A major obstacle for Rome has always been its uniqueness, its epic quality. Paradoxically, the very factor drawing crowds of visitors eager to discover its history, whether through a Jubilee, the Roman Forum, or even a condensed version staged in a metro station.

“Caput mundi”, and Rome is immediately removed from the global debate on cities. “Eternal City”, and it is instantly denied the right to belong to the present.

“But, you know, it’s Rome”. A statement of uniqueness that would deserve at least some unpacking, as the capital does have a present, no matter how complex: a metro system perpetually under construction, vehicular traffic that is hard to control, then schools, public green spaces, employment opportunities, housing pressure.

It is within this context that the transition to 2026 has brought an almost surprising development: not one but two exhibitions, both in Rome, explicitly engaging with these issues, attempting to give them form and to channel them to a broad audience, thereby positioning the city within a present shaped by global urgencies. Each is linked, in its own way, to the Venice Biennale; they might seem to describe two different planets, yet a second look reveals that spaces, actors, and themes are literally the same.

Caput mundi, and Rome is immediately removed from the global debate on cities. “Eternal City”, and it is instantly denied the right to belong to the present.

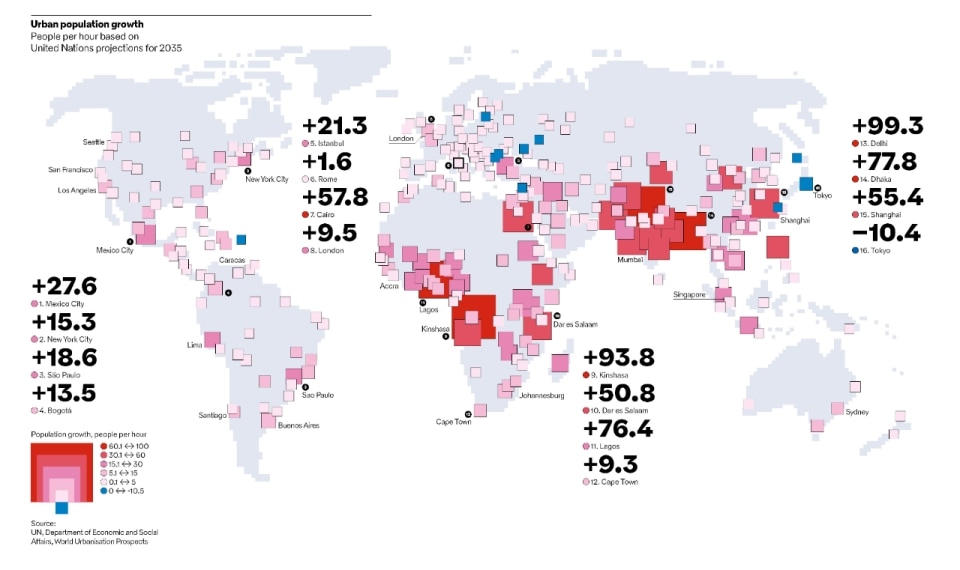

“To overturn the viewpoint that frames (Rome) as Caput Mundi and place it within a global context” is precisely what Ricky Burdett set out to do at the MAXXI with Roma nel mondo (Rome in the World), an exhibition that seeks to represent the capital as “a complex contemporary urban artefact, socially stratified, expansive, and green”. It is the aggregation, visualization, and above all comparison of data that makes this operation possible, and shareable with an audience that, in part, is also an actor within these dynamics, sometimes without realizing it.

Moving through the sequence of Zaha Hadid’s galleries, visitors are welcomed by a display that immediately recalls another Burdett-curated exhibition, Città, Architettura, Società (Cities, Architecture, Society), the Venice Biennale of 2006. The language still works twenty years on. Rome is finally compared, data in hand, with Tokyo, Hong Kong, New York, Paris, Mexico City. Diagrams, maps, photographs (by the likes of Barbieri, Jodice, Linke) tell a clear story: a municipal territory as large as a region (almost 1,300 km²), while the city of Paris (excluding the banlieue) covers less than a tenth, just 105 km². A car ownership rate that dangerously approaches one-per- inhabitant, 803 per 1.000 residents, to be compared with New York’s 249 or Tokyo’s 80.And then comes greenery: clearly punctuating the historic city – after all, Villa Borghese is roughly half the size of Hyde Park – but quickly merging into a vast, regional-scale green belt, largely productive. A capital in the middle of farmland.

