Frank Owen Gehry, born Ephraim Owen Goldberg, is one of the most prominent figures in contemporary architecture, often referenced when talking about “starchitects”, or about those architectural works that go beyond their intended mandate, becoming works of art in themselves. From the shores of Lake Ontario to his early career on the West Coast, and culminating in the Pritzker Prize awarded in 1989, Gehry's style has accompanied and represented some of the structural social and technological changes from the post-war period to the present day. Through thematic explorations and a chronological synthesis extracted from the digital archive, we revisit the key moments in Gehry's career, giving voice to those who have written about him in Domus until the present day.

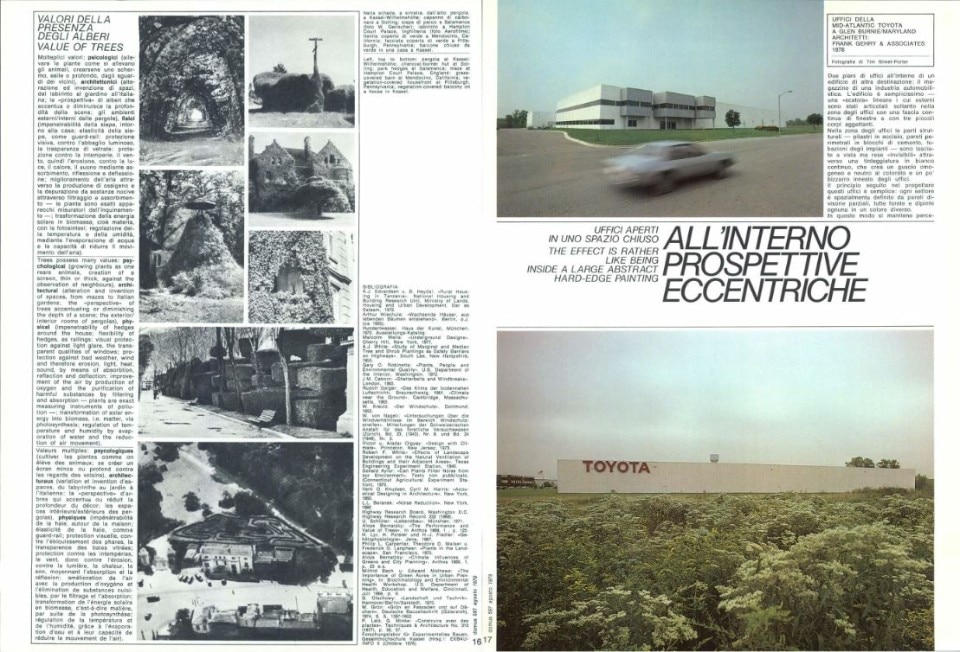

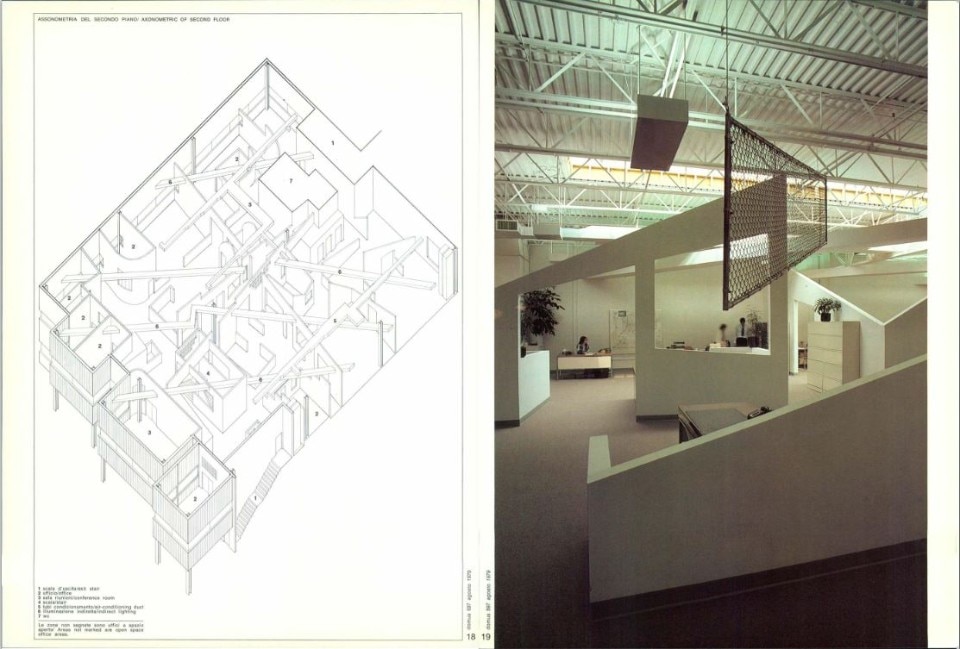

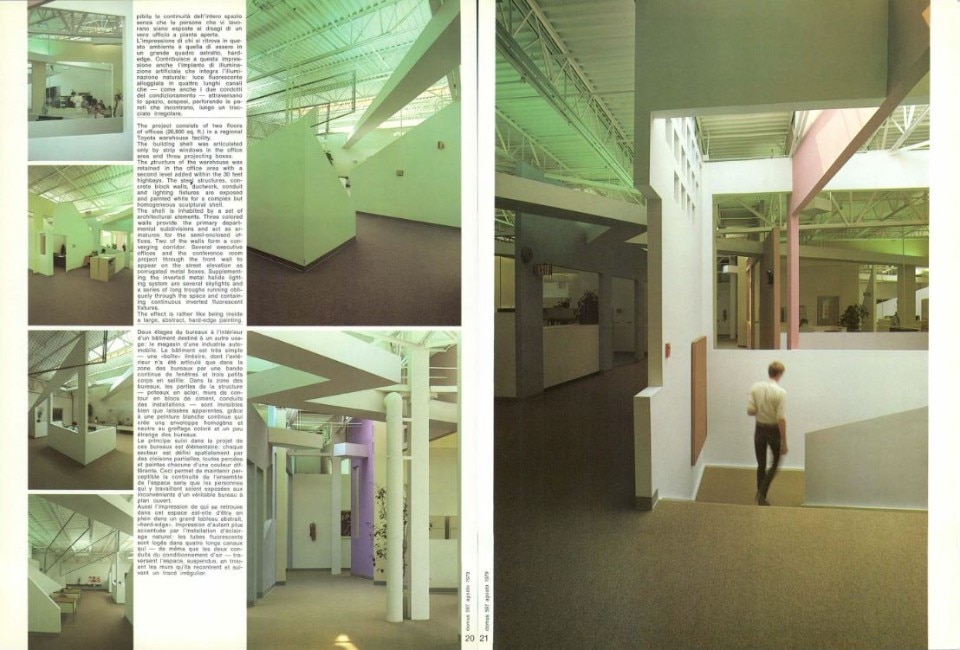

Gehry first appeared in the pages of Domus in August 1979 with the completion of the Mid-Atlantic Toyota headquarters, a building based on the concept of “open offices in a closed space”.

