The International Art Biennial of Antioquia and Medellín, running from October 2 to November 25, 2025, has been reactivated after a hiatus that began in 1981.

“It had been dormant for forty-four years. Reactivating it meant taking on an enormous responsibility: bringing the name of Medellín and the department of Antioquia back onto the international cultural stage,” says Lucrecia Piedrahita Orrego, architect and curator leading the project.

It was not about celebrating the past, but about redefining what a biennial can be today.

Lucrecia Piedrahita Orrego

The suspension of the Biennial in the early 1980s can be traced to a combination of structural factors. At the time, economic instability and the escalation of drug-related violence profoundly affected urban life and the use of public space, while an institutional crisis led to a sharp contraction of cultural policies, resulting in reduced funding and a loss of long-term project continuity.

This was a context that left little room for events such as biennials—by nature complex and resource-intensive, often operating outside or at the margins of official institutional art circuits, and closely tied to processes of urban reactivation—which can only be sustained during periods of stabilization and renewal.

The aim today, Piedrahita explains, was not to revive the Biennial in a celebratory sense, but to redefine its format and its role within the contemporary urban landscape.

Architecture and unconventional spaces

Trained in architecture, museology, and art criticism, with studies in Florence and at the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Piedrahita Orrego previously served as director of the Museo de Antioquia and of an architecture and art festival that resulted in permanent interventions in public space. This interdisciplinary background is reflected in the Biennial’s framework, conceived from the outset as a city-wide project oriented toward site-specific interventions shaped by architecture and the natural characteristics of each location.

A biennial makes an artist’s thinking visible, and that always implies a relationship with architecture and context.

Lucrecia Piedrahita Orrego

“It didn’t make sense to return to a Biennial as it was conceived forty years ago. The point was not to celebrate the past, but to understand what a biennial can be today in a city like Medellín.”

“It was clear to me that it could not be a closed, self-contained event, but rather a project capable of traversing the city and its territory. A biennial is the place where an artist’s thinking is made visible, and this implies a different relationship with scale, architecture, and context.”

