by Davide Montanari

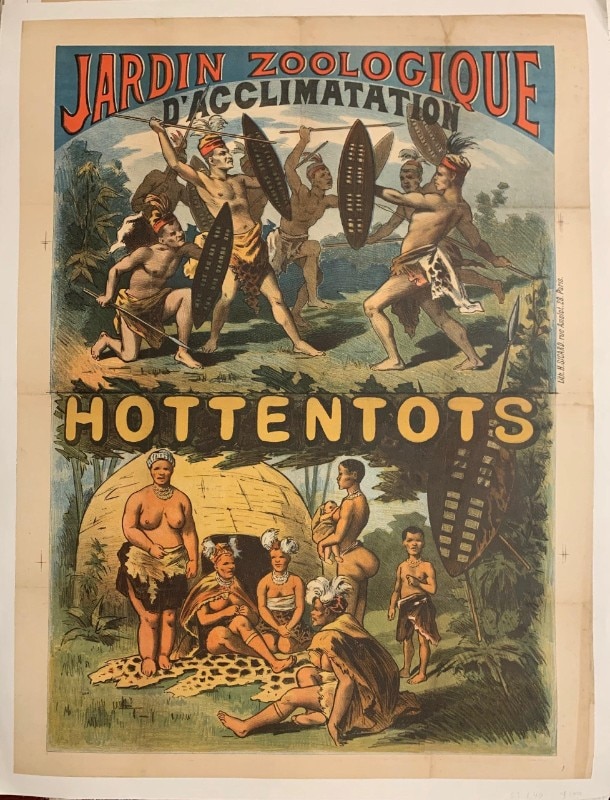

Human Zoos is a volume published in France in 2003. In the anthology - which intercepts the media attention for the first reality shows of those years - the historical practice of exhibiting “exotic” or “wild” human beings is recounted and analysed. This was a widespread custom in the late 19th and early 20th century, at the height of positivism and late positivism: a time when dominant scientific thought regarded white, western man as the apex of biological evolution.

The “others”, human beings from the colonies and often in conditions of semi-slavery, were exhibited as living curiosities or human fossils. The theoretical framework underpinning these practices was the same one that, decades later, would inspire the ethnic museums imagined by the Nazis for Slavic and Jewish populations.

The display of humans as animals is a striking - albeit brutal - way to understand the zoo phenomenon in a broader sense. With the era of modern exploration and colonisation, Europe found itself invaded by an increasing amount of “exotic” species, both animal and plant. These “aliens” are on the one hand sorted according to theoretical hierarchies in scientific catalogues, and on the other hand exhibited in museums. But for live specimens, the exhibition space becomes the zoo.

This phenomenon straddles the divulging of science and the freak show: exotic animals are locked up in cages and shown to a western audience - particularly Europeans, but also Americans - as creatures from distant and inaccessible worlds. In some cases, attempts are even made to construct artificial “habitats” that imitate the species' original living conditions.

One of the earliest examples is the Jardin d'acclimatation in Paris, founded in 1860 with the aim of “acclimatising” exotic animals to European life. During the siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian war, many of these animals were killed and eaten. A century later, John Berger published Why Look at Animals?, a seminal essay in which he interprets the zoo as a place where man looks at the animal reduced to a prisoner.

It is within this controversial framework that a history of architecture develops on the fringes of canonical narratives, but which has been able to generate some of the most unprecedented experiments of the 20th century. In a certain sense, the reconstruction of an artificial habitat that interprets and stages the original, natural one reveals a profound ambiguity, becoming a challenge as much technical as poetic. Complex places, somewhere between simulation and museum device - zoos tell not only how man sees everything that is other than himself, but also provide an interesting contribution on the link between architecture and the representation of nature.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, with the birth of Universal Expositions, zoos took shape as devices for observation, spectacle and education. In this context, architecture played a decisive role, helping to codify the ways in which humans organise their relationship with what is other than themselves. As early as the 1940s, theorist Frederick Kiesler in his manuscript Magic Architecture devoted extensive reflection to the habitats of the non-human, and its rediscovery in the 1960s helped to influence a design current, especially in Austria and France, that started research on the zoomorphic.