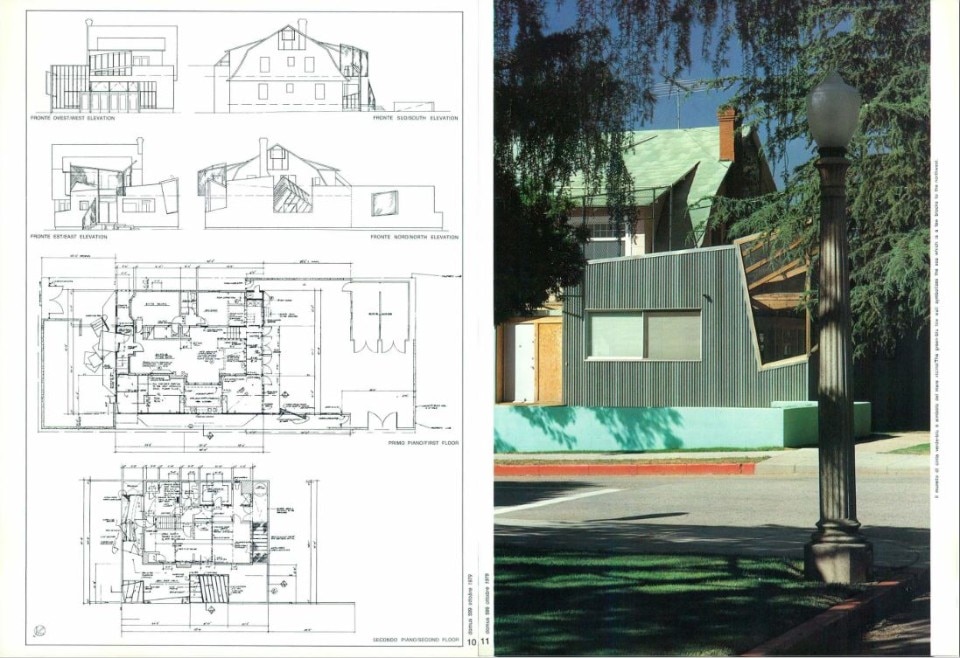

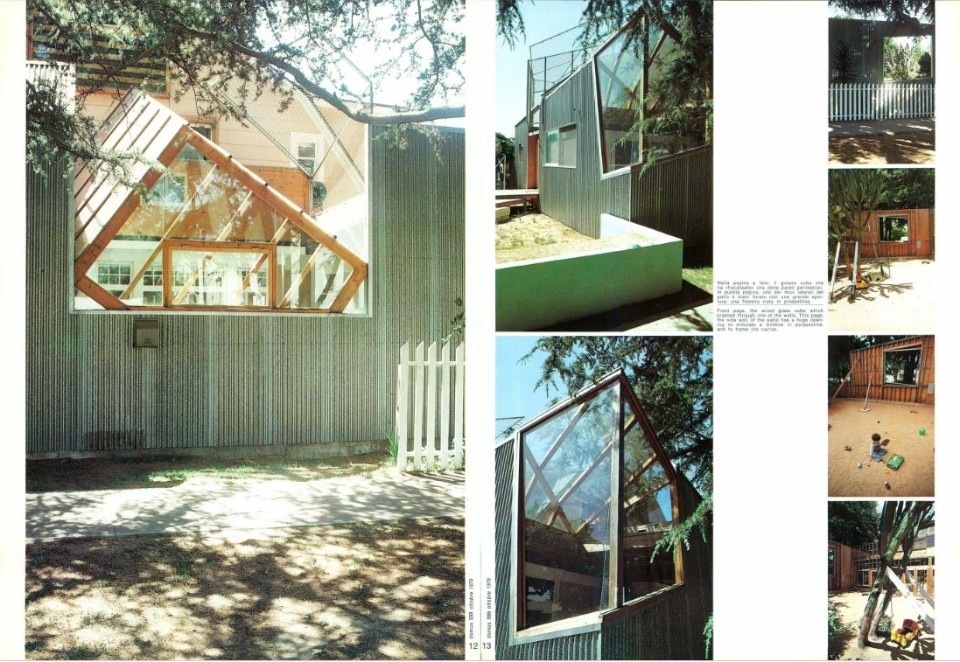

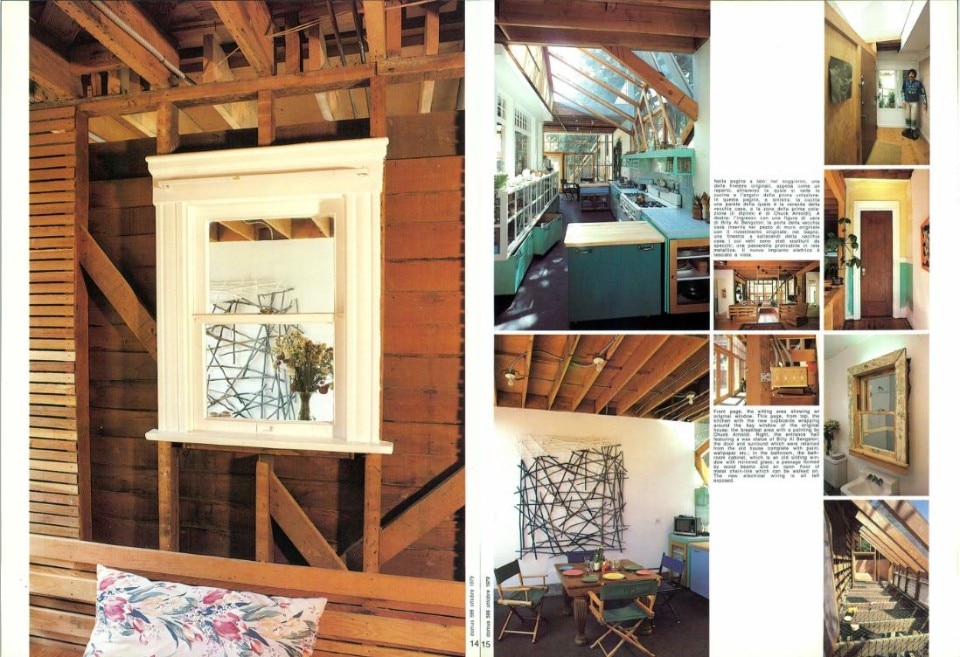

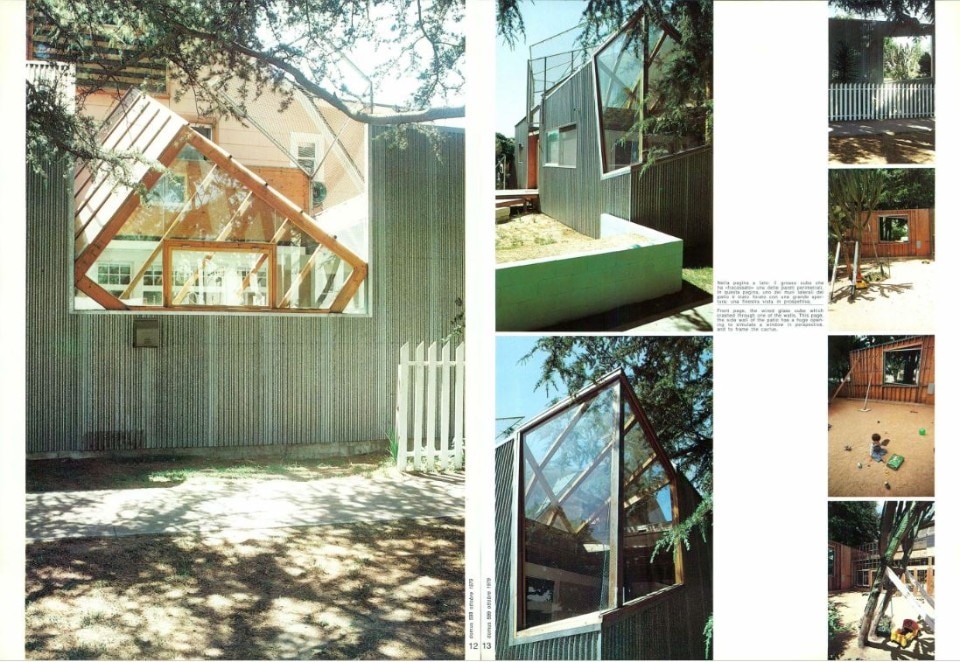

The dismantling of conventional typological schemes, a characteristic that accompanies much of Gehry's work, also appears two months later in his house in Santa Monica. It is a building that still seems under construction, an assemblage of elements clinging to a pre-existing structure, creating an image that clashes with the cliché of suburban villas.

Gehry’s house leaves no question about the identity of its occupant. His dreams and obsessions are reflected in its architecture. It is shocking because it reveals so much about the artist, and demands so much of our attention

