The architecture of Tbilisi—თბილისი in the local alphabet—can only be described as composite. What is now the capital of Georgia was founded in the 5th century by Vakhtang I Gorgasali of Iberia, but in some neighbourhoods archaeologists have uncovered traces of human settlements dating back to the Early Bronze Age and even the Paleolithic. Much like Rome, Damascus or Athens, stratification is the key to reading Tbilisi.

Because of its strategic position, in the heart of the Caucasus, at the crossroads between East and West and along a central node of the Silk Road, Tbilisi has been the object of continuous conquests since its foundation. From the Persians to the Ottoman Empire, from the Mongols to Tsarist Russia and then the Soviet Union, each dominion has left behind an architectural imprint that still blends today with local traditions. Modern times are no exception, and the buildings planned, constructed, or demolished in Tbilisi are often part of political positioning strategies and the subject of intense public debate.

This is the case with the Rike Park Auditorium by Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas, at the centre of the city’s latest controversy. Commissioned in 2010 to the Italian studio by then president Mikheil Saakashvili, the auditorium—wedged between an artificial park along the river and the old town—was part of a broader programme intended to put Tbilisi on the map of international architecture, at a moment when the entire country was beginning to turn more decisively toward the West.

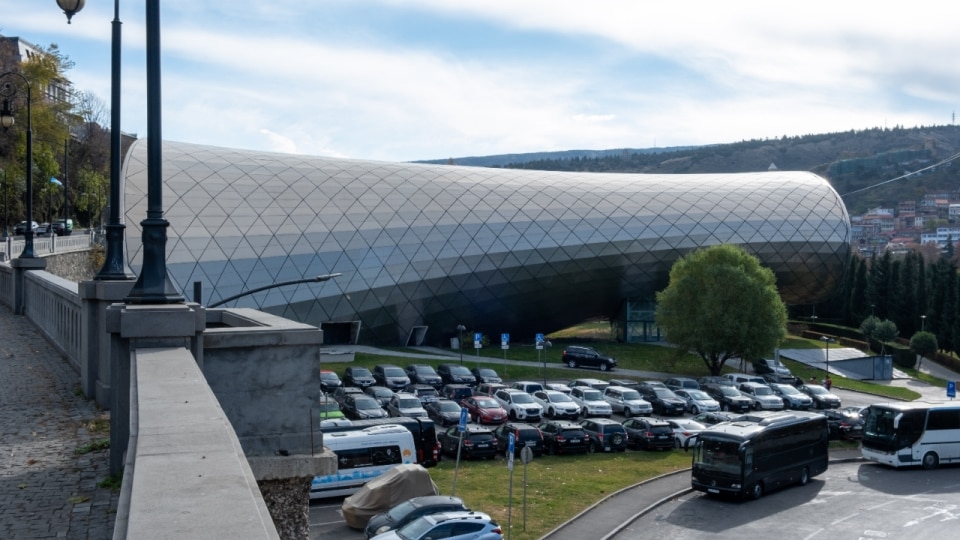

In reality, as Nino Tchatchkhiani, founder of the Tbilisi Architecture Archive, explains, “the building formally reprises ideas from the proposal Fuksas presented for the competition for the Hermitage Museum in Vilnius,” and it was not truly designed to be site-specific. The project occupies a 10,000-square-metre site and consists of two soft, differently shaped elements in reinforced concrete and steel, clad in steel and glass panels, connected as a single body by the retaining wall against which they rest. Costing 40 million euros, it was meant to accommodate 550 seats, but the interior was never completed and the auditorium has always remained empty and closed. Despite retaining a controversial kind of beauty, today it lies in the park next to a car park, like a large metal carcass. It nevertheless remains the symbol of a Georgia that, especially after the 2003 revolution, had begun to dream of a path toward European integration.

The city does not belong to them, and the battleground for their personal conflicts should not be the city’s parks and buildings.

Nino Tchatchkhiani

In 2025 the building returned to the centre of public debate: first in January, after the tragic death of a teenager who fell into a pit on the abandoned site, and then again in May, when mayor Kakha Kaladze expressed his intention to demolish the auditorium, describing it as “dysfunctional” and “disorderly,” and not in line with the city’s urban development objectives. Kaladze, a member of the ruling Georgian Dream party founded by oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, stressed the need for a new project of similar size that would be both functional and aesthetically appropriate for the area, likely a hotel. To date, however, the municipality has provided neither a timeline for demolition nor more precise details about the future project. The only certainty is that, after a series of failed attempts, the site was purchased at auction in 2020 by businessman Davit Khidasheli, becoming part of the broader trend of privatisation that is leading many to invest—and speculate—in the Caucasian capital.

Often according to fire-sale rather than fair-sale logic: “After thirteen years of inactivity, the building, constructed at a cost of more than 90 million GEL [the local currency, about 30 million euros], was finally sold by the state for just 10 million, after being repeatedly put up for auction,” Tchatchkhiani explains. “It subsequently changed hands once again and ended up becoming the object of financial speculation. The cost of completing the interiors is estimated at around 20 million GEL, a sum that no investor seems willing to spend. The cost of dismantling and disposing of it in a landfill, on the other hand, has probably never been calculated, but it is likely no lower.”

“The Fuksas concert hall is not the only project to have suffered a similar fate,” Tchatchkhiani comments. “I believe this attitude represents the highest degree of irresponsibility. Regardless of what one may think of its architecture, regardless of the emotions it may evoke, the Georgian state does not have the financial resources to simply forgo hundreds of millions of GEL spent on construction under one government simply because the subsequent government seeks to erase every trace of its predecessor, both its successes and its mistakes.”

At this point, it becomes necessary to question the possible future of this immense, never-completed project, whose destiny remains uncertain: “Would it be wiser to relocate the building to another site? Would it not be more honest to ask professionals—and the general public—for ideas on how to resolve this situation? However, if the state itself has been unable to initiate such a dialogue, would a private owner, whose sole objective is profit, dare to launch a broad public debate? And what does Massimiliano Fuksas think of this project today?” The architect’s opinion, like the future of his work, also remains uncertain. After an initial moment of openness, he told Domus that he was no longer available to comment.

“Nothing positive will happen,” Tchatchkhiani concludes, “until the governments of Georgia—whoever they may be—understand that the city does not belong to them, and that the battleground for their personal conflicts should not be the city’s parks and buildings.”

Opening image: Courtesy Adobe Stock