Fourteen point nine million dollars. An extraordinary sum that today, in the world of contemporary art, might purchase a thought—sometimes not even a brilliant one—fixed on a blank canvas, a provocative gesture preserved in formaldehyde, or, better still, an idea later sold as an object.

Through a private negotiation with Sotheby’s, Italy’s Ministry of Culture has acquired a remarkable poplar panel measuring 19.5 by 14.3 centimeters, painted on both sides by a man born in Messina around 1430, who died in the same city in February 1479 and, in between, forever changed the way the West looks at a human face: Antonello da Messina’s Ecce Homo.

Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio, as he appears in the records, is the short circuit of European painting. A Sicilian formed in Naples in Colantonio’s workshop. He learned from the Flemish without ever having seen them in person—or perhaps he did; the debate is still open, and art historians have argued over it for a century. He later went to Venice, where he taught Giovanni Bellini that light is not drawn, it is breathed. In a life of roughly forty-nine years and fewer than forty surviving works, the master from Messina absorbed the analytical precision of the Flemish school—the ability to render every pore of the skin, every reflection in the eye, every vein in the wood. He then grafted it onto the rational construction of Italian space.

The result is not a sum. It is a mutation in painting. Before him, the North and South of Europe spoke two different languages. After him, they confronted the same pictorial grammar. The Ecce Homo acquired by the Italian state is likely the last Antonello still in private hands, formerly in the collection of a Chilean collector and later passing through Wildenstein & Co. in New York and the Florentine dealer Fabrizio Moretti.

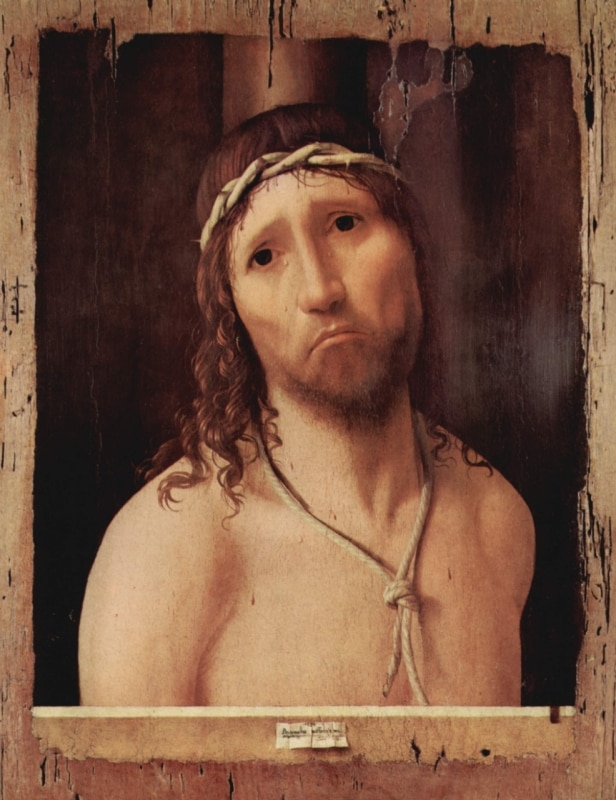

Let us turn to the work itself. A small double-sided panel, datable to around 1460–65, which is essentially two works in one. On the recto, Christ of the Ecce Homo emerges from the darkness behind a stone parapet: eyes reddened and swollen, rivulets of blood running from the crown of thorns down his forehead and chest. This is not an idealized Christ. Not an icon. He is a young, vulnerable, wounded man who looks directly at us. On the verso, a penitent Saint Jerome kneels in a rocky, desert landscape before an open book and an inkwell—the translator of the Bible caught in his most intimate gesture.

Before him, the North and South of Europe spoke two different languages. After him, they confronted the same pictorial grammar.

The double image and the small scale suggest what Federico Zeri had already intuited when he brought the panel to public attention in 1981: this is an object of private devotion. Something its owner carried with him, probably in a leather satchel, repeatedly kissed, rubbed, touched. The image of Saint Jerome on the back still bears the marks of that wear. It is not damage but a trace of a faith worn smooth through touch, through the repetition of a sacred gesture. If design is the relationship between form and function, then this panel is the design of prayer.

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of the acquisition is that this Ecce Homo is not an isolated case in Antonello’s production. It is the beginning of an obsession. The master from Messina returned to the suffering face of Christ at least six times in his short lifetime. Each version represents a different chapter in the same investigation—one that is not only pictorial but philosophical: how far can pain be represented? How far can it be embodied?

Here, the panel, datable to the early 1460s, is the point of departure. Here Antonello is still young, still immersed in the Neapolitan and Flemish tradition. Christ has something raw about him, almost unsettling in his immediacy. In 1985 Zeri compared the grimace of the face to that of a mafioso—a remark that, behind its absurdity, contained a precise intuition: Antonello did not paint ideal types. He painted real men. Faces seen on the street, transfigured by painting into something absolute.

The chronologically subsequent version is the one now in the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola in Genoa, from around 1470, where Christ’s bust appears modelled by a more sophisticated raking light, and the expression becomes more melancholic than pathetic, as if pain had found its own composure, its own inner measure. The work bears the signature Antonellus Messaneus me pinxit.

With the Christ Crowned with Thorns in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, datable to around 1470, Antonello’s research reaches an advanced stage. The bust, slightly turned, stands out in space with a new monumentality and fullness. The stone parapet, already present in the newly acquired panel, here becomes a mature compositional device: it separates Christ from the viewer and at the same time projects him toward us, creating a short circuit between distance and proximity that is one of the most modern features of Antonello’s language.

If design is the relationship between form and function, then this panel is the design of prayer.

The Ecce Homo at the Collegio Alberoni in Piacenza, dated 1473, is perhaps the best known and most studied version. Christ is bound to the column of the flagellation, frontal, the crown of thorns pressing and tearing at the skin. The dark background is devoid of detail, and all attention converges on the face, on the contracted brows, on the downturned lips. An icon that retains elements of the Byzantine tradition of the Man of Sorrows yet fills with a carnality and physical presence that belong to the Renaissance.

A fourth version, dated 1474 and once held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna until the Second World War, is unfortunately lost following Nazi looting. Only photographic documentation remains. The Genoese version at Palazzo Spinola, datable to around 1474–75, shares the same compositional structure as the Piacenza example but introduces subtle variations, as if Antonello were attempting to refine not so much the image as the feeling the image must evoke.

To these we can add the Christ at the Column in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, datable to 1476–78, which closes the series on a more intimate, inward note—the fatigue of suffering, one might say.

Taken together, these six versions tell a story that goes beyond art history itself. They speak of an attempt of one man to capture in an image the essence of another human experience: innocent suffering. Each version is a different answer to the same impossible question. And each answer shifts, ever so slightly, the boundary of what painting can do.

The newly acquired work is the zero moment. The first formulation of an idea that would accompany Antonello throughout his life. It is the most instinctive, the roughest, the closest to direct experience and, for that very reason, perhaps the most powerful. It does not yet have the composure of the Metropolitan nor the monumental symmetry of Piacenza. It has something rarer: urgency.

What remains to be decided is its museum destination. Wherever it goes, what matters is that after centuries of silence in private collections it returns to what Antonello conceived it to be: an object to be contemplated.

Ecce Homo. Behold the man. Here we are.

Opening image: Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, recto, c. 1470. Courtesy Sotheby's