This article was originally published on Domus 945, March 2011

In a fine little book of his autobiographical notes[1], Tomaso Buzzi writes about Sebastiano Serlio: “Would it be worth my while to study him and write about him? It would be like part of my destiny, for I have studied him since the beginning. From his book I have drawn details of doors, buildings and theatrical sets and I have borrowed from his projects. Then I bought his work and after I lent it to Guido Visconti, Duke of Grazzano, I never got it back and he died at El Alamein. Later his sister Nane returned it to me and then she gave me a beautiful edition of it that was part of the Landau-Finaly, De Marinis, etc. library” (31 December 1967).

This excerpt of seemingly banal memories is a summary of Buzzi’s whole eclectic world. The backdrop is his classical education, constantly nourished by such a passionate interest in ancient architects that it squeezed out all attention for his contemporaries. Besides Serlio, his masters were Palladio, Scamozzi, Piranesi and Ledoux, and these “encouragers of doing” formed the basis of his library and his architectural imagination. A monograph that was belatedly dedicated to Buzzi’s work contain much well-written commentary on his “timeless” references[2].

In 1956 Buzzi bought the monastery from the Franciscan Order. Isolated in the Umbrian countryside, it takes its name from the marsh plant scarza with which Saint Francis of Assisi made himself a bed there

His most interesting move was to transfer this suspended sense of time to the theatre, “the real way, the only legitimate way in architecture, to become inspired, to borrow from and refer to forms of the past, modes of expression, the use of materials, mannerisms, et cetera, without falling into the trap of reconstructions.” At 20, he undertook the operation of redrawing in pencil numerous Italian paintings from the 14th and 15th centuries, eliminating all human and animal figures and leaving the piazzas and rooms empty.

He even carried out this erasure of presences from the architectural scenery of himself from 1934 onward, when he radically changed his professional direction with the restoration of a Palladian villa in Maser, the property of Marina Volpi di Misurata. From then on, Buzzi began a phase of high living, and was welcomed into the most elite circles of Italian society – high nobility and finance – where he became the darling of interior decoration for prestigious residences. He experienced these conditions with a life-saving dose of humour and detachment, sometimes punctuated by the melancholy of a man who feels alone in the midst of many people.

Above all, Buzzi possessed a lucid sense of self-criticism when it came to his monumental body of work and his exit from the official world of architecture. His proven anti-Fascist leanings were held quietly, without the ostentation that many chose to flaunt after the Liberation. This background explains the mnemonic recollection of his training as seen in his “stone autobiography”, La Scarzuola, which filled the latter part of his life.

In 1956 Buzzi bought the monastery from the Franciscan Order. Isolated in the Umbrian countryside, it takes its name from the marsh plant scarza (sedge-grass) with which Saint Francis of Assisi made himself a bed there.

Buzzi turned the monastery into his home, which included his archive of books, drawings and objects. He began to build a make-believe city in the former vegetable gardens, complete with seven interlocking theatres, some open-air, others indoors, with “more variety, ideas and fantasy than in any other”. A place of enjoyment and retreat, it is a fossil that does not allow other presences.

“At La Scarzuola... all is a theatre and when a person (and there are many) asks me what plays I will stage, I answer that for me, silence is the star of the show.” It is a sort of revenge that Buzzi takes on his “unlucky destiny”, shared with Serlio and Piranesi, of having non of his architectural inventions built.

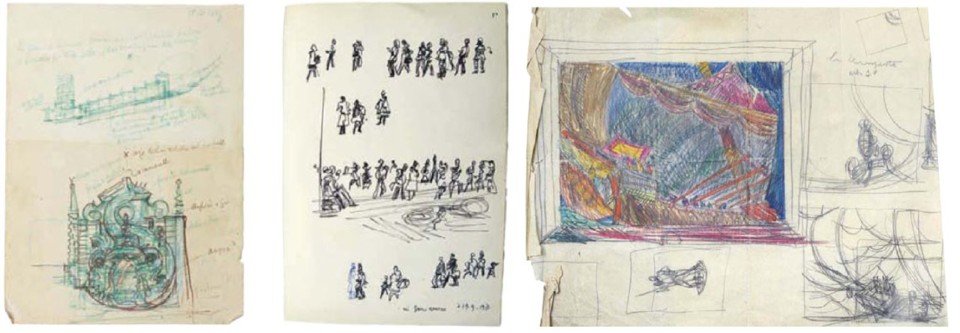

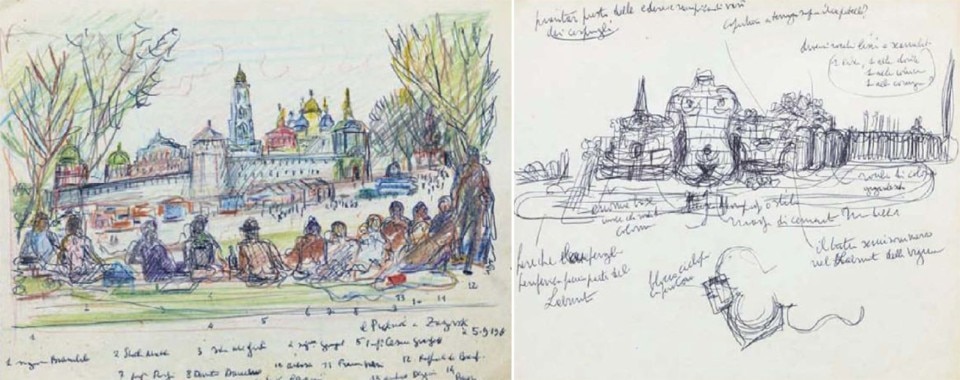

His sketches represent the powerful common denominator of his multifarious interests, as well as revealing an amazing natural artistic talent. Often drawn with a ballpoint pen (quick drying) and sometimes annotated with coloured pastels, they showed the place and date on the right. The innumerable sheets of paper of all sizes contained in the archived boxes at La Scarzuola are proof of an impressive daily production and an automatic high-speed execution that portrays lively moments during parties, performances or travels. The written words contribute, underline and describe with similar swiftness and without grammatical worries. His habit of superseding chronology led Buzzi to return to his sketches after some time, modifying and adding to them with different pens.

This background explains the mnemonic recollection of his training as seen in his “stone autobiography”, La Scarzuola, which filled the latter part of his life

The notes in the margin on a sketch for the eastern border of his fantasy city reveal the concreteness of his project: evergreen shrubs of laurel and box, arbutus and ivy, cypresses and reflection ponds represent the hope for eternal life. Meanwhile, the coppice wood of turkey oak that surrounds the silent theatre at La Scarzuola reminds us in its growth cycle of the alternation between life and death.

Tomaso Buzzi (Sondrio 1900 – Rapallo 1981) was part of Milan’s neoclassicist movement, a member of the editorial staff at Domus, and art director of Venini until 1934. He subsequently devoted himself to elite clients, the furnishing of Italian embassies around the world, and the refurbishment of the Arsenale in Venice. From 1938 to 1954 he taught Drawing from Life at Milan Polytechnic.

With thanks to Marco Solari, heir of Tomaso Buzzi, for kindly granting the drawings reproduces here.

- 1:

- Tomaso Buzzi, “Lettere pensieri appunti”, 1937-1979, curated by Enrico Fenzi, Silvana Editoriale, Milan 2000

- 2:

- Alberto Giorgio Cassani, “Antichi maestri, anime affini”, in: Alberto Giorgio Cassani (curated by), “Tomaso Buzzi. Il principe degli architetti 1900-1981”, Electa architettura, Milan 2008