This article was originally published on Domus 1036, June 2019

From 3D printing to robotic fabrication, cutting-edge technologies have already been adopted by the global construction industry. These seemingly futuristic tools, however, will find a foothold in our everyday lives as anything but exotic. Instead, even the most radical technologies will be absorbed into our daily routines as practical methods of DIY repair and small-scale renovation. In the process, digital innovation may spur a return to a premodern ethos of community sharing and collective labour, as residents network their printers to produce new designs together or reuse architectural debris to collaborate on future projects. These behaviours are the social infrastructure through which advanced tools will be welcomed into our lives, and they are an overlooked yet vitally important part of today’s design conversation. The urban future, we might say, will be performed with our friends and neighbours.

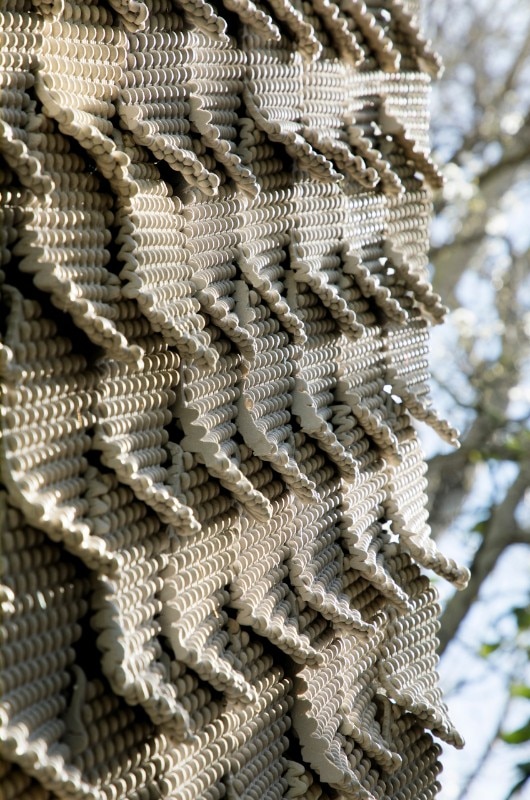

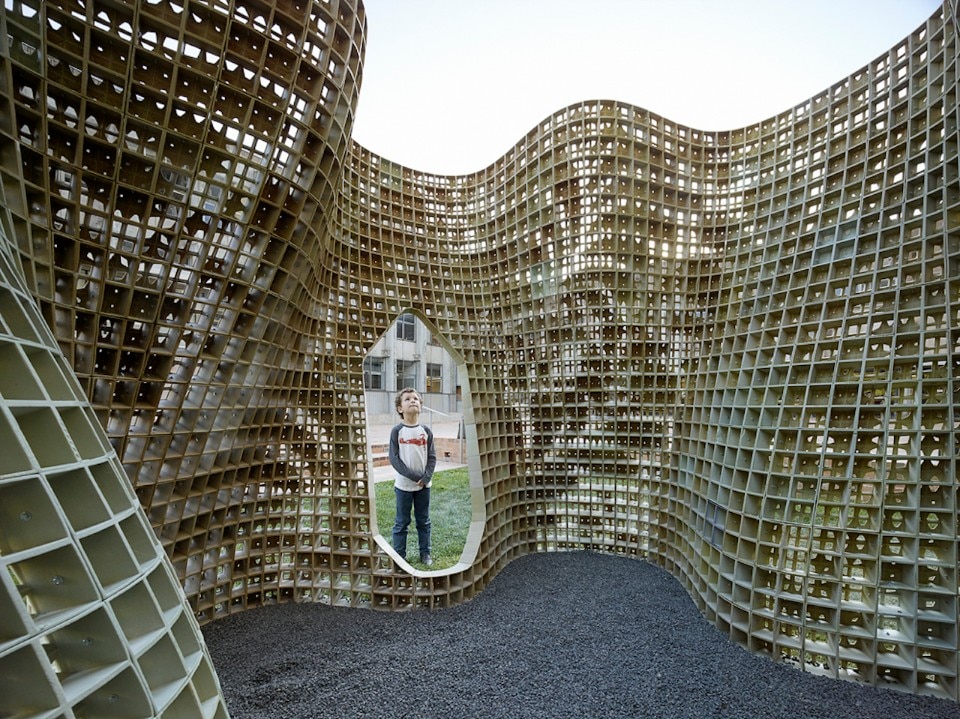

Consider the Star Lounge, a recent project by Emerging Objects, a Berkeley-based design startup founded by Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello. The Star Lounge explicitly emphasises the social context of 3D printing. Rael and San Fratello’s approach was to use a hive of desktop printers, each tasked with producing a small, assembly-ready modular panel. The duo described this approach as using a “BotFarm”, in which one printer’s individual output would, in effect, be worthless, but, taken together, amounts to a new, distributed construction technique.

