If overcrowding and intensive building development are specific traits of urban areas—where the pressure of settlement and scarcity of free land are addressed through the “skyscraper” typology, with minimal footprint and maximum vertical extension—today even once-remote non-urban localities, previously untouched by waves of urban migration, are surrendering to the imperative of densification and high-rise construction imposed by mass tourism.

This is the case of Zermatt, the iconic mountain resort at 1,600 meters above sea level at the foot of the Matterhorn, which—with its 6,000 inhabitants swelling to 40,000 in high season—constantly battles against a cyclical hospitality implosion, fueling a real-estate market that is increasingly prohibitive and elitist.

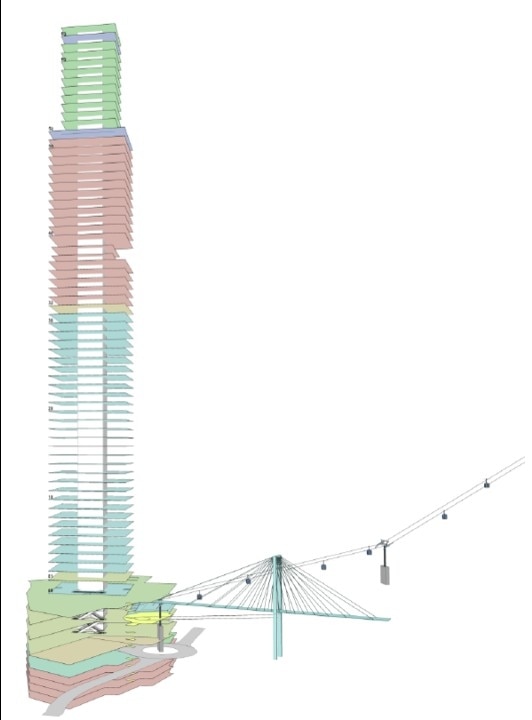

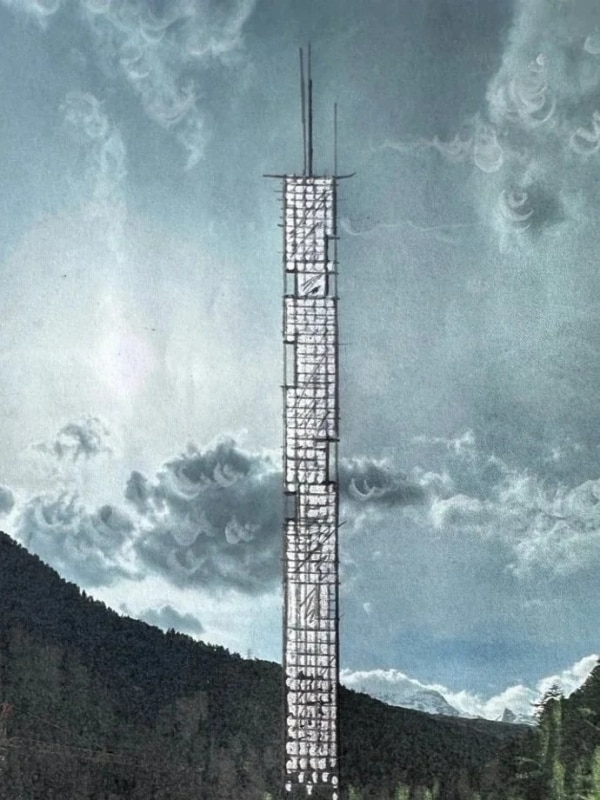

Offering a response to the chronic housing shortage and the heavy urban strain of the Alpine village is entrepreneur-architect-designer Heinz Julen, who has proposed importing from the metropolis the typology of the high-density, low-environmental-impact skyscraper: this is Lina Peak, a 260-meter-tall multifunctional tower rising like a steel-and-glass needle inserted into the valley and pointing towards the sky.

The building, whose concept was recently presented, could inaugurate in the region a new urban season aiming high (not only in altitude but also in terms of territorial marketing): the complex, set to become the tallest skyscraper in Switzerland, would host 550 housing units over 65 floors, standing as a manifesto for a renewed tourism management strategy based on concentration rather than dispersion of hospitality services.

The complex, a candidate to become Switzerland's tallest skyscraper, would house 550 accommodations on 65 floors, posing as a manifesto for a renewed tourism management of the area.

A symbolically disruptive gesture that radicalizes the densification trend found in mountain resorts and ski stations worldwide (from Chengdu to Aspen, though with lower built heights and located in valley-floor settlements or high-altitude cities), and one that follows the path already traced in Switzerland by several proposals—either unbuilt or recently realized: from the unfinished “227 Schatzalp” in Davos (the 105-meter tower designed by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron in 2003) to “7132” (the 381-meter skyscraper designed by Morphosis Architects in 2015 near Peter Zumthor’s Vals Thermal Baths), up to the completed “Tor Alva” in the village of Mulegns which, “settling” for its 30 meters, holds the world record as the tallest 3D-printed tower.

Beyond records and good intentions, the proposal is conceptually far from free of contradictions. On the one hand, reduced land consumption, the concentration of services and infrastructure, and potentially high environmental performance reflect a desire to limit sprawl and shrink the ecological footprint. On the other, the “metropolization” of the Alps carries the risk of landscape distortion, alongside the technical challenges—and substantial costs—of building in such specific climatic and ecological conditions. It also raises the specter of speculative real estate ventures vulnerable to collapse should tourist flows decline, operational expenses surge, or future marketing strategies redirect the masses of skiers toward other, higher peaks (and towers).