Barbara Goldstein in Domus 599, October 1979

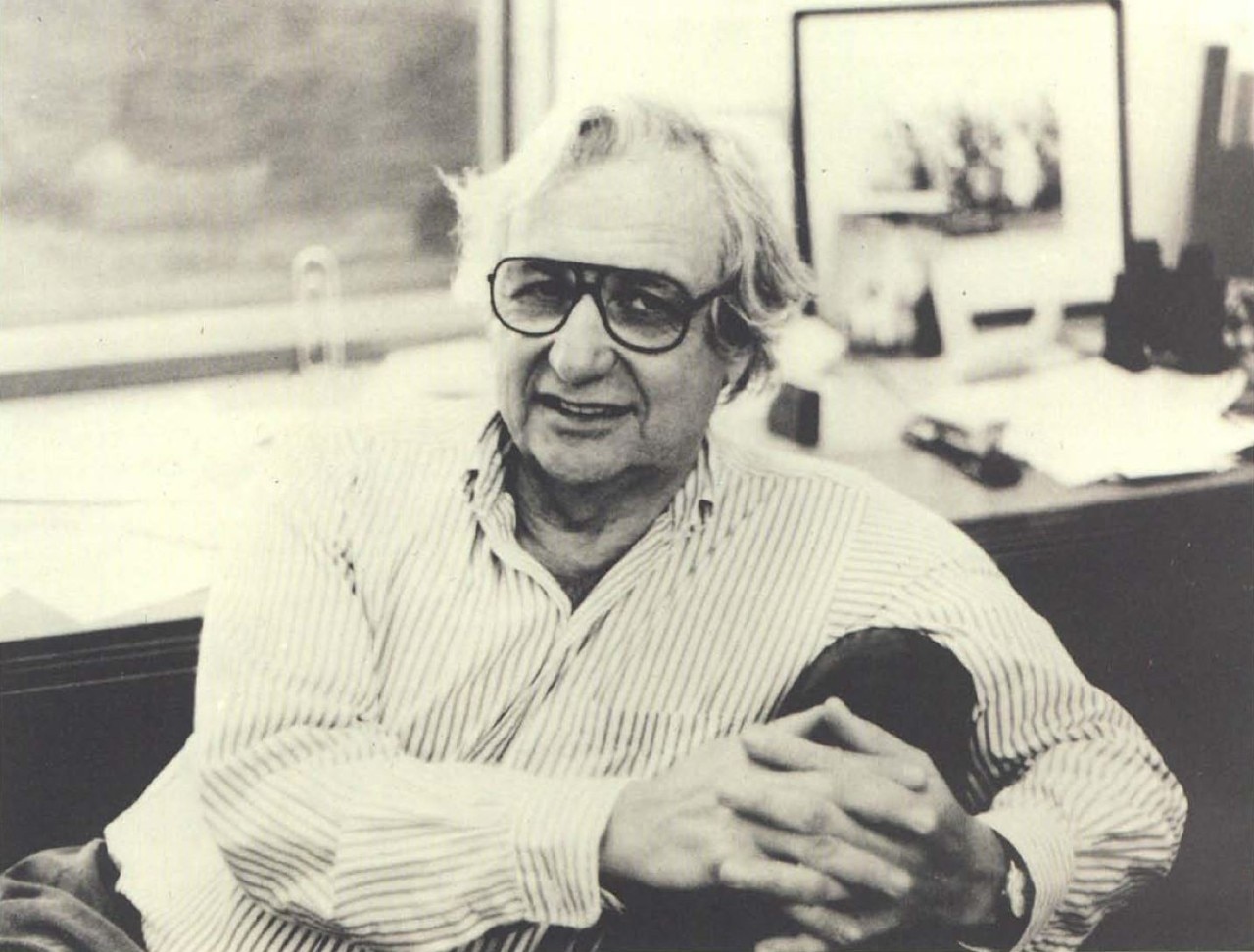

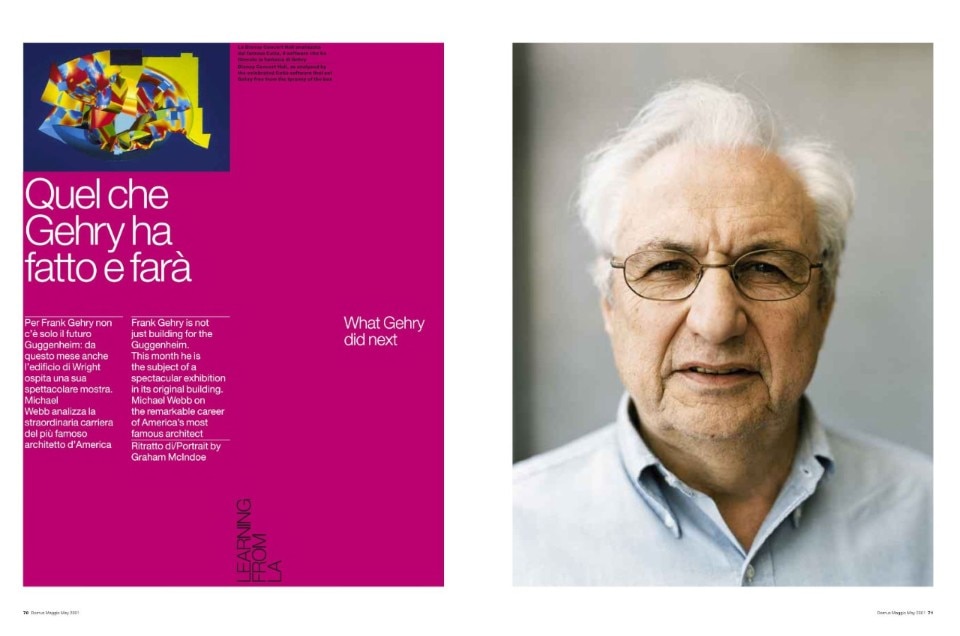

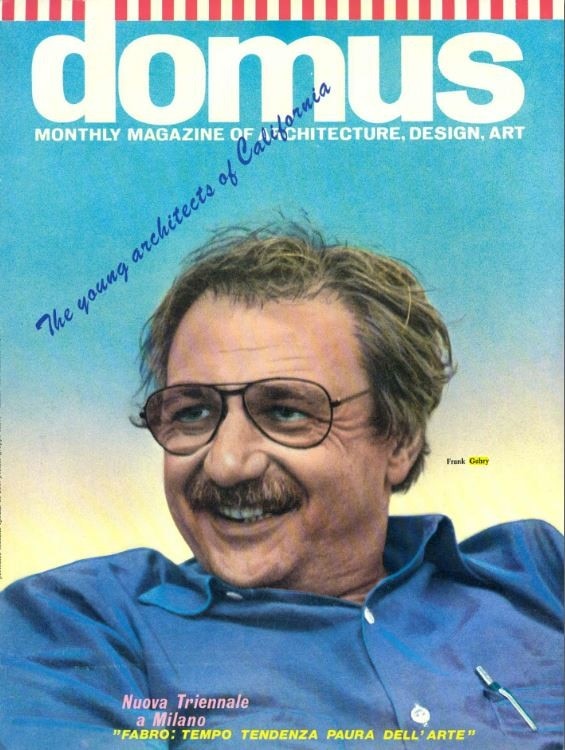

However, Gehry's grand entrance occurs in 1980 when he is portrayed in Donatella Brun's photograph on the cover of Domus 604 and introduced as a keystone for understanding Californian architecture. In the memorable words of Alessandro Mendini that follow, we read: "Everyone of us is a little Palladio producing a little, classical and closed Rotonda, conceived as a noble form isolated in a sea of refuse. You on the other hand work in reverse. In a sense, you conceive and fabricate architectural floatsam and jetsam a priori. Every house of yours, which I find beautiful, increasingly resembles a garbage bin stuffed with bits of architecture and of city."

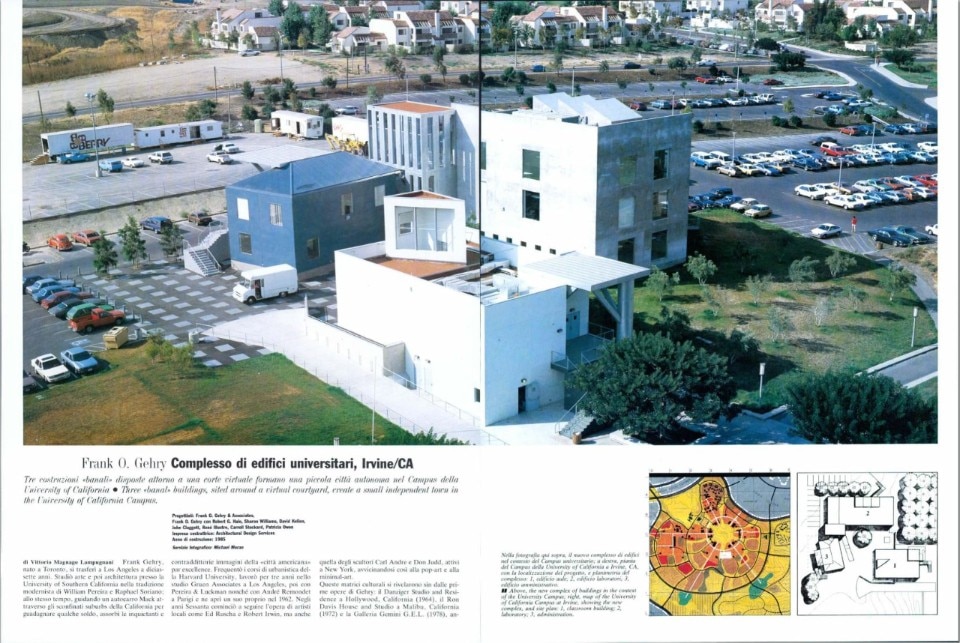

In the decade that follows, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani narrates the university complex in Irvine, California (Domus 679, January 1987). However, the 1980s also mark Gehry's first solo exhibitions and his participation in the Venice Biennales of 1980 and 1985, placing him among the great interpreters of a contemporaneity that was struggling to emancipate itself from the postmodern vulgate.

