Completed in 1959, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York is the last significant design by Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as one of his most famous works. It represents on many levels the conclusion of a decades-long research on organic architecture, that Wright started at the turn of the 20th century with the group of his “prairie houses”, and then evolved in the 1920s and the 1930s through such iconic buildings as the Kaufmann House in Bear Run, Pennsylvania (1935-1939) and the Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin (1936-1943).

The partnership between Wright, philanthropist Solomon R. Guggenheim and curator Hilla von Rebay is established in 1943. At that time Guggenheim’s collection, mainly comprised of works from the European avant-gardes, and abstract art in particular, is displayed in the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, founded in 1939 on the initiative of Rebay and located in a generic Midtown Manhattan rented space. While the institution’s property rapidly increases, Guggenheim and Rebay turn to Wright, asking him to design an unconventional museum building, conceived specifically to establish a dialogue with the non-figurative art that it shall host. Rebay overtly states that she is looking for “a temple of spirit, a monument!”.

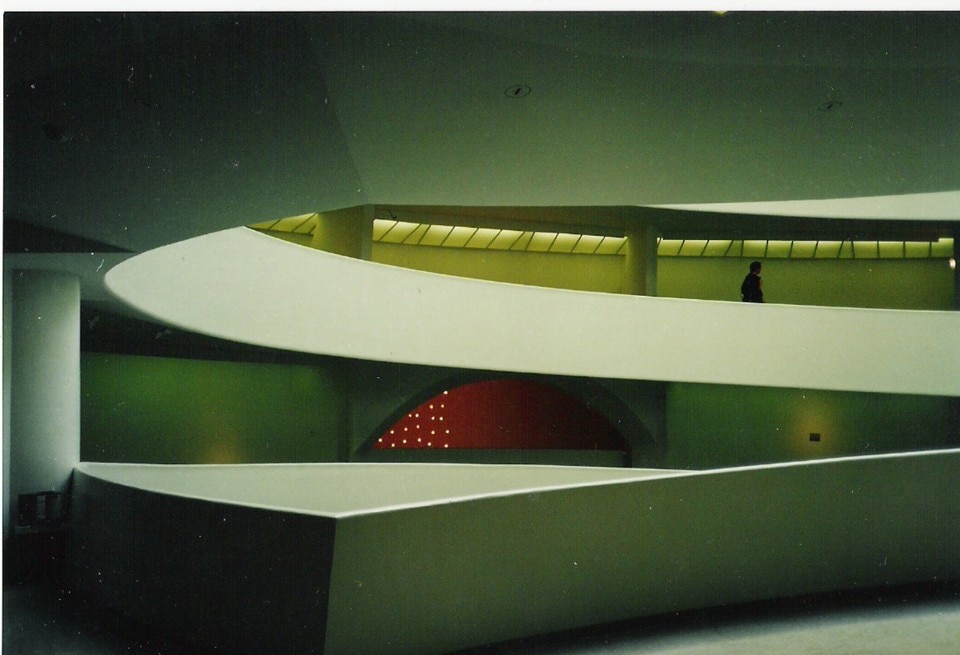

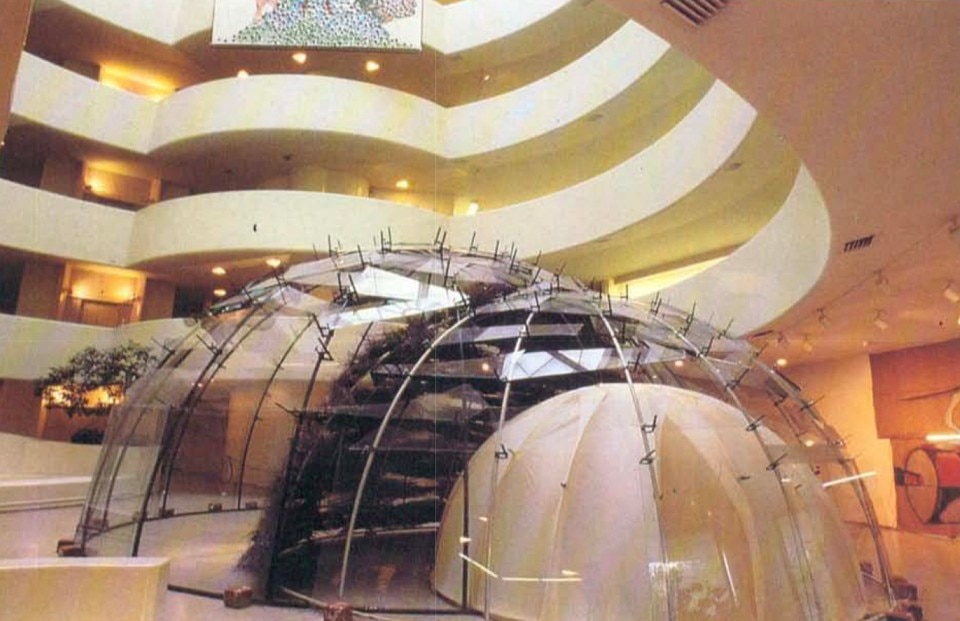

From this specific request stems the most surprising feature of the project. Wright distances himself from both the classic configuration of traditional beaux-arts inspired museums, laid out as the juxtaposition of enfilades of enclosed rooms, and the understated modernist “white boxes”. As opposed to both these solutions, he organizes the visit to the Guggenheim Museum as a single spiral ramp, sided by a sequence of alcoves and wrapped around a full-height atrium, lit up the natural zenithal light of a wide skylight. The whole exhibition path overlooks this giant order void, through which unexpected connections are established between displayed works. Visitors can look at them from multiple and ever changing vantage points, as they pace the “promenade architecturale” that leads them downwards, from the top to the ground floor of the atrium.