There is power not only in scale, but in social distribution.

The Star Lounge brings with it a whole world of implications for how neighbourhoods might work together in the near future to repair or construct vernacular architecture. The work of Emerging Objects can be seen as a social prototype for how communities will labour to produce architecture in a technologically collective fashion. As Rael explained to me, Emerging Objects has often found that the technical limits of different printers already necessitate a distributed, networked approach: one lab’s printer can only manage a specific material, for example, or produce work at a particular scale, whereas another lab, several buildings away or in another city entirely, can manage another. Brought together, they can produce the compo- nents necessary for what we might call emerging architecture, where the assembly of a building becomes a highly choreographed social event, combining small-scale crafted products from different groups.

Although architecture-ready 3D-printing technology remains prohibitively expensive to run and maintain for low-income communities today, a kind of architectural Moore’s Law dictates that, soon enough, architecture-capable printing facilities will be economically viable for low-income neighbourhoods. Local repair economies will function not unlike the Star Lounge conceived by Emerging Objects. Imagine a networked farm of 3D printers churning away in a dozen houses somewhere, producing small components for neighbours and friends. Like sewing new patches onto an old sweater, this vision of spatial maintenance suggests that the built environment does not need to be reinvented from the ground up in an age of 3D printing. Instead, it will be incrementally transformed, day-to-day, even on an on-demand basis.

For a group known as Matter Design, this should be taken much further: futuristic urban tools will require ancient human behaviours. A research and fabrication office with partners based in Michigan and Massachusetts, Matter Design’s work suggests that the key to the future might be lurking in the mists of urban history. Their project Cyclopean Cannibalism, for example, combines high-tech geometric fabrication with premodern, hands-on craft.

Grounded in research performed by studio principals Brandon Clifford and Wes McGee, the group uses the word “cyclopean” to indicate large blocks of masonry that they hew into geometrically irregular, prismatic shapes. These units are then stacked or interlocked into puzzle-like walls that deliberately recall ancient Incan engineering. The resulting work combines technical research, modular geometry and the clever reuse of discarded building materials, all with an eye towards disadvantaged communities learning new (or, as it happens, ancient) forms of construction.

As Clifford revealed to me, their research – equal parts archaeology and structural engineering – soon made it clear that the Incas weren’t quarrying new stone every time they needed to build an architectural space; rather, they were using what he called “a selection technique” to choose random, loose boulders, or they simply “cannibalised” existing buildings. In fact, Clifford added, “Since industrialisation, we are the only civilisation that does not cannibalise our architecture. For instance, St. Peter’s Basilica quarried their stone from the Colosseum. It was once just standard practice.

But, today, the building industry is addicted to new materials. We like to standardise things and to know what’s inside of them.” This addiction to standardised materials, Clifford suggests, has not only affected the formal possibilities of contemporary architectural design; it has also led to a socio-economic scenario in which cutting-edge architecture is ironically so standardised that it can be out of the reach of vernacular, everyday construction techniques. People literally cannot afford to build their own houses out of modern materials.

Instead, they have easy access to non-standard materials: to architectural debris or previously used components and parts. “In today’s urban context,” the group warns, “we generate unprecedented quantities of waste. There is an impending crisis hinging on how we deal with this debris, specifically from buildings.” Cyclopean assembly – cannibalising architectural debris for new structures – might be able to change that. Clifford brought my attention back to the Incas, to show how even today’s ruthlessly digital design culture shares a great deal with ancient construction techniques: “The way that the Incas worked is much more akin to the way that we can operate today through digital algorithms. They were just working through rule-based logics that could accommodate random shapes to produce new architectures. To us, that sounds much more like digital architecture than something Mies was working on.”

“It’s a way of thinking, first and foremost,” Matter Design partner Wes McGee added. McGee suggested that their puzzle-like process of architectural assembly is best seen as “a procedural act”, a precise sequence in which “understanding a very specific order of assembly is the key to understanding how it all goes together”. Architecture becomes a sequence, an algorithm, a set of instructions – not unlike the modular social event of Star Lounge by Emerging Objects.

Indeed, for Clifford, the way forward might be to look back, not to the nostalgia of Arts and Crafts, but much further, deeper into archaeological prehistory, to find new ideas for the future of fabrication. Digital design can mine practical inspiration from ancient means of assembly, even as designers and builders themselves can discover tricks and tools from the premodern past.

Geoff Manaugh is a Los Angeles-based design writer, and author of the New York Times bestselling book A Burglar’s Guide to the City.

Opening picture: Star Lounge (2015) by Emerging Objects is a structure composed of hexagonal elements in PLA, a thermoplastic polymer derived from natural sugars. Each colour expresses precise structural qualities and every block is numbered to facilitate assembly