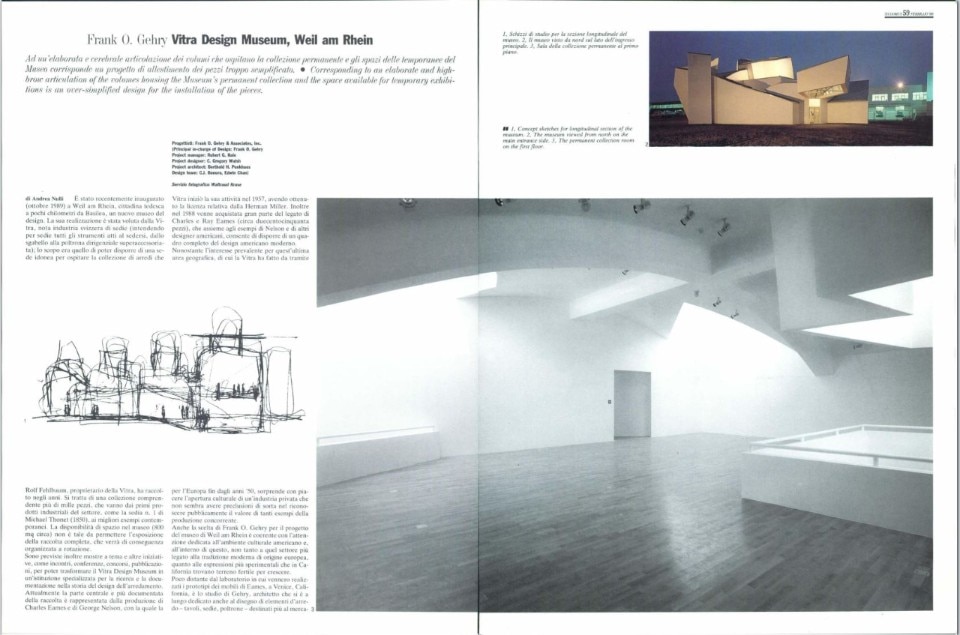

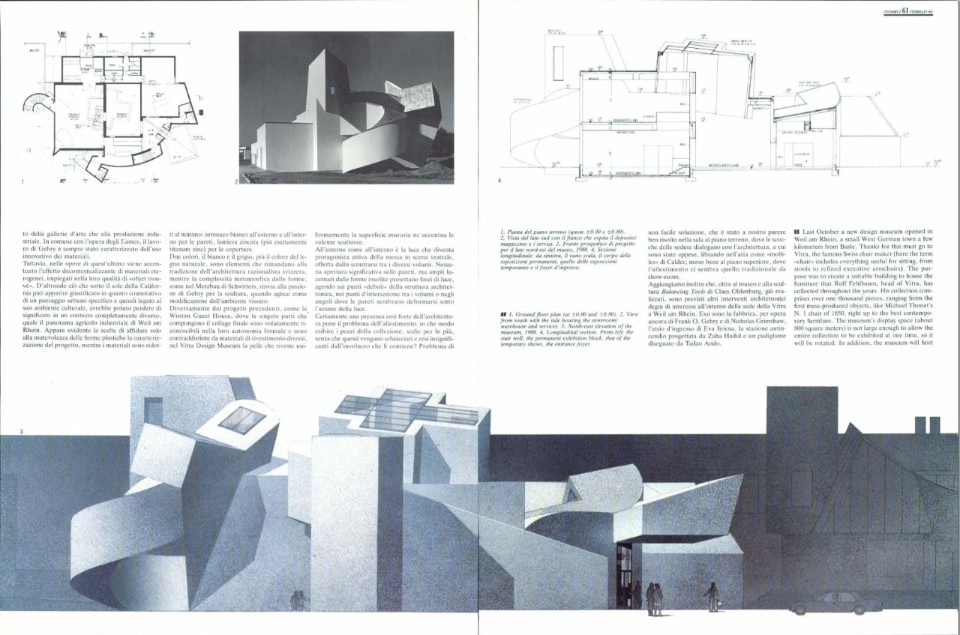

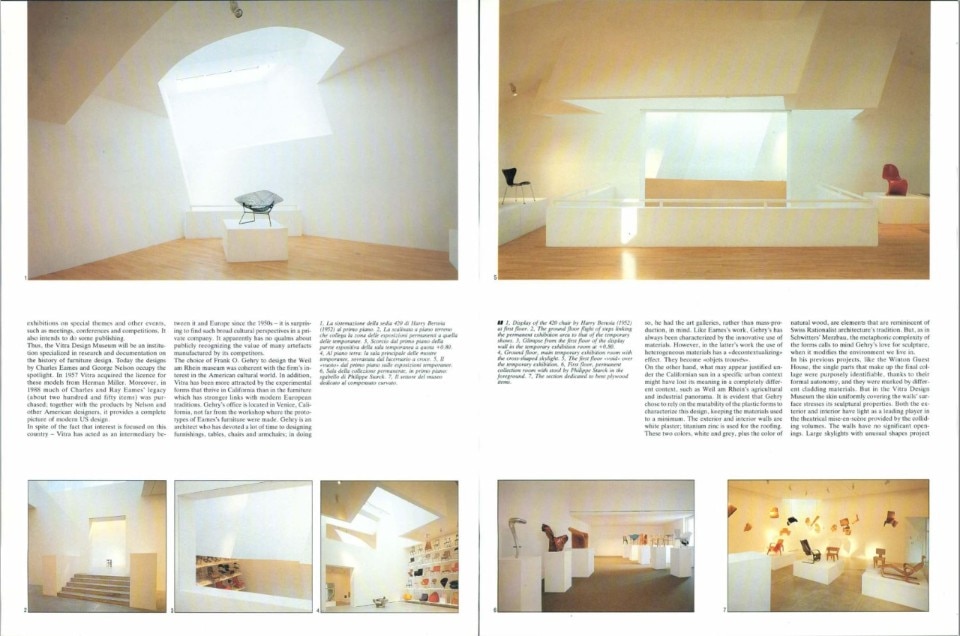

At the threshold of 1990, the first European building is inaugurated, the Vitra Design Museum (Domus 713, February 1990): a project that marks the beginning of a rapid transition to a new phase in Gehry's work from the assemblage of objects to the "freestyle." From this point forward, his architecture finds justification in the overall visual impact, in the amazement of the gesture, capturing a sense of motion and kinetic energy, and in the dualism arising between content and container in his buildings.

The relationship between art and architecture becomes a theme increasingly important not only for the projects' outcomes but especially for their genealogies and creative methodologies. The constant engagement with contemporary artists constitutes an inexhaustible source of creative stimuli with which Gehry grapples, believing that architecture can synthesize plastic sensitivity, sculptural gesture, material-formal definition, and spatial experience, all under the sign of great freedom, at times independence, from functional programs.

I always thought it was lazy, working models; I was too lazy to really visualize things in my guts so I would use a model as a crutch. I use it differently now. I design in it. I work more like a sculptor, moulding, pushing, changing and I sketch and work back to the plan

