Each of us is formed professionally and personally by a succession of environments that nurture us, turning into layers of experiences, friendships and places. The geography travelled by David Chipperfield has taken him on a rich and varied journey from a childhood in the Devonshire countryside, through the doors of the Architectural Association and the offices of Richard Rogers and Norman Foster as a young architect in London, to Japan, Germany and Italy (pivotal locations in his career), and also to Spain, his refuge from it all.

These are merely anchor points, bases for innumerable excursions that have all left their mark – Mexico City, Shanghai, Agra in India, Seoul, Iowa and beyond. Japan instilled an appreciation of simplicity and the elevation of what is normal – both elements became a leitmotiv for his practice. In Italy, he had the opportunity to think bigger, to work with stalwarts of the design industry and to oversee architecture’s most popular event, the Venice Architecture Biennale (2012). In Germany came his first big break (1997) with the Neues Museum, a project that has defined 20 years of practice.

Climate change and societal crises are enforcing new geographies. Through involvement in the Architects Declare movement and Fundación RIA – and now with Domus – Chipperfield is seeking practical ways to redress ills. “We still struggle to think how we might make any significant contribution to the crisis. Well, it is no longer on the horizon; it’s absolutely upon us,” he says. “Many architects, especially younger architects, are doing really interesting work and trying to find new ways of practice. My guest editorship at Domus is addressed to them.”

The West Country

David Chipperfield was born in London in 1953, but the West Country became his childhood home, first on the family farm in Devon and later at boarding school in Somerset. “Memories are unreliable; they’re exaggerated; we rewrite them. But I can remember very distinctly the physical places of my childhood,” says Chipperfield. He recalls the intense physicality of rural life growing up in a “Noah’s Ark” populated by cattle, pigs, chickens and crops, which gave him not the inclination to be an architect, but certainly a sensitivity to place. “You become very tuned to physical stuff. In the city, it always belongs to somebody else. In the country, it somehow belongs to you,” he says. “It sounds overly romantic and probably too sentimental, but growing up in Devon on a farm certainly impressed me and embedded in me the enjoyment of the tangible.”

It wasn’t until his teenage years at the Wellington School in Somerset that architecture began to emerge as a career path. “The reason I became an architect, I think, had to do with when I went to school,” he says. “I wasn’t particularly academic, but in a boarding school you have to become good at something, otherwise you get trampled on.” And so he dedicated his time to sports and art, spending weekends in the art room painting and drawing thanks to an encouraging teacher. “That was the accident of how I became an architect.”

