“I suppose we have only one idea in our lives”: these are the words with which Frank Gehry commented in 1984 on his project of twenty years earlier, his first house(-studio) in Los Angeles, built for graphic designer Lou Danziger. He was referring to the recurring practice of connecting, joining together different pieces, which indeed we also find under the dynamic shells of many of his legendary projects, such as the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, or the more recent Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. To understand the iconization process of Gehry’s own figure as a pillar of deconstructivism, however, the origin of such myth must be traced, rooted in a cultural context made of references, inspirations, but above all intersections between different historical and personal trajectories.

Jean-Louis Cohen, the French architectural historian who made these intersections the core of his research, was accomplishing exactly this operation by investigating the story of Gehry’s first Los Angeles house: somehow an outcropping of the larger project he had been working on in recent years, on the Canadian architect’s archival materials, being published in an eight-volume Catalogue raisonné. The Danziger House came out, along with an in-depth domusweb feature devoted to its drawings, on Domus issue 1020 in January 2018.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

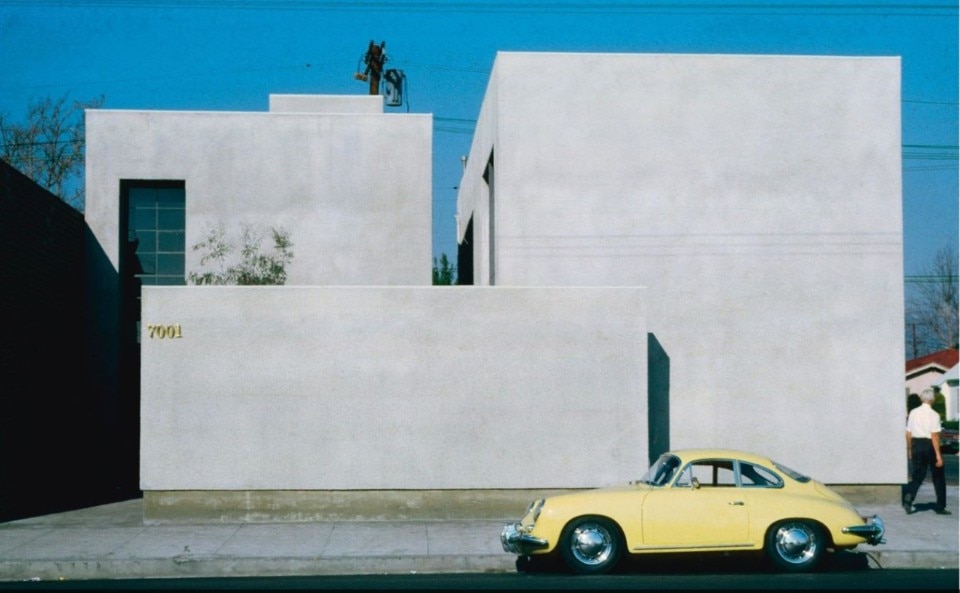

Frank Gehry, Danziger Studio and Residence, Los Angeles, 1964-1965

In his book Los Angeles. The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Reyner Banham expressed in 1971 his view of Gehry’s Danziger studio, considering: “what is important and striking is the way in which this elegantly simple envelope not only reaffirms the continuing validity of the stucco box as Angeleno architecture, but does so in a manner that can stand up to international scrutiny. The cycle initiated by Schindler comes round again with deft authority.”1 Banham was probably thinking here of Schindler’s Pueblo Ribera, built by the Viennese émigré in 1924 in La Jolla, or his Bethlehem Baptist Church of 1944 in the Los Angeles neighbourhood of Central-Alameda.

The building that triggered this first index of Gehry’s international recognition also played a decisive role in consolidating his presence on the Los Angeles stage. The successful graphic designer Lou Danziger, whose innovative designs were popular in the museum world as well as in advertising, knew of Gehry’s work as he was on the board of the Faith Plating Company, for which he had designed a new building in 1963-1964. Together with his wife Dorothy, Danziger had initially commissioned his colleague and friend Frederick A. Usher, a “very charismatic guy”, with whom Gehry had worked at Victor Gruen’s office, according to Greg Walsh, Gehry partner of many years.2 Usher asked him to take over the design.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Lou Danziger claimed credit in retrospect for the initial concept: “I sat down and worked out a floor plan and made a little wooden model of my project, essentially the basic concept with the two offset cubes. I brought the model to Frank and said, ‘Frank, can we do this for $30,000 in three months?’ Frank looked at it and said yes. Those were the days! I had given him the basic scheme, but then he did wonderful things with it.”3 But Gehry recalls: “So I met with Louis and Greg Walsh was with me and we worked on a studio. He wanted to live there and then have a studio. He was going to hire an assistant – he was expanding his office. He wanted a library.”4

The idea that he would never have to paint the building was important.