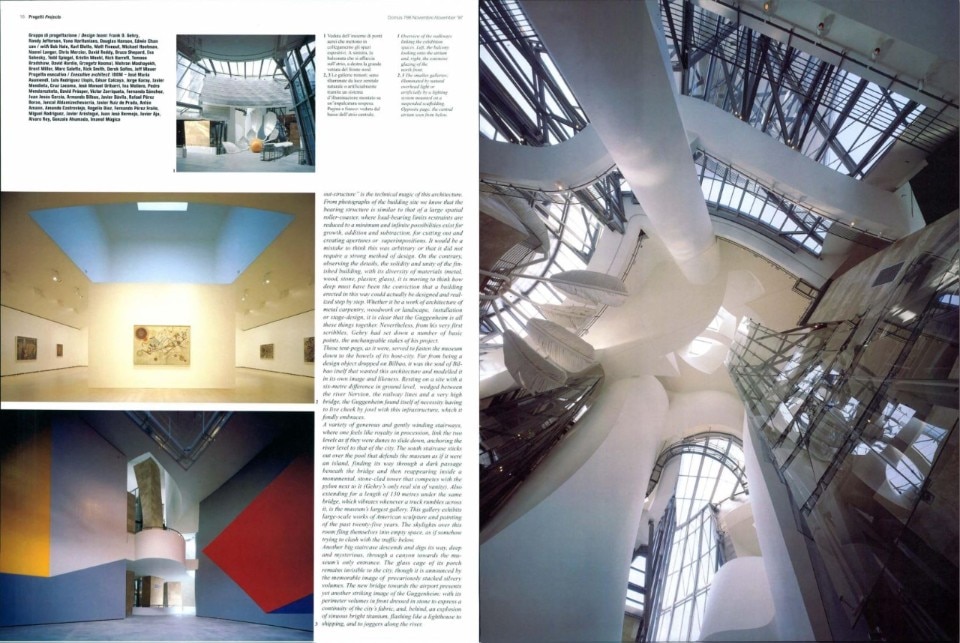

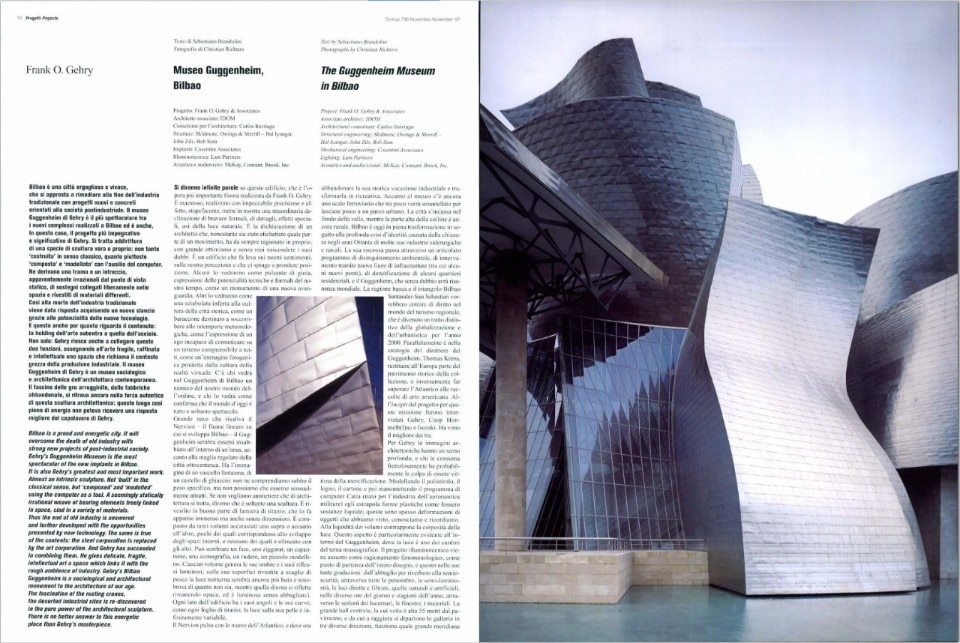

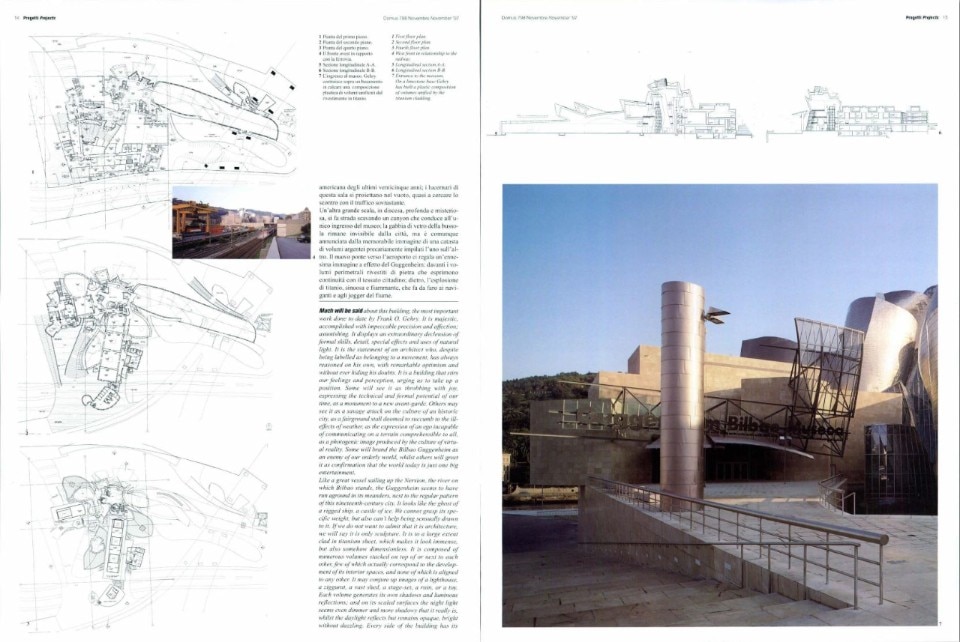

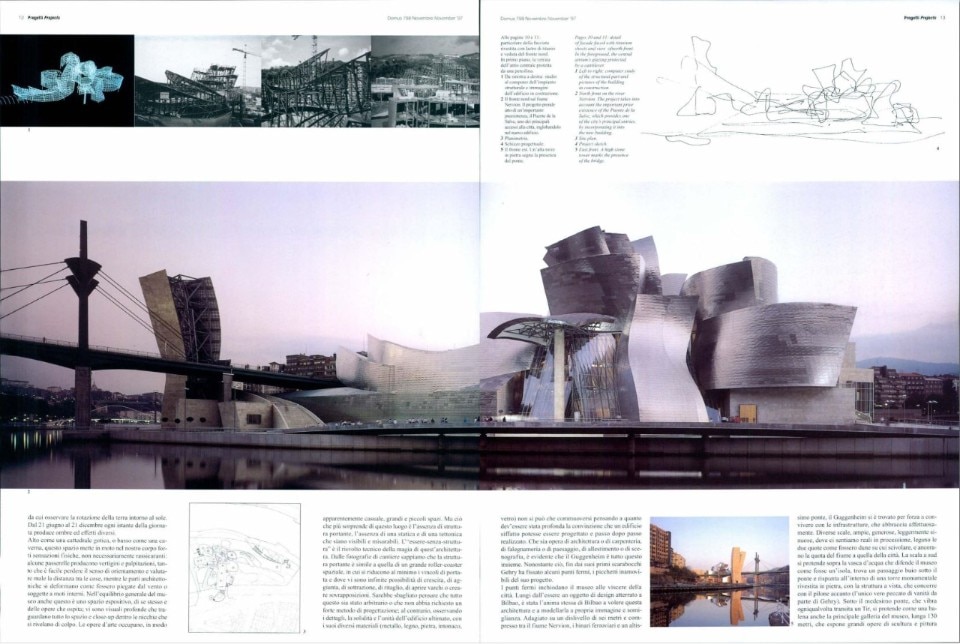

It is often said that there is a Gehry before and a Gehry after the Guggenheim in Bilbao (Domus 829, September 2000), and the same could be said for the city of Bilbao itself. The city entrusted Gehry's talent with the media relaunch of its post-industrial transformations, making it a must-visit destination on the Grand Tour of 20th-century Europe. Sebastiano Brandolini's text, accompanying the memorable images of the Guggenheim, presents it as a ghostly vessel, a castle of ice whose specific weight cannot