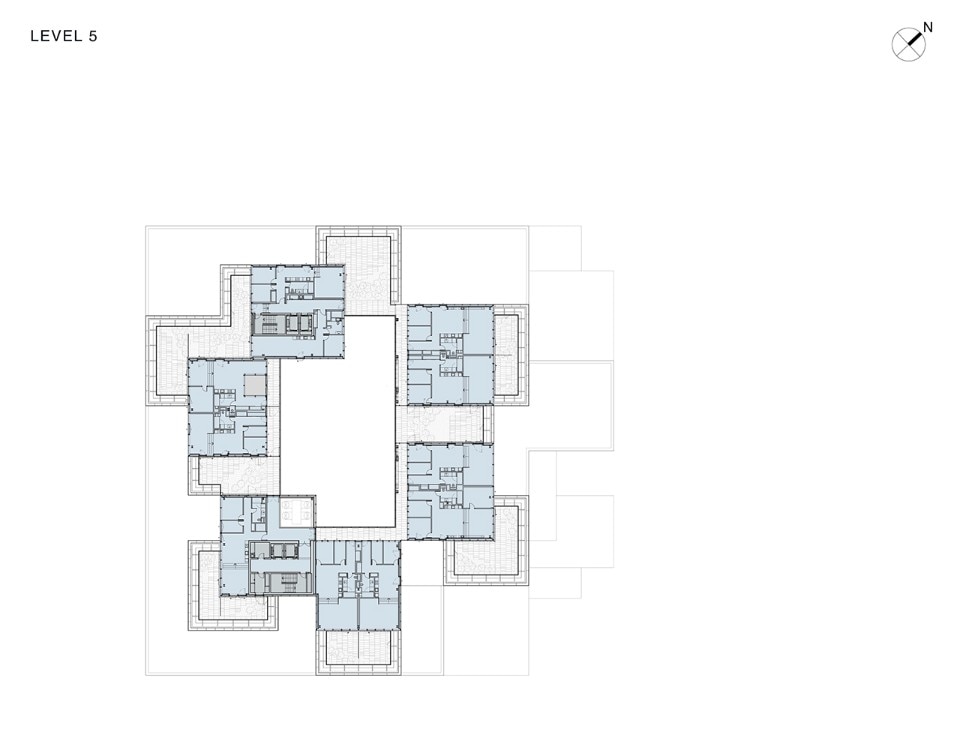

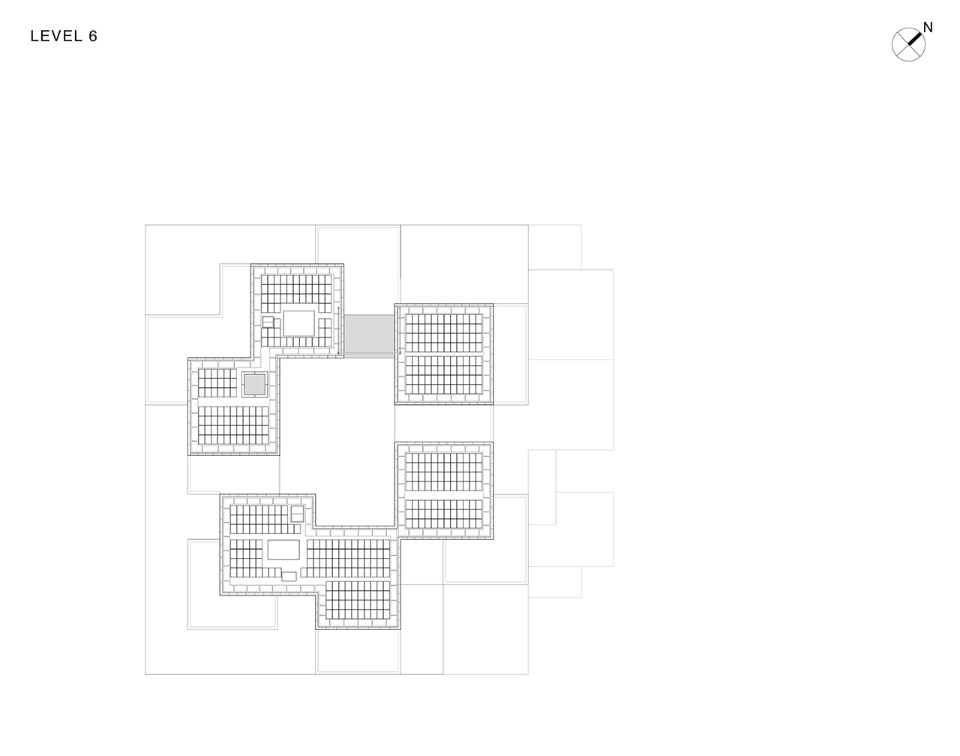

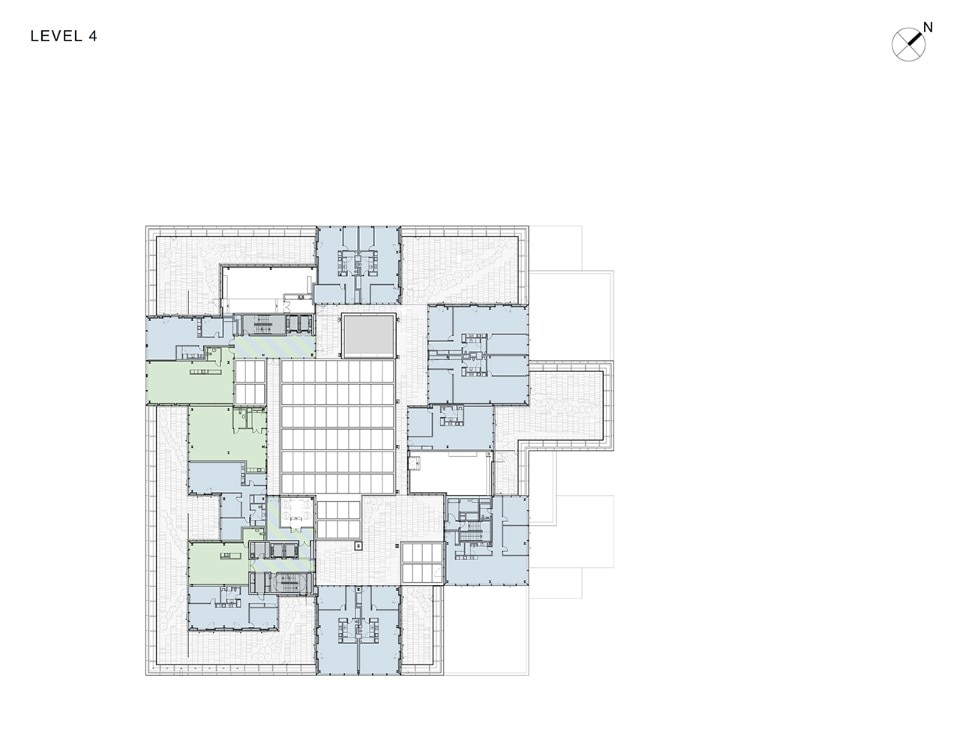

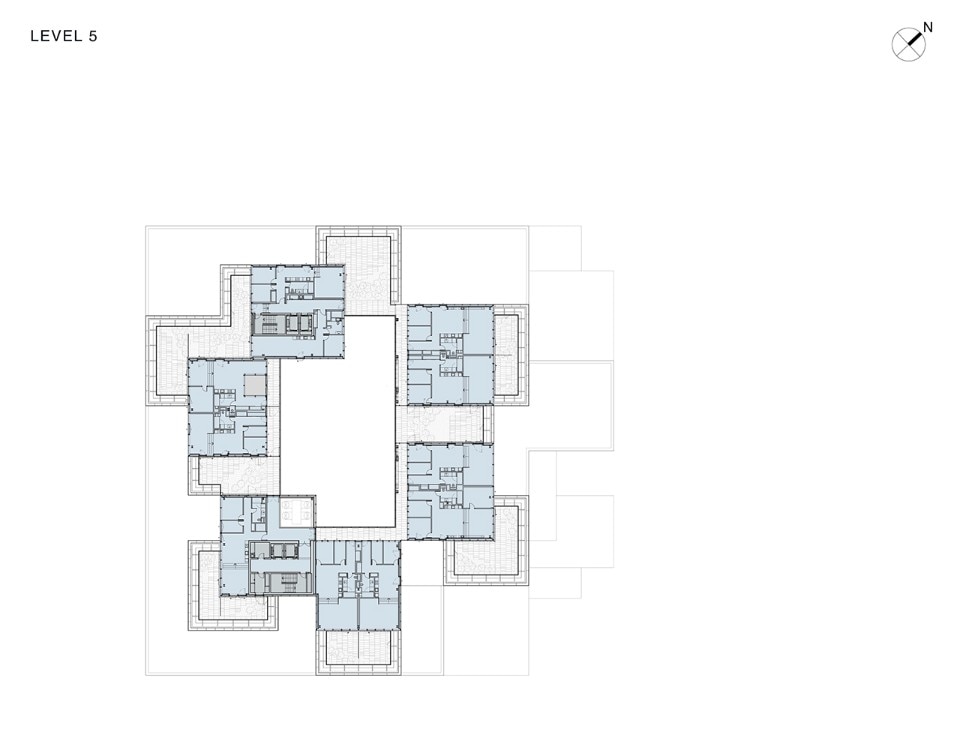

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

2018-03-26_COLORED_PLANS

How did you approach a context in which the influence of Jan Gehl is so very strong?

We met with him while we were moving forward with work on Blox because our client, Realdania, works in tight contact with him. We had a long conversation that turned into debate when Gehl tried to explain his vision for public space to me. We are used to experiment in order to find new opportunities. Gehl was opposed to the urban passage that we had conceived for the building’s interior; he argued that movement and public space should be organised around the building in keeping with Danish tradition. On the contrary, we have carried out an urban passage that serves to connect water and land, leading people to physically feel the crossing of space. The project really addresses the density of the connections that can occur within a public building, between inside and outside.

The project really addresses the density of the connections that can occur within a public building, between inside and outside

Do you find it difficult to talk about sustainability today?

It is difficult only to the degree that each European country has its own system; classifications are neither uniform nor comparable. Danish law has set the highest standards in Europe and, as architects, we know that here we must work – by definition – in an