London

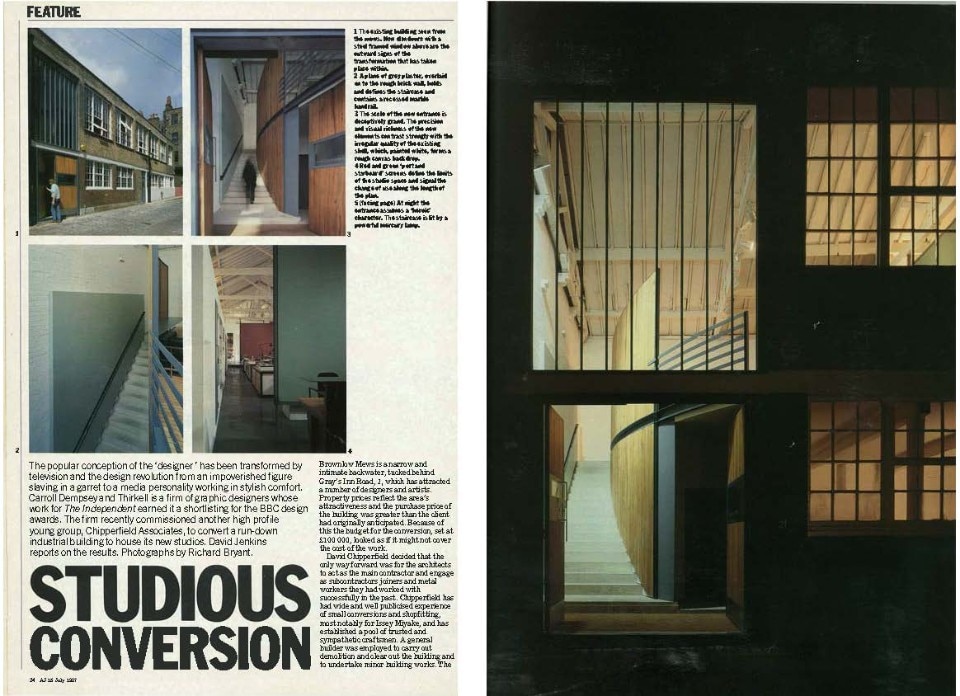

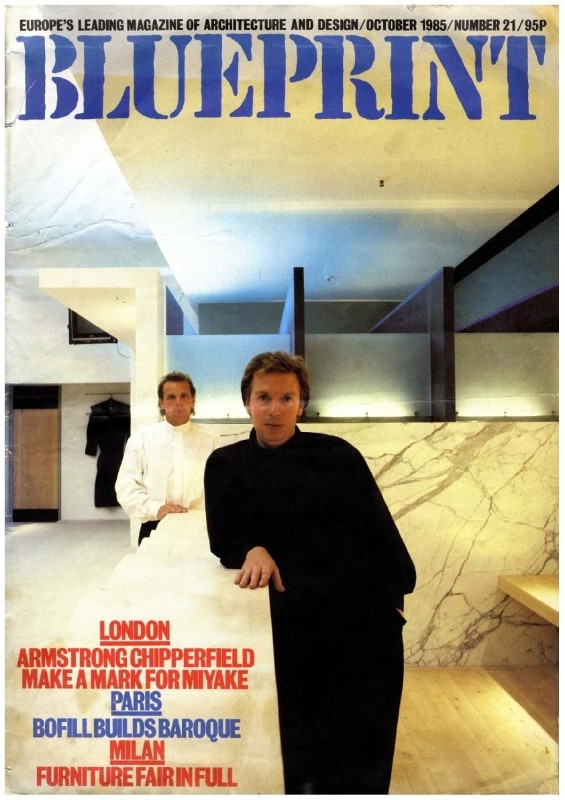

Drawn away from the countryside to London, Chipperfield enrolled at the Kingston School of Art and then the Architectural Association School of Architecture, graduating in 1977. “I was always fascinated by London. Coming from the country, I was desperate to be part of something sophisticated,” he remembers. “You feel inferior coming from a rural environment, so I think I was dazzled – and I still am dazzled to some degree – by the chaos and the wonderful complexity of the unknown dimension of the city.” Emerging from architecture school, he took on stints in the offices of Richard Rogers, Norman Foster and Douglas Stephen before setting up his own practice in the capital in 1985. His first project, an interior, came from the Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake for a store on London’s Sloane Street. Subsequently, a series of projects in Japan led to an international outlook, but London has continued to be his home and the centre point of his professional life, with a new studio on The Strand arranged around a vast model workshop containing dozens of projects, from a theatre to apartments.

His British projects range far and wide in scale and use, from his first architectural commission – an extension to the 1950s home of the photographer Nick Knight (1990, plus another in 2001) – to a studio for the sculptor Antony Gormley (2003) and most recently the pair of brick-clad hexagonal Hoxton Press apartment towers on the Colville Estate (2018) in east London. While his practice is lauded for its striking cultural buildings – Neues Museum in Berlin (2009), the Jumex in Mexico City (2013) and Zhejiang Museum of Natural History in China (2018) – there are relatively few chances to experience them on quite the same scale in the UK. “All of these exercises are to do with working outside of England,” he notes of the course of his emotional geography. “We never really worked in England. We still don’t.” But there are of course The Hepworth Wakefield art museum (2011), the River & Rowing Museum in Oxfordshire (1997), the Turner Contemporary in Margate (2011) and a recent extension to the Royal Academy of Arts in London (2018).