be immediately grasped but to which one is inevitably and sensually attracted (Domus 798, November 1997).

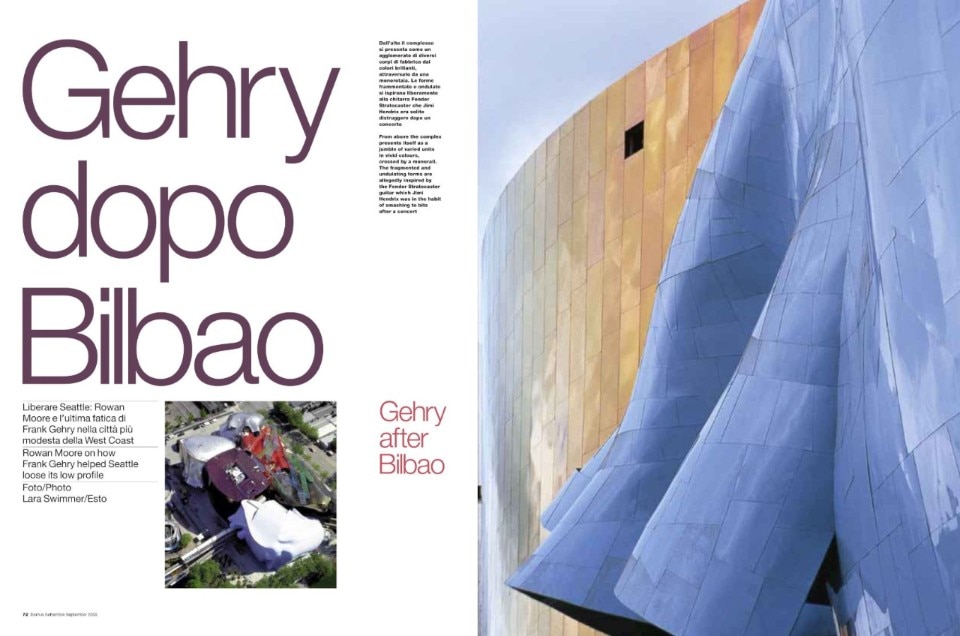

Thus, those that came after are considered epigones of Bilbao, products of media success as well as of an unmistakable style (Domus 829, September 2000) that doesn't shield Gehry from certain criticisms. While Suzan Wines speaks of a "Bilbao in New York" on the occasion of the Big Apple's Guggenheim request for an expansion project, Rowan Moore writes about a Gehry who, in the Seattle's Experience Music Project, loses the creative tension between high art, populist staging, civic pride, and serious architectural work.