extremely sustainable way. To achieve this, however, I think it’s necessary to design well: if we observe the life of a building, the moment when materials are produced and construction is ongoing is when the most energy will be used. Over a period of 10 years Blox will break even on the amount of energy spent for its construction; therefore, the idea of making buildings with a life span of only 10-20 years makes no sense at all. Secondly, to construct in an environment already as intensely transformed as a city, rather than, say, in the countryside, allows us to contain energy waste and costs. I am very interested in the fact that today we are starting to talk about using materials recycled from the construction industry. We recently completed the renovation of a building for Dutch government offices in The Hague where we used 98% of the discarded material left-over from the demolitions we had affected. Nowadays, in Holland, wastage has value and I think this is really a turning point.

What do you think of co-working?

In the office real estate market, you used to have to sign a contract for a minimum of five years; those are costs that a start-up can't afford. So, in my opinion, the rise of co-working has been a revolution since it allows people to find a workspace even for just one month. Moreover, co-working options multiply the possibilities available to young professionals: to start your own business is complex because so many components are needed, from administration and production to public relations. In these new spaces things are easier because your new neighbours at work might have the skills you’re looking for. Blox is a place for young people.

One can say that half of the project’s challenge was a political process

Some criticism is being voiced that the centre for Danish architecture should have been designed by Danish architects like Bjarke Ingels.

I take this as a compliment: we are being seen as forgers of a new generation of architects. Bjarke is a spin-off of Oma: as a student he worked on the design for the Seattle library while I was making the Casa da Musica in Oporto and I think that now he is doing an excellent job. In any case I think they chose us because they wanted a truly radical project and were aware of the difficulty to realise it within the political context of Copenhagen. One can say that half of the project’s challenge was a political process. It’s true that the building is very Dutch because I didn’t see any need to tie myself to Danishness or to Danish Modernism. Rather, in the last decades, it’s the Danish architects who are looking at Dutch architecture.

- Project:

- Blox

- Program:

- Mixed-use

- Location:

- Copenhagen, Denmark

- Architect:

- OMA - Office for Metropolitan Architecture

- Design team:

- Ellen van Loon (partner), Adrianne Fisher and Chris van Duijn (Project Directors)

- Area:

- 28,000 sqm

- Completion:

- 2018

Tomorrow's energy comes from today's ideas

Enel extends the date to join the international “WinDesign” contest to August 30, 2025. A unique opportunity to imagine the new design of wind turbines.

- Sponsored content