Japan

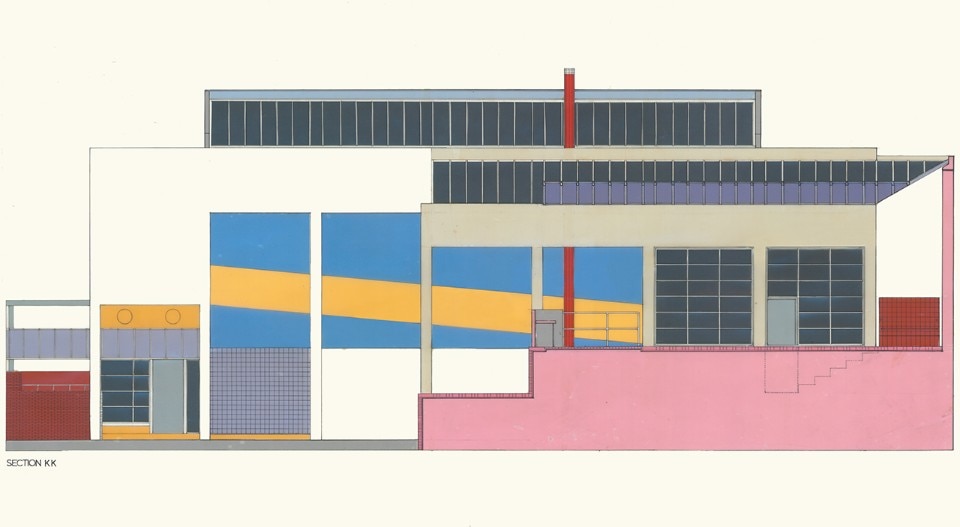

Before any of these projects came a productive period in Japan. Chipperfield’s relationship with Issey Miyake led him there to design a suite of stores. He soon discovered that he was afforded architectural opportunities that “would have never happened in the UK.” A trio of mid-sized commissions kick-started his career in the early 1990s: Toyota Auto Kyoto, the Gotoh Museum in Chiba and the Matsumoto Corporation headquarters in Okayama.

“Those five or six years were incredibly formative. Japan was the second part of my education really. The experience was quite profound,” he says. “In a way, it was the beginning of my career. Without that, I don’t think it would have started.” Here, he became friends with the acclaimed modernist Tadao Ando, and absorbed a way of working that involved “simplifying things, taking normal things and making them special” – something that has informed his practice ever since. “Instead of making everything spectacular, you find the essential qualities of something and try to express that,” he says of the process he learned. “And I would say that’s a sort of mantra for my practice.” In 2013 Chipperfield was awarded the Praemium Imperiale in recognition of his work, just as he was beginning to design the Inagawa Cemetery in Hyogo (2017) in Japan. The chapel and visitor centre is bound by rose-tinged walls with carefully arranged apertures, making it a serene and generous space for reflection at the foot of the Hokusetsu mountain range.

