Paris, May 1989. Seeking shelter from a grey Parisian day, visitors at the Centre Pompidou — designed by Rogers, Piano and Franchini — found themselves face to face with a strange spectacle: hyper-realistic, brightly coloured coffins. They came from Ghana, the artistic product of one of the country’s southernmost regions. “Magiciens de la Terre,” the exhibition curated by Jean-Hubert Martin, then director of the Pompidou, introduced them to Europeans for the very first time — who, from the 1980s onwards, began to collect them.

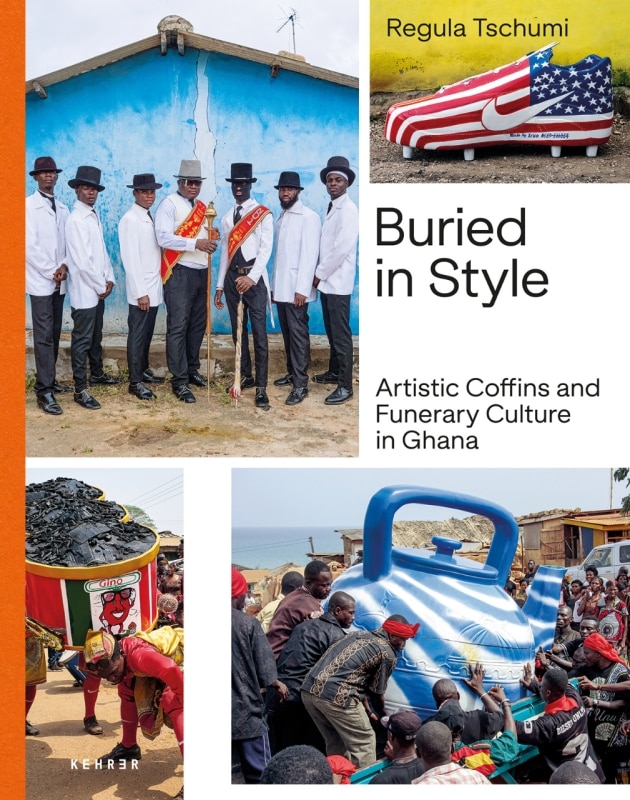

Coffins shaped like trains, fish, Coca-Cola bottles, or sneakers. Mortuary chambers decorated like dance halls, with balloons, televisions, and disco balls hanging from the ceiling. Dancers in suits and ties carrying coffins on their shoulders.

Over the past three decades, Ghanaian funerals have become a global phenomenon. On YouTube, vloggers visit coffin workshops; on Instagram, the choreographies of Benjamin Aidoo — the dancing pallbearer — go viral, while tourists increasingly ask to attend ceremonies that remain deeply private for the families involved.

Yet beyond the attraction for kitsch and camp aesthetics, these coffins tell a far deeper story — one about Ghana’s colonial past, the impact of Christianization, social transformation, and the extractive gaze of global tourism on poorer regions. Buried in Style. Artistic Coffins and Funerary Culture in Ghana (Kehrer Verlag, 2025) gathers twenty years of research by Regula Tschumi, the foremost scholar of Ghanaian funerary traditions. Domus spoke with her to understand what the global fame of these rites has truly meant for those who live them.

The secret coffins of the Ga nobility

Between 1874 and 1957, during British colonial rule, large traditional funerals were discouraged or even banned — especially those reserved for tribal chiefs and kings. In southeastern Ghana, around Accra and along the coast, these rituals began to be held in secret, often at night.

It was the Ga ethnic group — from whom this entire tradition originates — who developed a symbolic solution: coffins identical to the ceremonial palanquins used by nobles while alive.

“While the palanquin was kept in the palace and they did secretly a copy and they buried the copy by night,” says Tschumi. Austere and unadorned, these early coffins bore family emblems or symbols of power — eagles, lions — and looked very different from the figurative coffins we know today. Yet they were, in essence, their ancestors.

From ceremonial palanquins to Coca-Cola bottles

Tschumi first discovered these objects while still at university, after seeing them depicted in paintings by a Ataa Oko, “the pioneer” of the coffin art, according to Tschumi, who used to draw his former palanquins. She began field research in 2002, but for years no one seemed to know anything about their history.

“At first, I thought they were simply palanquins,” she says, “but when I asked about them, people told me they hadn’t been used for centuries, that they had all been destroyed. In truth, ordinary people never came close to those night funerals — they were afraid.”

It was a story constructed by journalists and Europeans. And it ended up in the history books.

Regula Tschumi

It was the Christians, Tschumi later discovered, who changed the rules and expanded the practice beyond the noble elite. They were the first to commission personalized coffins for common people. “They started to make coffins in the shape of bottles, of shoes, of symbols that represent the profession or represent a dream of the deceased person... All these things are very basic, not connected with religious beliefs, not connected with totems and all these things.”

From the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, these practices gradually spread across the Accra region. Workshops opened, and a new generation of craftsmen emerged. In the 1980s, when Jean-Hubert Martin visited Ghana, he encountered these coffin makers through missionaries and collectors — and commissioned works from two of them, Paa Joe and Kane Kwei, for European exhibitions.

Kane Kwei and the Western myth of African art

The first show to feature Ghanaian coffins was held in a small Los Angeles gallery. “Magiciens de la Terre” came next — more famous, but also less accurate. “They named them works of Kane Kwei, while they were not works of Kane Kwei — only about half of them came from his studio. The rest came from Paa Joe,” explains Tschumi. And so a misunderstanding took root: Kane Kwei became, for the Western world, the “inventor” of the Ghanaian coffin tradition — even though it had existed for decades before him. “It was all a story created by journalists, by Europeans,” says Tschumi. “And it is now in the history books.”

Today, the largest collection of Ghanaian coffins is found not in Accra, but in Basel, at the Museum der Kulturen. Collecting them privately is difficult — they require space, context, and careful preservation. The coffins that travel from museum to museum are often the same ones, built specifically for exhibition purposes. The funeral rite itself forbids — and indeed condemns — any reuse of coffins. Even Tschumi, who has witnessed countless funerals, owns only a few.

Death as a risky, pop business

In Ghana, death has always held central social and spiritual importance, but in recent years it has also become a business tied to extractive tourism. “It’s now common to pay to attend a funeral, and every amount is carefully recorded in the family’s accounts,” explains Regula Tschumi. Families go into debt to ensure their loved ones receive a “proper” burial, while new economies thrive on the growing visibility of funerary rites. “Funerals compete to attract visitors and donations — if they’re not lively enough, people might simply not give money.”

This logic turns layered rituals into increasingly performative spectacles. The variety of funeral customs — which differ greatly across Ghana’s religious communities — is flattened into a single, marketable image. Tourists are unaware, for instance, of the country’s military funerals, where gunfire is part of the music and fatal accidents are not uncommon, or of the quieter, traditional rites closer to indigenous religious practices.

Meanwhile, they pay high fees to watch Aidoo’s pallbearers repeat the same dance they’ve already seen on Instagram. And perhaps one day, Tschumi fears, they might even pay to attend staged funerals, built entirely for their entertainment.