Here Gehry curves more, and more audaciously, than ever before. And is as loose, as uncomposed, as unclassical as he has ever been

Rowan Moore in Domus 829, September 2000

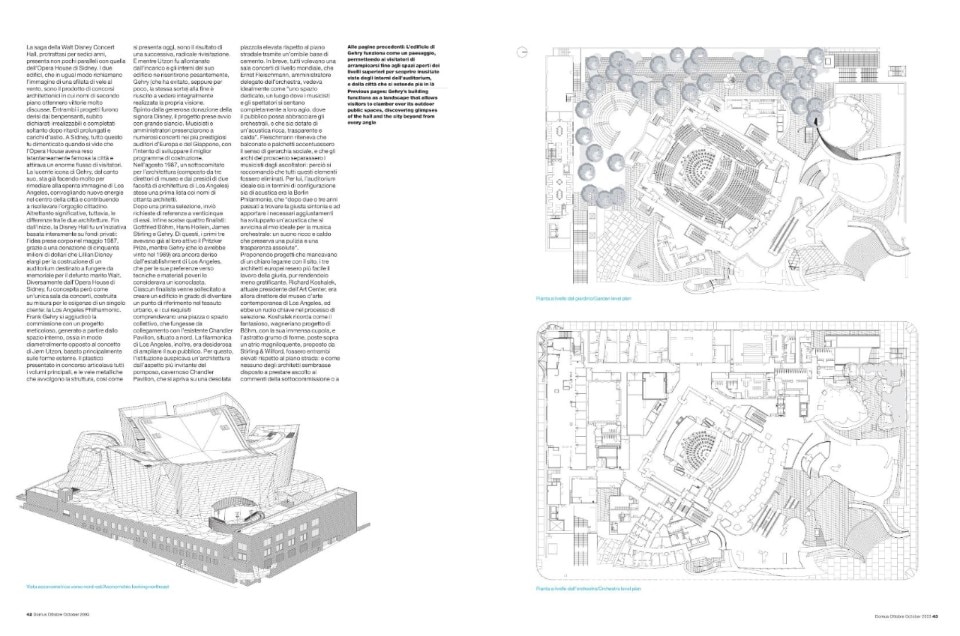

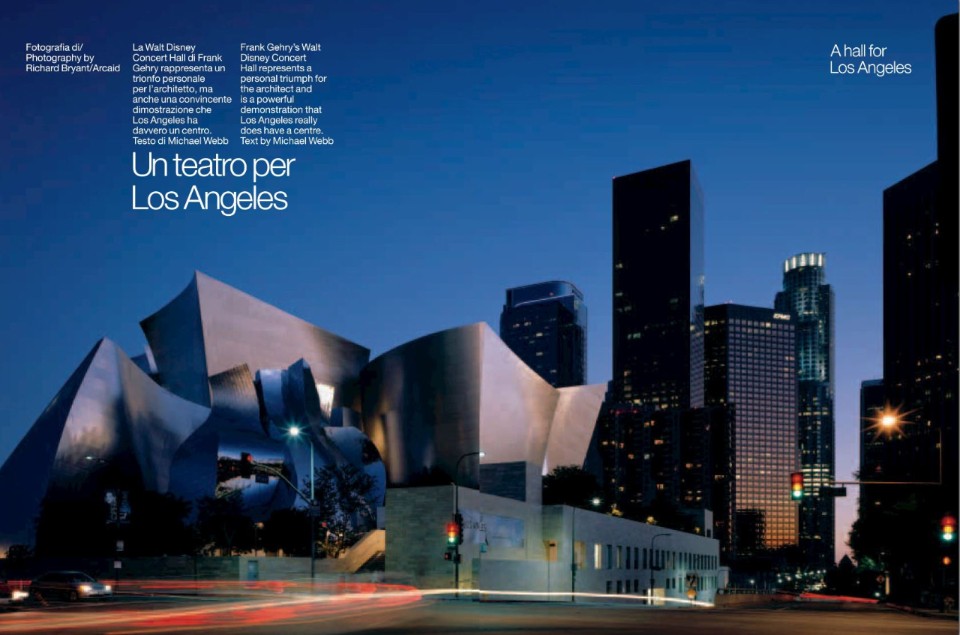

To some extent, the Guggenheim in Bilbao also has a sibling: the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is the first major architecture Frank Gehry realizes in Los Angeles. Michael Webb tells this venture in Domus 863, which began in 1987 with a $50 million donation from Lillian Disney and concluded a staggering 16 years later, with a total cost of $276 million. The article retraces the main milestones of this “saga”, which not only gave a new face to the Californian city but also definitively established one of the most characteristic features of Gehry's work.

In addition to the new urban icons coveted by clients worldwide, those would be the years when another aspect of Gehry's architecture became a branded feature. It concerned the design methodology and its narratives, evident in that indecipherable tension between the original sketch and the plastic explorations through the model.

Meanwhile, there was intense experimentation on the detonation of architectural form, on the arbitrariness and immediacy of the gesture without renouncing the quality of spaces. This could be traced in the retrospective set up at Wright's Guggenheim and narrated in Domus 837, May 2001, where the major ongoing construction sites were also featured.