Case in point, in this context, is the Penguin Pool designed by Berthold Lubetkin - a central figure of British Rationalism - together with his Tecton group for the London Zoo in 1934. This, together with the subsequent Gorilla House, anticipate the idea of a zoo as a complex architectural machine, exploring the tension between the plasticity of concrete and new ethological needs. Decades later, the same experimental spirit re-emerges in projects such as the Snowdon Aviary, suspended between engineering and vision, or the recent Elephant House designed by Foster + Partners in Copenhagen, which reinvents the zoological pavilion as a space for coexistence.

The selection of projects proposed here crosses different periods and geographies: from the Casson Pavilion at the London Zoo, where zoomorphic forms meet Brutalist suggestions, or the large tropical aviary realised at the Jurong Bird Park in Singapore. It is a narrative in episodes about some of the transformations that have affected zoo architecture between the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. Architectures, technological ecosystems, hybrid spaces that take the form of narrative tools: structures that mediate between species and spectator, spaces designed by humans that allow themselves to be questioned and shaped, at times, by non-human bodies and behaviour. The episodes collected here testify to the controversial attempt to design cages and containers, but at the same time scenographies, imagery and technical devices that attempt to mitigate captivity according to the new concerns related to animal rights.

Gorilla House – Berthold Lubetkin e Tecton, London Zoo, 1932

The Gorilla House, designed by Lubetkin and the Tecton Group in 1932, introduces a renewed lexicon within architecture for zoos. This is not simply a container for exotic animals, but a statement on the modernist ethos: structural rationality and functional clarity to generate a habitat capable of declaring its artificiality, positioning the animal in a legible architectural scene.

The use of reinforced concrete and the plastic composition of volumes recall the formal lesson of Le Corbusier, but the project reveals an all-British tension toward the public and pedagogical dimensions of architecture. In this “house for others,” the ambition to humanize space, even when the guest is not human, is reflected, in which a reinforced concrete organism translates the Corbusian ideal of the “machine à habiter” into a “machine à montrer” for other forms of life.

Snowdon Aviary – Cedric Price, Lord Snowdon, Frank Newby, London Zoo, 1962–1965

The result of an unprecedented collaboration between a visionary architect, an experimental engineer, and a court photographer, the Snowdon Aviary marks a moment of discontinuity in architecture for postwar zoos. Cedric Price does not design a building, but an aerial, suspended infrastructure: an architecture in tension, composed of angular steel and aluminum limbs wrapped in a thin skin, capable of accommodating flight as a spatial principle. The aim of the project takes place thanks to the common desire to subvert the logic of the cage: cables, tubes and nets compose a threadlike landscape, technological and dynamic. A scenography with permeable, walkable contours, designed for the gaze and movement.

Casson Pavilion – Sir Hugh Casson, London Zoo, 1962–1965

In the heart of the London Zoo, the Casson Pavilion emerges as one of the finest examples of postwar brutalism, where materials such as stone, concrete, and glass are confronted with raw, primitive geometry and roughness that define the building's massive body.

Designed by Sir Hugh Casson between 1962 and 1965, called upon to redesign the former home for elephants and rhinos, the project chooses to adopt the grammar of Brutalist forms combined with zoomorphic formal suggestions. The intention of the project is intertwined with the desire to offer animals an environment that would respond to the new ethological conceptions of zoological spaces, proposing an architecture where the material language becomes an integral part of animal imagery.

Now decommissioned, it remains as evidence of a season when architecture was searching for a balance between function, symbol and monumentality.

Monkey House – Hascher Jehle Architektur, Stoccarda Zoo, 1956 (ristrutturata)

Established after World War II as a pavilion for large primates, the Stuttgart Zoo's Monkey House has undergone a profound architectural rethink over time.

The renovation by Hascher Jehle Architektur transforms the original 1956 layout into a space in which transparency emerges as the founding principle of the design.

The basis of the intervention is linked to the desire to overcome the enclosure as a punitive device, opening instead to a relational vision between species. The grammar of Brutalist forms survives in the essential volumes, but is lightened by the use of glass and the flexibility of spaces. In this reinvented pavilion, architecture filter space between animal behavior, human perception and environmental responsibility.

The Waterfall Aviary at Jurong Bird Park – Singapore, 1971

Jurong Tropical Park, opened in 1971 and now closed, enclosed an ecosystem where exuberant vegetation is intertwined with the rhythms of the avifauna that inhabit it. A metal mesh, rarefied, almost a thin invisible membrane supported by a slender metal structure, a permeable boundary containing a nature expertly constructed to recreate a perfect tropical habitat, dominated by a tall artificial waterfall.