Italy

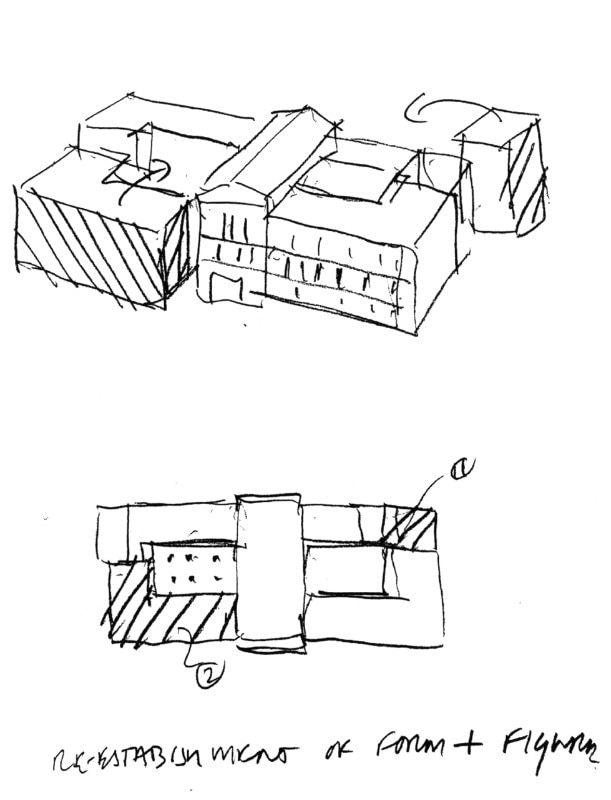

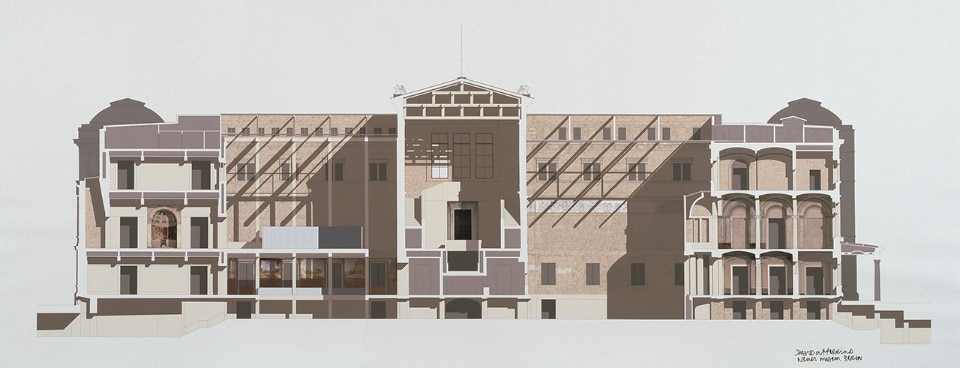

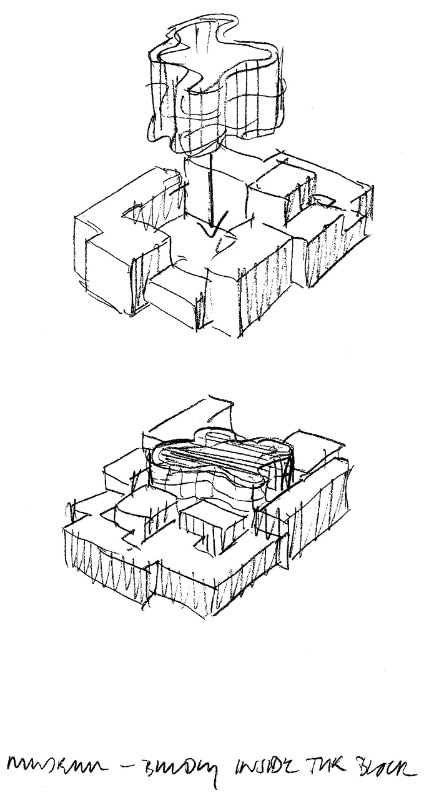

Italy offered Chipperfield’s practice its first opportunity for growth by means of abundant architectural competitions in the 1990s. A succession of wins include an extension to the San Michele cemetery in Venice; the Museo delle Culture (Mudec) in Milan (the results of which met with the architect’s reprobation); a courthouse in Salerno; and a natural history museum in Verona. These projects allowed the practice to scale up from house extensions and store interiors to grander projects. “The second phase of our office was to do a lot of competitions in Italy,” remembers Chipperfield. “During the 1990s, there were many well-organised competitions. And we won about four in a row.” The Mudec (2015) is the

only one of these to be fully complete, with San Michele in Venice awaiting its third and final phase, and work in Salerno and Verona still ongoing. “I wouldn’t say these were great professional experiences,” says Chipperfield. Nonetheless it was a pivotal time for the young practice.

He opened his Milan office in 2006, and there have been contributions not only to architecture such as the new campus in the works for the University of Padua, but to design, with the Moka espresso coffee maker for Alessi (2019), as well as products for Artemide, Driade and B&B Italia. “The Italian relationship has always been important,” he says.

In 2012, he was appointed exhibition director of the Venice Biennale of Architecture. The theme he chose for that year’s Biennale was “Common Ground”, which will become the basis of discussions featured in Domus throughout 2020. “Already at that time, I was trying to say that there are issues that have more to do with the practice of architecture than with the competition of architects amongst themselves,” he says. “I wish to be an advocate – not of architects competing with one another, but of architects showing a consolidated front. I want to show what we share and not what not what separates us. Everybody is concerned with similar issues, so why not talk about the common ground we need to achieve with society?”

Germany

The appointment to renovate Neues Museum in Berlin in 1993 was a “life-changing experience” for Chipperfield. “I was lucky to find myself in the middle of a city that was reimagining itself. I became part of the reimagination,” he says. His Berlin office opened in 1998 and its staff has now outnumbered that of the London office. Work on Museum Island in the Mitte district occupied the Chipperfield team there until it reached completion with the opening of the elegant colonnaded James-Simon-Galerie in 2018.