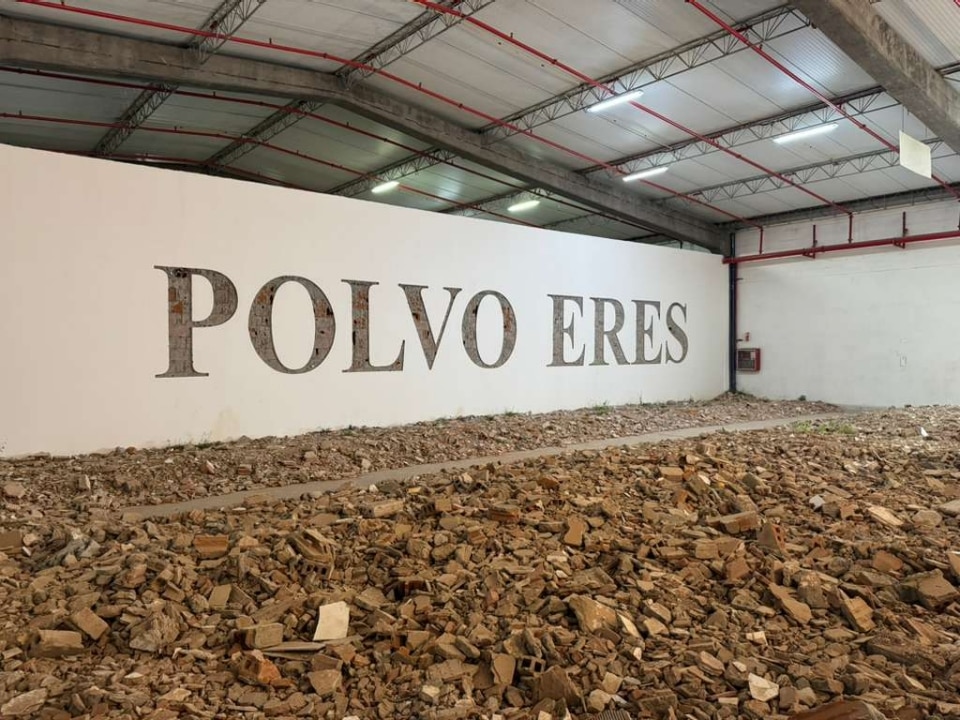

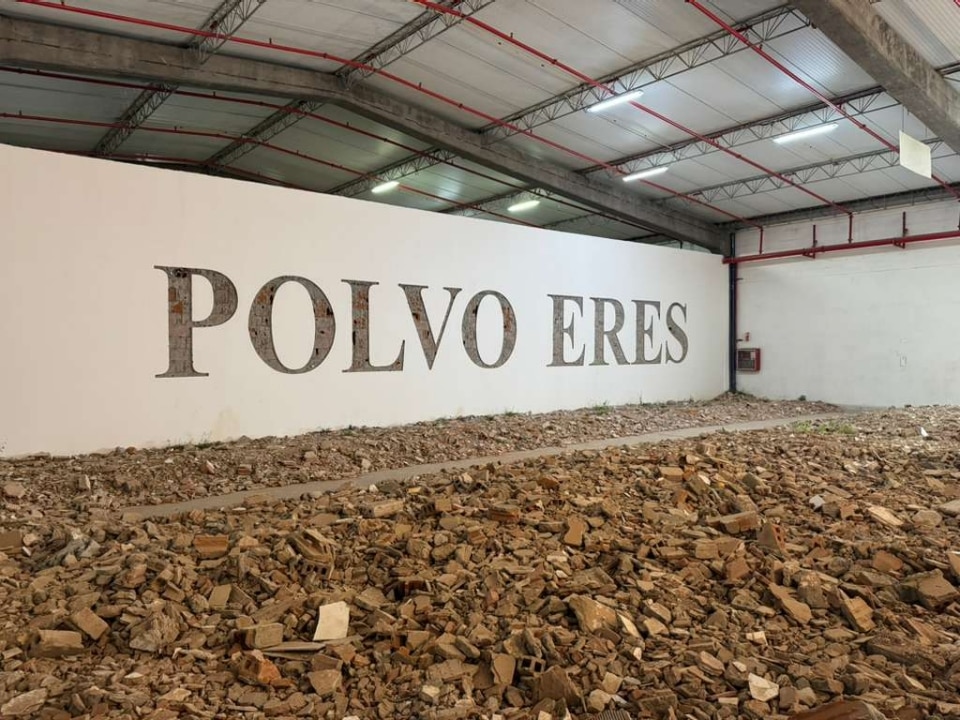

Alongside the Museo de Antioquia, which hosted the exhibition’s historical strand, the contemporary sections of the Biennial unfolded across a series of unconventional spaces selected for their urban and symbolic density. These included a railway station closed for more than forty years and a large industrial building of approximately 18,000 square meters—known locally as the former Philip Morris headquarters—unused for years and currently awaiting future redevelopment.

Upon arriving on site, abandonment had already radically transformed these spaces.

“The station had been closed for forty years, and in all that time nature had taken over the architecture. Trees had entered the pavilions, crossed the thresholds, occupied the spaces—completely transforming the character and identity of the place.”

This condition, however, was not corrected or neutralized.

“We were immediately fascinated, together with the artists. We agreed from the outset that we would not clean up the space in any way.”

“The relationship between architecture and nature proved to be its real strength. Many of the artists worked from that condition, confronting an architecture that was no longer only built, but also grown.”

Artists and production of works

Approximately 80 percent of the works were produced specifically for the Biennale. “I didn’t want ready-made works. Each artist had to develop a specific project, conceived for this context.”

The first invitation, she explains, went to Ibrahim Mahama, whose practice is distinguished by its close engagement with local communities. “He asked to arrive early, to get to know Medellín and the small villages around it. We hosted him in 2024. The result is an installation that reflects on education and development in our country.”

Alongside Mahama, Delcy Morelos was invited to develop a project rooted in ancestral knowledge and the relationship between art and land. “With Delcy, we began working on an architectural pavilion that brought together artistic knowledge and peasant knowledge. It was important for the Biennale to include this kind of knowledge, so deeply rooted in our region.”

Another emblematic intervention is by Makoto Azuma, who created a large-scale installation on the façade of a Baroque church in a small town near Medellín. “It was an important work for the entire exhibition: it brought in people who never thought they would go to see a contemporary art exhibition.”

Medellín was literally dressed by the Biennial.

Lucrecia Piedrahita Orrego

“For me, it was essential to follow the production process month after month—through site visits, meetings, phone calls, and video conversations with the artists.”

Alongside the central curatorial framework, a third line was devoted to what Piedrahita describes as “invisible” artists. “We encountered very young artists as well as people nearly eighty years old, living and working in the region. They may not have defined themselves as artists, but in their homes and workshops there were works that spoke directly of life.”

Mediation, accessibility, public

“Medellín was literally dressed by the Biennial.”

The city’s response was immediate and widespread, supported by a substantial effort focused on accessibility and mediation.

“The subway facilitated access by opening dedicated corridors, an efficient taxi service was made available, and the entire city was branded for the Biennial. This made it possible to reach as many local visitors as possible, in addition to tourists and professionals from the art world.”

The involvement of small municipalities around Medellín required the construction of a decentralized logistical system and extensive collaboration with local institutions—a valuable, and still relatively rare, practice for international events seeking to extend across a territory, but which too often underestimate travel times, mobility constraints, and the conditions of public access and engagement.

Universities also played a central role, particularly through cultural mediation initiatives entrusted to students trained as guides.

“We had around fifty young people who wanted to act as guides. Mediation was very important—necessary. When thinking about events like these, one must not forget that contemporary art is not always easy to understand.”

“Whenever I could, I personally led many of the visits—not only for government officials or the press. It was important to explain what lay behind the works, so that people could recognize themselves in them.”

“The greatest satisfaction—after seeing the Biennial take shape—was hearing people say, ‘We can’t wait another forty years; in 2027 the Biennial has to happen again.’ I know I won’t be the curator of the next edition, but I hope the city can count on the return of this experience every two years. The only way to build audiences and culture is through continuity.”