Frank O. Gehry

On a busy corner of Melrose Avenue, in a neighbourhood where printers and other businesses of the graphic trades abounded, Danziger’s idea was thus to build a 1,000-square-foot studio along with the 1,600-square-foot townhouse, contained in a single building. The first sketches reflect this unitary principle. Walsh affirms that “the big epiphany for me was when we pulled the two elements apart. For the first time we had two pieces on a single site.”5 From the beginning, the pressure of traffic in this area of Hollywood led to enclosed volumes, with a minimal number of windows opening directly onto the roads. The narrative written in 1970 by the office to support the application to an AIA Award is explicit: “The dirty, noisy and totally public nature of the surroundings necessitated completely introverting and screening the building from the street. The solution was a fortress-like structure, recessed from the street, with the residence portion sequestered behind a high wall.”6

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The early versions feature skylights with pitched roofs, generating a linguistic contrast with the main volumes which is comparable to Gehry’s Hillcrest apartment building of 1962. Then, step by step, a cubistic approach takes over, with many articulations of the programme being explored, and ultimately leading to the creation of two separate but adjacent entities, connected only at ground level. At some point, towers appear, in which the air conditioning ducts and plumbing are located. In certain cases, the volumetric assemblies recall Irving Gill’s 1915 Horatio Court West in Santa Monica, which had been published by Esther McCoy in her 1960 book Five California Architects.7 The almost endless search for convincing clusters of volumes reveals the interest Gehry already had “in the idea of connection, of putting pieces together”. In 1984, he considered this attitude as being “in a way very similar to what I am still doing, 20 years later. I suppose we have only one idea in our lives.”8 A vast number of versions were thrown on paper, and some more rendered perspectives were drawn by the gifted Carlos Diniz, who also happened to be a friend of Danziger. As built, the double scheme features a living room at the corner of Melrose and Sycamore, a studio on the west, and a garage occupying the ground floor on the east side, beneath the master bedroom.

Introversion was achieved not only with the overall enclosure of the walls, but also, according to the office, by the radical avoidance of outside-facing conventional openings, except in the kitchen, as explained in 1970: “Except for a deep slot into the kitchen, there are no windows at eye level facing the street. A clerestory skylight admits north light, preferred for design work, into the studio, while a similar clerestory in the bedroom faces east. All other windows face screened views or are located high in the wall. Street noise is eliminated through the use of sound-proofed doors and double-thickness walls with an air space.9”

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The deliberate use of solid, orthogonal volumes reveals a change of orientation in Gehry’s work, as he would later admit: “we did several studies and, I think, personally, I was very smitten with Lou Kahn at the time. I would guess that had a strong influence on me, because up to that time I was doing everything Japanese style – coming out of school.”10

While the building was under construction, I saw this crazy guy standing on the building site. It was [Ed] Moses. And then, every time I would go over there, someone else would be hanging around.

Frank O. Gehry

Walsh also affirms that both Danziger and Gehry were enamoured of concrete, in the Corbusian tradition, while Gehry would say: “I was looking at Kahn a lot, but I was also looking at Corb.”11 In a more vernacular vein, echoes of the ubiquitous “dumb boxes” of Los Angeles are easy to detect. The initial idea was to use concrete for the structure, so as to obtain a texture and colour that did not need painting and would resist wear. Gehry and Walsh were interested in the look of the underside of freeways – another Angeleno feature.12 But no public works contractor accepted to take on such a small job and, according to Walsh, “eventually, the buildings turned out to be done in wood studs and stucco, with the apparent bulk and look of concrete, in the Corbusian manner.”13

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Gehry has described the process: “Whatever was in my consciousness, I loved raw rough stucco. No buildings were being done with that. They call it ‘tunnel mix.’ It was underneath the freeways. Under the freeways they’d spray it on. So I asked the plastering contractor to do it, and they said they couldn’t; they didn’t know how. An artist friend was building a little studio in Venice. I told him what I was looking for. He said it sounded great, and if I wanted to use his garage to experiment on, he wouldn’t mind. I found out what the equipment for tunnel mix was. I went to the U-Haul and rented it, mixed the plaster, and did it myself. I sprayed it on the garage, and it was beautiful! Then I brought the contractor down, showed him the equipment, showed him the walls, and that’s how the Danziger building was made.”14