Its slender concrete supports echo those of the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach am Neckar (2006), awarded with the Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize in 2007. Next, the practice will take on the refurbishment of the Neue Nationalgalerie designed by Mies van der Rohe. “Germany is so respectful of architects,” says Chipperfield of the reception of his work. “I’ve been someone who has promoted the importance of Berlin, its architecture and the city. I’ve been reasonably outspoken, and the fact that I’m engaged is appreciated, I think. I’ve been invited to dinner with Angela Merkel, whereas I would never get invited to dinner by British politicians.”

Galicia

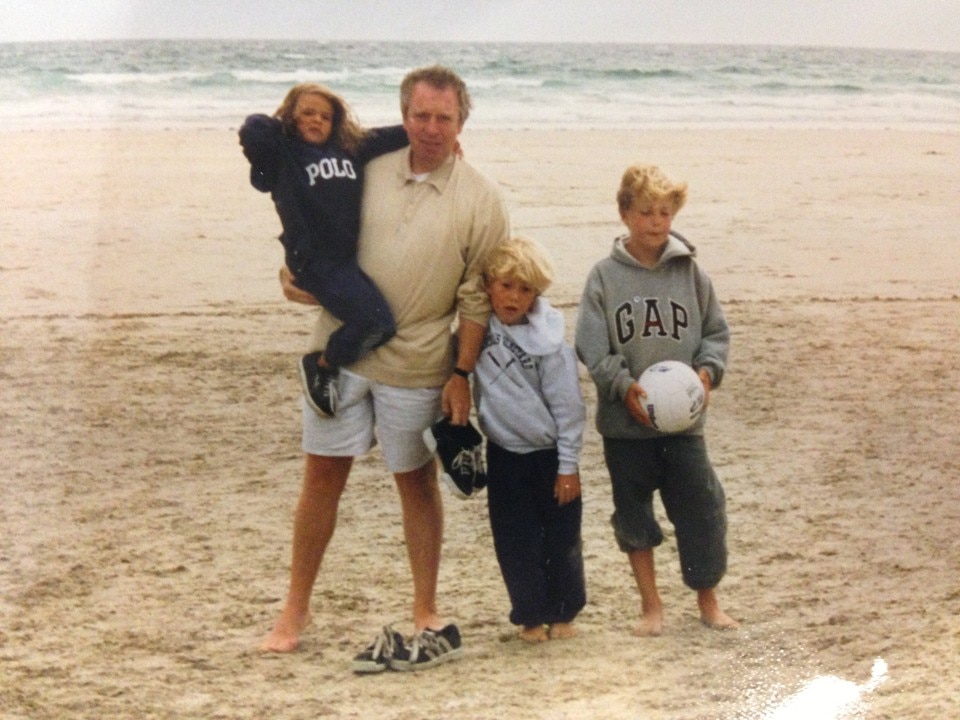

If London is one bookend to the emotional geography at play, Galicia is its mate on the other side. Chipperfield and his family have been visiting the Spanish region for almost three decades. Recently, they have been escaping London to a bright white seafront property that ramps directly onto the beach. “Galicia has been the family’s refuge for 27 years. It puts us back into a normal, real community,” he says, adding that it is the quality of life that draws him back repeatedly to Galicia.

It’s the antithesis of the social climate he finds in the UK, embroiled as it is in its departure from the European Union. “Galicia is one of the poorest parts of Europe, with good resources, high quality of life based on a sense of community, and an attractive environment. When I compare Galicia to the UK, I see a lesson to the consumerist world we’ve invented,” he says. “We’re going to have to learn how to deal with less consumption, and abandon it as a primary form of entertainment.”

In 2016 he set up the Fundación RIA (Rede de Innovación Arousa), which advises local government on the planning and conversion of the Galician area of Arousa. It’s an independent foundation and Chipperfield’s way of putting some of the earnings of his practice into “doing good” in a community he values so – an act that has recently been acknowledged by local newspaper El Correo Gallego, which presented him with the Galician of the Year Award 2019, a prize instituted by the Grupo Correo Gallego. “The foundation’s been a way by which I try to address the concerns and societal responsibilities that I think architects should be involved in,” he explains.

“The problem is, we’re at the end of the food chain, so we only get involved if we’re asked. I’m trying to make a societal contribution. I don’t sit here waiting for someone to come and say, ‘Would you do this?’ Rather I step forward and say, ‘We’d like to do this.’ It would be nice if promoting the common good were a bit more embedded in normal practice.”