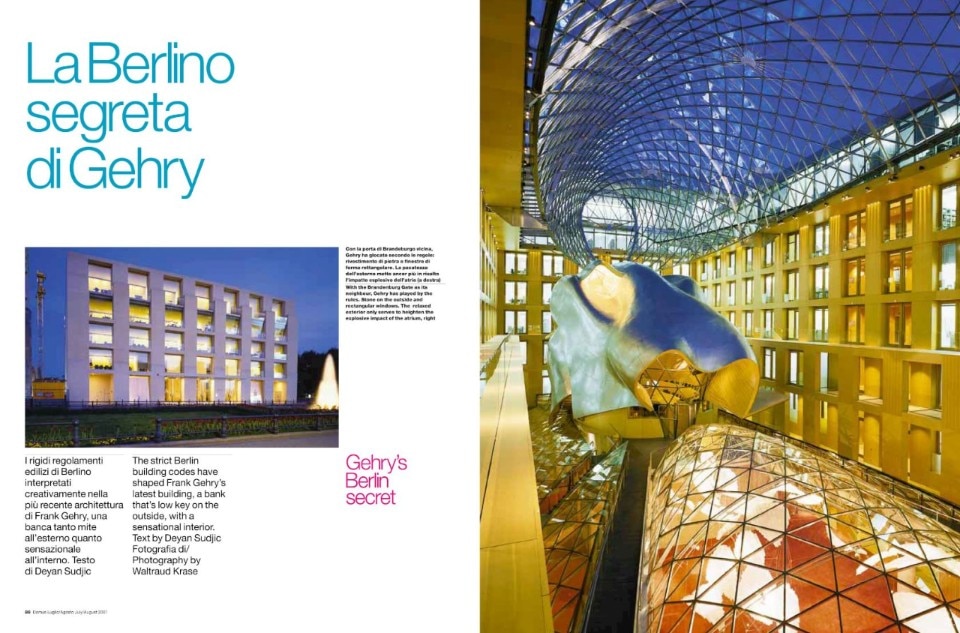

On Domus 839, Deyan Sudjic explained why the DG Bank complex on Pariser Platz was a cultural operation of extreme interest in the context of a Berlin still under reconstruction. In the shadow of the Brandenburg Gate, where urban constraints imposed by planners intersect, and in some cases clash, with the reasons of architecture, a unique example of Gehry's architecture emerged: a building that concealed within regular urban facades an unexpected internal hall where the famous conference room took center stage, shaped like a giant horse's head.

Gehry returned to Domus on issue 876, December 2004, engaging in a dialogue with conductor Pierre Boulez and journalist Paul Holdengräber on the themes connecting architecture, music, and technology. On this occasion, some references to the design culture emerge and result decisive in Gehry's work, such as the Berliner Philharmonie. Gehry was struck by the great naturalness with which Hans Scharoun guided the audience from the external spaces, then marred by the Berlin Wall, to the concert hall's interior.

The strict Berlin building codes have shaped Frank Gehry’s latest building, a bank that’s low key on the outside, with a sensational interior

Deyan Sudic in Domus 839, July 2001

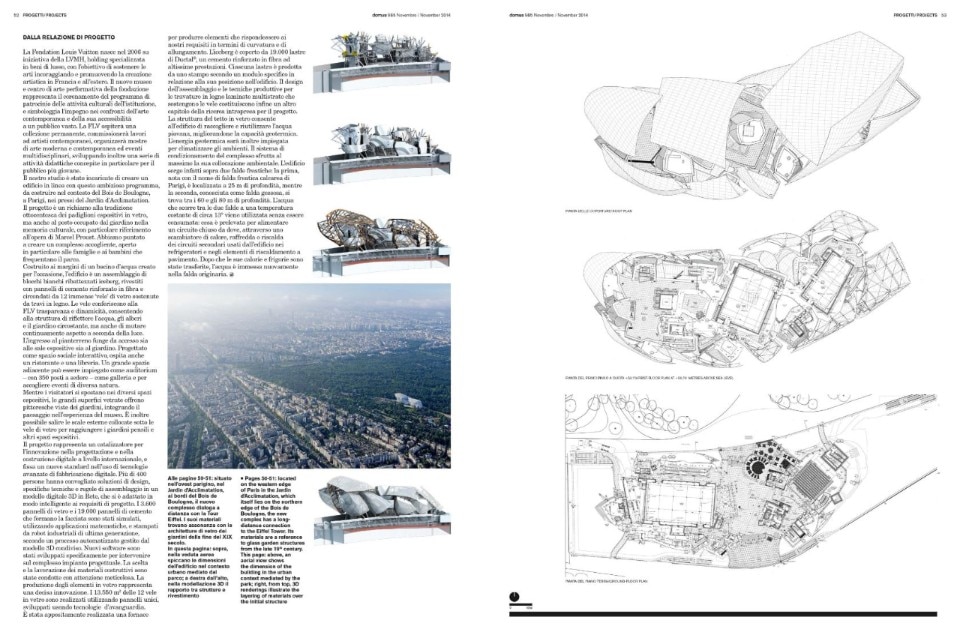

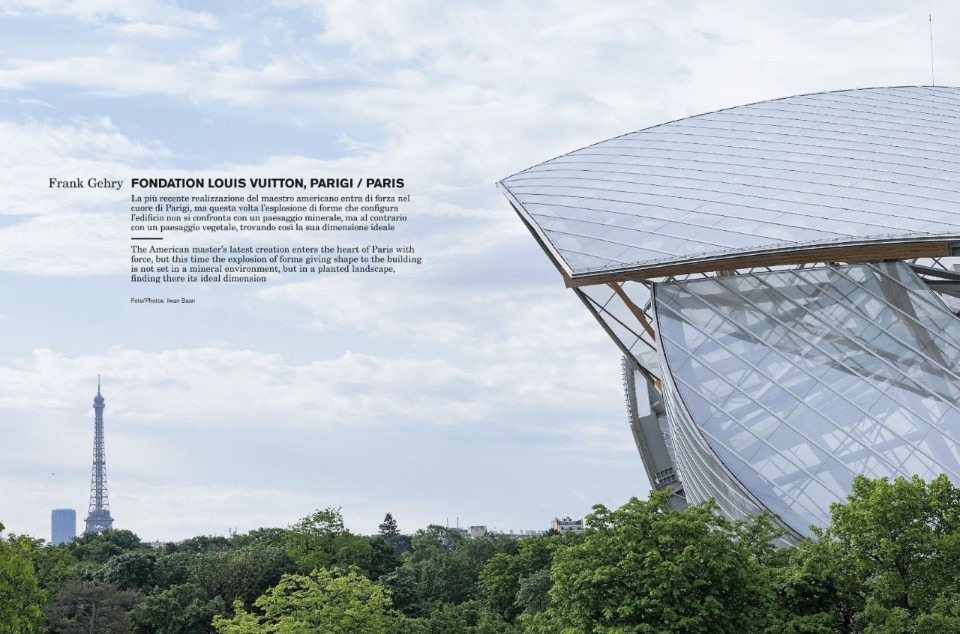

Ten years later, Paris welcomed Gehry’s latest building: the Louis Vuitton Foundation. The architecture reinterprets the aesthetic trope of the glass pavilion in the park, from Paxton’s Crystal Palace to the temporary structures of the nearby Jardin d’Acclimatation, through a strong implementation of digital technologies not only for the design of spaces but also for the production of glass and reinforced concrete panels. The large sails, already seen in titanium and steel in Bilbao and Los Angeles, are here reimagined as a device to provide shelter while maintaining a strong connection with the vegetation of the Bois de Boulogne.

Even though the Louis Vuitton Foundation is the latest architecture to which Domus has dedicated wide space, Gehry’s work has been consistently referenced in recent years, both as a historical record and in terms of its specific contribution to design culture. On issue 1022, March 2018, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani attributed Gehry the responsibility for inaugurating, with the Guggenheim in Bilbao, the phenomenon of spectacle in contemporary urban development. Two months earlier, as part of critical cataloguing of his archive, Jean-Louis Cohen reexamined the first Los Angeles house for graphic designer Lou Danziger (1964-1965), where the latent threads of the sociocultural intersections that have constantly nourished the work of Frank O' Gehry could already be glimpsed.