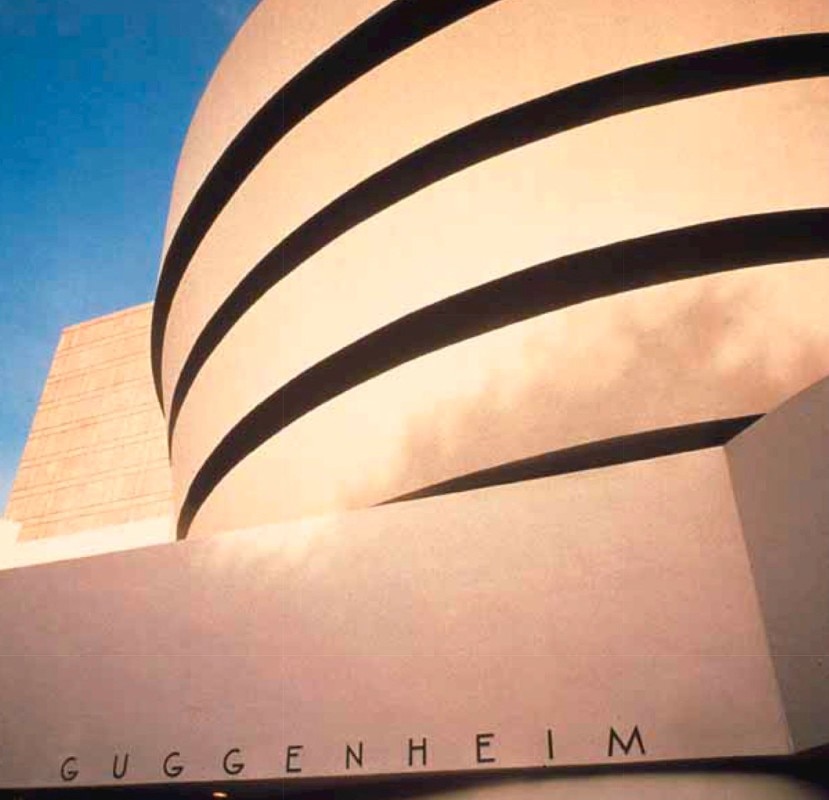

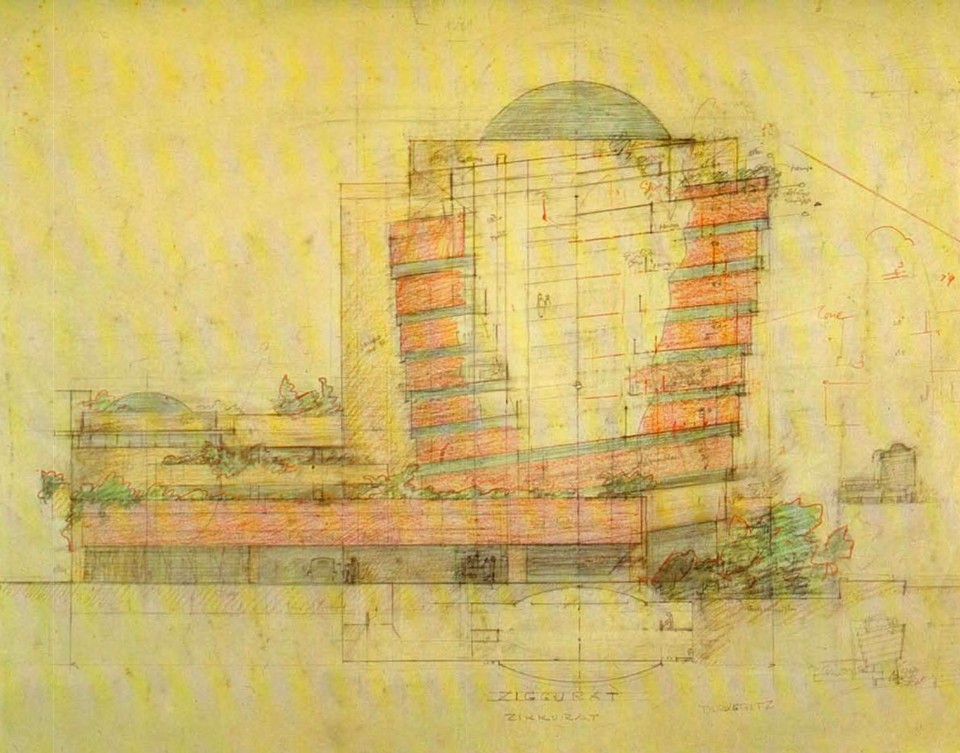

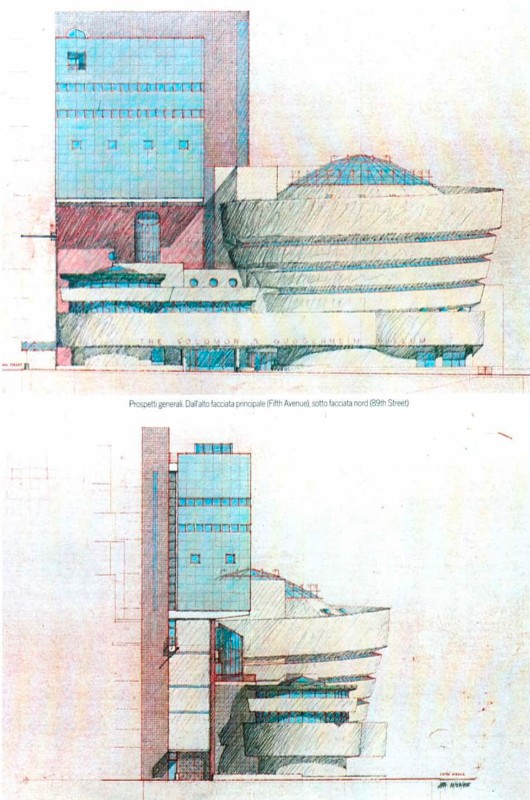

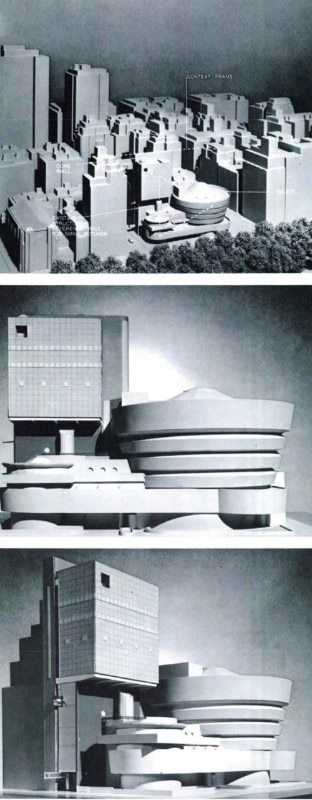

This distinctive geometry translates almost automatically on the Guggenheim Museum’s external volumes. Wright employs the word “taruggiz”, that is an inverted ziggurat, to define the upside-down truncated cone located on the corner between Fifth Avenue and 88th Street. A second cylinder adds to the “tarrugiz”, initially meant to host Guggenheim’s and Rebay’s apartments, and later converted in an additional exhibition space. The organic shapes of Wright’s work make it an evident exception within New York’s urban landscape, in particular as it integrates the uninterrupted row of tall buildings bordering Central Park on the Museum Mile section of Fifth Avenue.

Besides these iconic elements, the original proposal by Wright has been repeatedly altered. The red shade initially envisaged for the “taruggiz”, for instance, has never seen the light of day, similarly to a projected tall block, that would be eventually realized in the 1990s, according to an alternative design by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates. On that same occasion, in the frame of the interiors' global restoration and renovation, the atrium’s skylight would be reopened, several decades after its shuttering.

Over time, the Guggenheim Museum’s atypical features have attracted much criticism, mostly from professionals of the field. Already back in 1959, on the year of its inauguration, a few month after Wright’s passing, the Time published a letter of complaint signed by 21 artists, who refused to display their work within a shell that they deemed unsuitable for the purpose. Furthermore, several curators lamented the struggling to properly set up a faulty space, whose unevenness is due, amongst other factors, to its sloping floors, the concave shape of its alcoves, the limited roof heights, and the uncontrollable presence of natural light.

Regardless of this practical shortcomings, which resulted in countless anecdotes, today the Guggenhein Museum is universally recognized as a seminal work of 20th century architecture, and is now part both of the US National Historic Landmark (since 2008), and of the UNESCO World Heritage List (since 2019, alongside seven other buildings by Wright). With the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by Frank Gehry (1991-1997), the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and the upcoming Guggenheim Museum Abu Dhabi (also by Gehry, currently under construction and whose fate is still unknown), it is part of the Solomon R. Guggenheim’s museum network, amongst the most relevant in the world for the size and quality of its collections, as well as in terms of number of visitors.