The architecture merely orchestrates flows, the reflections of light on plant and animal bodies, the ever-changing perceptions. Here the container disappears, allowing the relationships of the animal environment to emerge.

Elephant House – Foster + Partners, Copenhagen Zoo, 2008

Conceived in the early 2000s, the design for the Elephant House is the result of a collaboration between the Copenhagen Zoo and Foster + Partners, where close collaboration with biologists and animal behavior specialists, reflecting a desire to move beyond the idea of the zoo as a space of mere exhibition to conceive of an environment that generates multiple relationships.

Two lightweight glass and steel domes cover a terrain shaped in sections, articulating separate environments in a balance between ethological needs and climatic comfort. The architecture retracts, becomes topography, letting natural light, porous materials and the curvature of the ground design the experience. Here the idea of habitat is not simulated, it is constructed, in a continuity between form, function and ecological respect.

Elephant House – Markus Schietsch Architekten, Zürich Zoo, 2014

Markus Schietsch for the elephant house in Zurich designs a continuous, open, edgeless volume where animals and visitors share a continuous, light-filled space. The wide glulam roof, supported by a lattice structure with complex geometry, defines a fluid interior environment that emulates the topography of a wet savanna. Completed in 2014, underlying the project is a long listening phase: ethologists, landscape architects and engineers guided the architecture toward a new balance of form and biology. Light, moisture and ventilation are orchestrated as active elements of the composition. In this project, form does not impose: it accommodates, interprets, returns. A work that reinterprets in a contemporary key the responsibility of man towards the species he hosts.

Paris Zoological Park – Bernard Tschumi Urbanistes Architectes + Véronique Descharrières, Parigi, 2014

The renovation of the Paris Zoological Park coincides with a gesture of rewriting: no longer the monumental ark of the colonial era, but an environmental device that models the reciprocal relationships between environmental milieu and animal life. The project, entrusted to Bernard Tschumi in collaboration with Véronique Descharrières, is distinguished not only by the richness of the program, but also and above all by the open spatial layout, centered on interconnected ecosystems, in which architecture retracts to leave room for the process of continuous co-evolution between species.

The Grand Rocher-a monument of zoological modernism from 1934 and the starting point of the project-is preserved as a symbolic anchor point and integrated into a renewed spatial narrative, and around this core, the park is configured through an articulated sequence of immersive environments. The idea of the project is rooted in the call to rethink the park not only as a place of preservation, but as a critical experiential environment. It is an architecture of attention, where visitors do not simply look at animals, but are immersed in an environmental context designed to put the position of the human back into perspective.

Antwerp Zoo – Studio Farris, Antwerp, 2017

In the heart of Antwerp's historic zoo, founded in 1843 and among the oldest in Europe, Studio Farris carries out an intervention in 2017 that reflects a refined integration of historic preservation and a contemporary architectural language. Commissioned by the KMDA (Koninklijke Maatschappij voor Dierkunde van Antwerpen), the project responds to the need to renew the exhibition and service infrastructure while preserving the site's identity character. The pavilion, whose design emphasizes a mastery of composition and clarity of design, is articulated through a succession of transparent, wood-clad volumes, establishing continuity with the morphology of the park. The building assumes the role of a relational device: it does not impose its presence, but accompanies the gaze, filtering the landscape, orchestrating a measured choreography that involves the visitor, the animals and the context that hosts it. It is a threshold architecture, making porous the boundary between the subject who observes and the subject who receives the gaze.

Panda House – BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), Copenhagen Zoo, 2018

In 2018, the Copenhagen Zoo commissioned the Danish studio BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) to design a new panda enclosure, which stands out for its strong symbolic component stemming from the shapes inspired by the Yin-Yang symbol. The project is part of a context of growing attention towards the creation of environments that are able to meet both the needs of the animals and the educational needs of visitors.

The intention is to create a synthesis between aesthetics and function through an environment capable of reflecting a holistic vision of the interaction between man, nature and culture. The composition - while remaining at the service of the protection and welfare of animals - through its curvilinear profile and a repertoire of forms inspired by the organic world wants to lead towards a reflection on our relationship with other living beings. The enclosure thus becomes a metaphor for a space that seeks to accommodate the visitor's body and the animal body in a single habitat, a place that stimulates an empathic connection between the species it houses, in its various forms and degrees, a zoological landscape that promotes a more conscious relationship between nature, space and the public.