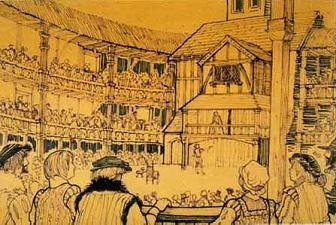

London, January 30, 1595. The air around The Theatre vibrates with a dense, almost solid electricity. The crowd presses in. Bodies collide in anticipation. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men raise the curtain, and for the first time, the world witnesses what will become the most famous tragedy of Western culture: Romeo and Juliet.

William Shakespeare draws from Arthur Brooke’s narrative. He absorbs its structure, then injects it with an urgency that would forever alter our emotional grammar.

At that moment, Elizabethan theater stood as the last stronghold of an anthropological space. It was not a container for passive spectators, but an identitarian and relational environment, saturated with history, taking form as it was spoken. Far from passive, the audience became part of the very architecture of meaning. Aware that “all the world is a stage,” they recognized themselves in that Verona reconstructed in the mud of London.

This tension between bodily reality and mythic abstraction is the ground on which art has tried, for centuries, to negotiate a truce. Painters became the new playwrights. They attempted to reclaim that carnality, oscillating between the rigor of chronicle and the surrender to passion.

Art, ultimately, has stopped at the threshold of that kiss.

In 1823, Francesco Hayez confronts the theme with The Last Kiss of Romeo and Juliet. Not a simple farewell, but a civic urgency of Romanticism erupting on canvas. Look closely at Romeo’s feet. Destiny is decided there. One is already on the ladder, projected toward escape, exile, emptiness. The other remains anchored to the floor, to life, to her. It is an aesthetic of tension.

You can almost hear Juliet’s tremor: “Wilt thou be gone? It is not yet near day. It was the nightingale, and not the lark, that pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear.” There is a chaste yet burning sensuality in the way her hands rest on his shoulders. An eroticism of the threshold. The kiss is not static, but a breath stolen from the sentence of time.

A few decades later, in 1870, the perspective shifted radically. Ford Madox Brown strips away theatrical rhetoric, revealing a sensuality that is almost tangible. There is no heroic pose here, but the weight of bodies. Romeo’s arm wraps around Juliet’s waist in a grip that is both protection and desire, an embrace that seems to resist the inevitable.

In Brown’s work, dawn light is not a bucolic blessing, but a threat: “Look, love, what envious streaks do lace the severing clouds in yonder east.” Light exposes her pale skin, creating a powerful erotic contrast with the heavy, dark velvet of the garments. Realism becomes feeling.

In 1884, Frank Dicksee drew us into a dim, suspended atmosphere. Sensuality turns languid, almost oppressive, mixing the scent of flowers with the residual warmth of bodies on the balcony. Juliet appears abandoned, nearly overcome by passion, in a surrender of the senses that anticipates decadent aesthetics. In this half-light, the farewell becomes final: “Farewell, farewell! One kiss, and I’ll descend.”

Beauty translates into romantic sweetness. Light becomes an accomplice, concealing Juliet’s profile while exalting the embrace about to close in a kiss, before night gives way to that “glooming peace” destined to envelop Verona.

But the balcony is only the antechamber of silence. Art, ultimately, has stopped at the threshold of that kiss.

Fate, however, grants no reprieve. The tragedy is fulfilled in the paradox of a poison that unites and a blade that liberates. In the darkness of the tomb, Romeo delivers his final farewell to beauty: “Eyes, look your last! Arms, take your last embrace!”

Exactly 431 years ago, The Theatre fell silent before a revelation. The power of those lovers did not lie in longevity, but in a burning urgency capable of defeating eternity.

The curtain falls. The lights go out. Yet that cry against the injustice of fate continues to resonate through layers of pigment and the lines of in-quarto pages. Because, despite the centuries, “never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo.” And yet, never was a story more necessary to remind us what it means to be, after all, terribly human.