“Countryside: A Place to Live, Not to Leave”, the new exhibition from AMO, the research arm of OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) marks the second iteration of a research project first introduced at the Guggenheim Museum in New York with “Countryside: The Future” in 2020, and is presented across two sites: the Qatar Preparatory School and the National Museum of Qatar. Much like its first chapter, the central assertion remains unchanged: that we shall reconsider peripheries resisting urbanization as crucibles for future living.

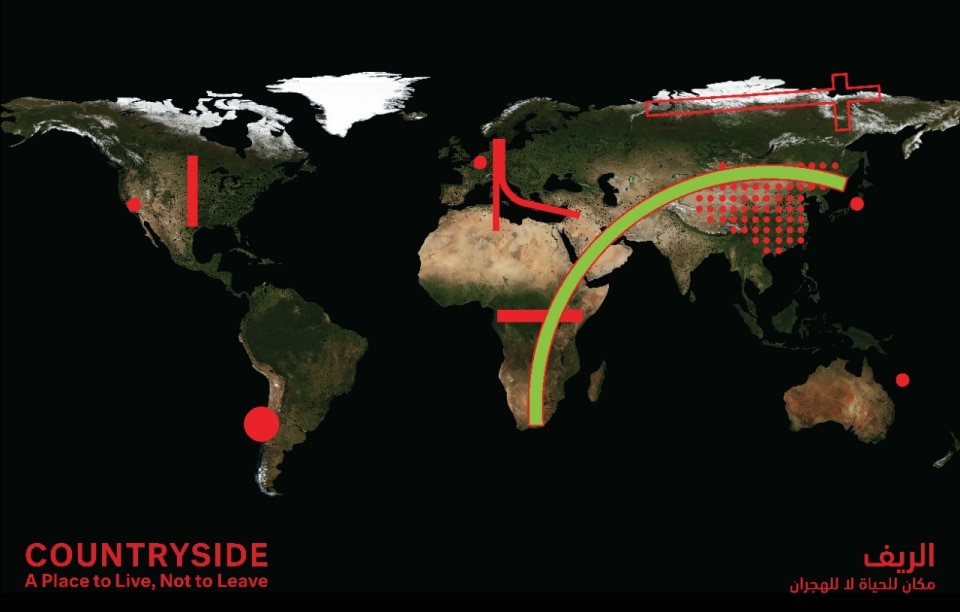

This new chapter asks us to consider “the Arc”, a made-up, landlocked, and coastfree stretch of land sprawling from South Africa through East Africa, traversing Qatar and Central Asia, and curving into Eastern China, forming the basis for new research conducted by AMO together with dozens of international researchers and collaborators.

The exhibition resists the all-too-familiar narrative of crisis and instead sketches a fragile optimism: that the countryside might offer new prototypes for sustainable, fulfilling life.

“The Arc” is not simply geographic in scope. It is simultaneously approached as a demographic fault line and a combination of disparate places across the three continents. It’s where 85% of the world’s population lives today, destined by 2100 to be the locus of humanity’s densest concentrations.

In places like Qatar, at the fulcrum of this transformation, “the Arc” is both crossroads and laboratory: a terrain replete with legacies of colonial disruption and the seeds of radical possibility. “Qatar is the optimal setting for this exhibition and one of few places nowadays in which there is an effort to tackle issues of extreme climate, water stress and food security through technology, education, diplomacy and culture,” says Yotam Ben Hur, “Countryside” project leader and architect with AMO.

The exhibition, in its dual setting, is as much process as product. At the National Museum of Qatar, visitors are immersed in the themes that animate “the Arc”: modernization’s tug-of-war with tradition, the ecological imperatives of new agricultural and energetic practices, and the digital rewiring of rural economies. But it is at the Qatar Preparatory School where the project’s real ambition unfolds. Here, classrooms become studios and testbeds, where teachers and students, joined by invited collaborators, convene in workshops and collective experiments. The grounds themselves, activated through test fields of date palms, vegetables, and flowers, demonstrate the transformation of desert soil through hydroponics, advanced irrigation, and greenhouses—a living archive of adaptation and invention. A dense series of public programs over the coming 12 months include workshops, guest lectures and symposiums devoted to conservation, desert farming, technology, politics, arts and culture.

It is through the new innovative microcosms that are put forward—coding schools in barns, electric tractors plowing new furrows, and the tension between the smartphone’s connective promise and the preservation of ancestral rhythms—that the potential of the “countryside’s” true character emerges. The exhibition resists the all-too-familiar narrative of crisis and instead sketches a fragile optimism: that the countryside, far from being emptied by the gravitational pull of cities, might offer new prototypes for sustainable, fulfilling life—only if we are keen to see and invest in its potential.

As our cities swell to breaking, perhaps we are poised at a new threshold. The universal migration to the metropolis is no longer inevitable. “Countryside: A Place to Live, Not to Leave” does more than document change; it dares us to imagine a reversal—a future in which rurality is not exile but choice, heritage not a relic but a foundation. “The exhibition purposefully ignores the ‘West’ and shifts the perspective towards Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and China as new global positioning,” Ben Hur continues. “It is a manifesto aimed at reversing the tide of urban migration and offering a plausible future for the countryside as complementary to cities.” A paradigm is therefore reimagined, in which past and potential meet, and it is here, at this intersection, that the next chapters of human habitation may be written.

Rather than serving merely as an exhibition space, the school grounds remain an educational environment where old classrooms become active laboratories for research and exploration. “What sets this setting apart is its unprecedented fusion of education, agriculture, and technological experimentation, all woven together in the heart of the desert.” This hands-on approach enables participants not only to witness but also to actively contribute to the breakthroughs unfolding, highlighting the transformative power of collaborative innovation in a landscape shaped by both tradition and cutting-edge science. AMO successfully created a dynamic, ever-evolving platform for research on today’s crucial issues—and it must continuously integrate new academic findings and encourage active public participation for its ambitious mission to succeed in the long run.