Such contemporary, explorable, comparable image perhaps makes the second section of the exhibition less disruptive: the one devoted to historical, literary, and artistic imaginaries, to that very mythology mentioned at the outset – still, revisiting Martin Parr and rediscovering Freud’s reading of Rome as a psychic metaphor remains significant. Visitors are then led to a large terracotta model of the city at 1:7.500 scale, onto which data from its present are projected. Il DNA di Roma (Rome’s DNA), the title reads.

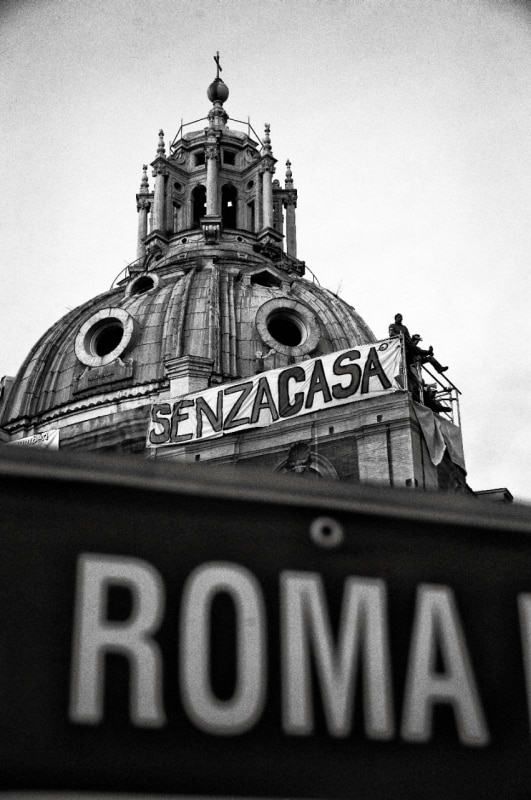

DNA is also the starting point for the other exhibition, at the MACRO, but this time it is the DNA of a struggle (Il DNA di una lotta): the struggle for housing in a capital that, since 1870, has represented a real challenge, now addressed at a 1:1 scale. Abitare le rovine del presente (Inhabiting the Ruins of the Present), curated by Giulia Fiocca and Lorenzo Romito (Stalker), originates from a project presented for the Austrian Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale. Here too, the central element is a helix, both a DNA strand and a spiral column, like Trajan’s Column, on which artist Jessi Birtwistle replaces the conquest of Dacia with a century and a half of occupations and settlement practices that have shaped the profoundly plural identity of Rome’s habitat.

The surprising nature of these two exhibitions lies in their ability to take Rome out of its own cultural box, making its present perceptible even from the outside.

The narrative begins with late nineteenth-century speculation, moves through the demolitions and forced relocations to peripheral housing estates during the Fascist era, then the explosive postwar urbanization, between INA-Casa projects and shantytowns that struggled to disappear until the 1970s, when space was made not so much for solving the problem as for transforming it.

One of the exhibition rooms is organized around a wooden installation – a scale model of Corviale – and a large map, which together narrate those “ruins of the present”: areas or buildings left behind by a time in motion, where the creativity of urban populations has given rise to experiments that, over the years, have consolidated into vital parts of the city itself.

There are stories of interspecies habitation, such as the former Mercati Generali, redesigned and masterplanned multiple times since 2002 but never transformed, now renaturalized; and the lacustrine ecosystem that has formed around the waters of the Lago Bullicante. There are transformations that are now fundamental to Rome’s response to a nearly chronic housing crisis, such as Spin Time, the occupation of the former INPDAP headquarters in Esquilino area, now divided between residential use and cultural service spaces for the city. What emerges is a snapshot of a present-future which is far from being any tension-free, once again situating Rome within a dynamic unfolding at global level: the risk of evictions and clearances in Italy has become extremely high, already materializing in Milan and Turin; beyond the national context, even in different forms, the exclusionary action of the neoliberal city toward less privileged segments of the urban population persists.

The surprising nature of these two exhibitions lies in their ability to take Rome out of its own cultural box, making its present perceptible even from the outside, despite adopting curatorial and exhibition languages that appear to come from opposite galaxies – and from clearly identifiable periods: early-2000s data visualization on one hand, and the situationist, “informal” activism of late-millennium bottom-up practices on the other.

These languages too, like the content they convey, are Rome. They are its history, and they allow that history to be placed in a forward-looking perspective rather than one overly fixed on the past, beyond Forums and Trajan’s Columns.