Two layers of this long-sought-after stucco were applied to a wood frame, a layer of air insuring thermal and acoustic protection. According to Walsh, “The bulk of the house was such that construction was double studs, because we wanted the walls to appear thick.”15 In some sketches, vivid coloured surfaces were envisioned, but in the end natural cement colour prevailed, as a preventive strategy against the offenses of time. Gehry indicates: “we studied various colored cements and found there was a great variety from almost olive drab to light, whitish blue-gray. We chose the latter. The idea that he would never have to paint the building was important.”16 This aspect is underlined in the building’s 1970 presentation for an AIA Award, which declares that “the surface is reasonably compatible with the dirt and grime which, predictably, did accumulate.”17

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

The studio interior, in which the darkroom forms a box, is lined with white plastered walls, with the roofing frame and ventilation ducts left visible. The visual atmosphere created by the variety of openings is carefully defined, as Gehry recalls: “I was also concerned here with trying to get natural light in and the mix of warm light and cool light for an artist’s studio. I objected to the all north-light studios, so I mixed the light at the back end and through the skylight, so it was not obtrusive, but it was mixed above eye level.”18 According to him, in the end Danziger “decided not to hire an assistant and he bought a pool table and he started becoming a billiards guy”.19

I objected to the all north-light studios, so I mixed the light at the back end and through the skylight, so it was not obtrusive, but it was mixed above eye level.

Frank O. Gehry

Acknowledged locally by Esther McCoy, the building won Gehry his first articles in the national press, and had a decisive role in connecting him to local artists, as he recalled in 1999: “While the building was under construction, I saw this crazy guy standing on the building site. It was [Ed] Moses. And then, every time I would go over there, someone else would be hanging around. Moses spread the word that this building was going up, and that it was different. That was how I met Ken Price, and Billy Al Bengston came to see it, too. I met a lot of artists around this time because they came to look at my building under construction.”20 Is it too far-fetched to see an ironic expression of this curiosity in the grey volume featured in David Hockney’s contemporary Picture of Melrose Avenue in an Ornate Gold Frame, despite the sign locating the scene 12 blocks away?

Subsequently, Gehry would take his distance from this “attempt to create a marginal, controlled world within the messiness of the LA urban environment”. He would say in 2006: “when I did it, everybody was very impressed, but I realized that neglecting a potential interface with the city was a very limiting attitude.”21 Yet, this autonomous building signed a fundamental point of inflexion in the architect’s early trajectory.

1. Reyner Banham, Los Angeles, The Architecture of the Four Ecologies, Harper and Row, New York 1971, p. 198.

2. Gregory Walsh, in Mildred Friedman, Frank Gehry: the Houses, Rizzoli, New York 2009, p. 116.

3. Lou Danziger, ibid., p. 115.

4. Frank Gehry, interview with Barbara Isenberg, Tape 14, 27 December 2005, Gehry Partners Archives.

5. Gregory Walsh, in Mildred Friedman, p. 119.

6. AIA Honor Awards Program. Descriptive Data. 1970, Gehry Partners Archives.

7. Esther McCoy, Five California Architects, Reinhold Pub. Corp, New York 1960, p. 96.

8. Frank Gehry, 1984, quoted in Francesco Dal Co and Kurt W. Forster, Frank O. Gehry: the Complete Works, Monacelli Press, New York 1998, p. 80.

9. AIA Honor Awards Program, 1970.

10. Frank Gehry, interview with Barbara Isenberg, Tape 14.

11. Gregory Walsh, in Mildred Friedman, p. 116; Frank Gehry, in Gehry Talks – Architecture + Process, edited by Mildred Friedman, Rizzoli, New York 1999, p. 46.

12. Gregory Walsh, conversation with Jean-Louis Cohen, 2 July 2015.

13. Gregory Walsh, in Mildred Friedman, p. 116.

14. Frank Gehry, in Gehry Talks, p. 46.

15. Gregory Walsh, in Mildred Friedman, p. 116.

16. Frank Gehry, in The Architecture of Frank Gehry, Walker Art Gallery, Minneapolis 1986, p. 185.

17. AIA Honor Awards Program, 1970.

18. Frank Gehry, in The Architecture of Frank Gehry, p. 185.

19. Frank Gehry, interview with Barbara Isenberg, Tape 14.

20. Frank Gehry, in Frank O. Gehry / Kurt W. Forster, Cantz, Ostfildern 1999, p. 60.

21. Frank Gehry, in Alejandro Zaera-Polo, Conversations with Frank O. Gehry, in Frank Gehry 1987-2003, El Croquis, Madrid 2006, p 16.